This Week in China’s History: December 16, 1627

An end to corruption, more than democracy, was the protesters’ target. And although they lacked a clear, systematic agenda, they insisted that they were the government’s conscience. In the words of one historian, they “used all their influence to have corrupt officials removed from their Peking posts.” According to another, “they voluntarily delivered themselves into the hands of murderers, and their blood made history.”

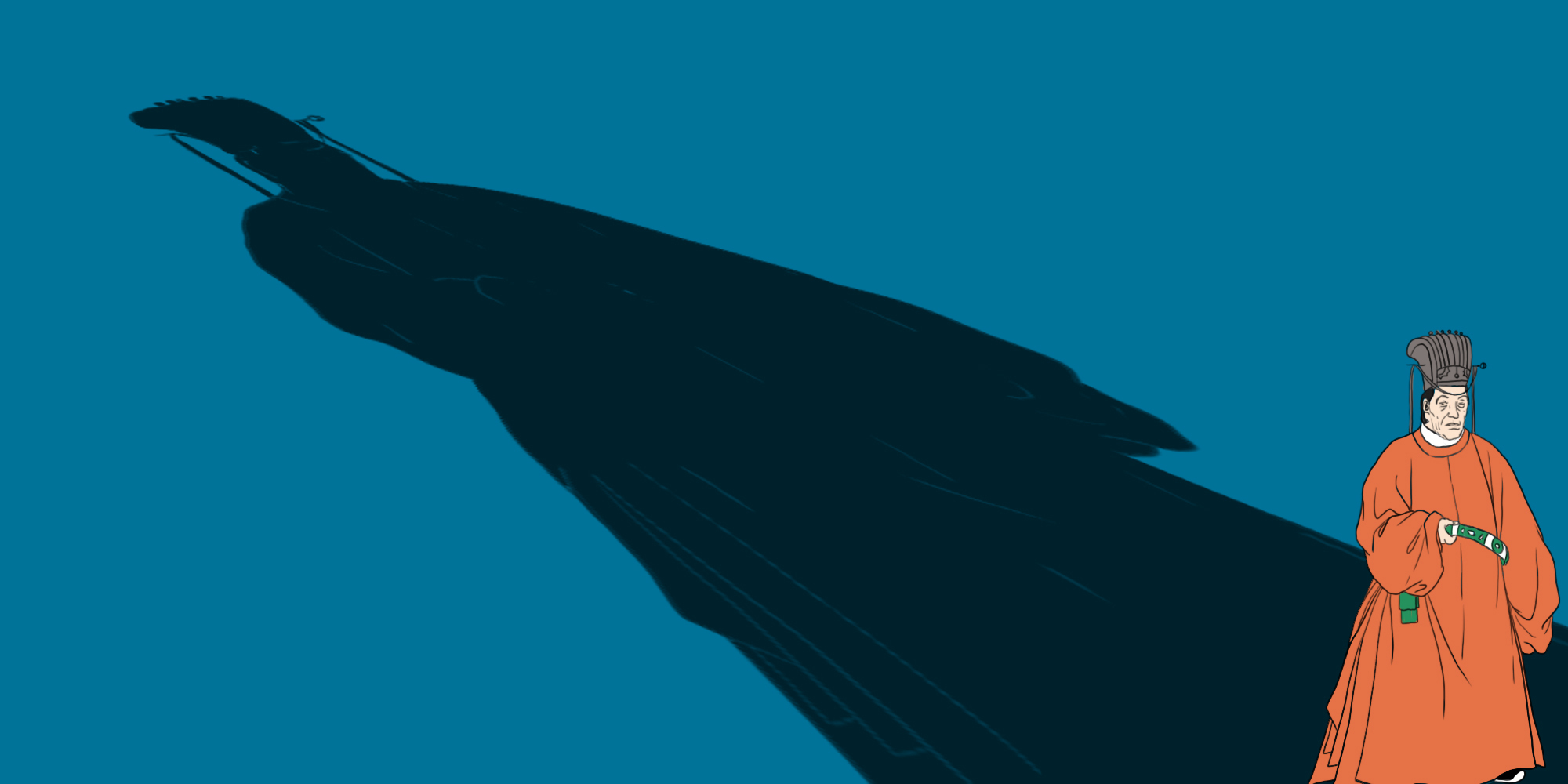

While this might clearly apply to the 1989 protests that centered on Tiananmen Square, neither Jonathan Spence, in the first quotation, nor John Dardess, in the second, are writing about 1989, or even the 20th century. They are describing the Donglin movement of the 17th century, a moral and political force that sought to change the fate of the Ming and, while they failed, found their official verdict reversed in a way that the protests of 1989 still await. It was on this week, in 1627, that the Donglin scholars were at last vindicated.

The Donglin Academy had Song dynasty roots, but it had been re-founded in 1604, in the Jiangsu city of Wuxi, a short distance west of Shanghai. Historian Tim Brook, in his history of the Yuan and Ming dynasties, presents the Donglin as an outgrowth of the governmental quagmire of the late Ming, especially the reign of the Wanli Emperor, generally seen as one of the least effective, least attentive, and least capable rulers in China’s history. As the emperor withdrew from political life, corruption at court increased, and the imperial household — eunuchs, empresses, and consorts — leveraged their power.

