Below is a complete transcript of the Sinica Podcast with Megan Walsh.

Kaiser Kuo: Welcome to the Sinica Podcast, a weekly discussion of current affairs in China, produced in partnership with The China Project. Subscribe to The China Project’s daily Access newsletter to keep on top of all the latest news from China from hundreds of different news sources. Or check out all the original writing on our site at supchina.com. We’ve got reported stories, essays and editorials, great explainers and trackers, regular columns, and, of course, a growing library of podcasts. We cover everything from China’s fraught foreign relations to its ingenious entrepreneurs, from the ongoing repression of Uyghurs and other Muslim people in China’s Xinjiang region to the tectonic shifts underway as China rolls out what we call the Red New Deal. It’s a feast of business, political, and cultural news about a nation that is reshaping the world. We cover China with neither fear nor favor.

I’m Kaiser Kuo, coming to you from Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

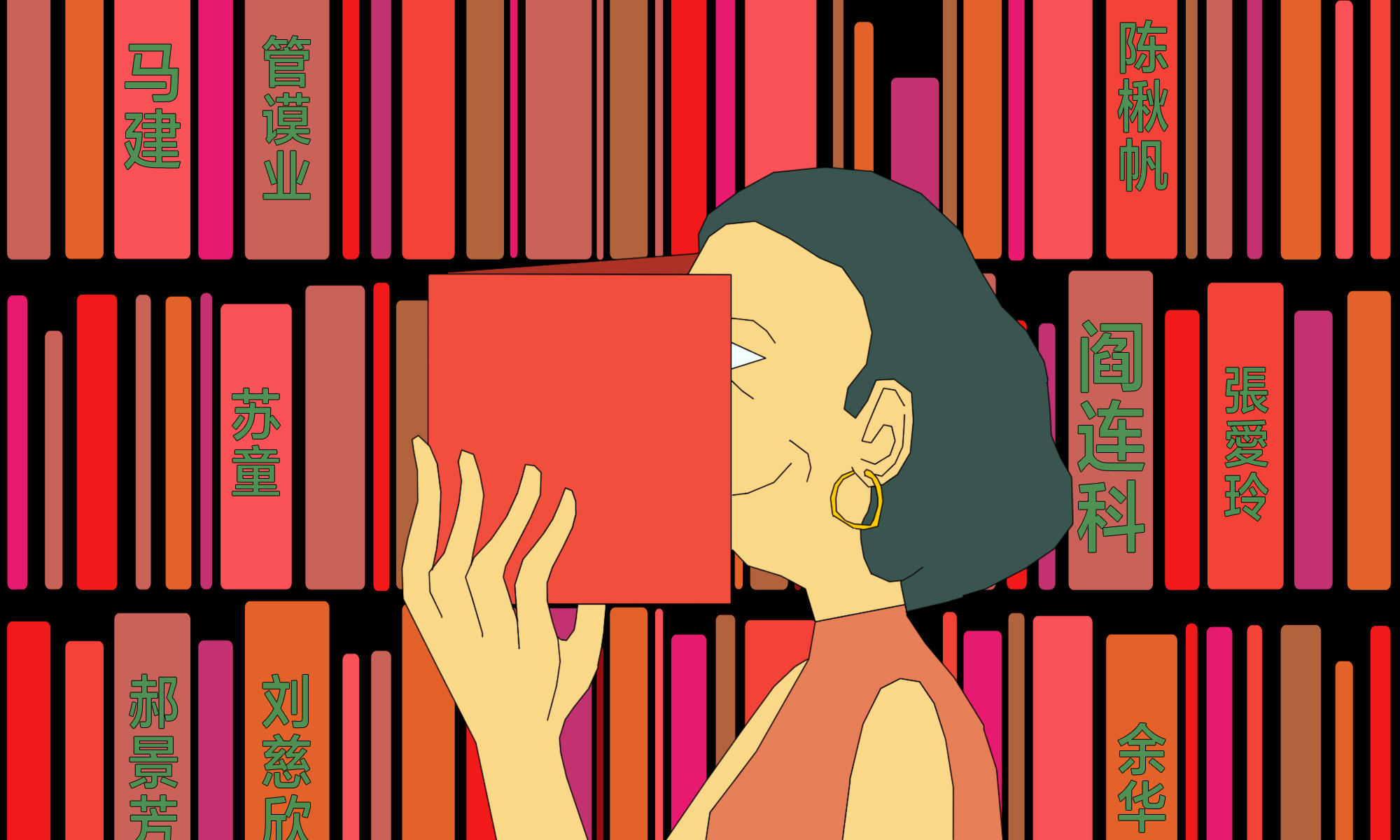

If you’ve been listening to this podcast in the last several weeks, you’ll know that I’ve got something of a theme going, looking at the different ways we approach understanding China. As with any society, I hope it should go without saying that one vital perspective on it should be its humanities. Without a sense of the role played by the arts and letters — by culture of all “brows,” as it were — can we really say that we know anything about a society? That’s why I was really excited to see a new book by Megan Walsh called The Subplot: What China Is Reading and Why It Matters.

Immediately, I thought that a conversation with the author would slot right into this series, and on reading the book, I was not at all disappointed. Megan Walsh is a journalist who lived and worked in Beijing for a number of years in the 2000s and early 2010s. She studied Chinese literature extensively at SOAS and has done the English-reading world a great service by producing a remarkably slim little volume that nonetheless covers a huge range of Chinese writers from the country’s better-known, well-established authors like Mo Yan and Yan Lianke to migrant workers, from genre fiction writers working in pulpier categories like detective or crime fiction and romance to the science fiction writers like Liu Cixin, Hao Jingfang, and Chen Qiufan, who’ve drawn quite a bit of attention lately — and also (and this is the really crazy part) to the legions of mostly anonymous writers who churn out just tens of thousands of characters literally a day to feed the insatiable appetite of fans, who are mostly commuters, I guess, reading serial stories on their smartphones. And while these are mostly lacking in what one might think of as conventional literary merit, they are certainly popular and they’ve been the basis for just about every TV show produced in China and popularized on China’s many streaming services in recent years.

