Radical radicals

Huang Jenwei on the emotions of written Chinese

This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. In the work of Taiwanese designer Huang Jenwei, this adage becomes quite literal.

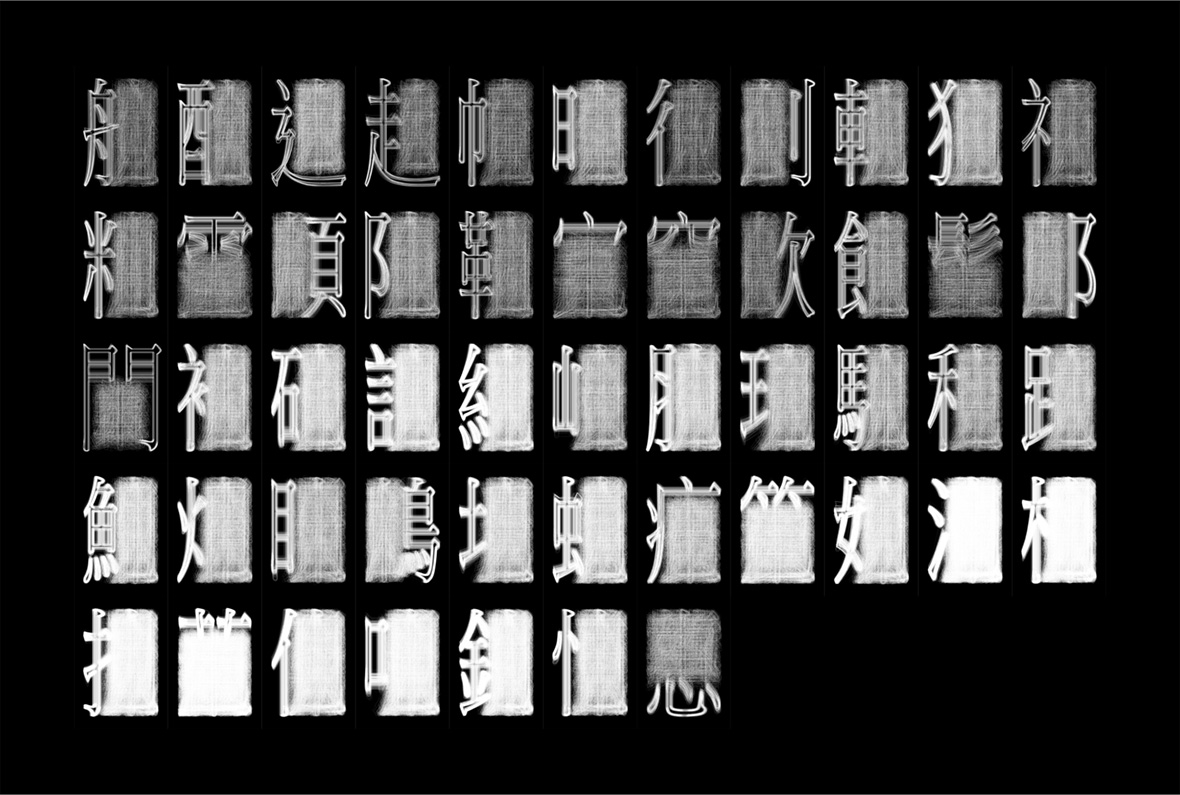

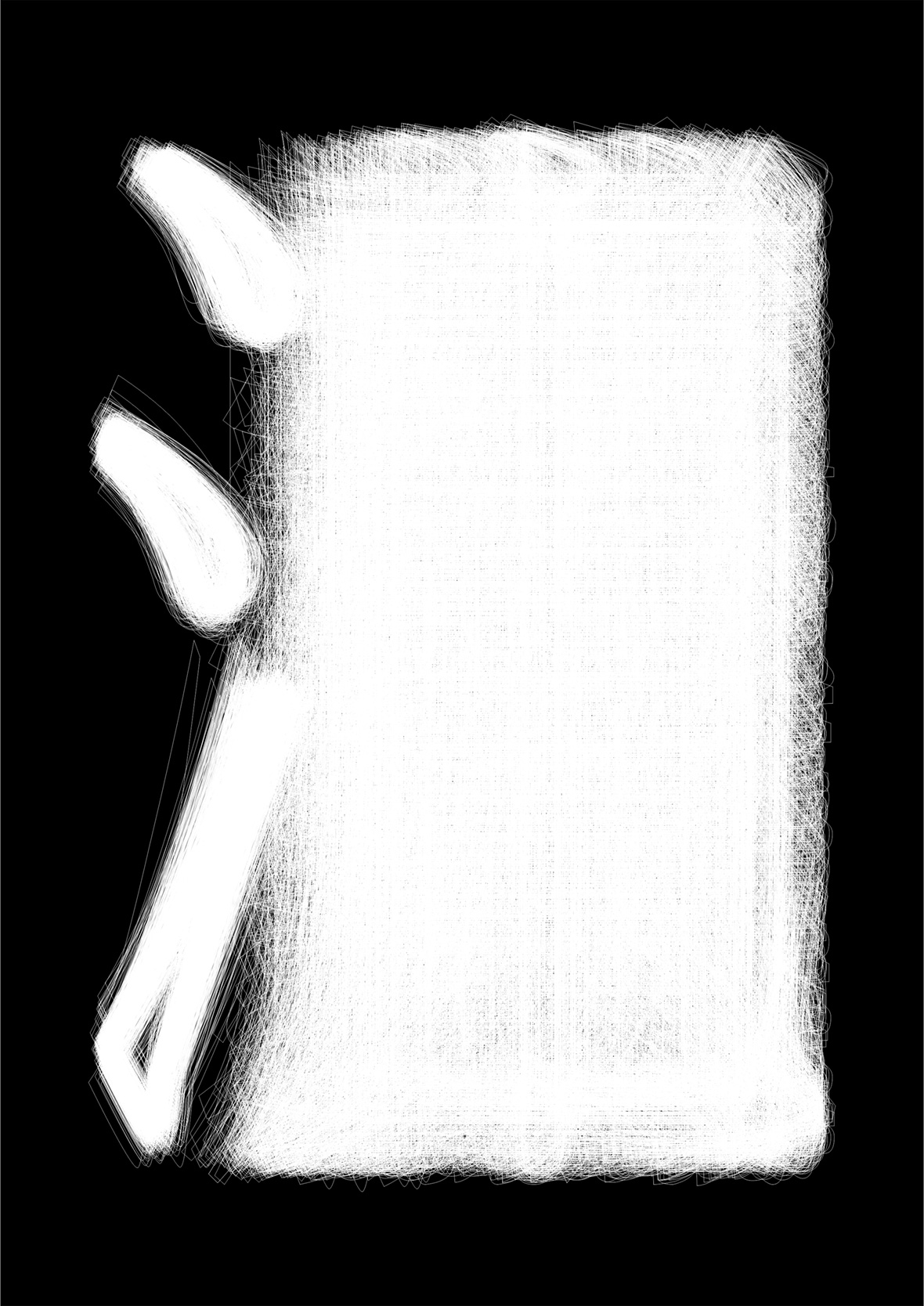

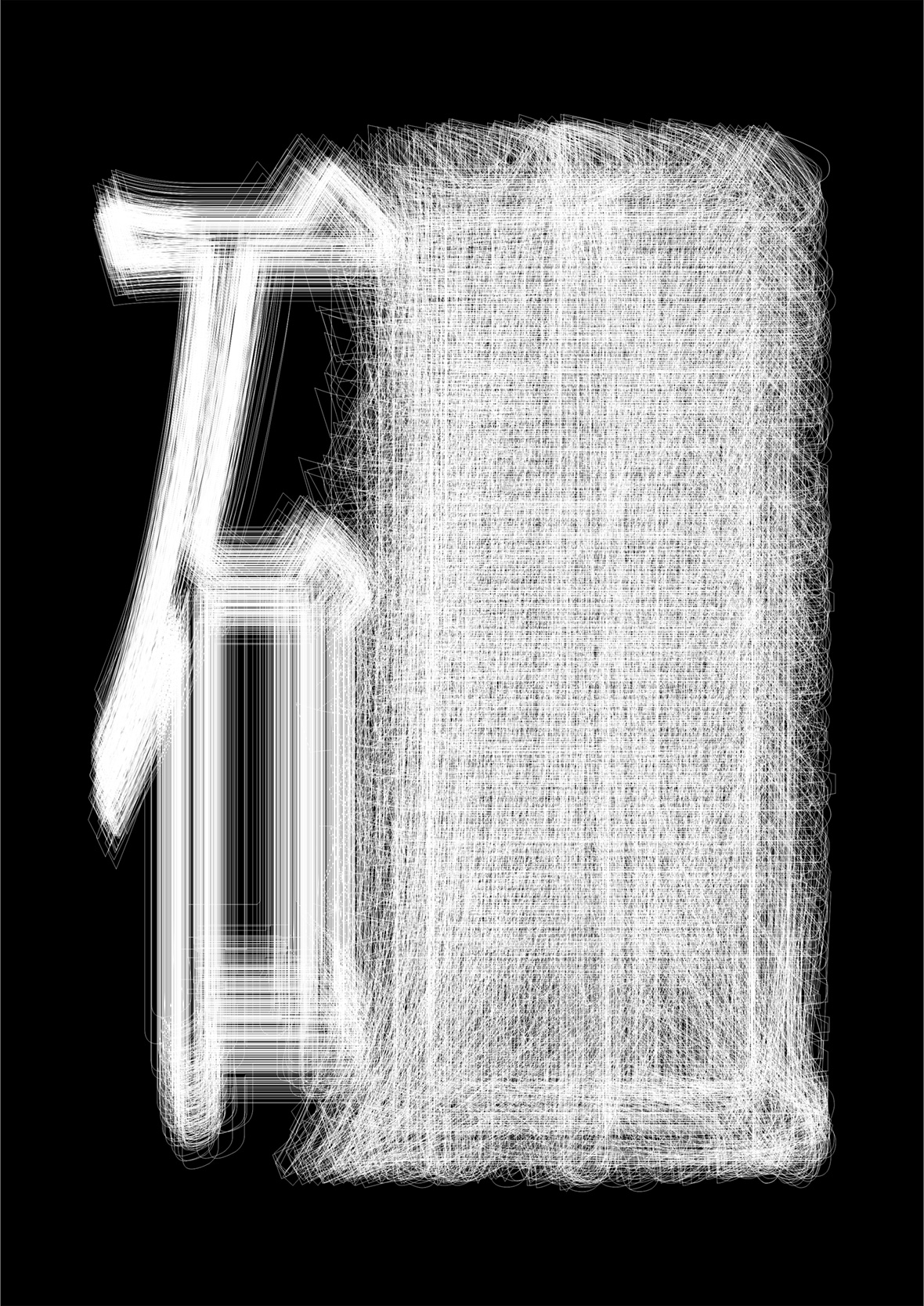

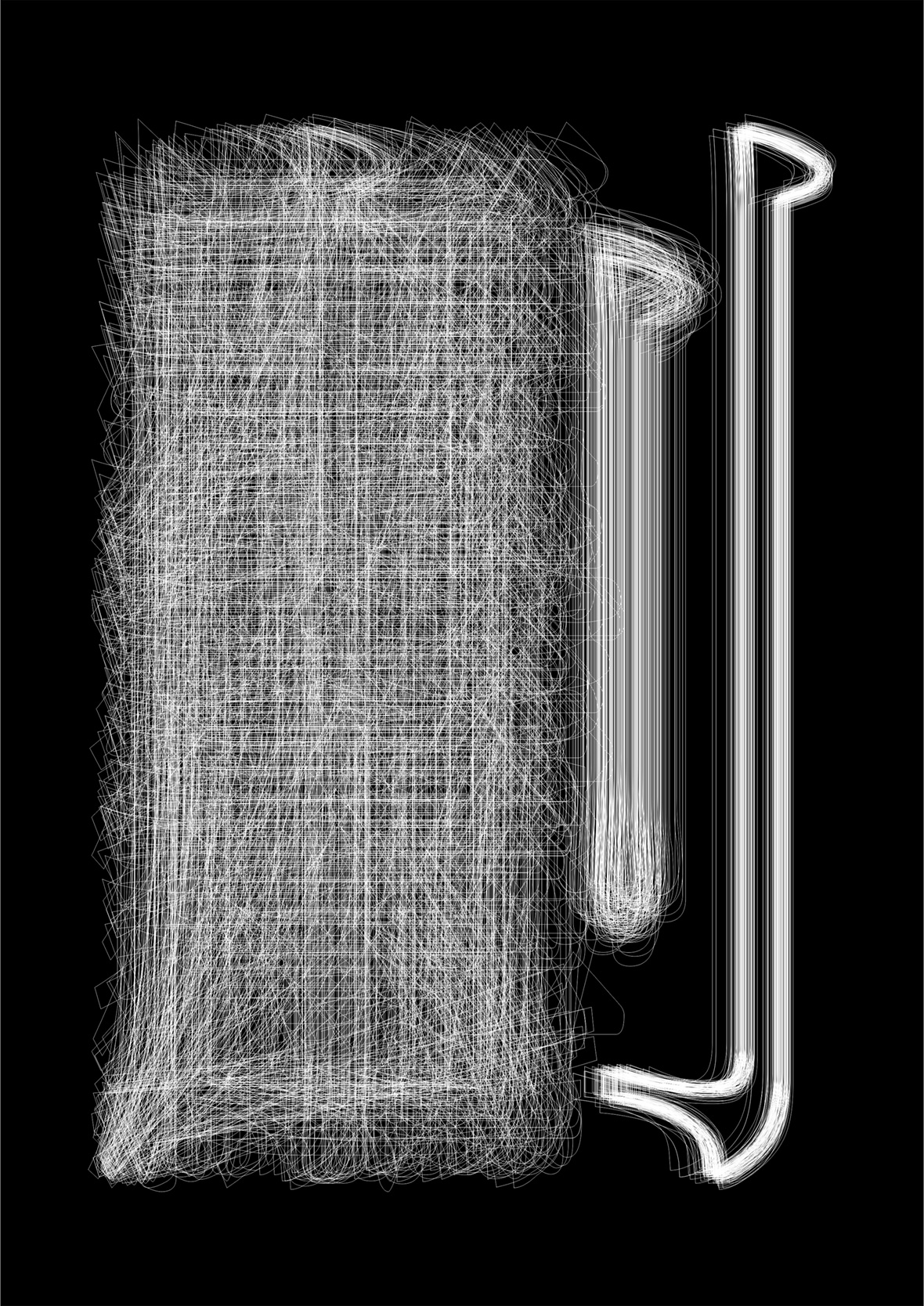

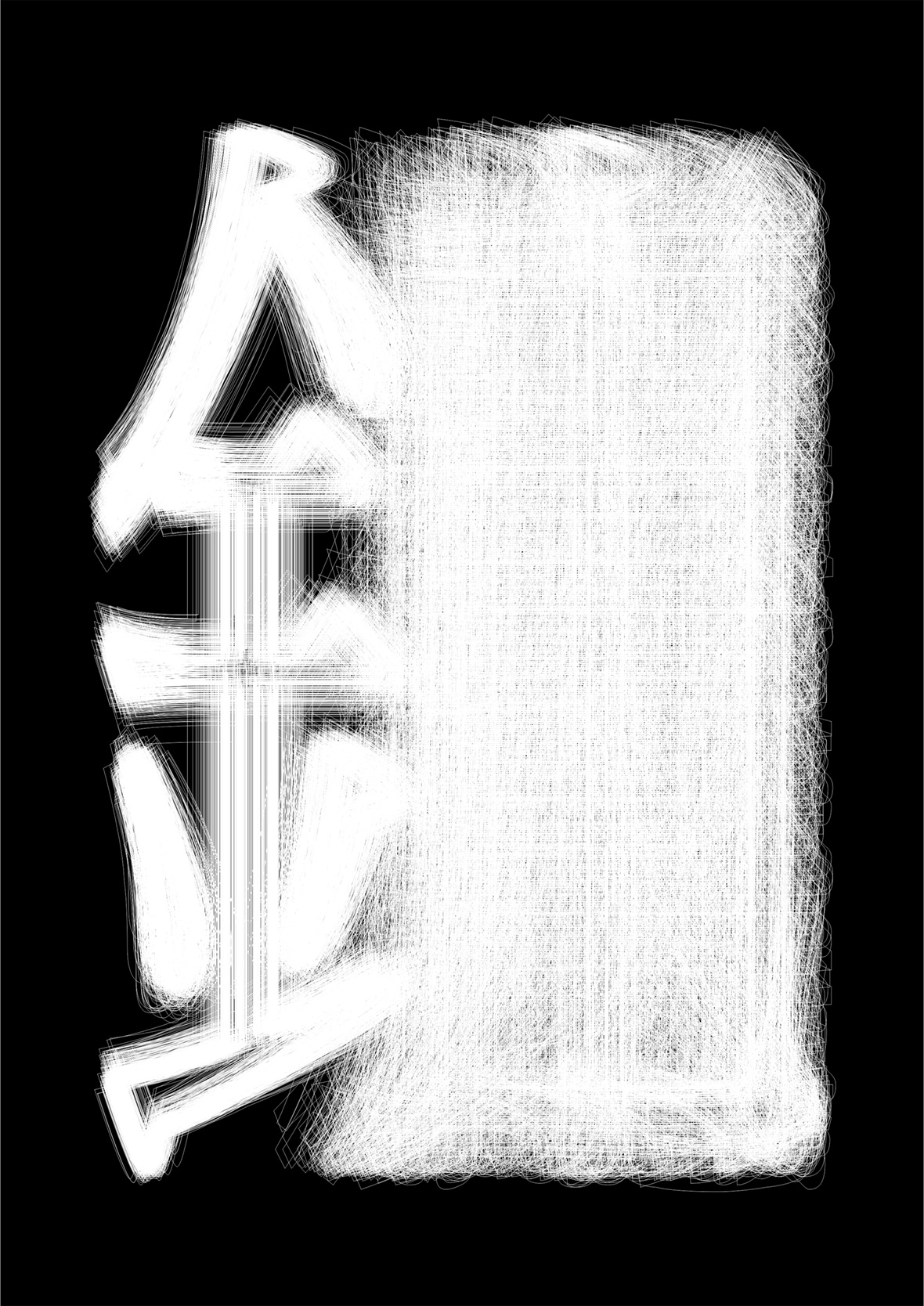

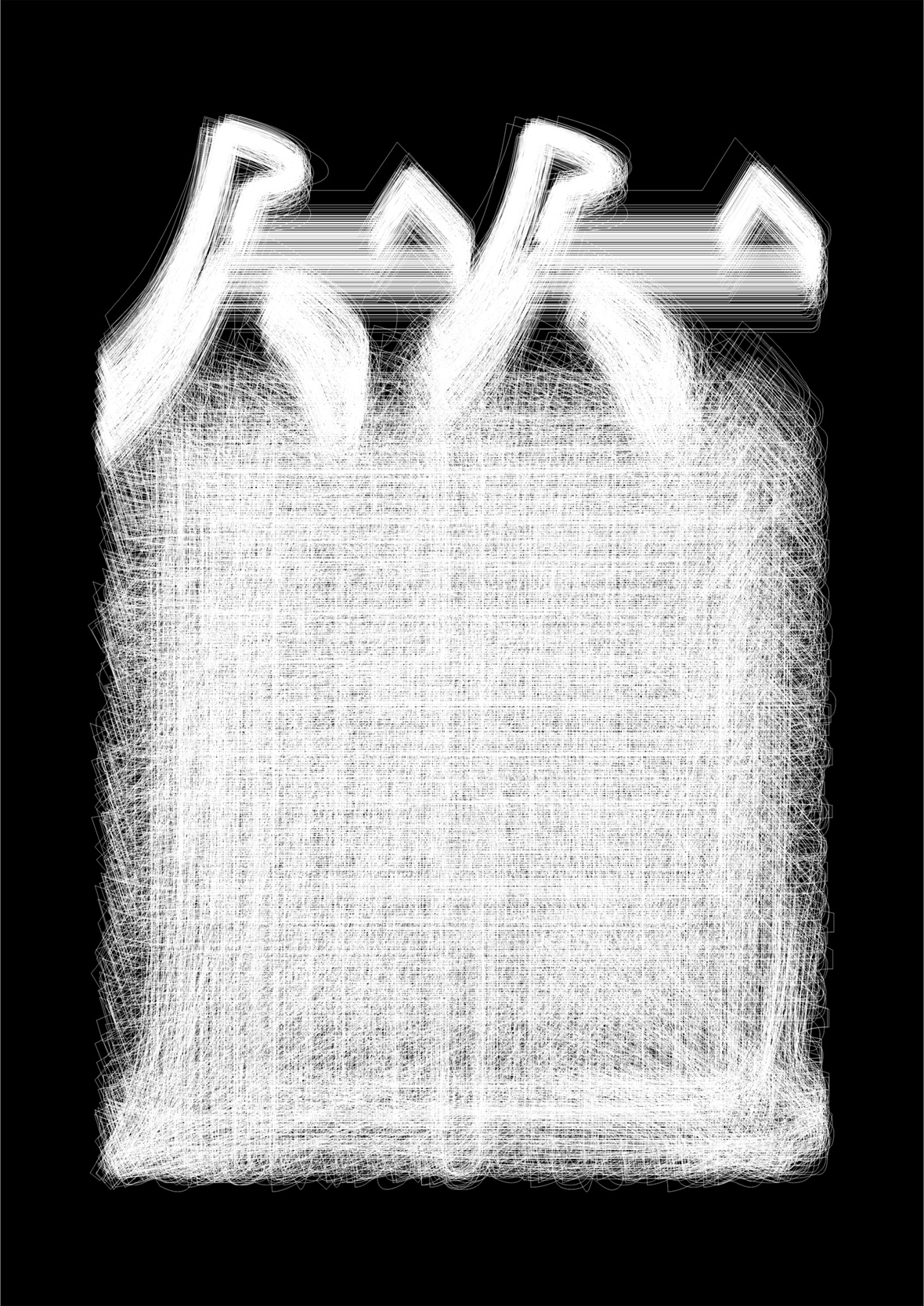

