As American universities reevaluate the role of Western classical education, Latin and Greek courses are proliferating in China, where students see the Classics as a wellspring of wisdom that remains relevant regardless of hemisphere.

A block east of Tiananmen Square, in a classroom last July, Chinese school children were singing the nursery rhyme “Old McDonald Had a Farm” in Latin: “Donatus est agricola, Eia, Eia, Oh!” The students, aged 11 to 17, were taking an introductory Latin class with Leopold Leeb, a professor of literature at the prestigious Renmin University.

Every weekday during the summer, from nine a.m. to noon, Leeb holds a public class in a marble white church just a stone’s throw away from Beijing’s central government. On the day I attended, Leeb had given each student a Roman name. There was a Gaius, a Flavius, a Monica, and two sisters, Amata and Augusta. The sisters came from Changping, a two-and-a-half-hour train ride away. They sat in the front row and took naps during the 10-minute breaks.

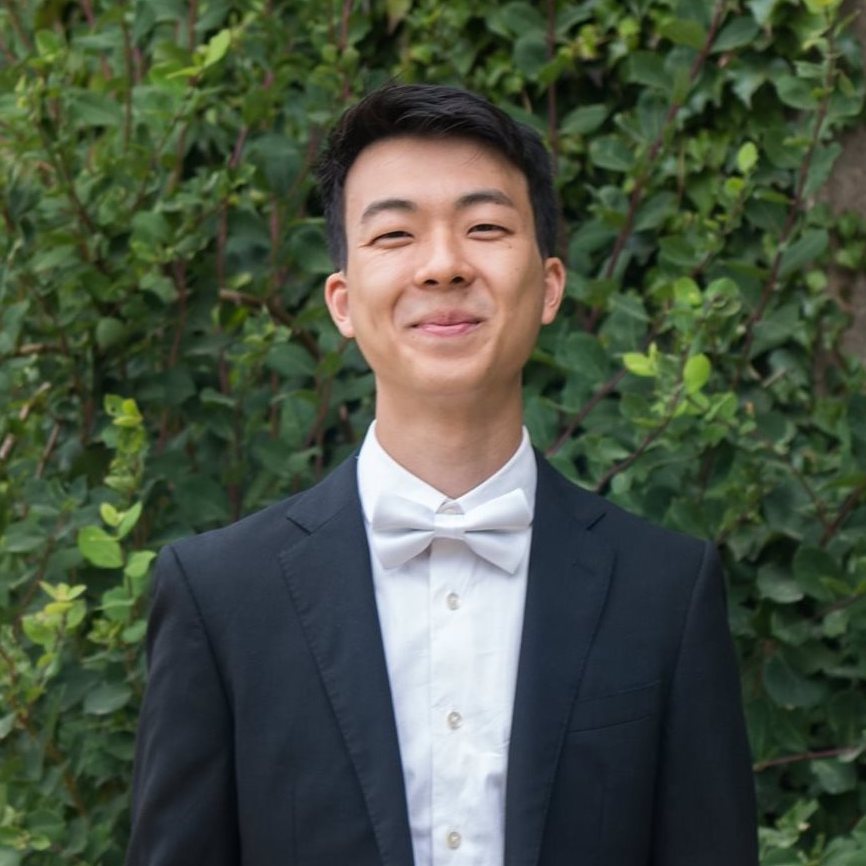

In the halls of China’s elite universities, Leopold Leeb is sometimes known as “the legendary Austrian.” His friends affectionately call him “Leizi” — Lei from his Chinese name Léi Lìbó 雷立柏, and zǐ (子) an ancient honorific reserved for esteemed Chinese intellectuals, as in Confucius (孔子 Kǒngzǐ), Mencius (孟子 Mèngzǐ), and Lao Tzu (老子 Lǎozǐ). For Leeb, a pioneer of Classics education (the study of Greco-Roman antiquity) in China, the sobriquet is apt: Leeb’s textbooks and dictionaries form a rite of passage for nearly all Chinese who wish to embark on Western Classical study. He has written several monographs on Greek and Roman history, 13 Classics dictionaries, nine textbooks, and over two dozen comparative works, giving Chinese readers access to Western ideas and texts. At 54 with no family and no hobbies, he displays an almost religious devotion to his work. “Obviously,” one colleague wrote of him recently, Leeb is “more concerned about China’s yesterday, today, and tomorrow than many Chinese.”