So just like you need to view China through a bunch of different lenses, you need to view China’s literary scene through a full array of genre lenses as well to get a clearer picture and that’s what Megan’s book, The Subplot, delivers. Megan Walsh, welcome to Sinica.

Megan: Thanks so much for having me, Kaiser.

Kaiser: So delighted that you could join. So, Megan, like many people who are first exposed to modern Chinese literature, your first love was Eileen Chang, if I’m not mistaken, Chang Ai-ling. You wrote extensively while at SOAS, about another woman writer, Ding Ling, who was just a hugely, hugely influential author in the mid-1920s and 1930s. But talk about your early exposure to what we would call contemporary Chinese fiction. Who were some of the authors writing, say, from the ’80s onward who really first grabbed you?

Megan: The first writer that I really actually properly engaged with was Ma Jian. It was around the time of Beijing Coma. I reviewed it while I was working at the Times of London book section. And I also got the opportunity to interview him, and –

Kaiser: Oh, wow.

Megan: … he was just such a firecracker. He really didn’t pull any punches. And I found his anger and clarity of expression and ideas, incredibly energizing when I spoke to him. And I guess, even though I’d lived in China before that, he was the first author that I properly engaged with, in a meaningful sense, once I got back. And that’s then what knocked me into people like Yan Lianke who I still would probably say is my favorite from that era. And then obviously, Yu Hua and Mo Yan and Su Tong.

Kaiser: Yeah, so those are five of the biggest writers of that age. But they just represent one corner of the spread of genres that you cover. The sheer number though, I mean, I feel really… I was blown away by all that you seem to have read. The number of just novels and short stories that you reference in this book of yours is pretty mind-blowing up. How long did you spend just reading for this book and how much of it did you read in the original Chinese as opposed to in English translation?

Megan: I was worried you were going to ask me that. I went into the reading and researching process with great intentions of reading as much as I possibly could in Chinese. And just very quickly fell to my knees and realized I just couldn’t get through it all, especially if I wanted to cover I guess the range and diversity I really wanted to include in the book. So I would say, in the end, quite a small number of books were read in Chinese and they were exclusively the ones that I couldn’t get hold of in translation in any form here. And then the rest I take my hat off to the very talented translators who’ve done a really amazing job. It’s a labor of love for so many of them. And I relied heavily on their work.

Kaiser: Yeah, there’s just a set of wonderful core translator. So I’m doing everything from worker poetry and worker fiction, like Eleanor Goodman is doing to all those people who are associated with the Paper Republic in Beijing.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: And then, old stalwarts like Howard Goldblatt, right?

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: There’s a great list of the translators that you tip your hat to, toward the end in your acknowledgments. And it’s a real who’s who.

Megan: I’m completely indebted to them. I can’t lie.

Kaiser: Yeah. But you did have to read all of this stuff on the web, though, that I can’t imagine has been translated yet. That must have been…

Megan: Well, I mean, you’d be pleased to hear that some of it has been… You can go and check it out. There’s also some very devoted translators. Some of them I think are extremely young, who do very bad translations of arguably quite bad novels. But you do still get a sense of the thing that is being read and written online.

Kaiser: Well, maybe the badness of the translation is an accurate reflection of the quality-

Megan: Or I’ll just blame the translation.

Kaiser: Yeah. I feel a little bit better because I would have struggled. I struggle to read in Chinese anything longer than a couple of pages. When you look at… It strikes me always when I look at some of the literature that emerged in the ’80s and the ’90s, especially. When you look at the literature of the May Fourth era, all the way up to your era, and you compare it to the literature that we’ve been talking about just now; the Yan Lianke’s and Mo Yan’s and stuff, it’s hard not to see a lot of continuity.

There’s still a lot of cultural self-flagellation, I guess you could call it. It’s there. It’s loathing and contempt directed in a lot of the celebrated modern literature that we’re familiar with at what these writers perceive to be fundamental flaws in the Chinese psyche, or in the Chinese character. It seems that May Fourth casts a really long shadow. I mean, does it strike you the same way? And what do you think this says about Chinese society about critical Chinese writers, that these themes seem to be so persistent?

Megan: I don’t think that the writers of the ’80s and ’90s are so preoccupied with the inherent flaws of the Chinese character or society, even though they are very much preoccupied with them. But I do think the thing that links them or the shadow that has been cast is the need for writing to serve a purpose, that it carries this moral burden almost to reform society, to change it, to expose what is problematic in people’s thinking, or how society is structured. So I agree there is a degree of continuity in that sense.

But I also think, especially with writer like Yan Lianke and Yu Hua, also someone as singular as Zheng Xuan, I don’t think they feel like they are standing on the shoulders of giants. I feel like they have spent a long time honing their craft, figuring out what they feel about their past, about China, about society itself. And their work is entirely unique to them really. I think the problem seems to be more for the generations after them who are really struggling to find a voice in this new ascendant China.

Kaiser: Yeah, that’s interesting. It feels like prior to Yan’an, prior to the 1940s, there was that real sense of that burden. You had to write for national salvation or national enlightenment. You had to do all that soul-searching and to not have taken up that mantle would have just marked you as frivolous. To have not written politically during the years of high Maoism, would have been not just dangerous, but it would have been dismissed as bourgeois and frivolous again. And then in the aftermath, once again… I mean, if you’re not writing to the devastation culturally left by those years of high Maoism… I mean, what you’re saying is that now that they don’t feel burdened necessarily by politics, they’re struggling to find a voice. That’s tragic, huh?

