Chinese soccer 2021: A postmortem

When the next World Cup rolls around — in Qatar next autumn — China will once again be missing. That in itself isn’t shocking, considering China has appeared in only one World Cup and is more accustomed to ignominy during the qualifying process. But what ails Chinese football currently runs much deeper.

The Chinese Super League (CSL) resumed on Sunday. For the first time, a CSL season will fail to finish in the same calendar year, as this season began in April nearly two months late (for mysterious reasons), then shut down for four months to accommodate the national team’s World Cup qualifying campaign. The league’s return was not greeted with fanfare: literally, in one sense, as there were no fans in Guangzhou, Suzhou, Kunshan, or Jiangyin, the four cities hosting CSL games within bubbles; and figuratively, considering the financial woes of many of the clubs.

In China, the top domestic soccer league is a sideshow in China’s grand football plan — and indicative of one of the biggest reasons for the country’s decades of footballing under-achievement.

Normally, the league campaign would have concluded over a month ago. But these are not normal times. Chinese football is a mess. When the season started, the league was missing its reigning champions, Jiangsu Suning, which went bankrupt following its parent company’s decision to focus investment in Italian football with its Inter Milan stake. Serious doubts exist over the future of several other clubs, including China’s most successful, Guangzhou FC, which hasn’t paid its players for months. The debt crisis of its parent company, Evergrande, has cruelly exposed the fragile nature of corporate involvement in Chinese football. Guangzhou FC’s new stadium sits half-finished on the outskirts of the city, with no one knowing whether the facility will ever be done, or if it is, when fans will be able to use it for its intended purpose; there have been no fans in home stadiums for over two years due to COVID restrictions, which don’t look like they’re ending anytime soon.

And what was up with that four-month break? The Chinese Football Association (CFA) had decided the league would take a COVID-related hiatus to help the national team, since World Cup qualifying games were scheduled from September to November. Because of China’s strict quarantine rules, it was impractical for national team players to travel from Dubai, where it was playing its qualifiers, back to China for league matches. Predictably, the hiatus turned out to be a futile exercise — China is effectively out of the World Cup barely halfway through the final round.