In the United States, the future of Classics education is on shaky ground. In 2019, the Society of Classical Studies held a conference in San Diego, titled “The Future of Classics,” that asked panelists to wax about “the diminution of our future role.” One panelist, Dan-el Padilla Peralta of Princeton, embraced that future, calling for a certain rosy, vaunted vision of the Classics to die “as swiftly as possible.” Peralta, who is Black, has become known in Classics circles as a searing critic of his own discipline — its lackluster representation of non-whites and its role in perpetuating harmful stereotypes. He once argued that “the production of whiteness” resided in “the very marrows of classics.” In May 2021, Peralta’s department at Princeton decided to remove the Latin and Greek requirement for its majors in a bid to welcome “new perspectives in the field.” Josh Billings, the department head, said that the decisions — which follow from Princeton’s initiatives to address systemic racism on campus — were given “new urgency” by the events following the death of George Floyd in May 2020.

At first blush, China looks like an improbable place to find “new perspectives” in the Classics. But in the past few decades, its universities have grown into bastions of curiosity about the West and its traditions. The irony is palpable. Across China, patriotic fervor is growing, and nationalists are more confident and dismissive of Western critics. But enter a humanities classroom and one is as likely to find students reciting speeches by Cicero as reading lines of Marx.

China’s Classics revival has its origins in the cultural renaissance of the reform era. In 1977, a year after Mao’s death, Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 reinstituted the gaokao, the entrance exam for higher education. “Suddenly, everyone around me was reading hungrily, joyfully,” recalled the writer Jianying Zha. “A torrent of foreign books poured out; classics were reprinted, new translations introduced, libraries packed, and long lines formed outside bookstores before each new publication.” The decision restored a sense of esteem to the pursuit of knowledge, an activity which was roundly punished during the Cultural Revolution. Having spent five of his formative years in France participating in the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, Deng knew the value of Western knowledge. His educational reforms included increased training for foreign languages. In addition, students were encouraged and offered resources to go abroad after studying at Chinese universities.

Reforms took hold gradually, then suddenly. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the most gifted students studied the sciences or were funneled into vocational training and sent out to the hinterlands to become teachers. But in 1999, the Communist Party made the strategic decision to expand higher education enrollment. The number of new college students increased by 47% the following year, and it has continued to soar ever since. From 2010 to 2013, the number of books released in China increased by 35%. By 2015, China had become the second-largest market for books behind the United States, a coming-out party for a new scholarly elite. “It’s a generational shift,” said T.H. Jiang, a philosophy lecturer in an elite U.S. university and a former humanities student at Peking University in the early 2000s. “Now, Chinese students are studying Medieval theology, the ancient Middle East, and ancient Near Eastern studies,” he told me. Jiang believed part of the intellectual curiosity came from a renewed confidence. “[Chinese students] started to think, ‘Oh, those other cultures are accessible to us. And because China is also a great civilization, why don’t we study other civilizations too?’”

Across China, patriotic fervor is growing, and nationalists are more confident and dismissive of Western critics. But enter a humanities classroom and one is as likely to find students reciting speeches by Cicero as reading lines of Marx.

The Communist Party had once actively encouraged the study of foreign civilizations. In the early years of reform, when it came to funding for the Classics, the Ministry of Education was as spendthrift as a Renaissance noble. It sponsored projects on Catullus, reprinted translations of Classical poets, and erected institutes dedicated to serious scholarship on Western civilizations. Bilingual editions of Greek and Roman texts began appearing in bookstores. (Translations of the complete works of Aristotle were completed in 1997.) Strong Classics faculty members began to proliferate throughout the country. The Chinese Journal of Classical Studies, established in 2010, produces scholarly work on ancient Rome and Greece. Since then, more than 250 Greek and Latin texts have been translated. Conferences are being held every year, and job postings for Latin teachers can be found in Nankai University in Tianjin, Fudan University in Shanghai, Southwest Normal University in Chongqing, Huazhong Normal University in Wuhan, among others. The Center for Western Classical Studies was established in 2011 at the prestigious Peking University, and, in 2017, Leeb’s Renmin University established its own Classics institute. “I could only ascribe it to magic,” observed a Chinese Latin professor, “that all of a sudden we came to have our own organization and the attention of the whole nation.”

After Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 rise to power in 2012, the world began to see China as a space for political rollbacks and regression. But Classics in China is still growing. The pre-eminent classicist Gān Yáng 甘阳 remarked in an essay recently that the term “classical studies” — gǔdiǎn xué 古典学 — had become such a buzzword of late that even “Confucian classics,” or jīngxué 经学, has been resuscitated from its century-long exile among intellectuals. Leeb says that the field is allowed to breathe because there is no such thing as a definitive interpretation of Classical texts. “It’s an element that protects the Classics,” he said. “They’re not so obviously anti-Marxist or anti-somebody.” Leeb also pointed out the problem of accessibility. “Classical Greek may never be popular in China because it’s simply quite difficult to learn. That kind of protects these studies too.”