Megan: I have really sensed that reading various blogs and interviews on things like China Writer, which is one of the state-backed sites for young writers. And a lot of them when they’re asked about what characters their fiction is they feel like they don’t have anything important to say. They feel like because they haven’t suffered in the same way as their parents, because they have had a better life, they somehow are struggling to find a subject and arguably their own subjectivity while writing.

And I get the sense that’s something they’ve slightly inherited. They’ve been told these things and it’s part of being, I guess, loyal to that discourse, that they need to not be thinking about themselves, they need to be thinking about the fate of those worse off than them. Which, incidentally, I think, is a really interesting influence on Chinese fiction, which we don’t really have in the West in the same way, just this imperative to think about the fate of others.

Kaiser: Yeah, that’s maybe why so much of it focuses on the subaltern then.

Megan: Yeah, I think. And it has since May Fourth. It’s always been about the subaltern in some sense, as it was under Mao. I think the ’80s weren’t about this. I mean, I think everybody felt like they were themselves the victims of very difficult times and needed to sublimate those experiences or grapple with their own actions, maybe. But I think now because there is this narrative of economic uplift, young people are really struggling to justify ever writing about their own life. And I think that there’s something quite sad about that.

Kaiser: So I wonder if they feel that pressure, not just domestically, now just within the Chinese writerly milieu, but also, maybe, from outside of China. I mean, because I can’t help but notice that there’s an expectation that we in the West tend to saddle Chinese writers with as well. There is a conventional wisdom I would think. By my lights, it’s something like, “The only literature worthy of the name is the stuff that is overtly critical if not flat out dissident,” right? And then this claim that, look, there simply isn’t any decent literature coming out of China right now because censorship.

But what you’re painting is a picture of… I mean, it’s different, though. I mean, it doesn’t seem like necessarily censorship is what’s keeping them from writing, although I’m sure it’s a factor. How would you tackle that? Do you feel like with this book, you’re able to transcend the Western gaze, as it were, and manage to talk about what China is reading or what China’s writers are writing on their own terms?

Megan: Yeah. I mean, that’s something which I think I’ve had to grapple with quite a long time myself. I remember, first going to China, I think, in 2012, in my capacity as a journalist, and interviewing a ton of writers in a big room. And I just instantly felt like I needed to ask about censorship and to ask them about how they deal with it. And it felt like a brave thing for me to do. And the minute I did it, I just felt a bit rubbish about the question. I felt quite ashamed that I’d asked them.

Kaiser: But in your defense, that should be a factor. I mean, it’s something –

Megan: It’s a huge factor. I really do think it is one of the biggest challenges China faces for also thriving cultural scene. I think what was shameful for me was that I had just walked in assuming that I was there to bring this topic to the table and finally have some constructive debate about censorship or something, quite ignoring the fact that Chinese writers have lived with it in various degrees for many, many decades. And they know what they’re dealing with and they have all chosen very different ways of dealing with that side of things. Some very inevitably, some quite depressingly and obediently. But I still feel like it’s their choice how they want to deal with those ultimately “sets of notes” in terms of how they engage with the artistic process, and I just felt a little bit cheap, I think. I haven’t asked that question again. And lo and behold, the writers who want to talk about it, they bring it up pretty quickly, so.

Kaiser: I imagine. It’s not just in film [EDITOR: I meant literature], though. I feel like in other genres of Chinese art… I remember, in the mid 2000s, talking to somebody who ran a major European Film Festival. He was at my house. We were having drinks, so a little gathering of people. And he told me flat out that they were only interested in basically films that couldn’t be screened in China. And I said, “Is that just the schtick? I mean, is that what you do? You go…” That would have made sense to me. But now he says, “No.”

He thought that it was not possible for a film to have literary merit or merit as a film unless it were explicitly banned in China. Do you feel like that is still there in western treatment? I mean, let’s go back and talk about when Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize in literature. He came in for a real beating internationally by a lot of people who thought that just because he was part of the literary establishment that therefore his writing couldn’t have merit.

Megan: Yeah. And I think also a lot of people came to his defense for the same reason. But it was a difficult thing for a lot of people to understand. He’d recently just copied out the Yan’an edicts about how writers should write for the Party and things in public. And he compared censorship to being akin to airport security or something. I think what people had misunderstood was that Chinese writers operate in a multifaceted way a lot of the time, and they have a political public persona, and then they have their arts, which often has no relation with the person. So there’s a big separation between the art and the writing.

I mean, I remember Shen Keyi defended him and said he’s being attacked for his politics, not for his writing. They’re not the same thing. And that’s quite hard for us to understand. I think we increasingly actually read things knowing what we think of somebody’s politics. And if we find out that their politics aren’t to our taste, it’ll definitely influence how we read their work. And in China, I think a lot of people keep a very clear distance between those two things.

Kaiser: Yeah, it’s becoming increasingly less tenable to do that in the United —. I mean, just I think of J.K. Rowling, for example. Nobody really reads her stuff the same now. I mean, everyone’s looking for the anti-trans subtext in everything she writes now.

Yeah so you have a real fondness for Yan Lianke. He’s the author of books like Serve the People, and The Day the Sun Died and Ding Village. Those are his personal books outside of China. What is it that you love about Yan’s work and what would you recommend? Where would you recommend somebody start with his fiction?

Megan: Yeah, the reason I like… It’s quite hard to articulate why I like him so much. I just am constantly drawn to the worlds he creates. The Four Books is a particularly brilliant example of his… He calls it mythorealism, his type of genre. It’s set in a reeducation camp and it’s a Rashomon-style approach to events. Within the reeducation camp, there’s a biblical narrative. There’s an author who tells two stories. One where he’s dubbing in all of his inmates. The other where he’s trying to make amends for being such an asshole to them all and then a really petulant child who’s a stand-in for the leader.