The Donglin Academy was a private institution, with some things in common with today’s think tanks, but also elements of a political party in that its goal was to influence government policy. Frustrated with the dynasty’s moral and practical failings, the men of the Donglin society met for public discussion on the issues of the day. Faced with inaction and decline at court, capable and interested men turned to the Donglin as an alternative path to government and politics. When the Wanli Emperor died, in 1620, the Donglin seemed poised for power. And once in power, they would insist on uncompromising virtue and unceasing moral exhortation. Few could meet their standards; compromise was a moral shortcoming.

The end of Wanli’s reign was viewed with great hope, but it ushered in an era of turmoil. His son and successor reigned for less than a month, dying after being prescribed red pills by an advisor to combat lingering diarrhea. In his place was enthroned the Tianqi Emperor, just 15 years old.

Besides his youth, two facts about the Tianqi Emperor became crucial. The first was that he showed little interest or ability in governing (Brook describes him memorably as “remarkably incompetent”). The second was that he was fiercely loyal to the eunuch Wèi Zhōngxián 魏忠贤 and consort Madame Ke (客氏 Kè Shì), who had cared for him as a young boy. Wei and Ke stepped into the power vacuum left by Tianqi’s indifference.

Alarmed by a return to an absentee emperor, Donglin scholars protested. Their attacks on Madame Ke and Wei Zhongxian — laced with sexism and self-righteousness, it must be observed — urged the emperor to rededicate himself to his realm, guided by Confucian values and diligence.

The Donglin officials, like censor Zhōu Zōngjiàn 周宗建, who accused the emperor of a quasi-incestuous attachment to his former wet nurse, overplayed their hand. Wei and Ke had the ear of the emperor and exploited his passivity to secure their power. Zhou Zongjian was arrested. For three weeks, he was tortured: “Finger presses applied to each hand, an ankle press on one leg, eighty blows with the big stick, and forty blows with the little stick,” Dardess writes in his book on the Donglin movement, Blood and History in China (the torture seems less quaint when recognizing that the “little stick” is akin to a 2×4, while the “big stick” resembled a bamboo 4×4). “Then,” Dardess goes on, Zhou “was taken to the ‘black room’ and killed by jailor Yanzi, either with a rock on his chest or a sandbag over his face, or perhaps both.” It was announced that he died “of illness.” Provincial officials collected outstanding debts from Zhou’s family.

Perhaps the most evocative arrest was that of Zhōu Shùnchāng 周順昌. Long an advocate of transparency and morality in government, he was held up as a paragon by students and officials in his hometown of Suzhou, where he was taken into custody in the spring of 1625. Suzhou residents surrounded police and pelted them with roof tiles and stones. At least one imperial policeman was killed. It took eight days to get Zhou out of Suzhou, so intense was the loyalty to Zhou Shunchang and the values of the Donglin society.

In all, 13 Donglin leaders met a similar fate. For three years, from 1625 to 1627, Wei Zhongxian orchestrated the killings, which used a combination of spectacle and mystery — the torture and murder was done in secret, but the victims were taken away in cages through public thoroughfares — to demonstrate his power. Many of the arrests were accompanied by outrage and protests, but Wei Zhongxian’s power was relentless. By 1627, he was effectively co-ruler. Edicts were issued in the name of both the emperor and the depot minister (Wei). Temples to Wei Zhongxian were erected in dozens of towns and villages. A victory over the encroaching Manchus was credited to Wei’s influence. The imperial college — students whose classmates had embraced the Donglin movement — petitioned to build a shrine to Wei Zhongxian that would parallel the Confucian temple where offerings were made.

With Wei Zhongxian unchallenged, the Donglin movement was declared “villainous”: “a deviant clique” and an “evil wind.” Wei was not old — approaching 60 — and moreover, his enabler, Tianqi, was just 21. There was no telling how long this reign would last.

Not long, as it happened.

In September 1627, the Tianqi Emperor died, abruptly. Although there was widespread speculation that Wei would try to seize power himself, no coup was attempted. Tianqi’s brother, who would reign as the Chongzhen Emperor, came to the throne. And with Tianqi gone, those who had suffered under Wei’s rule began to emerge. Within weeks, hundreds of petitions, memorials, and essays flooded the palace, documenting Wei Zhongxian’s corruption and licentiousness. On December 8, the Chongzhen Emperor impeached Wei and ordered him into exile. There was little doubt that his execution was delayed only a little until the Tianqi Emperor could be entombed, out of respect for the patron.

Traveling south into exile in his home, Wei Zhongxian and his entourage stopped for the night in a small town in Hebei. That night, he was found hanged by his own belt, dead by his own hand less than a year after being the most powerful person in China. The Donglin officials who had suffered emerged to restore to the dynasty its sense of purpose. Their final vindication came in March, when Wei’s corpse was exhumed to be ritually executed by slicing.

But the ending is not quite that. Wei’s suicide foreshadowed the Chongzhen Emperor’s own fate, 17 years later. For all their principle and virtue, the Donglin faction offered few practical solutions to the empire’s troubles. Historian Dardess notes that most observers felt that the Donglin society had made a terrible mistake by politicizing virtue, and sums it up this way: “What the Donglin had stood for and what it had suffered called for everlasting commemoration. And yet, at the very same time, what hindsight suggested the Donglin had done was to set in motion the collapse of the very dynasty they had thought they were rescuing, and for this it appeared they deserved resolute condemnation.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.