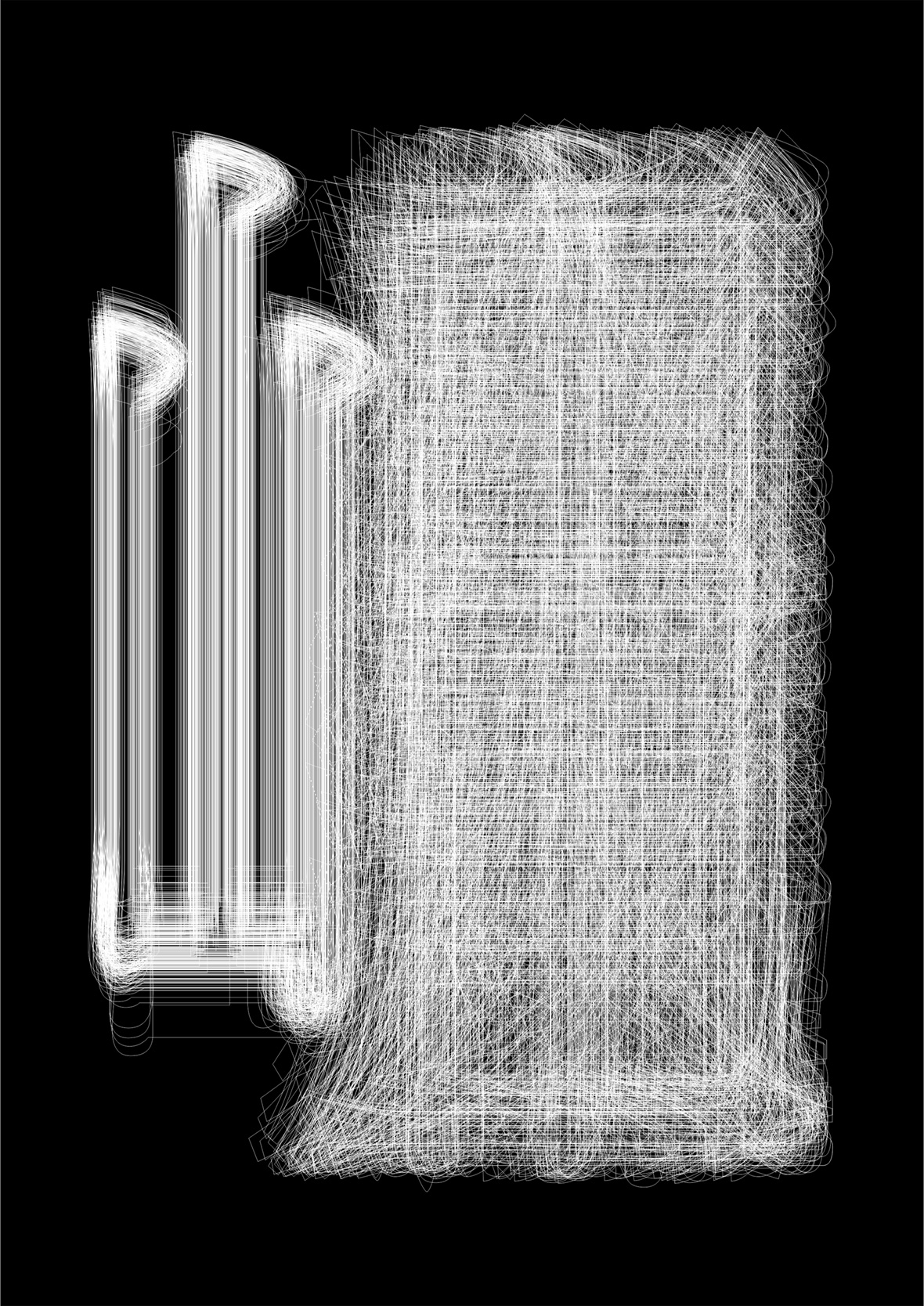

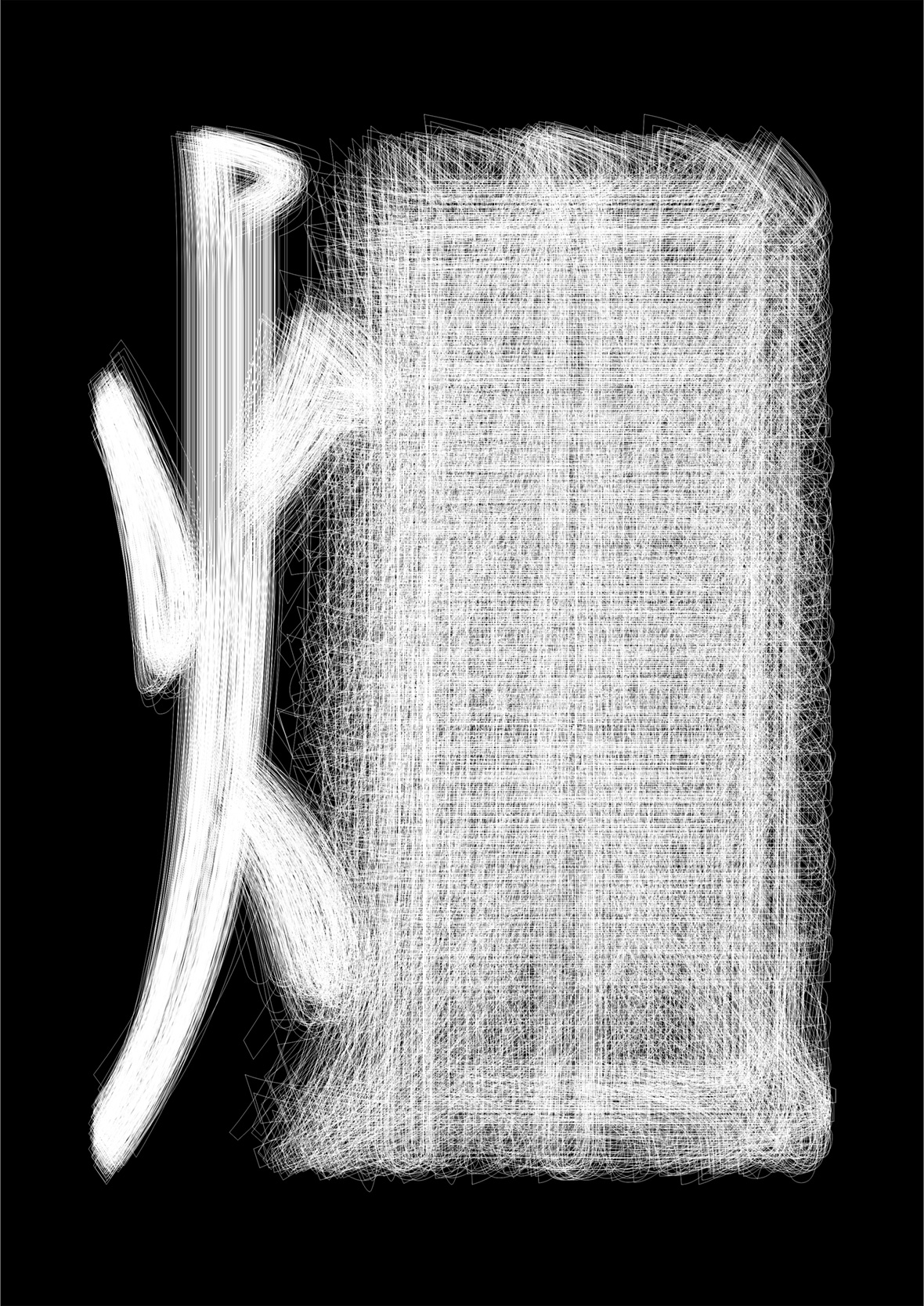

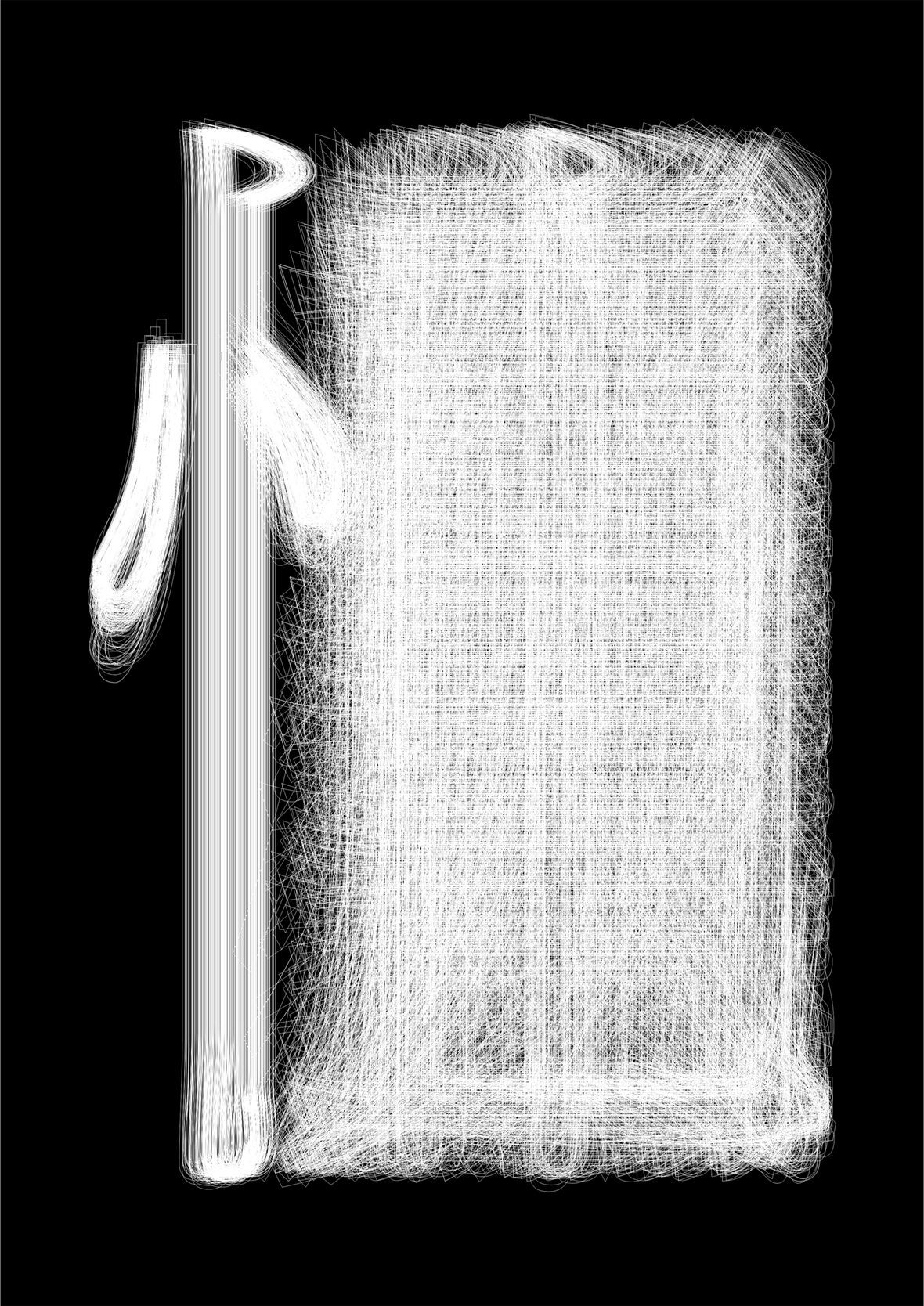

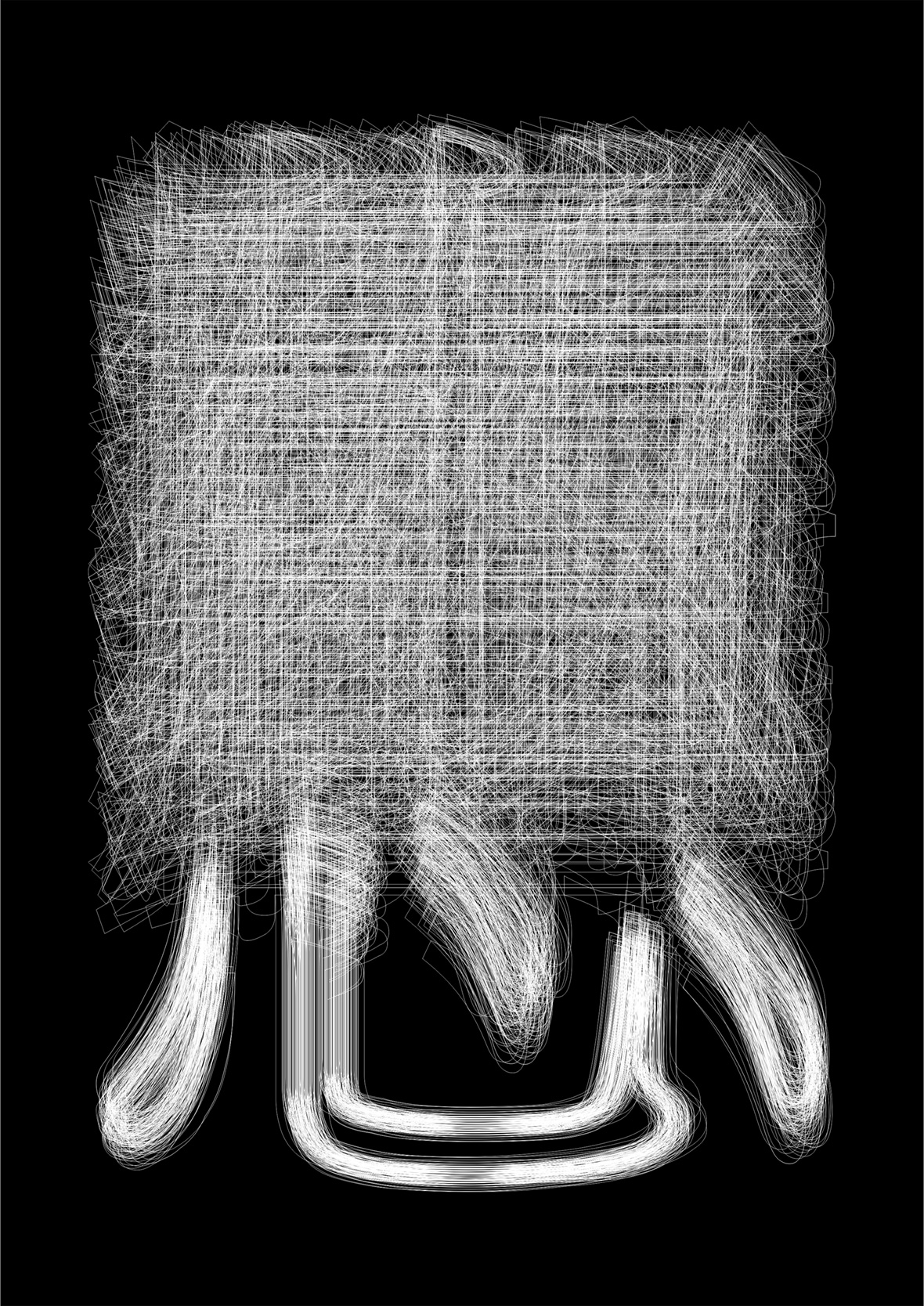

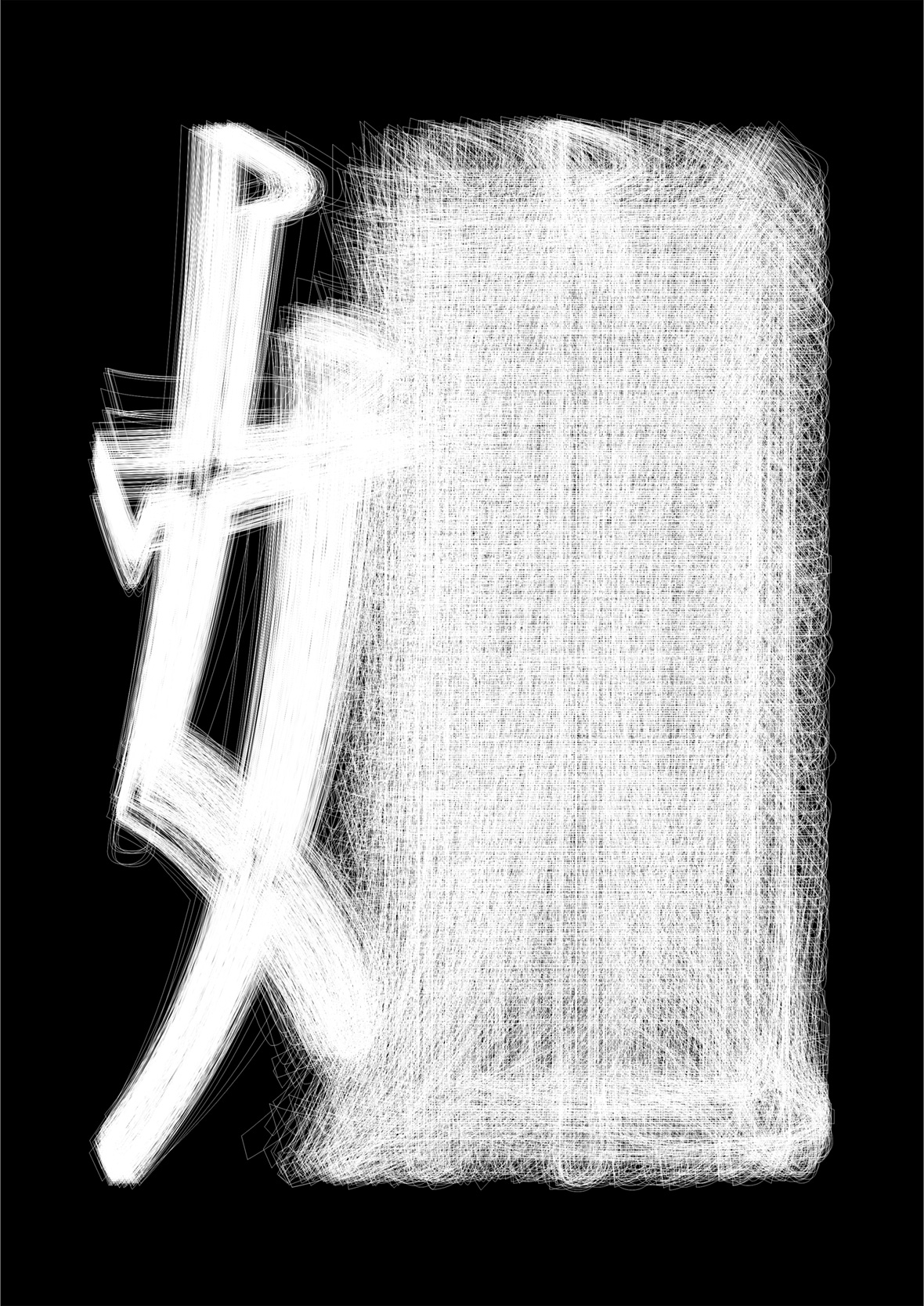