The thing that’s so captivating about his work is… This may not appeal to a lot of people, but I feel like it’s really imbued with an illuminating sadness. It’s deeply humane and beautifully written. And also, he creates worlds which I haven’t come across in any fiction, anywhere else in the world, really, for many other writers. It does feel unique to China. It feels unique to Chinese history without in any way caricaturing it or turning it into something that’s stereotypical in any way.

Kaiser: So The Four Books, I haven’t actually read that. Is there an English translation of that?

Megan: Yeah. As far as I know, it’s translated by Carlos Rojas —

Kaiser: Oh, Carlos? Yeah, he lives up the street from me.

Megan: Oh, really? He’s an incredible translator. And he’s a very good fit, I think with Yan Lianke and always just… Anyway, it feels like the right fit for Yan Lianke.

Kaiser: Oh, Carlos, and Eileen, if you’re listening, apologies for that. In atonement I’ll go out and buy a copy right away.

I’m wondering though, do you ever feel like we cut Chinese writers too much slack? I mean, let’s be honest here. Half of the literary devices that they deploy — the parables and metaphors — are just so on the nose sometimes that they would be dismissed with bored eye rolls by the New York Editor where they’re submitted by an American writing in English. I mean, how are they able… Because this is a constant feeling that I have. It’s like, “Really, this is your metaphor?” I mean, it’s like, “Could you just not put this gigantic sign blinking and pointing at it”?

Megan: Who are you thinking of in particular?

Kaiser: It’s just so many times that I’ve seen this. Okay, we know Ma Jian. We can talk about Yu Hua. We can talk about lots of them who do this.

Megan: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think Ma Jian is an interesting one in that I think I get the sense and I say this respectfully that living abroad for a long time, he’s been held captive almost by the need to be so overtly political. He really wants to take aim. And also, I think, that’s often what happens when you’re at a distance from China that you start seeing it more and more metaphorical binary. Well, I don’t want to put words in his mouth. I really love his fiction, by the way. In a way his metaphors don’t bother me. They feel suited to how angry he feels, and how he… And then I think, in terms of the eye-rolling stuff, I definitely come across it with a lot of the younger writers I’ve read who are just forgivably trying to cut their teeth and figure out how to write and stuff. But I never really feel it with the writers born in the ’50s and ’60s.

Kaiser: No, that’s good. This is a very subjective thing obviously. I was just wondering about your opinion. I wonder whether that might be the case for somebody like Ma Jian writing from outside of China. I’ve often felt like I’m really impressed with the subtlety that you have to use when you’re writing in China under the gaze of the censors, to get away with it. I mean, maybe it forces you to be a little less direct, and on the nose.

Megan: Definitely. I think there’s also something about being on the nose, which isn’t… It’s certainly not true to what life is like living in China. You can’t just say whatever the hell you want. And so to write something on the nose is also not in many ways representative of that experience.

Kaiser: So it’s got to be liberating to do that.

Megan: It’s liberating to do, yeah. But I also think that there is… It’s I guess, the artistic process where you are trying to, through perception, insight, and through a long period of time, you spend years writing a story, find acceptance for the truth of things in an interesting way, rather than just stating them outright.

Kaiser: Yeah. And that’s what writing is all about.

Megan: So that’s what many of them do. That’s what writing is all about.

Kaiser: So it feels like and, I think we are all in agreement here that politics is inescapable when writing about Chinese literature. And in part, that’s because in China, the party since the Yan’an Forum in ’41, has made it very clear that it’s got a purpose. And this has been revived now under Xi Jinping. I mean, they’ve re-emphasized this once again. Is there any literature that you looked at for this book, where you felt that you as a critic could relax the political muscle a bit and just take it in without the political framing? I mean, surely there are genres that get consumed in China without the reader being forced to confront the politics, right, maybe?

Megan: Yeah. I mean, yes, in that, if you look at the vast web novel industry, it’s the biggest –

Kaiser: And we will. We will.

Megan: We will. It’s almost defined by how apolitical it is. There’s nothing that can peg it to real life really, to real experiences, to real people. It’s pure escapism. And then I think that the question of whether something can not be political is an interesting one. And I don’t honestly know the answer. But I do think in a country where there are imperatives that you have to write on behalf of others or on behalf of the collective, on behalf of the party, individual viewpoints or a unique subjectivity is just by virtue of itself political and that is what makes it interesting as well.

Kaiser: The decision to be apolitical is itself political.

Megan: And I think that the government feel that too.

Kaiser: Yeah, I know they do.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: So I think being able to write holy separately from politics is really only a privilege that writers in the prosperous liberal states of the West have really enjoyed traditionally, and Japan or in places that enjoy political freedoms. We were talking earlier, and you said something interesting that I thought might be worth unpacking a bit here. How this is changing also in the Anglophone world, especially in the years since Trump and Brexit since 2016. Can you talk a little bit about that idea to expand it? What did you mean by that?

Megan: I think I’ve really felt as have a lot of people, not saying anything new, that since the Trump administration, since Brexit, the rise of right-wing populism in various European countries, there has been a very uncomfortable awakening for a lot of people that we’re not on the same page as each other. There isn’t an agreed reality. And I think even the New York Times ran a piece this new year — “America’s Reality Crisis.” And I think, I remember reading Salman Rushdie saying that he thought people wrote magical realism when there was a sense that nobody was on the same page. And I think Chinese writers have been doing that for a very long time. There’s been a very clear master narrative. And then, in my experience, most literature, even if it’s trying to adhere to that mass narrative doesn’t do it because it’s impossible when one person is just hammering away and writing something, that other stuff comes out. But China has a lot of very interesting, strange, wacky genres. And I think we will increasingly see that as our previously agreed narratives are being often quite widely deconstructed. They’re being reinterrogated, rewritten and people won’t be able to just write middle-class family stories anymore and feel like it’s part of contemporary society in the same way.