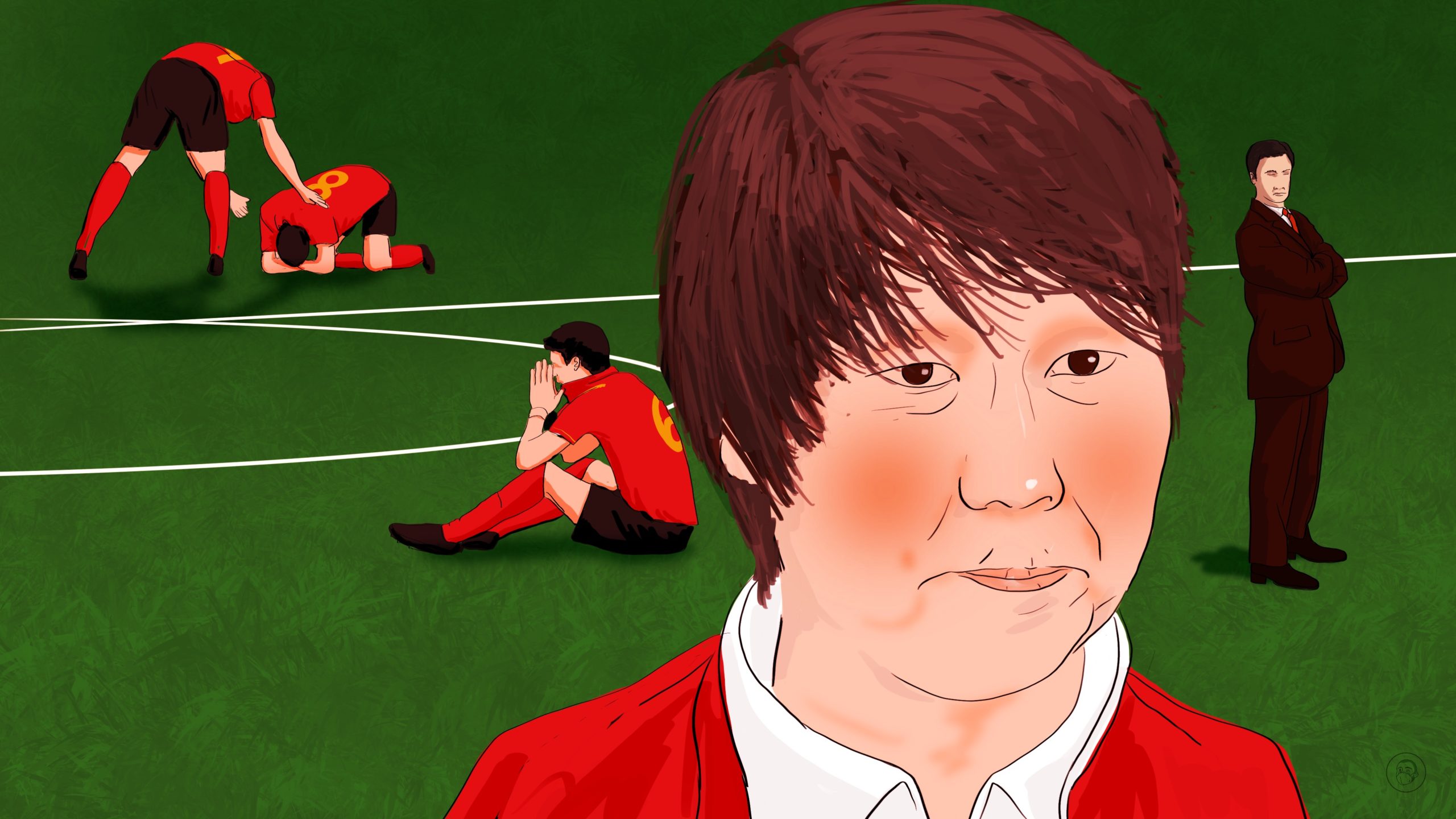

This resulted in another depressing development: Lǐ Tiě 李铁, a modern and progressive head coach once lauded as the man to finally lift Chinese football, was sacked for failing where nearly every coach before him has also failed: to get China to the World Cup. (The team’s lone appearance, in 2002, feels more like a fluke with each passing four-year cycle.) This was despite Li swooping in halfway through the campaign, taking over for Marcello Lippi in November 2019, and turning the team’s performances around to secure a final-round qualifying spot to face the likes of Japan, Australia, and Saudi Arabia.

Fans made the usual complaints over tactics and player selection. But the hard truth is that, even with naturalized Brazilians such as Elkeson (艾克森 Ài Kèsēn) and Alan Carvalho (阿兰 Ā Lán), China just isn’t good enough to finish ahead of the continent’s best sides. Unfortunately for Li, this glaringly obvious fact was lost on the media and the CFA. He also upset the establishment by making the sensible observation that having to live on the road for months made it much tougher for his squad. Li, who has a reputation of being outspoken and unafraid to criticize his superiors — always a recipe for trouble in China — became the subject of rumors in the Chinese football press. It was reported that he allegedly indulged in some kind of “financial irregularities” surrounding player transfers while coaching at Wuhan Zall a few years back — though making such allegations about a football coach in China, to paraphrase the movie Apocalypse Now, is like “giving out speeding tickets at the Indy 500.” It’s possible this was part of a smear campaign to discredit Li for fear of what he might say in the wake of his departure. But power politics is just another familiar thorn in the side of the game here.

One of the least-recognized failures of Chinese soccer — among its many — is the way the CFA treats the CSL like a vassal at the service of the country’s soccer brand.

Looking ahead, the outlook for the 2022 season is troubling. All told, over the last three seasons, upwards of 15 Chinese clubs across all three league divisions, including storied teams such as Korean ethnic outfit Yanbian and former Asian champions Liaoning, have ceased to exist. The sorts of questions hanging over the league are existential in nature: Which clubs will still be around? When will the league start? What format will it take? Which foreign players will still be in China? Who will leave because they still haven’t been paid?

It also looks likely the CSL will endure a third season of having no fans in home stadiums. Setting aside how well China has handled COVID in society at large, there is no sports league in the world that can sustain three years of empty stadiums and expect its clubs to escape unscathed. Millions of people cram onto public transport in China every day without COVID being an issue; why are people still not allowed to gather at outdoor venues to watch soccer?

The league, the clubs, the support base. These are what drive football anywhere and what ultimately deliver successful national teams. So what’s different in China? Damningly, a Soviet sports mentality persists in the form of the Chinese FA’s tunnel vision on the national team, to the detriment of all else. And while some recent problems can be attributed to the pandemic, what COVID really has done to Chinese football is simply what it has done elsewhere: brought into sharp focus deep-rooted problems.

In normal times, the CSL is forced to take weeks-long breaks whenever the national team plays, leaving the vast majority of China’s professional footballers with no competitive games for extended periods. A 2018 national training camp took around two dozen players on the fringes of the national team away from their clubs, just as the league was entering its most crucial phase, to do military training exercises, making a mockery of competitive integrity. There have also been questionable player movements — Guangzhou FC has long been suspected of using opaque methods to sign most of China’s best players to create a de facto national team. This allegedly happens at the behest of the CFA, which somehow overlooks simple problems such as the national squad being an ever-changing group of players anyway, and the question of who would dare try to defeat the national team in this most nationalistic of countries. The CFA has also tried to put a development team in the league on an official basis, only to meet resistance from more enlightened voices pointing out that no one else does this because it compromises the sporting integrity, image, and commercial viability of the league.

