China in therapy: How families in crisis will affect China’s future

China’s tumultuous recent past has had profound effects on Chinese family life that are going to change the country’s future.

A 14-year-old girl, whom I’ll call Clover, was referred for therapy because she had formed a suicide club in her school, where her mother also taught. She was cutting on her arms, failing academically, and spending sleepless nights on her phone with classmates. Her mother also suffered acute “loss of face” because her fellow teachers all knew about Clover’s suicidal thoughts, while she did not. Clover’s maternal grandparents, who lived with the family, had both been teachers. They showered her with love, but also tutored her every afternoon and held high expectations for her academic performance at a school where all the kids were expected to go to a prestigious college like Peking University.

Clover’s situation exemplifies the way that school problems, depression, and suicidality have become epidemic for Chinese adolescents, who live under enormous pressure to perform, and who feel they are letting their parents down whenever they want to have a good time. Clover’s family members were loving, but they actually intensified the pressures that the Chinese academic system brings to so many teenagers.

A very different couple, whom I’ll call Dr. Hu and Mrs. Chen, sought marital counseling. Their differing expectations led to a marital crisis. Dr. Hu, 15 years older than his beautiful young wife, expected her to take care of him and their three-year-old daughter but not to make demands on him. Mrs. Chen, who was raised in the countryside, had her own business before marriage, and expected her much older husband to understand that child care was now her full-time job and that he should not ask her to do anything else.

Dr. Hu said that when he was six, his mother was sent to a Cultural Revolution reeducation camp, and he was sent with other separated children to raise themselves among countryside farm families. We asked him if that was hard on him.

No. It was a time of freedom, sunshine, and happiness. No one bothered us, and as children, we were all happy together. When I was 13, my mother was allowed to ask for me to live with her and her husband in Chengdu. I thought he was my father, but when I turned 20, my mother told me he was not. Even then she only mentioned it because my biological father had been rushed to the hospital, so she wanted me to meet him before it was too late. I had no interest in him.

Mrs. Chen had not suffered from the national traumas of the 1960s and 1970s, but she had grown up in a poor rural family. She was the favored youngest child, but poverty, her father’s abuse of her mother and siblings, and her desire to get out of the countryside to move to the city gave her markedly different expectations for marriage.

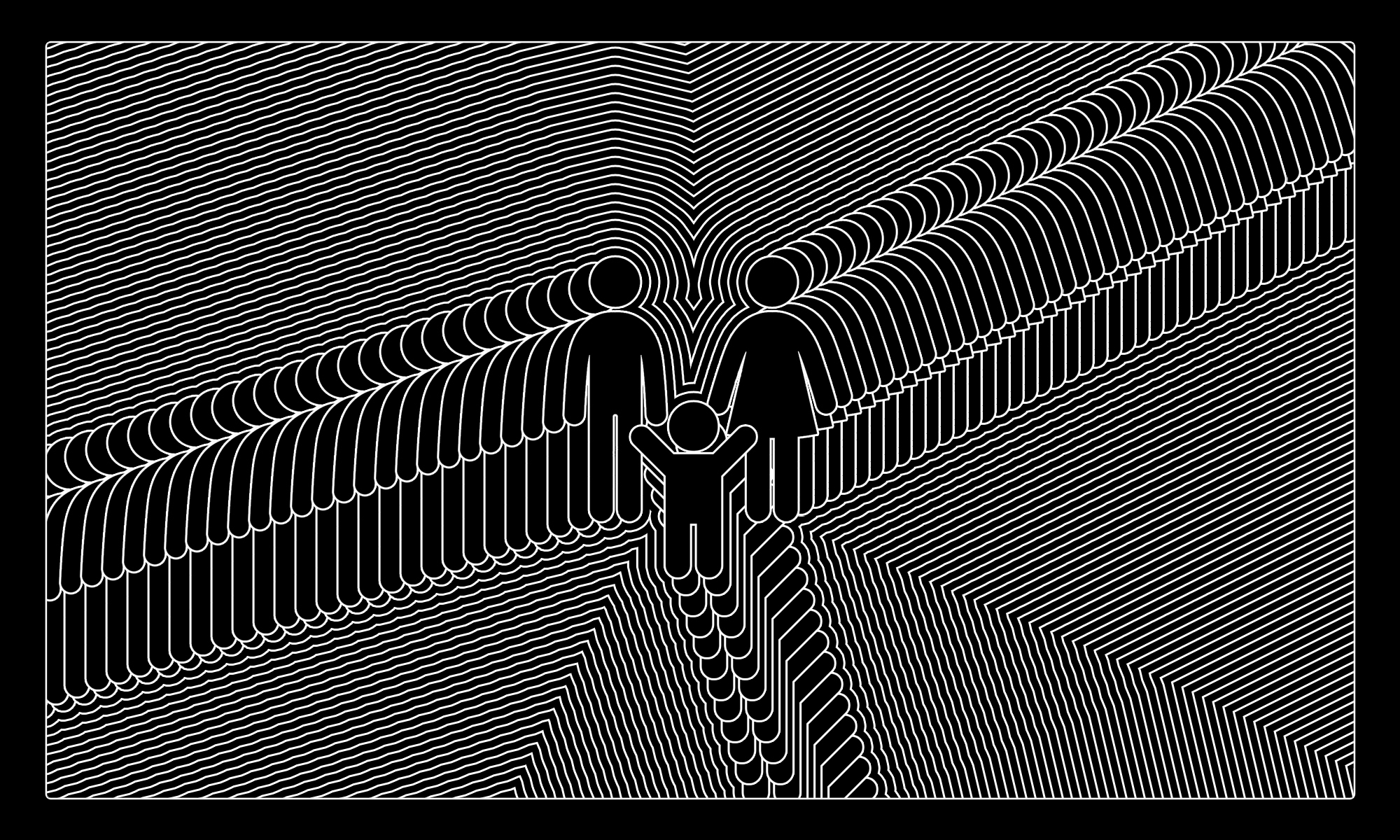

These two families, among the many I encountered while writing my recent book, Marriage and Family in Modern China, illustrate some of the extraordinarily widespread tensions in China. In the last 40 years, Chinese family structure has changed radically, from large families with deference to fathers and oldest sons to small families usually with a single son or daughter. This radical shift is the result of one of the largest social engineering experiments in history. Intended to stop uncontrolled population growth, and literally designed by a rocket scientist (probably because the Cultural Revolution had eliminated social science from academia), the unintended consequences of the One-Child Policy are now widely felt.