Kaiser: Megan, we were chatting the other day, and we both went down this memory lane, this little nostalgia trip about the literary scene in Beijing, let’s say where we both lived for a very long time. For those of our listeners who weren’t lucky enough to have been able to experience that firsthand, and I was only glancingly familiar with it myself being a literary tyro. Can you paint a picture of what it was like in Beijing in the literature scene, in the aughts?

Megan: Oh, God, I wish I was more embedded into it than I was. Obviously, it began for me with hanging out a lot at The Bookworm.

Kaiser: Oh, God, I miss The Bookworm.

Megan: I know. But I didn’t speak great Chinese and they offered bilingual talks, and I got to know a lot of writers and writing through there. And also, I love the people who worked in the shop. They would recommend really interesting books for me. And then I think by extension, there was a sense that a lot of the bookshops that were flourishing in various cities, actually, not just Beijing, were full of real literary enthusiasts. And I spent a lot of time, more and more time, in book stores, when I was there. They used to be the ones that would sell knockoff DVDs of arthouse movies, which I would stock up on back in the day.

They tended to also overlap with a lot of the artists who were working out on… I forget which ring road now, but we’d go to their openings and things. There would be various writers and books being sold there at the same time, and it genuinely felt more exciting being there than being here. And I missed it definitely.

Kaiser: “Here” is London, right?

Megan: Yeah, I shouldn’t say that. We have a flourishing publishing scene here, but just it felt manageable and exciting at the same time which-

Kaiser: I know what you mean. Exactly.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: And I love that overlap. I mean, people who were in film, playwrights, musicians, visual artists, all gathering. It was a real scene in the truest sense.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: Those were the days. Megan, as much as I enjoyed what you wrote about the more writerly writers, I have to say, the chapter that really grabbed me, that really fascinated me — well, fascinated and horrified me, was your chapter on web fiction. I mean, it’s something that seems pretty unique to China. I mean, certainly at scale, even if some of the genre conventions are borrowed from other East Asian countries, what should we know about Chinese web fiction, about the economics of it, about who produces it, who consumes it? And how the government reacts to this?

Megan: I think internet fiction started off as a very niche and exciting thing with Murong Xuecun and his writings from the earlier stuff, yeah. And Anni Baobei and people like that, but they quickly fell by the wayside. They were writing things that weren’t welcome and they took up writing elsewhere.

Kaiser: Imagine Murong Xuecun writing something that’s not welcome.

Megan: Exactly. Yeah, they unfortunately lost their footing pretty quickly. And it was just replaced by this, who would have thought it, but growing and vast industry of fantasy writers who churn out sometimes 10, 20,000 words a day. And people would check in and read each chapter each day in a kind of modern day Dickensian serialization process. And they have absolutely exploded, there’s now 24 million titles available-

Kaiser: My God.

Megan: 430 million active readers.

Kaiser: That’s a third of the population of China. That’s insane.

Megan: Apparently, again, who knows, but as you probably seen on community to just see people scrolling through these novels. And I can’t believe how popular they are really, not only because they’re generally not great but because people are in this sort of digital age, people are still reading, people are still tuning in everyday to devour stories and that’s kind of impressive as well.

Kaiser: Yeah.

Megan: But I think they’ve become this sort of clash of this main fault line in China between government and big business. And they seem to represent that big clash where it’s a way for young people to make money if their IP is sold for one of these TV shows, or an anime, or manga adaptation. But as a result, they’ve become really popular and the government can’t stand it. So there’s two big titans fighting it out to control the content now.

Kaiser: Who are those? Are they just the industry itself? Or is there one or two companies that are taking up the banner?

Megan: Yeah, so Tencent who own the most of the online reading platforms now –

Kaiser: Wenxue Cheng.

Megan: … and the government. Yeah, exactly.

Kaiser: I’m curious though, in the United States or in the English-speaking world, we’ve seen things, we have a gigantic fan fiction phenomenon and it’s related. A lot of this stuff starts off as fan fiction based on a favorite anime or manga series based on characters from a beloved… wuxia or xianxia kind of novel. We’ve seen this in the States, he had like all this Harry Potter fan fiction. And he had, of course, the success of books like 50 Shades of Grey which started off as Twilight fan fiction, I suppose. I’ve never actually read it all. I mean, it sounds horrifyingly bad.

Megan: I’ve never read it either.

Kaiser: But it’s like this phenomenon happening just every day. Every day some new piece of web literature is picked up to be turned into a movie. I know my sister-in-law is a — was a very successful screenwriter, who wrote a lot of well loved Chinese television series. But now she says basically they’ve been replaced. I mean, all they do all day is scour the web and see what’s trending in this free-spending demographic, and they don’t know that they’ve got a sure-fire hit. I mean, that’s depressing. I mean, it can’t be doing good things for literature.

Megan: No, I don’t think it is, unfortunately. And it’s also not doing great things for the writers themselves. I think they are all insane. There’s so many of them and they’re all given these incentives that they might get snapped up. But as a result of trying to keep eyeballs, to keep people reading, they are reduced to either having to pander to this very active audience who are telling them what they want to happen, or plagiarism, copying other stories, just to literally get the words out each day. And so they really do all share quite unique algorithmic traits that feel really predictable, and a product of it being turned into a sort of grotesque business. It’s just a huge industry, a free-market fiction which is about economic leniency and still kind of avoiding all cultural taboos or restrictions. Although, not so much anymore but anyway-

Kaiser: Yeah, maybe that is the bright side of it, though, the silver lining as it were – that there’s a lot of queer themes in it. There’s a lot of, what they call, BL or— that’sthe English word — Danmei fiction. Can you talk about Danmei fiction and what role that plays in this larger genre of internet fiction?

