This Week in China’s History: December 5, 1978

“What is true democracy? It is when the people, acting on their own will, have the right to choose representatives to manage affairs on the people’s behalf and in accordance with their will and interests of the people. This alone can be called democracy. Furthermore, the people must have the power to replace these representatives at any time in order to prevent them from abusing their powers to oppress the people.”

A paragraph from the Declaration of Independence? A commentary on the state of American politics in the wake of the Trump presidency? Neither. This is an excerpt from an essay by Wèi Jīngshēng 魏京生, titled “The Fifth Modernization,” posted on Beijing’s “Democracy Wall” in the early hours of December 5, 1978. (This translation is from Kristina Torgeson in a book of Wei’s writings, The Courage to Stand Alone: Letters from Prison and Other Writings.)

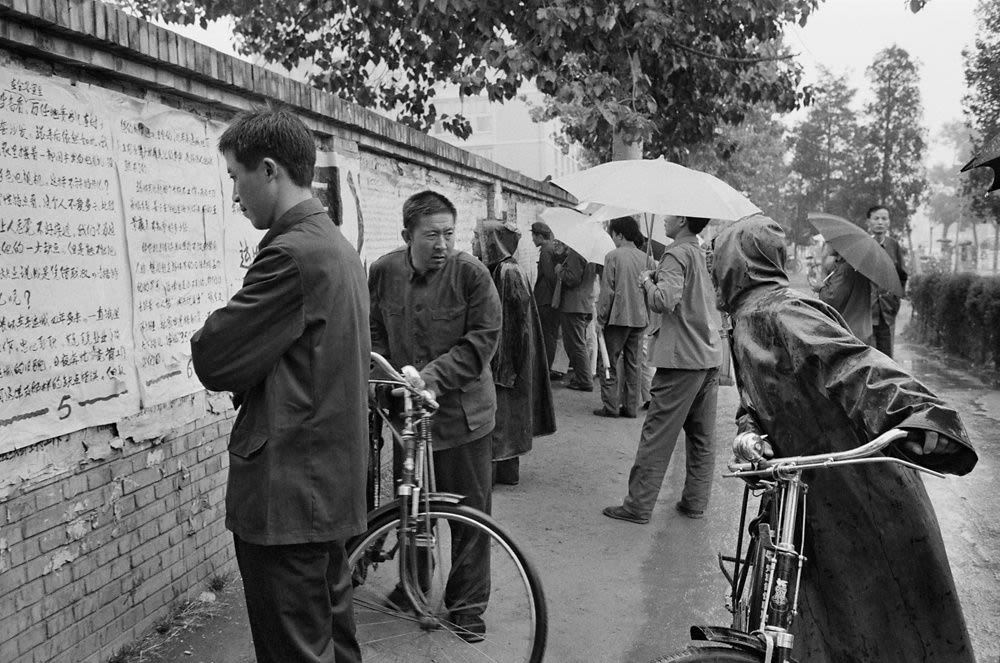

Democracy Wall was in the neighborhood of Xidan, just west of Tiananmen Square along Chang’an Avenue. Walls in public places had long been spots for posting notices and spreading news in China, and before television (never mind the internet) people would assemble in city or town centers to gather news and announcements. The Kangxi emperor had his Sacred Edict posted across the Qing empire in this way; more recently, newspapers would be posted in their entirety at city intersections (in the 1990s, I would trek each week to the center of town in hopes of seeing the China Daily with the latest scores from American baseball and football.) The wall at Xidan was part of this tradition, and it was one of the most prominent in China — a 12-foot-high, 200-yard-long gray brick wall at an important transportation hub near the center of the capital.

The wall at Xidan had been festooned with Cultural Revolution posters: propaganda art, criticism of “rightists,” and revolutionary slogans. When the Cultural Revolution ended, the wall filled with denunciations of the Gang of Four and praise for Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平, as Ezra Vogel described it in his biography of Deng. And in late November 1978, copies of a Communist Party Youth League journal went up, including articles demanding that the verdict of the April 1976 “Tiananmen Incident” be reversed.

The Tiananmen Incident had been the violent suppression of demonstrators mourning Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来, which Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 had deemed to be veiled criticism of his own rule. The Party did in fact reverse that verdict on November 21, 1978. Emboldened by the government’s willingness to change its mind and, apparently, accept criticism, more posters appeared on the wall. Some went beyond criticizing the Gang of Four to questioning even Mao himself.

As Vogel wrote, “After the decade of the Cultural Revolution, when information had been tightly controlled, many people were simply curious. Others [knew] that in the past any ‘incorrect’ view might lead to punishment….There was a buzz of excitement around Xidan Wall as new postings continued to appear.”