In China, the Classics does not yet have its own department. Leeb, for his part, is affiliated with Renmin University’s School of Liberal Arts. But recently, prominent Classics scholars have tried to change this. Gan has described the absence of a Classics department as a “profound problem,” advocating for a unified academic home for both Western and Chinese Classical study. “I have said many times that modern Chinese universities lack civilizational roots,” he said in an interview in 2020. “A university without its own roots cannot be a great university, it can only be subordinate to others.”

Leeb’s skill as a cultural mediator between East and West, along with his Catholic faith, calls to mind China’s first Christian “zi”: the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci. In 1583, Ricci arrived in China with the dream of building a Sino-Christian Mission. In a few years, he had become so immersed in the culture that he confessed, in a letter to his college friend, “I have become a Chinaman.” His knowledge of Chinese language and culture reached something “no Westerner had ever come near to attaining,” observes the late sinologist Jonathan Spence. He left behind scores of Western teachings, including a Chinese translation of Euclid’s Elements, as well as the first Latin translation of Confucius. For his extraordinary deeds, the literati gave him the honorable title of “zi.” They called him “Lizi” — “Li” from his Chinese name Lì Mǎdòu 利玛窦.

Leeb is a man of unassuming stature. Bald, mustachioed, with a capacious forehead and seraphic smile, he has the benevolent aura of the Catholic missionary he once was. Like Ricci, his Chinese is the stuff of legend, but passed through his hardened German palate, it retains the accent of a foreigner. Leeb himself no longer identifies as one. “When I’m in Austria, I’m a foreigner now, I have nothing in common with the people. Whereas in China” — here, he gestures outside the dumpling house we had stopped at for lunch — “I have so much in common with the people.”

When Leeb arrived in China in 1995, China’s Classics appetite had just been whetted. Latin classes were offered at universities, but they were used to train specialists in fields like zoology, botany, and medicine. After completing his postdoctoral work in 2004, Leeb was told that the best way to secure a job was to teach German, his mother tongue. Philosophy departments were growing, and German was in high demand as Chinese scholars devoured the works of Kant, Hegel, and Husserl. But Leeb didn’t want to help specialists specialize, so he took a leap of faith. He applied to three Beijing universities as a Latin teacher. Two got back to him with only part-time offers, not enough to secure a visa. Then he received an email from Renmin University’s literature department. “Yes, you can teach Latin,” it read, “but you have to teach ancient Greek too.” He accepted.

In its quest for reinvention, Princeton’s Classics department looked at the standards of entry and lowered it. Leopold Leeb is training a generation of Chinese who can unequivocally pass it.

By teaching a generation of Chinese to read and write Latin and ancient Greek, Leeb finds common cause with Princeton’s Classics educators. Both are trying to pry open the gates of a long-exclusive field. “A student who has not studied Latin or Greek but is proficient in, say, Danish literature would, I think, both pose interesting questions to classical texts and be able to do interesting research on the ways that classical texts have been read and discussed in Denmark,” Princeton department head Josh Billings told the Atlantic. Had he replaced Denmark with China, he would have sounded just like Leeb. In its quest for reinvention, Princeton’s Classics department looked at the standards of entry and lowered it. Leeb is training a generation of Chinese who can unequivocally pass it.

Leeb’s current and former students, now more than 2,000 strong, are part of a generation of Classics scholars studying and teaching in Chinese universities. Many of them, who studied overseas, are helping shape China’s universities in their bicultural image. “The chair of my department told me I’m the only Chinese graduate student in Classics since the founding of the university 160 years ago,” said Luó Xiāorán 罗逍然, one of Leeb’s former students, who completed his Ph.D. in Classics at the University of Washington last spring. Luo began teaching at the Chinese Academy of Arts in Hangzhou University last fall. “I’m going to be the first Classics major to teach there,” he told me two months before his posting.

Luo is bone-thin with wide, dazzled eyes. When I met him for coffee near his university, he wore circular metal-rimmed glasses and a mandarin-collared shirt, the consummate style of a 20th-century Chinese scholar. In many ways, Luo is precisely the kind of talent Billings hopes to attract and retain at Princeton: a non-white Classics scholar from a non-Western part of the world. Ironically, though, when I asked Luo about his thoughts on the diversity efforts in the Princeton Classics department, Luo was dismissive. “It’s absurd,” he said. “If you want to get well-trained, educated classicists, you should have the requirement in there.”