Megan: Yeah. Danmei, it’s boys love fiction, written mainly by female writers. And it came over from Japan, I don’t know when. Very popular there but it’s become I think the most popular form of romance in China for young girls to read. I remember going to Hong Kong to host of Comic-Con exhibition. I was trying to get some manga to read and some comics, and I think three girls told me, “The only romance you need to read about is Danmei.” Like, that’s what all girls want to read. And the theory is that it reveals that a lot of girls are still feeling dissatisfied with the role that women have to play in society. And they love reading about two lovers who are completely free of any kind of incumbent obstacles that face girls.

Kaiser: Ah, interesting.

Megan: I mean, the other thing worth mentioning is the minute you read it or you watch it, you just stop noticing that it’s BL. It’s just a romance. It’s a story that you’re just in.

Kaiser: What about… I mean, but there isn’t as much lesbian-themed fiction. I mean, there’s some, but it doesn’t seem to be nearly as popular. What do you suppose is the reason for that?

Megan: Yeah, I think it’s because lesbian fiction in particular seems to be very quickly censored and banned. I think there’s a few male writers who have really wanted to include lesbian love stories and that’s what’s got their novels taken down. Whereas there’s a quite famous writer called Priest and her novel Guardian — or Guardians? — was about two super-sleuths who were in love with each other. And for the TV show, they just got a straightening up and it was turned into socialist brotherly love. So there was something which has become a bit of a like joke. Now, you just have homoerotic undertones but it’s all about commitment to friendship and loyalty to each other in the mode of socialist heroes. So I think as long as there’s no sex at all, the government has been happy with close male relationships in the way that, for some reason, two girls is absolutely not okay.

Kaiser: I remember 20 years ago or so, I was approached by the director Stanley Kwan from Hong Kong and I ended up subtitling a wonderful film that he did called Lanyu. But it turns out… I didn’t know this at the time, but that was web fiction originally.

Megan: Oh, really.

Kaiser: I think it was. I mean, it was… I can’t remember the name of it now, of the original novel, but it was like the first big sort of gay love story out of China.

Megan: That’s not Beijing Comrades?

Kaiser: Yeah, it is. Beijing Comrades. That’s what it’s called.

Megan: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Kaiser: Because it had its origins as a sort of underground piece of web fiction.

Megan: Yeah, I didn’t realize it started off as web fiction. I know it was… The author is still unknown, still anonymous. And I think, Stanley Kwan, didn’t he think that it was Wang Xiaobo?

Kaiser: Yeah. He thought it was Wang Xiaobo. Yeah. Which makes sense to me. I mean, if people don’t know, he’s a wonderful satirist who got really popular in the early ’90s, I guess, The Golden Age, The Silver Age, these books…

Megan: Yeah. But I think a lot of people thought that it might have been written by a sympathetic female friend. So that’s the other theory of why Danmei been so popular in China is that a lot of girls are very close friends with young gay boys who have not been able to express themselves and they’ve written these love stories on their behalf. That’s one of the theories.

Kaiser: Those are the old… I really enjoyed subtitling as a gig because if you just timed it, you knew when all the directors of indie films would be desperate to get their films into competition. Invariably, they had already asked some friend of theirs, a Chinese person who spoke some English, to do the subtitling. And then, they showed it to an English or American friend and they were like “ghastly.” And they immediately had to scramble to find somebody who do subs quickly. And so you could charge them kind of extortionate rent for it.

Megan: Sounds great.

Kaiser: That was a great gig. Let’s move on to science fiction, which is I think is fantastic. I was commiserating with you not long before this conversation about how cagey certain science fiction writers are about talking about the Chineseness — I ask everybody, what, if anything, makes Chinese science fiction distinctly Chinese? Then nobody seems to want to answer me. Can you give it a shot? Is this something that you think is common themes in Chinese science fiction?

Megan: Yeah. I think we might be in some agreement in that. And it’s really pegged to Liu Cixin, who sci-fi is truly sort of hopeful and optimistic. It’s epic but it’s devoted to an exploration of the stars essentially, and seeing what’s out there and embracing the unknown. I think the other thing that makes Chinese science fiction distinctive really is it’s, as far as I can tell, quite an elite genre, and that it’s written by very highly-educated, impressive scientists and engineers, and physicists. And they’re all using very exciting cutting edge ideas, but writing quite often sort of Ray Bradburyesque and simple tales about what the future might hold. And with that comes a sort of a genuine degree of optimism about where technology might take us, and AI, and deep learning programs. And even imagining, and not in a negative way, the possibility that machines could possess more humanity than we do, and that could be an exciting thing. And I don’t really feel — so much Chinese fiction is really dystopian and strangely, a lot of its sci-fi isn’t.

Kaiser: That’s fascinating. Yeah, I’ve made that observation too, about the lack of really heavily dystopian science fiction coming out of China. I mean, the laugh line I get when I talk about this is that, we’re in our Black Mirror phase here in the West and China is still in its Star Trek phase, to boldly go where no man has gone before. That’s fantastic. I do agree with you. A long time ago, I interviewed this philosopher named Anna Greenspan. I think it was like in 2013 or 2014. She’s Canadian academic. She had written this great book called Shanghai Future: Modernity Remade. And she talked about how Chinese people seemed to have just a different posture toward futurity than people from North America or Western Europe. And since that conversation, I mean, the profundity, the truth of what she had pointed out has just gotten clearer and clearer to me. I’ve come to believe that it makes a significant difference in the way that people interact with technology. The way they imagine the future, obviously, is represented in sci-fi. And science fiction, it’s about imagining the future and the technology so integral to it. What about, is there a Chinese politics in Chinese science fiction? In other words, have you read books where China as a nation-state or China as a civilization or whatever is projected into a future? And what kind of roles that it has in that imagined future?

Megan: The first person who springs to mind is Bao Shu, who’s he started off writing Liu Cixin fan fiction.

Kaiser: Ah. Interesting.