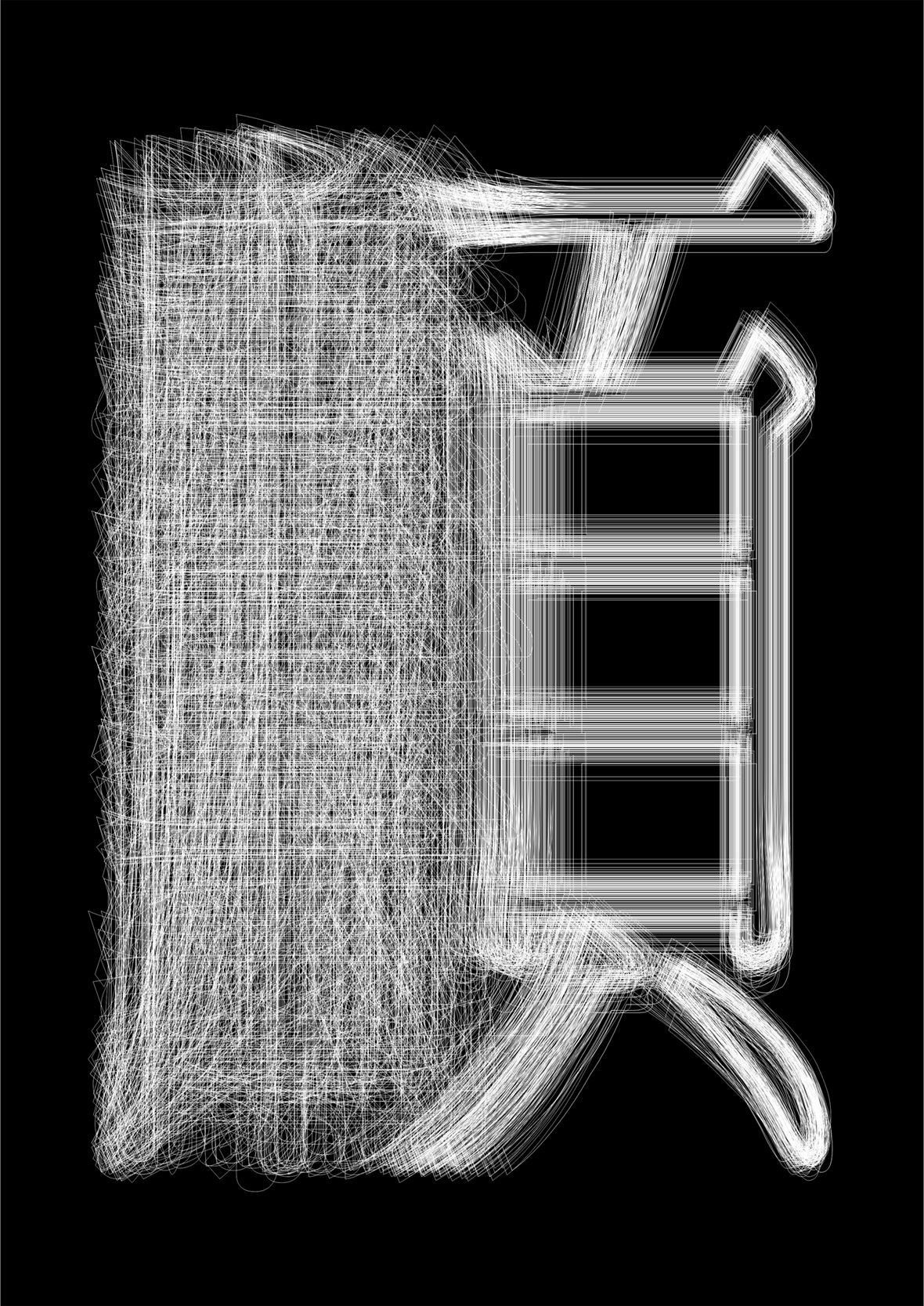

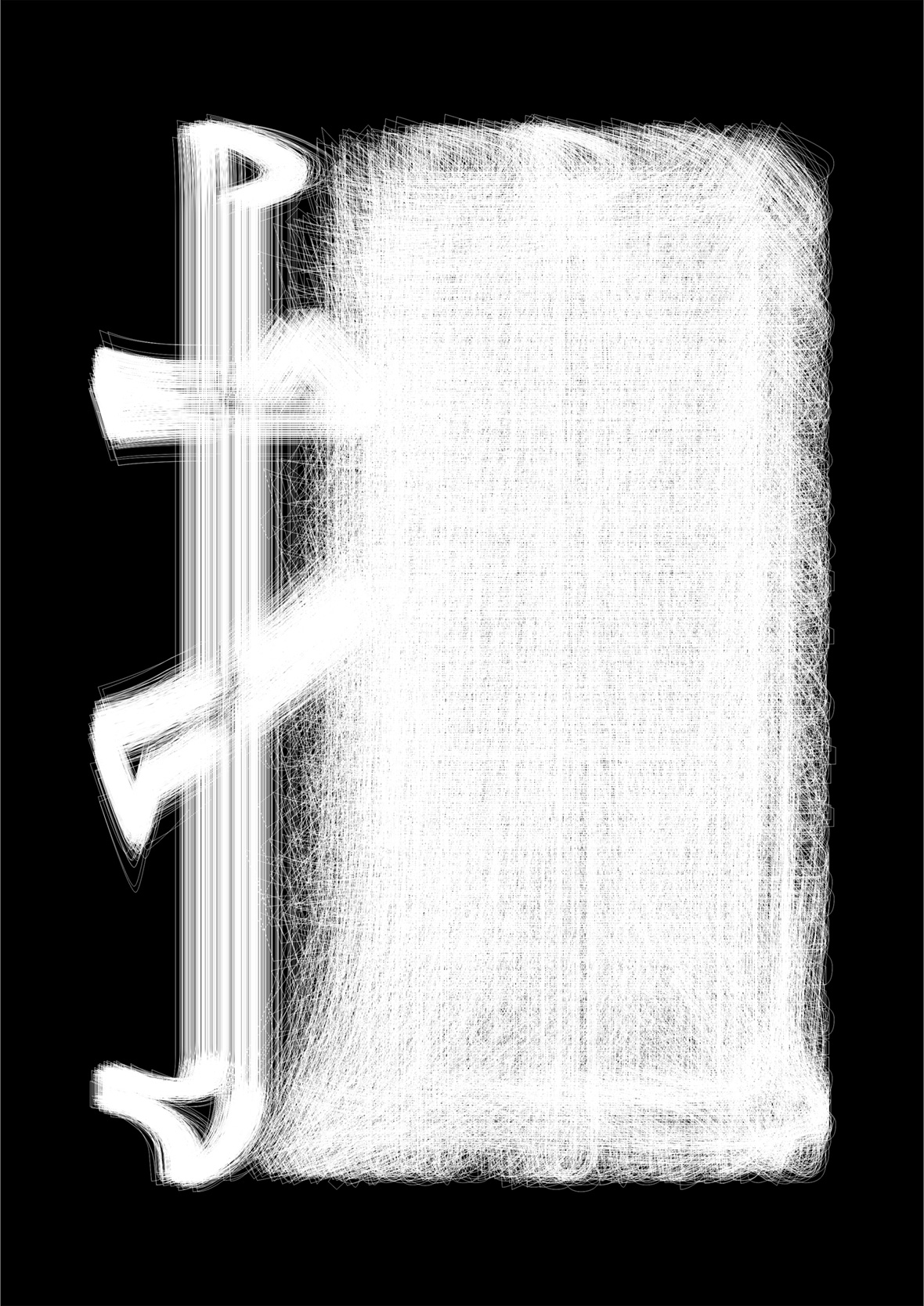

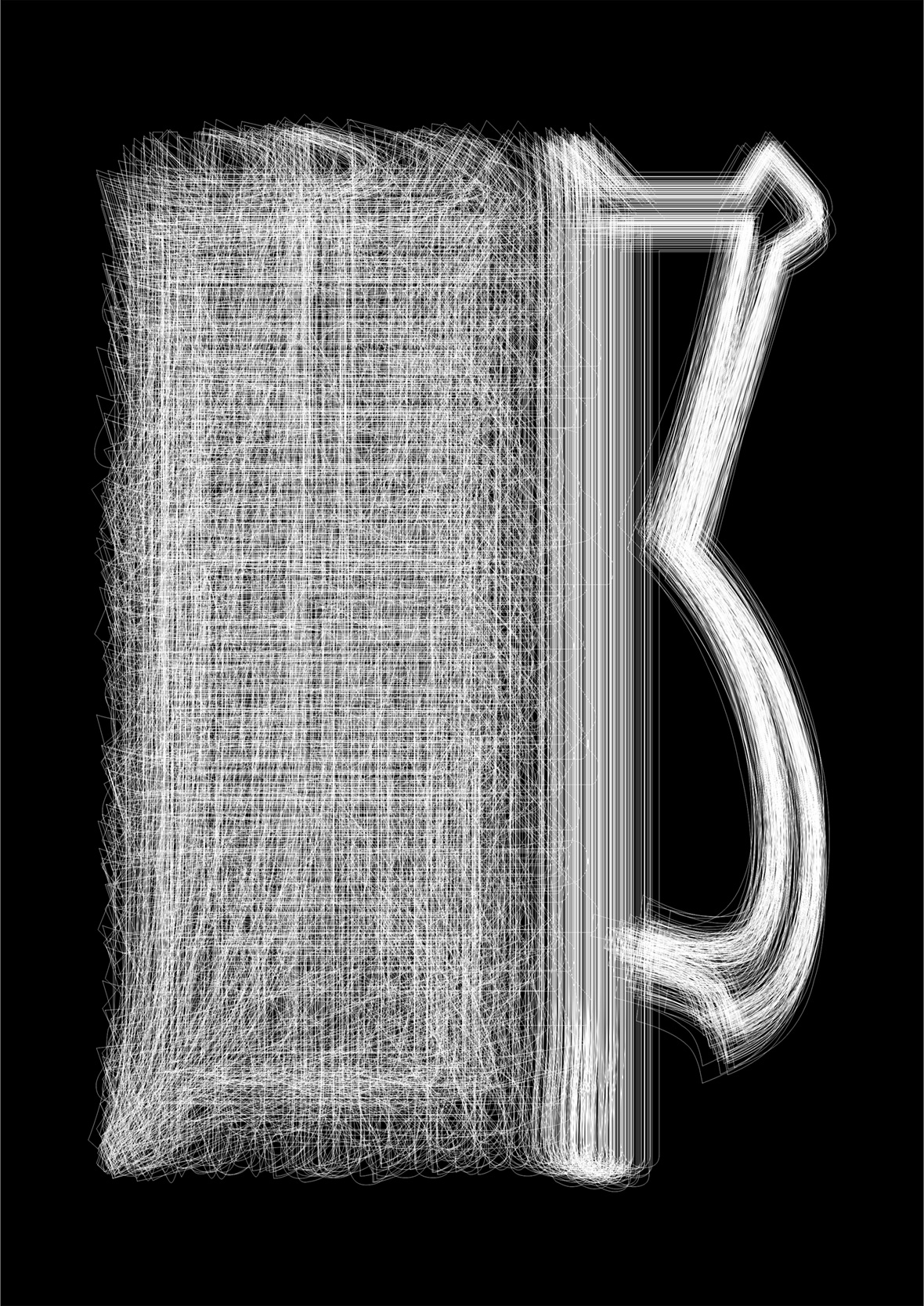

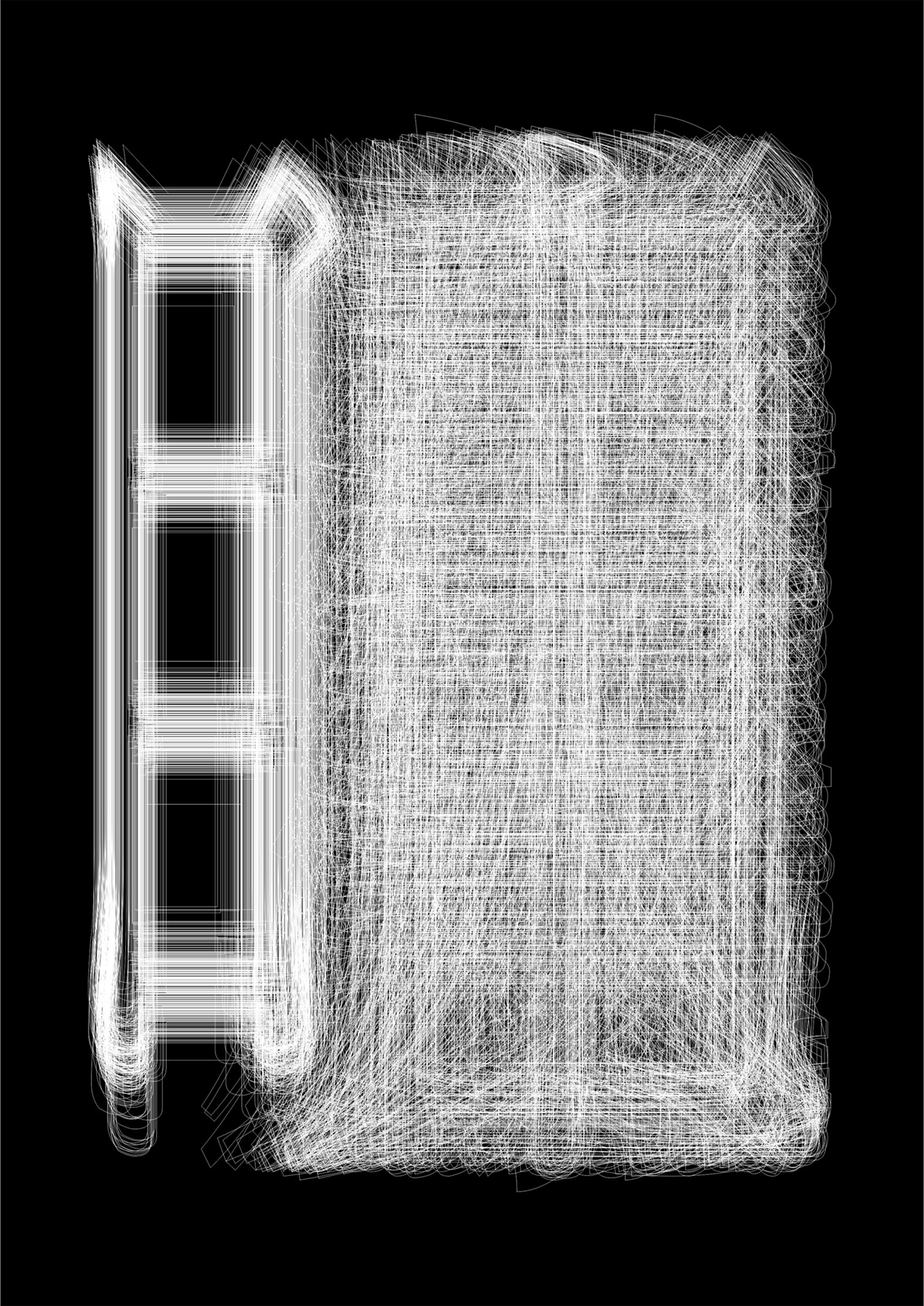

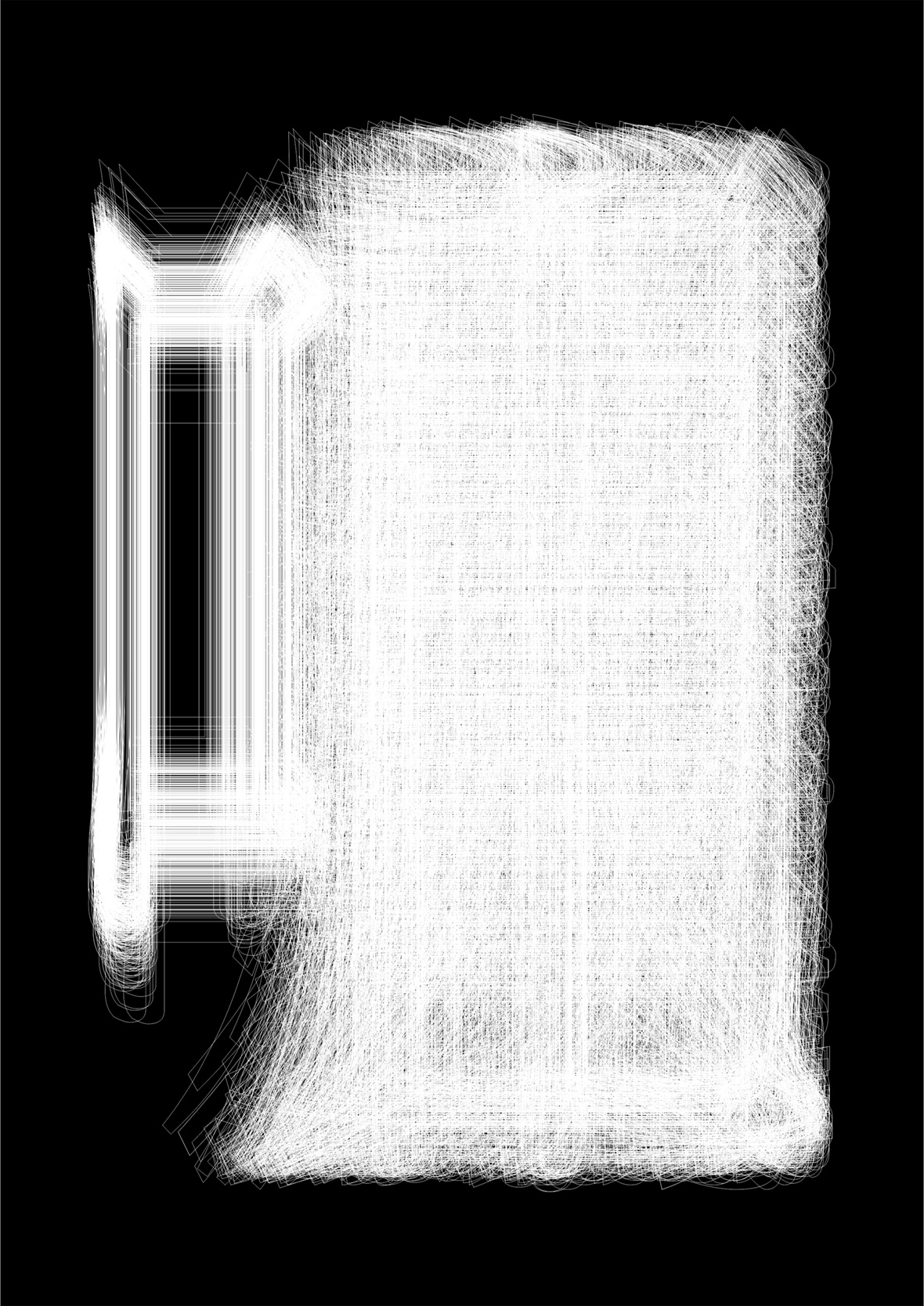

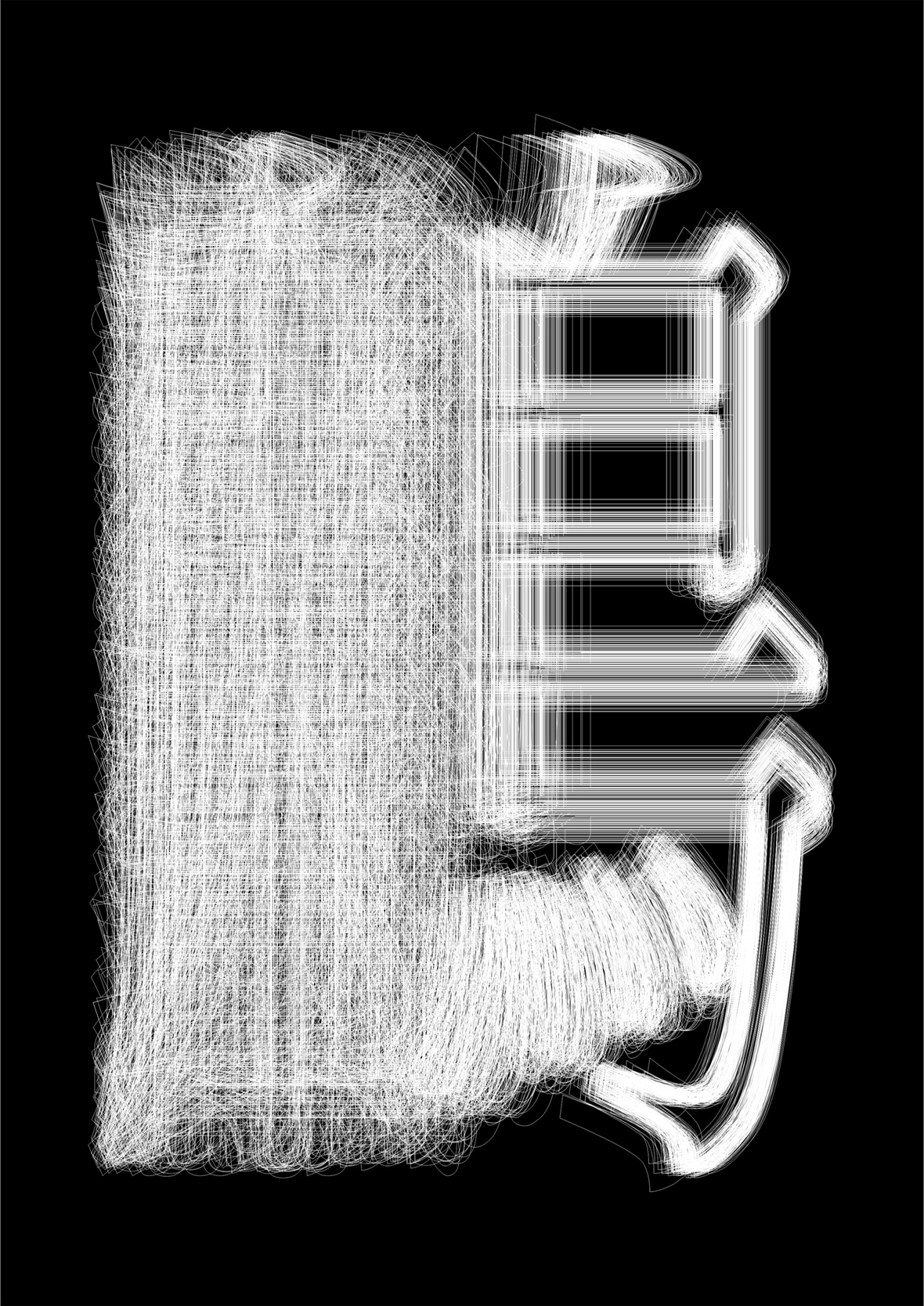