Despite the West’s efforts to retain such talents, Luo is returning to China. When I asked him why, Luo told me that American students were simply less interested in their own Classics than the Chinese. “There just aren’t as many curious students in the Classics in the U.S.,” he said. “I taught at the University of Washington for over six years. I tried all kinds of stuff to keep it engaging — they just didn’t care.” Last year, by contrast, he gave a lecture in Hangzhou to a crowd of Chinese on the character of the Cyclops in Greek mythology. “I could see sparks.”

Why do Chinese appreciate the Classics more than their Western counterparts? One explanation involves the ideological scorecard at the end of the Cold War. In the West, the 1990s was an era of liberal triumphalism. Communism and fascism had been left to the dustbins of history, the theory went, and all societies would, sooner or later, reach a model of universal agreement and capitalist prosperity. As the space for political dissent narrowed, and the false promise of total consensus reared its ugly head, students raised in the tradition wanted out. Critical views of liberalism flourished. From post-structuralism to critical race theory, the ensuing decades saw the very foundations of the Western canon fall back into a subject of contestation.

Meanwhile, in China, the 1990s had the opposite impact. As surrounding Communist nations collapsed or disintegrated, Chinese scholars had to go back to the drawing board. Traditions had been destroyed by revolution, and so everything was on the table. Ideas became a constructive enterprise rather than an instrument of disruption. The difference in philosophical outlook is still palpable today: while Americans scoff at their legacy villas — the lofty traditions that have come to feel ever more pretentious and stuffy with time — Chinese are still searching for a home.

By and large, China has always treated Western ideas with a mix of wonder and pragmatism. In 1898, when the scholar Yán Fù 严复 first translated the works of John Stuart Mill and Adam Smith, China had just lost the First Sino-Japanese War, and Enlightenment thinkers acted like a fertilizer for the nationalist protests centered on notions of democracy and science. In 1920, the first complete Chinese translations of Marx appeared. The next year, the Communist Party of China was founded on the idea that social revolution would free China of foreign powers. After Mao’s death in 1976, a third wave of translations erupted, eclipsing the prior two in magnitude. This time, the translations came from thinkers as diverse as Michel Foucault and Friedrich Hayek, and seemed less structured and agenda-driven. But by the mid-2000s, some Western thinkers began to gain more traction than others.

In 2008, Evan Osnos, writing in the the New Yorker, described a “new vein of conservatism” emerging among China’s youths inspired by what some called “Strauss Fever,” referring to the German classicist Leo Strauss. By the 2010s, Strauss, along with German legal theorist Carl Schmitt, had suddenly become a hot topic among Chinese intellectual circles. “No one will take you seriously if you have nothing to say about these two men and their ideas,” a Chinese journalist told the historian Mark Lilla in the New Republic in 2010. Both men were translated into Chinese by Liú Xiǎofēng 刘小枫, a bespectacled Christian philosopher and a colleague of Leeb’s at Renmin University. Liu is a philosopher, but his specialty is in the Greco-Roman Classics.

The Strauss obsession offers another window into China’s Classics revival. A central idea of the German philosopher’s work was the difference, in the Western canon, between the ancients and the moderns — two groups distinct in several critical ways, from the view of rationality to truth and politics. Strauss, who was partial to the former, had provided a language to articulate China’s own estrangement with its ancient past. China’s Straussian scholars are, in other words, involved in a rehabilitation of Chinese ancient thought through the guidance of a German-American philosopher. In the mission statement of The Chinese Journal of Classical Studies, founded by Liu, the editorial board draws the link concisely: “to restore the spirit of the traditional civilization of China,” scholars must “command a profound understanding of Western civilization.”

China’s Straussian scholars are involved in a rehabilitation of Chinese ancient thought through the guidance of a German-American philosopher. Some of the highest-ranking members of the Communist Party are proponents.

Among Strauss’s criticisms of the “moderns” was the idea that Enlightenment thinkers had become overly preoccupied by modern exigencies as to have a distorting effect on philosophical practice as conceived by the ancients. Under Liu, Strauss’s views began to coalesce into a censure of Western progressive politics, along with the Chinese humanities departments that had welcomed them with open arms. The Chinese humanities, Liu argued, looked too similar to their Western counterparts. China was confronting a crisis of identity born from increased integration with the West, and it was none other than Strauss who offered China an egress. “The main reason for introducing Strauss to China,” Liu wrote, was “to avoid the century-long fanaticism toward all kinds of modern Western discourses.” Feminism, critical race theory, intersectionality: these were not for Liu the signposts of moral progress, but more like road spikes to be avoided on China’s own path to modernity.