Megan: But he’s one of the few writers to have got into a bit of trouble with the stories he’s written. One of them is called, I think, Songs From Ancient Earth, where he imagines a future where the universe is… I think, there’s a spaceship has crashed on a distant star and it’s been indoctrinated with red songs. The only thing that remains from Earth, they’re all kind of computers, as far as I can tell on this spaceship. All that remains of Earth is red songs, and, red culture and red… And he sees that as a damning thing. We can’t –

Kaiser: Remember I was saying about other nose metaphors, right?

Megan: Yeah, exactly. There you go. but I think one thing that… Again, and I’m drawing on writers that people probably know quite well, so Hao Jingfang and Liu Cixin. They tend to think about the world not in terms of just trying but as a world having to come together through something. It’s quite in keeping with the official Olympics message, but I think they do dare to imagine it. It’s not something that… They don’t seem to be the kind of the arch-nationalists and patriots that want to just see China taking over the world. They’re just interested in what kind of partnerships different cultures will be making to bring the world together.

Kaiser: That in itself is very hopeful.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: I like that. So it’s such a short book. I mean, there are things that we haven’t talked about yet. I would love to talk a little bit about, maybe, the crime and legal genre fiction, sort of the equivalent of the John Grisham or what have you. That there are probably lots of other genres and certainly lots of writers that you would have included had you been given more space. Before we talked about what you had left out. Let’s talk about a couple more things that you did include, including these different…I would say genre fiction is really important to understanding a culture. I mean, if I were looking at the United States from some imaginary distant perspective, I wouldn’t think it would be fair if all we read was like Donna Tart and Don DeLillo. We would have to read Danielle Steel. We’d have to read John Grisham or… I was horrified. I was looking at best-selling authors in the United States over the last 50 years or something. And it was — I was , Dan Brown it’s like, “Ugh!.” But –

Megan: Yeah, don’t check bestseller charts for hope about the arts, I would say.

Kaiser: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, I was actually doing so that… Because curious. Like, if you’ve done the same exercise from China looking at the United States you would have been selected. But you did include some shorter fiction writer. Can you talk about, like I said, the legal genre. And some of that has been really successful like, In the Name of the People, became a wildly popular and very good, I have to say, television show.

Megan: Yeah. So I think Zhou Meisen wrote In the Name of the People as an online novel, started off writing it. And it was tied in with the anti-corruption campaign that was launched. I forget when it was, you’ll know better than me.

Kaiser: 2013, 2014.

Megan: There you go. And did you watch the TV show?

Kaiser: Yeah, I did. I did.

Megan: Yeah. I think the thing that really seemed to capture people’s imagination was they really wanted to see corruption being tackled head on. And it was really pleasing, and really exciting to see the justice system cracking down on these things, which they felt was pervasive and also untouchable for many, many years. And I think a lot of people see it as the government kind of playing a bit of a blinder because it looked like they were finally allowing corruption narratives to be screened or published. And it looked like they were the ones who were kicking its ass, basically. But as you say, it was also really enjoyable and a lot of fun for people to watch, probably because they needed it. It was like a form of catharsis, I think. Yeah, that was a huge hit a few years ago.

Kaiser: Yeah. What are the other let me surprised genres that are big. I mean, here, I know what to expect when we walk into a bookstore. I know there’s going to be the kind of hard-boiled detective novel, there’s going to be the bodice ripper romance novels, the Harlequins, whatever. I mean, there’s pretty established genres. There’s going to be the fantasy and the sci-fi. And we all know the difference between fantasy and sci-fi. What is there in China that we don’t have in the West?

Megan: Yeah. So there’s… I mean, I actually didn’t really include much of this and I didn’t read much of it is workplace fiction which is about the kind of cut-throat office politics of people straight out of university trying to get ahead in the office. And it’s really, really popular. People find it very, I think, consoling to sort of one get tips or just find ways of at least acknowledging that these things happen and it sucks.

And then there was a really fantastic novel called The Civil Servant’s Notebook, which was translated by Eric Abrahamsen. And it’s really funny. It’s a mayoral politics, basically. And it has Staplers talking to staples, philosophizing about the nature of who’s better off. And how you get ahead, is by shouting thief and stealing something from someone’s pocket. And it’s just really kind of down and dirty and gritty. The government kind of waved it through as an example of how you shouldn’t behave. It wasn’t seen as brutal satire of what does exist. But it’s a really brilliant book. I’m not sure how popular it was, but I would hope it was very popular.

Kaiser: Workplace fiction, I’ve seen… I know, there was a book called Du Lala or something like that.

Megan: Yeah.

Kaiser: Right. Right. That was made into a film by Xu Jinglei, who’s a very, very talented actress and director called Go Lala Go!, or something like that.

Megan: That’s right. Yeah.

Kaiser: Is that what we’re talking about. Is that’s what workplace fiction?

Megan: Absolutely. Yeah. That’s you’ve hit the nail on the head.

Kaiser: Oh, okay. Yeah, I wonder, do we have that in… And I said I’ve never read anything like that, but I mean, Nine to Five I suppose-

Megan: Yeah, it’s kind of Ally McBeal.

Kaiser: Oh, yeah. Yeah. There you go.

Megan: … kind of thing or that sort of stuff. It feels quite similar to that.

Kaiser: Yeah. Oh, great. Yeah. So it’s not entirely alien.

Megan: No.

Kaiser: Yeah, fantastic. So what about stuff that you couldn’t include that you would have really loved to? I mean, because you… This is only 100 pages and that is, I should say, because of this particular imprint, its Columbia Global Reports, which — they’re slim little volumes. I’ve read a few of them and they’re very, very good. What would you move up? Who would you have included if you had been given more space?

Megan: There’s actually just a lot of young writers that I think are really impressive, but because of, I guess, the limitations as you say of the length, they just didn’t find a natural home in many ways. There’s a whole new generation of surrealists who are really exciting and interesting. And I couldn’t… I just… It almost feels quite appropriate that they didn’t fit into the book itself that they are a kind of niche group of writers. But I think they are representative of, I guess, how young people are trying to grapple with this idea that they don’t know what to be and they don’t know where to be and –

Kaiser: It’s kind of a common condition for young people.

