Inside the Olympic bubble at Beijing 2022

Much has been made about the Beijing Olympics organizing committee setting up a “closed loop” for the Games. What’s it really like? Our reporter reports from inside, where shuttle schedules are unreliable and hotel rooms are too hot. (The internet isn’t censored, at least.)

The Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics don’t officially begin until Friday, but with most athletes, coaches, and international media arriving in recent days, it feels like the Games are finally here. It will be a unique situation this year, as you’ve probably heard, with Beijing setting up a closed-loop system to keep the Games as safe as possible during a global pandemic.

But what’s it really like living in the loop?

I entered it a few days ago as an accredited Olympics reporter. And let me tell you, it’s been an adventure.

Transportation to and within the loop

It took a taxi, a shuttle, a bullet train, and two buses to travel from my home in Beijing to Zhangjiakou about 110 miles to the northwest, where I will be based. I entered the closed loop at the Main Media Center in Beijing, where I had to activate my accreditation, and then hopped on a high-speed train, which takes you from the heart of the capital to the mountains in 50 minutes flat, instead of the three hours by car.

But where the bullet train was a sleek and ultra modern affair, the transportation situation in Zhangjiakou has been anything but. Although a small resort, Zhangjiakou has close to 30 venues, hotels, media centers, and other Olympic locations, all served by two dozen different shuttles, not necessarily in a logical manner, with multiple changes sometimes needed to get to your destination. Not a problem in itself, unless you have to wait 30 minutes in -19 C weather.

And while the venues are within the closed loop, the roads connecting them are not. Why? Who knows. So instead of walking the 200 meters from your hotel to the press center, you have to take a shuttle, which could mean a half-hour wait, followed by a 20-minute journey, instead of five minutes on foot. Case in point: the ski jumping venue is located right behind the Zhangjiakou Broadcast Center (ZBC). But rather than opening a door and stepping out directly, media will have to hop on a bus to go around.

Add to this a confusing jumble of bus letters and numbers, unclear destination names, no maps, and drivers who sometimes ask you to disembark and wait for the next bus for no reason, and the result is a rather messy transportation situation in the loop and many befuddled athletes and media.

To top it all off, after some light snowfall on Sunday evening, shuttles became stuck on the road to the Genting Snow Park: they had neither snow tires nor chains.

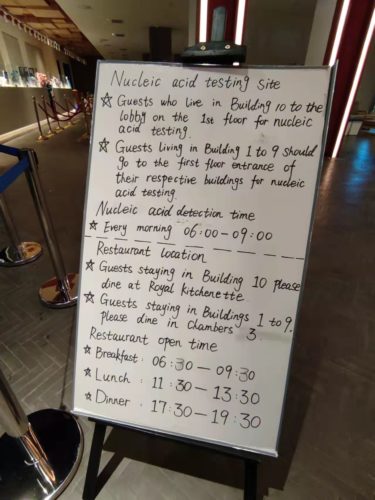

Daily tests and hazmat suits

COVID protocols had everyone worried in the lead-up to the Games. Playbooks published by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) clearly laid out the rules: anyone entering the closed loop needed to be fully vaccinated or spend 21 days in quarantine, have two negative nucleic tests in the 96 hours before arrival, and monitor their health for 14 days via an app. Between getting the timing right on the tests, especially for those flying in from abroad, and people testing positive every day, I know everyone was nervous over whether they would be allowed into the loop.

In the end, the process seems to have gone smoothly for most. A colleague arriving at Capital Airport was amazed to see staff in full-body protective gear, but said the system was slick and friendly.

A broadcast official noted that when he first arrived, people were confined to their workplace or their hotel room. Now, rules seem to have been relaxed, with people roaming around freely, meeting for meals or going out for a cigarette.