There are also other issues that undermine the standing of the league in general, such as scheduling matches during strange hours when most people are at work, which suggests the competition is not really worth watching for all but a minority of hardcore enthusiasts.

One of the least-recognized failures of Chinese soccer — among its many — is the way the CFA treats the CSL like a vassal at the service of the country’s soccer brand. Most of what you will read about Chinese football, in English at least, focuses on the failures of the national team, or looks at the game through an economic or political lens. For example, discussing Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 supposed love for the game and how big business rides on his coattails, lavishing astronomical sums of money on the sport, trying to curry political favor by helping China find 11 guys who can do a decent job of kicking a ball around. These are valid perspectives. They focus on the top, which is how most things in China are understood. But China’s top-down nature is precisely why it has had little success in its football project.

If we take a look at the fundamental nature of the sport, we can see why domestic leagues are given priority in successful football countries. Football’s essence is based on its simplicity, ease of play, and as a result, its strong connection to the communities in which it is played. In other words, it is a sport that grows from the bottom up. It is a game that is essentially a product of civil society — something most commentators agree is in serious decline in modern China. In a similar way, football’s governance and focus just reflects the centralization of power in China in general.

The influence of politics and business is far from absent in the game’s heartlands in Europe and South America, where corporations have long since taken over and run the sport. But it is still ultimately reliant upon a massive network of individuals, clubs, groups, and societies, both formal and informal, filled with people who play the game and support it at its most foundational level. A myriad of youth and amateur leagues, plus thousands of free-form casual games played for fun wherever and whenever people can find the time and space, are the lifeblood of the sport. Football games in general work in tandem with the fan culture of watching matches to create a spectacle to entice others to experience. These networks form the basis of football culture.

They also form the foundation of what are known as football pyramids — hierarchical competition structures formed by a broad base of small local clubs in regional leagues watched by a handful of spectators, to a narrow range of larger clubs from bigger towns in nationwide leagues, to a small group of big clubs in the top division that may even enjoy global followings. In all successful football countries, such a system plays a vital role in sustaining the sport, offering not only entertainment, but also a sense of belonging and identity for many of those who follow clubs, and a means to express civic pride. The key point is that, for most kids growing up, they most likely dream of one day playing for their local club, or a big club in their country. And if they fall short, in a football country they will have no shortage of other clubs more suited to their level, and still make football a viable career choice. A kid growing up in the UK may not live his dream of playing in front of 70,000 at Old Trafford, but he could still have a great career turing out in front of 20,000 each week at a second-tier club, or even a very rewarding one as a hero at a small club in the lower rungs playing in front of 5,000 or less rabid hardcore fans in a random town. In China? They are lucky if there are even a dozen professional clubs with either the money to pay wages or the fanbase to offer some glory or adulation.

Few Chinese players have the talent or desire to move overseas, so for them, the odds of making a decent living from football are tiny. In today’s hyper-competitive society, it’s no surprise football is seen as a questionable career choice by most Chinese parents. There are perhaps hundreds of soccer stars in China who never get a chance to develop. A prestigious league system afforded the proper pride of place in China would go some way to giving potential footballers more plentiful and realistic options, as well as a more assured way of capturing the attention of the nation; the national team certainly isn’t succeeding on this count, considering it rarely wins meaningful games and doesn’t often play anyway.

If much of Chinese football’s current predicament sounds negative, there is still one shining positive: Chinese fans. To describe them as “long-suffering” does not do justice to the fact that some, at China’s oldest clubs, are now in their fourth decade of supporting their teams through thick and thin. Such dedication is one of the few areas where Chinese football stands as an equal, at least, compared with traditional football regions. Such supporters are the lifeblood of the Chinese game. They are crucial in popularizing the sport and creating a very visual and audible message that Chinese football is something worth getting into. With all the doom, gloom, and uncertainty surrounding the game, Chinese football really needs to focus on making use of what little it has going for it.

But fans were once again absent this weekend. Some local supporters are looking enviously at images of packed European stadiums in countries where COVID is now just a fact of life and wondering why, in a country with hardly any COVID, attending games isn’t possible. In the near future, allowing supporters to return to their beloved home stadiums in at least some form isn’t asking for too much. But when the 2022 season begins sometime next spring, the damage of a third year of isolation may see China’s football league further alienate the country’s last remaining true football fans. The question is: Will the CFA actually care?

See also: A China Sports Insider podcast interview with Nikki Wang, formerly with Deloitte China as head of sports business where she advised the Chinese Super League, and Tariq Panja of The New York Times:

U.S. Olympic “boycott,” hockey showdown looming, and Chinese soccer with Tariq Panja and Nikki Wang