“The Straussians in China almost unanimously view ‘political correctness’ in the West as a ‘second Cultural Revolution,’” Jiang told me. If Leeb was teaching Chinese the equivalent of how to walk in the Classics, Liu was giving Chinese a purposeful gait. For those schooled in the Straussian approach to the Classics, the answer to China’s future looked more often the same: a culturally conservative path bereft of the West’s postmodern demons.

Some of the highest-ranking members of the Communist Party may have caught Strauss fever. When Wáng Hùníng 王沪宁, China’s chief political theorist and a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, visited the United States in 1988, he was drawn especially to America’s neoconservative thinkers, many of whom were former students of Leo Strauss. Wang saw this group as the last holdouts against a scourge of leftists hellbent on destroying the West’s traditional system of values. In his book America Against America, a memoir of his visits, Wang cited the works of Allan Bloom, Daniel Bell, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan to rail against a “younger generation ignorant of Western values.” “If the value system collapses, how can the social system be sustained?” he asked. “The rise of neoconservatism [in America] suggests that the concern has reached epic proportions.”

Wang flirted with neoconservatism throughout the 1990s, and as he climbed the ranks of the Communist Party, his clout may have thrown lighter fuel on the Strauss craze among Chinese academics. Today, the neoconservative ideas of cultural cohesion are only growing. Last year, the Communist Party passed education reforms to hire more gym teachers and to “cultivate masculinity” in schoolboys. Media broadcasters have been forced to pivot from shows that display “effeminate men” to those that promote “traditional Chinese culture.” Timothy Cheek, an intellectual historian at the University of British Columbia, told me the latest diktats amount to a “cultural turn” in China’s modernization, what he calls “Allan Bloom traditionalism with Chinese characteristics.”

In his book The Classical Tradition, the Renaissance scholar Anthony Grafton remarks on the impossible challenge of documenting how the Classics has shaped our world: “An exhaustive exposition of the ways in which the world has defined itself with regard to Greco-Roman antiquity would be nothing less than a comprehensive history of the world.” Though Leeb and Liu differ markedly in their approach to the Classics, they nevertheless held onto a similar premise: that the Western tradition has left an indelible mark on China, just as it has with the contemporary West. To study its contours is, for Leeb, a process of self-discovery; for Liu, it is a recipe to reverse course.

That the Classics is a shared inheritance is one of Leeb’s most enduring lessons. “Everyday life in China is now based on all these contracts like marriage,” Leeb told me. “That was created by the ancient Romans. Most Chinese people are not aware of that.” Even some Chinese words, he explained, like the word for cheese, lào 酪, had likely come from Latin (lac is milk). To study the Classics as a Chinese is to know thyself. “To have a profound answer to the value of Chinese culture and tradition,” Leeb said, “you have to put it into perspective with what there is in the West. This so-called Western superiority or Chinese superiority, what does it mean?” Leeb’s words also spoke to the present political moment.

During my last interviews with Leeb’s students, I asked Qú Xīnchàng 瞿欣畅, a sophomore philosophy major, what was the most important lesson he had learned from Leeb. To my surprise, his answer had nothing to do with history or geopolitics.

“Modesty,” he replied. I asked if he meant that the Classics was too difficult.

“That’s part of it. But the other is that Classical knowledge, at its essence, is a lesson in humility,” he said. “Perhaps it was after the Enlightenment that our pride kicked in.”

The reference — the particularities of which escaped Qu’s notice — captured, perfectly, the fruits of Leeb’s work. Across all my interviews of Leeb and his students, no one saw a Classical education as irrevocably “Western”; it was as if the Greeks and Romans were a heritage of global culture, a wellspring of wisdom that remains relevant to all moderns regardless of hemisphere. It was a potent and refreshing idea. In an era of culture wars and great power competition, where fault lines seem so impenetrable, the Chinese Classicists saw smoke and mirrors: the rift between East and West, after all, would have been nothing compared to the gulf between ancients and moderns.

“The political climate now is more anti-Western,” Luo admitted. “But culturally that isn’t the case. Culturally, we still love the West. Look at these cars! Look at these people, look at these outfits, and this place!” He pointed to the cafe we chose to sit in, one that looked like it had been parachuted in from downtown Portland. He continued: “This is the place we selected, and this is not Chinese.”

One day, in 1996, Leeb sat down for tea at the house of his doctoral advisor, the renowned Confucian scholar Tāng Yījiè 汤一介. “You know,” Tang told him, “the views of people from the East and West can enlighten each other.” He described it using four Chinese characters: 互相发明 hùxiàng fāmíng — mutual illumination. Leeb never forgot it. “It’s stayed in my mind throughout the years,” he told me. “That is why I teach Latin.”