Clover’s family had not suffered the trauma of the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s or the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and ’70s. Nevertheless, as her parents’ only child, she was under the enormous pressure presented by the rapid development of China when parents only have one child, who often becomes their only hope for fulfilling their dreams, ambitions, and peace of mind that someone will look after them when they get old.

Dr. Hu and Mrs. Chen represent a very different picture. His story illustrates the plight of those families traumatized by the Cultural Revolution’s beatings and harassment of academics and wealthy landowners, the decimation of the educated middle class, and the large-scale family separations that left children without parents. Mrs. Chen’s history represents the effects of poverty, and the harsh, often abusive countryside family life. Both of them wanted to do better with their own child, but their expectations of each other that resulted from these traumatic childhood histories were so divergent that they had great difficulty constructing a satisfactory marriage.

Chinese families and China’s future

When the Communist Party took over China in 1949, it took control of marriages and families. Loyalty was no longer to the family and the emperor, but was now directed to the Party and the work unit. New marriage and divorce laws freed many women from punishing marriages, but marriage and divorce now required approval from the Party.

The traumas from the late 1950s until the 1970s — the Great Leap Forward, the Great Famine, the Cultural Revolution, and natural disasters — were assaults on both individuals and families. Then came the most serious blow to traditional families: the One-Child Policy under Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平, which restricted families to only one child. (There were exceptions for rural and minority families, but even those families were much smaller than before.) This grand social engineering experiment drastically altered China. Imposed birth control and abortions followed, leading to many girls being given up for adoption, abandoned, or even killed. Another unintended consequence was the disastrously small size of China’s labor force that persists to this day, and that will be responsible for supporting the large aging population.

The One-Child Policy also had positive unintended consequences. Because sex was no longer purely for procreation, women began to draw more pleasure from the act, as has always been the case for men. More importantly, the One-Child Policy empowered girls and women, because if a family had an only girl, she embodied the family’s future and was therefore as valuable as a son. The traditional Confucian ethic favoring sons was diluted, although not gone altogether. In many respects, women have achieved near parity with men, and have entered the ranks of the educated middle class in huge numbers (although women are notably absent from the most senior levels of government).

Furthermore, as families shrunk in size, kinship networks thinned, as people had fewer or no cousins, uncles, or aunts. In the past, family farms and family businesses had been conserved by passing them on to eldest sons, but that pattern was no longer sustainable.

There have been further revolutionary changes in families, as marital arrangements have evolved to become almost entirely “free choice marriages” rather than the “negotiated” or parent- and matchmaker-arranged marriages of prior eras. Older parents therefore experience diminished influence over their young adult children. In some families, aging parents, fearing for their future with their loss of influence, wreak havoc on their children’s young families. One couple told me how the husband’s mother, strongly against the marriage because of her loss of closeness to her son, had exerted her influence to force an abortion on the couple early in their marriage, only to try to take control of the child they eventually had. The emotional influence of his mother, an echo of the power parents traditionally had in their children’s marriages, once again put severe strain on this modern marriage.

The interior of China’s families is where national domestic policy lives

Because of the poverty of China’s social security system following the end of the “iron rice bowl” of guaranteed state employment, adult children are now required by law to support aging parents. Paradoxically, the fact that the government had to make such support legally mandatory shows that many young adults will not willingly shoulder this burden. Additionally, tragically, more than a million aging parents have lost their only child, and face a future without the financial or emotional support of their child.

Marriage and family patterns in China have evolved in ways that could not have been predicted 40 years ago. The new governmental campaign encouraging families to have more children comes when most couples refuse to return to a pattern of large families. In fact, many young people now say they want no children or no marriage at all.

Despite the factors I have enumerated so far, I continue to be impressed by the innate resilience in most families and couples I have encountered. For instance, another couple came to see us for a difficulty their obsessional 10-year-old son was exhibiting. He would spend hours deciding what to wear, washing his hands, or deciding if it was okay to eat candy. We soon discovered that his symptoms symbolized the difficulty he had pleasing both parents, who often disagreed and who had grown resentful of each other. But in our encounter, this couple quickly understood the unconscious constellation represented by their son’s symptomatic picture. They immediately took ownership of the situation, felt that we offered a clear path to improving their relationship, and showed ready determination to work on their marriage and on their son’s situation. Such resilience, too, will influence the future of Chinese families.

The future health of China’s families will determine the well-being of its people and of China as a country. This aspect of China’s makeup has been largely unexamined and unreported, but the interior of China’s families is where national domestic policy lives. The future of any country depends as much on the structure and well-being of its families as on its history, economy, politics, military, and environmental improvement. China watchers ignore the future of the Chinese family at the peril of missing the heart of the Chinese experience, and the implications of changing marital and family patterns for the future of China itself.

If you or anyone you know is having thoughts of suicide or self-harm, there are people who want to help: In the U.S., the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 800-273-8255. In China, the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center can be reached at 800-810-1117 or 010-8295-1332. Also, there is a list of suicide and emergency helplines around the world with links to more detailed hotlines.