There have been complaints in some groups about anti-COVID measures in Zhangjiakou being excessive compared to Beijing, including the heavy use of chlorine as disinfectant. And there are plenty of people in hazmat suits walking around my hotel every day. A few days ago, I found one sitting outside somebody’s room on my floor. Possibly a guest who had tested positive? But we knew all of this going in. The question months ago was: would we be willing to put up with daily tests and quarantines for the chance to be at Beijing 2022? For true winter sports fans, the answer was a loud yes.

Accommodations

Extreme temperatures in the hotels seem to be keeping journalists in Zhangjiakou up at night. Not because it’s too cold. While outdoor temperatures have hovered around -15 C, room temperatures are almost tropical.

One reporter said the floor heating was so hot he could not walk around barefoot. Another proposed removing the card from the electricity slot at night to cool things down. Ironically, another journalist was later overheard at the hotel reception complaining that his room was frigid, as the cleaning staff had left the window open.

But let me tell you, the hot shower when I get back to the hotel feels like pure heaven after a day spent in the cold.

The rooms are new, simply furnished but practical and comfortable. What else do you need on a work assignment? WiFi is solid, and breakfast is included. Other food options are scattered between hotels and media centers, with prices varying widely.

And while we’re on the topic of internet, participants quickly noticed something unique about the Beijing2022 WiFi operating in much of the closed loop: it bypasses the Great Firewall, allowing anyone to access sites like Google, YouTube, or Twitter without VPNs. Hard to believe, but it’s true.

Apps galore

As per usual in China, there has been a heavy reliance on apps. But while easy and convenient when they work, apps become a nightmare when they don’t. The official My2022 app suffered serious technical issues two weeks ago, just as people needed to start tracking their health in the run-up to the Games. Not to mention reports of security flaws that meant sensitive information was vulnerable to hackers.

Anyone with Games accreditation can book bullet train tickets for free, using a different app. But if you can’t log in, you can’t get a ticket and can’t use the train, one of the easiest ways to reach Zhangjiakou (which will host the majority of the skiing and snowboarding events) or Yanqing (a suburb of Beijing that will host alpine skiing and sliding events).

There are special taxis that can be called using a Games Taxi app, but only for those with a Visa card — an official Olympic Games sponsor — or Union Pay app. That makes it tough for Chinese participants, who are more accustomed to using Alipay or WeChat for e-payments.

Friendly volunteers

Volunteers are a huge part of any Olympics, and Beijing 2022 is no different. Decked out in blue and white snow suits, they have been friendly and helpful, pointing people in the right direction, assisting with shuttle timetables, and if stumped for the English word, quick to whip out their phone and use their translation app — all with a big smile.

One volunteer stationed outside the ZBC explained he had entered the closed loop in early January and would only be able to go home in April — after the Paralympics in March and a further 21 days of quarantine. A university student from Hebei province, he will also have to make up for the classes he has missed, even if the month-long Spring Festival holiday will cover some of it.

“But it’s worth it,” for the experience and the opportunity of meeting people from all around the world, he said, gazing up in awe at the nearby ski jumping facility. The volunteers are housed in dorms of four, six, or eight, and for many, the work consists of standing outside in the cold for hours on end. But as far as I’m concerned, they’re already a highlight of these Games.

It’s only the first week

These are not my first Olympics, but COVID has made this an entirely different experience. Between strict protocols and other logistical problems, it’s telling that so many people I’ve spoken to who said they were mentally prepared to be sent home and not be able to cover these Games on the ground. There have just been so many variables this time around, so much that could go wrong.

That said, the week before the Olympics is always filled with negative headlines, criticism, and whingeing, as journalists look for stories to write before competitions start. At the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics, there was no snow. At Sochi 2014, media accommodations were a disaster. Athens in 2004 battled claims it would not be ready right up to the last minute.

The true test comes when the Games begin in earnest. This week, hopefully, problems will be ironed out, issues fixed, and processes further simplified. And once competitions get underway, hopefully the attention will be on the 2,900 athletes at these Games.