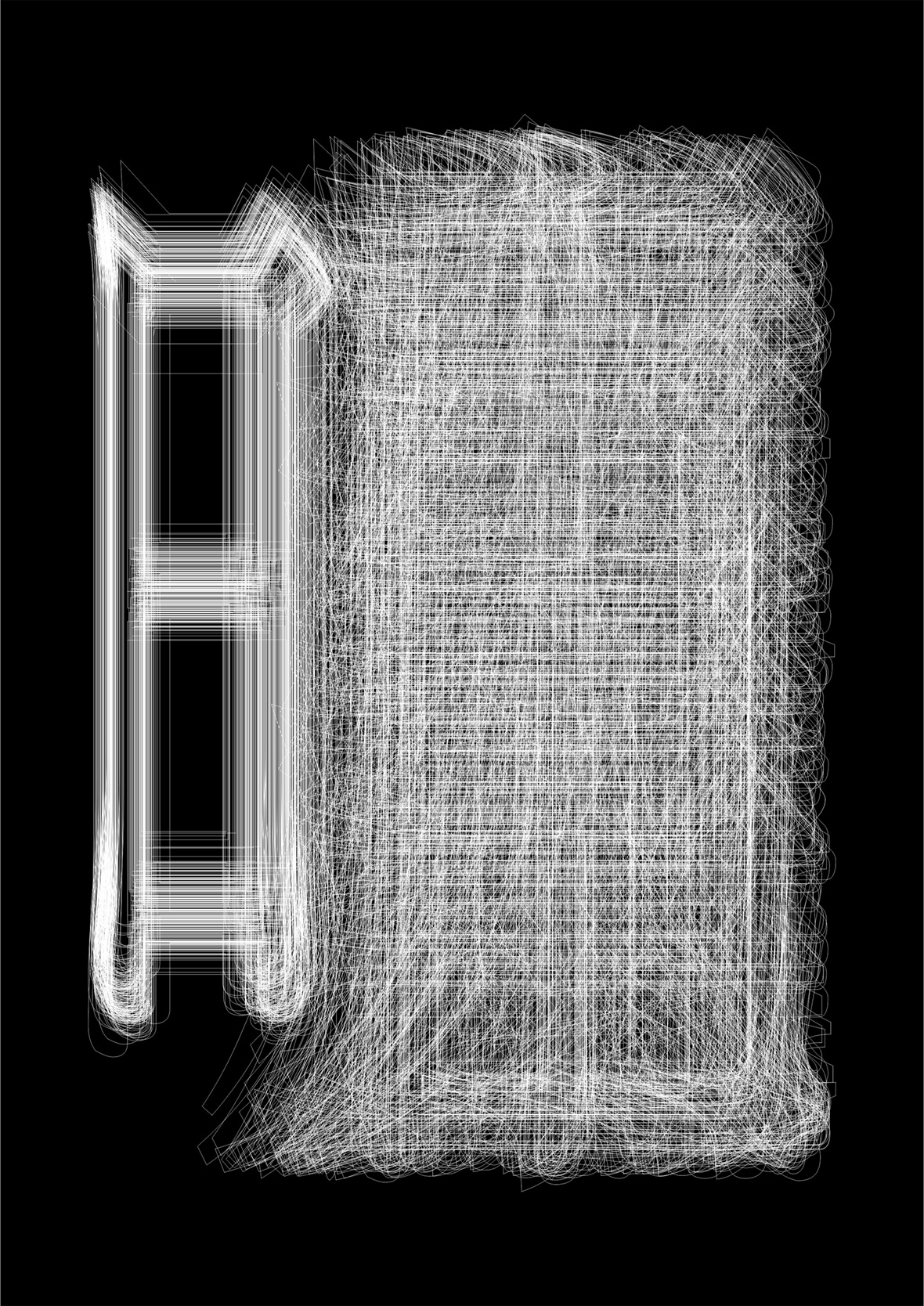

In a project titled Hanzi Gong, he’s created black-and-white posters assembled from 18,046 Chinese characters out of the Kangxi Dictionary—the definitive dictionary of imperial China between the 18th and early 19th century. Each artwork revolves around a radical, the foundational component of written Chinese. Certain radicals are more widely used in the language, and in Huang’s series, the number of words that incorporate each radical can be delineated with how opaque each letter is. The more characters that are layered on, the denser the frame—some are almost a solid white, while others are translucent grays.