The end of the Cultural Revolution left the Party with several possible paths forward, each with pitfalls. Many who were now in or vying for leadership positions had suffered grievously from the Cultural Revolution; some of them wanted revenge, or justice (or both), but doing so would risk a renewed cycle of violence and persecution, just with different victims. Others saw the Cultural Revolution as a brutal denial of freedoms, and wanted to give the people greater opportunity for expression and autonomy. Still others wanted to restore the routine workings of the state, which had been undermined by extremes of ideology. And what about Mao’s cult of personality, which had been the linchpin for the entire movement? Needless to say, all these views, and others, overlapped and interacted with one another.

Democracy Wall challenged the Party on all these fronts. For Deng Xiaoping, now maneuvering into power, the central tension was between, on one hand, the wall providing a safety valve to prevent grievances from escalating, and on the other, the wall platforming criticism that could undermine the state as it tried to regain control. In Vogel’s words, “How much could the boundaries of freedom be expanded without risking that Chinese society would devolve into chaos, as it had before 1949 and during the Cultural Revolution?”

What limits there were on free expression at the wall were never explicitly stated, and they were difficult to discern. Deng reportedly endorsed the Wall — it had, after all, begun with statements of support for him against the Gang of Four. On November 26, Deng rhetorically asked a visiting Japanese politician, “What is wrong with allowing people to express their views?” and supported “the masses for promoting democracy and putting up big character posters.” People flocked to the wall, many of them lamenting or seeking redress for suffering during the Cultural Revolution. Were criticisms of the Cultural Revolution supporting the Communist Party, which had turned its back on the extremism of the 1960s, or were they attacking the Party, which in any event had also been in power during not only the Cultural Revolution, but also the Great Leap Forward and the Anti-Rightist campaign? Lines were blurry; limits were vague.

Those limits came into clearer focus around 2 a.m. on December 5, when friends and supporters posted Wei Jingsheng’s lengthy (running more than 4,000 words in English translation) essay.

The essay’s title draws on the “four modernizations” that Zhou Enlai had promoted a decade earlier. To advance, China needed to modernize its agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology. First articulated in the 1960s, the four modernizations had been central to Zhou’s vision for China until the end of his life, and would become a key part of Deng Xiaoping’s policies. But even as Deng prepared to make the four modernizations formal policy — he would enshrine them at the Party plenum later in December — Wei took them to task as inadequate, arguing that China could only be truly modern if a fifth reform were to take place: democracy.

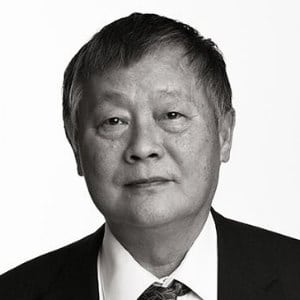

Wei Jingsheng grew up in a family that was just a cut below the Party elite. Both of his parents were Party members, working in the middle management of the People’s Republic. Just graduated from the High School Affiliated with People’s University, Wei became a Red Guard in 1966, at the height of the turmoil. He then joined the military, serving at times to protect grain stores and other infrastructure from attack by various political factions. Discharged from the army in 1973, Wei was assigned to work as an electrician at the Beijing Zoo.

His experience during the Cultural Revolution disillusioned him about the Party’s leadership: the extremes of poverty, autocratic policies, and racial discrimination (Wei was particularly influenced by the sufferings of his Tibetan girlfriend’s family) suggested to him that the promises of 1949 had not been realized. “Do the people have democracy now?” he wrote in “The Fifth Modernization.” “No! Don’t the people want to be the masters of their own destiny? Of course they do! That is precisely why the Communist Party defeated the Nationalists. But what became of all their promises once victory was achieved?”

“The answer is obvious,” he declared bluntly. “The Chinese people should not have followed the path they did.”

For Deng, the Democracy Wall was helpful when he was working to take power; once he was in power, it became something different. Certainly when posters stated, in so many words, that Communist Party rule was a bad idea, a line was being crossed, but Wei Jingsheng went even further: On March 25, Wei posted another essay on the wall, this one declaring with no uncertainty, “Does Deng Xiaoping want democracy? No, he does not.”

Three days later, on March 28, the Beijing city government banned “slogans, posters, books, magazines, photographs, and other materials that oppose socialism, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the leadership of the Communist Party, Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong thought.” The following day, Wei was arrested, along with an estimated hundred other activists.

Wei was held in solitary confinement until his trial in October, where he was convicted of being a “counterrevolutionary.” His sentence was unexpectedly severe — 15 years — in part, it is believed, because he refused to plead guilty. He was released nine days before the International Olympic Committee would decide on Beijing’s (as it would turn out, unsuccessful) bid for the 2000 Olympics.

Wei was arrested again in 1994, this time for his work with survivors of the 1989 protests. Sentenced to 14 years, he was released because of ill health and allowed to travel to the United States, where he still lives.

In the decades since Democracy Wall, there have been many dissident moments in China: 1989, of course, but also the Shanghai student protests of 1986, Liú Xiǎobō 刘晓波 and Charter ’08, the Umbrella Movement of 2014, and others. Many of these movements have an (often unrecognized) forebear in Wei Jingsheng and his call for a “fifth modernization.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.