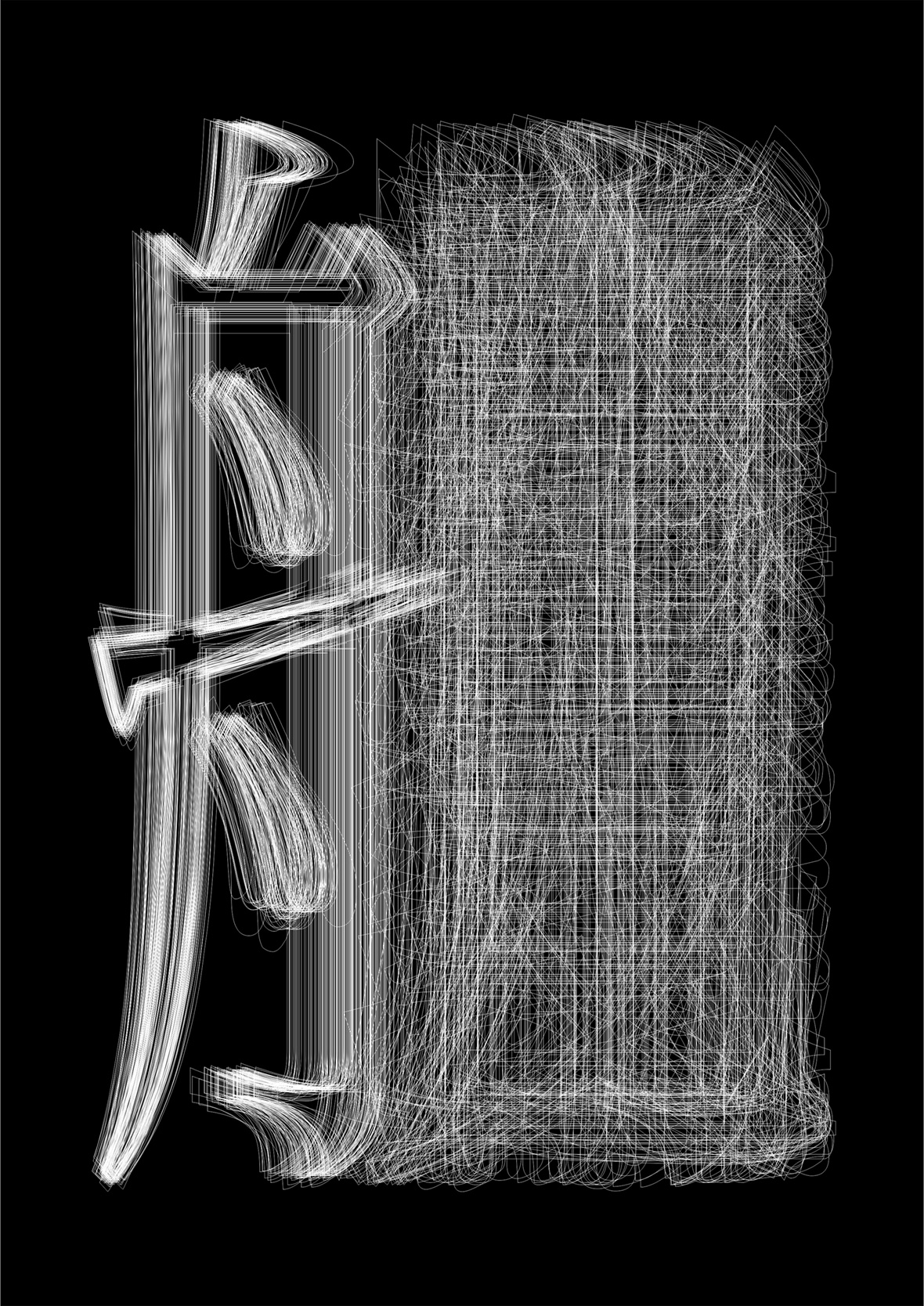

Take, for example, the radical “wood” (mù 木), which is used in 1043 characters in the Kangxi Dictionary. Stacking them all together, Huang forms a near-impenetrable, cocoon-like entanglement of white lines. As the radical sits in the same place in every character, it’s the only part that’s easily legible. The rest of the character is familiar yet foreign.

Hanzi Gong was inspired by a simple idea: throughout our lives, we experience countless emotional ups and downs, and language is one of the most frequently used mediums in expressing these experiences—but what if language itself could experience and express emotions of its own? What might that look like?

For the project, a total of 51 radicals were given a similar treatment. Through these typographic abstractions, Huang explores the emotionality of the Chinese written language, and how its expressive qualities still very much persist in a digital format.

In Chinese calligraphy, the weight, length, and angle of different brushstrokes can convey mood and emotion. However, it’s typically thought that these expressive qualities are missing when they appear as computer fonts. Huang doesn’t believe this is necessarily the case—though they may not convey the full range of personality of handwritten formats, there’s still a level of emotionality to be found. “Every individual ideographic Chinese character can express moods, traits, and aspirations,” he explains. “It’s a form of expression that’s uniquely Chinese.”

For the project, Huang settled on a Songti typeface, which can be considered the Chinese equivalent of sans-serif. Compared to Kaiti or Heiti fonts, he believes Songti is a font more grounded in everyday life, offering a certain level of relatability for readers. He also sees it as most closely resembling the typeface found in earlier versions of the Kangxi dictionary. “It’s a common font, often used in commercial prints,” he notes. “Heiti, due to its thick strokes, is more solemn; Kaiti is sensual and emotive; and Songti strikes a balance—it’s a font that’s structured, legible, and expressive.”

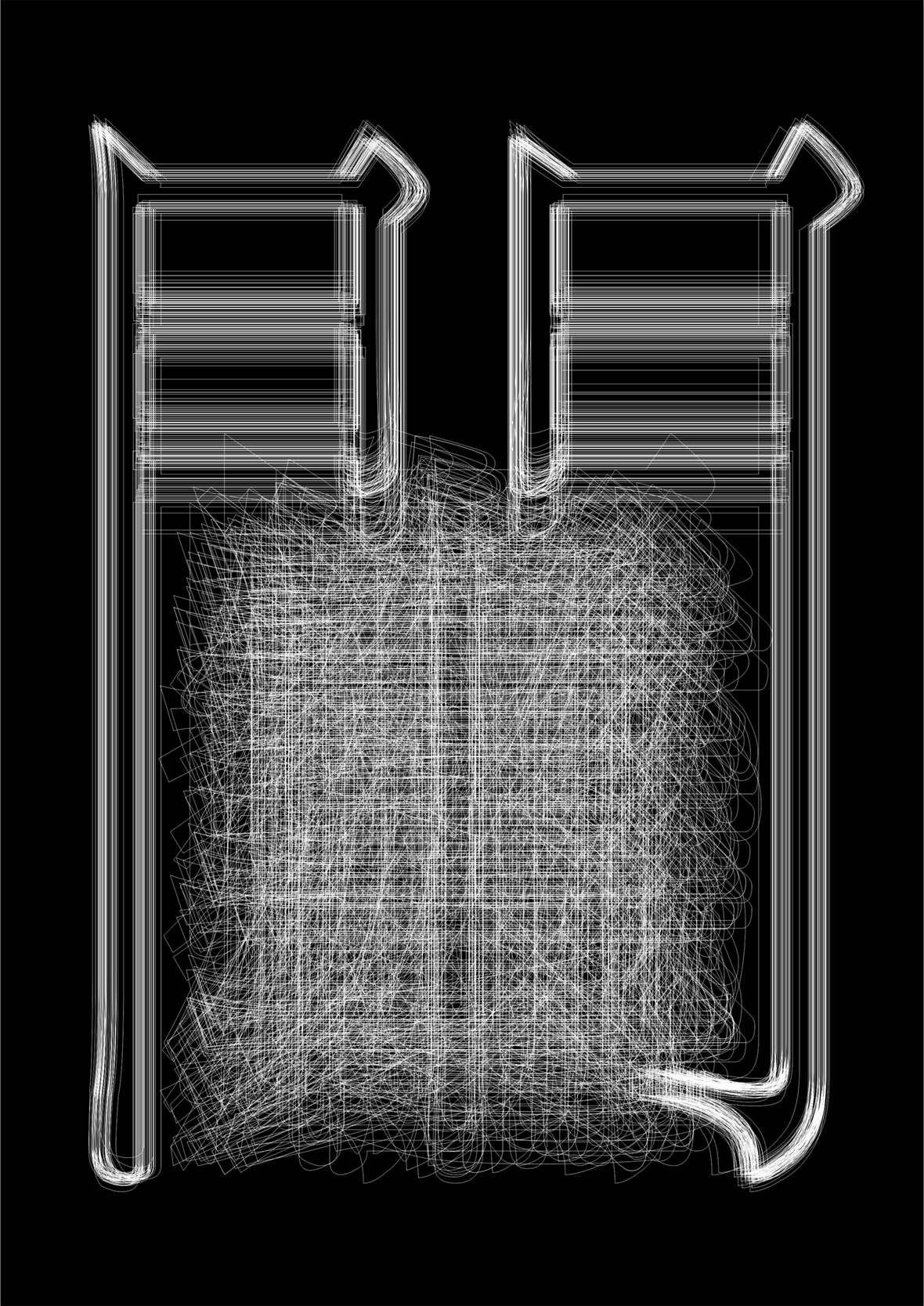

Of the entire project, Huang’s favorite posters are the two revolving around the radical xīn (心), meaning “heart.” Unlike most other radicals, xīn (心) comes in varying forms and positions. At times, it appears as a bottom radical, while other times, it appears on the left. One particular character of interest made with the radical xīn (心) is xìng (性)—a common Chinese suffix that turns verbs and nouns into adjectives. It’s used to describe a certain essence or quality, such as emotionality (gǎn xìng 感性), rationality (lǐ xìng 理性), and variability (biàn huà xìng 變化性). Other characters that incorporate the xīn (心) radical are similarly meaningful to Huang, especially those used to speak to different states of the human condition. “It’s a radical used in characters that help express our inner selves—whether it be our mood xīn qíng (心情) or our thoughts sī niàn (思念),” he says. “It’s an essential part of expressing what it means to be human.”

Huang cites Russian abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky as a source of influence, pointing to philosophies outlined in his 1926 book Point and Line to Plane. In it, Kandinsky meditates on the emotionality of painting and how simple lines can infuse an artwork with drama and force. Huang believes these concepts apply to Chinese writing as well. The lineage of the language means each character comes with meaning that has persisted and evolved with time, though these subtleties are often only intelligible with a thorough understanding of Chinese history and etymology. “Chinese is one of the four oldest scripts in the world, and the only one that’s still in use today,” he says, “The cultural history of the Chinese written language gives each character a lot of depth and meaning.”

But even without an exhaustive grasp of Chinese etymology, people who can read the language are still able to find personal meaning in each character. Depending on the individual viewing the artwork, they may spot different components emerging from its complex layers, and thus, identify specific words. This is entirely by design. “The Chinese written language has human qualities, in that they’re both everchanging and unchanging at the same time,” Huang says, noting that it’s all a matter of perspective. “Ultimately, the abstraction of these characters is an expression of the fluctuation of life and emotions.”

Behance: ~/jenweihuang

Contributor: David Yen

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li