Megan: Yeah, it is. I remember reading Xu Zhiyuan, who owns a One Way Street Books. But I remember him saying he really wished that he could still come across young poets who just felt lost, and this is a couple of, maybe 10 years ago. And I think there’s just a lot of them now. A lot of young people a bit lost and a lot of them are sublimating that and writing really kind of great fiction as a result. And then there are kind of other writers that… There’s an absolutely amazing writer called Qian Jianan, who I think is actually now studying at Iowa doing an MFA.

Kaiser: Oh, it’s good program. Yeah.

Megan: It’s a great programme and she’s an incredibly talented writer. She wrote a book called People Who Don’t Eat Eggs. Hasn’t been translated yet, but I absolutely loved it. And in the end, there just wasn’t enough space for me to devote what I wanted to to it. But I would highly recommend people read a lot of her English. She writes in English also and she’s a very, very illuminating writer. Just check her out online.

Kaiser: Yeah. Although as a person who eats too many eggs, I don’t know if I could… That’s fantastic. Megan, what a treat it’s been to talk to you. I mean, I highly recommend this book for anyone who wants to plunge into the world of literature in China. And again, I think it really ties in with this thing that we’ve been doing about thinking about China, because I think the lens of humanities is one that we do not apply often enough when we think about China. And it’s super eye-opening. And it’s a fun and very, very easy read. And you’ll learn a ton. So congrats on the book which is, again, it’s just out this week in the U.S. In the UK we have to wait another couple of months. So thanks so much. There are also, by the way, chapters in there that we didn’t get to, for example, about Tibet and Xinjiang-themed literature or Mongolian-themed. There’s a whole kind of scathing takedown of a lot of the stuff that — what’s the Wolf Totem guy?

Megan: Jiang Rong.

Kaiser: Yeah. Jiang Rong. Yeah. But yeah, it’s a fantastic little read and I highly recommend it. Speaking of recommendations, let us move on to recommendations. But first, a quick word from our sponsor. I mean, remember that the Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project. And if you like the work that we’re doing with Sinica or with any of the other shows in the network, the best thing you can do to support us is to subscribe to The China Project ACCESS, our daily newsletter. It’s just a fantastic compilation with commentary from our author Jeremy Goldkorn and his crack team. So check it out and you’ll be doing a great service if you subscribe. So always really good discount rates available, if you look. So let’s move on to recommendations. Megan, what do you have for us.

Megan: The first thing I’d like to recommend is a book by Yiyun Li, who most people have probably heard of. She’s a Chinese writer who moved from China to the US, I think in the late ’90s, to study as an immunologist. And she turns out she’s one of the finest writers in English anywhere in the last 20 years, I would say. So any of her novels or short stories are worth reading. But the book I want to recommend is Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in My Life.

And it’s her… It’s a kind of love letter to reading that the authors that have got her through periods of depression, but also made her the writer that she is. But I also think, for me, it was a really important book because it was also about the importance of reading out of your own cultural sphere. The many Irish writers, she loves William Trevor and John McGregor, but also people like Turgeynev and things. But she’s such a kind of incredible writer, penetrating and rationed. And it’s unlike anything I’ve ever read really, and so I would highly recommend people to check it out. And I have one other.

Kaiser: Yeah. Yeah. Please, go.

Megan: The New Zealand singer-songwriter, Aldous Harding, who has a new album out, and I haven’t listened to that yet. But her last three albums are really odd and really brilliant. And you could check out her music video The Barrel just for a little idea of what she’s like, but I think she’s great.

Kaiser:

Oh, fantastic. That sounds like I’ll definitely check that out. So my recommendation is When You Finish Saving the World by Jesse Eisenberg, who’s a very talented writer, actor comic. He was in The Social Network. Y’all know, he played Mark Zuckerberg in that. In this it’s a weird thing. It’s an Audible Original, is kind of medium, is kind of difficult to describe. He plays a guy named Nathan who’s a slightly non-neurotypical brilliant guy who’s a new father. And he’s having a great deal of difficulty connecting emotionally with his infant son, Ziggy. The first section of, let’s… I’m going to call it an audio epistolary drama. So Nathan’s recording a kind of diary into his iPhone, that his therapist has asked him to do, just to record his thoughts into his iPhone and send them along. So in these audio missives we learn all about his relationship with his wife, Rachel, who is a very different person, kind of a moral crusader, do-gooder. Then it jumps forward suddenly to the year 2035. And we hear from his teenage son, this kid Ziggy. And it’s funny because the world that he builds… Now, he’s not talking to an iPhone, he’s talking to an AI counselor during these sessions that he’s been assigned to complete because he’s physically attacked another student.

And then he creates this whole very believable social media world and world where people are creating music and selling it to… He keeps talking about… He’s got a big audience in Lijiang, China in Yunnan. It’s very funny. He’s like a singer-songwriter. But also he’s a jerk in a lot of ways. He’s like nakedly capitalistic and stuff, and doesn’t get along with his parents. But he has this whole vocabulary of oddball, new 2035 teenage slang. And the actors really great this kid named Finn Wolfhard who was in Stranger Things.

And then there’s the Rachel section, so it’s three parts. And then Rachel section is, she’s voiced by the actress in the film Booksmart, Kaitlyn Dever. And she’s recorded into a cassette recorder back in like the early 2000s in tapes that she sent to her pre-Nathan boyfriend who is serving in Afghanistan. And it starts off as a sort of manic comedy. Jesse Eisenberg, he’s very, very funny. By the end of it, you realize he’s actually brought it all home and gotten pretty profound and sentimental but has let you connect dots. It’s not… It’s just the pieces fit together really nicely without being wedged in.

It’s s not a perfect performance, but it’s damn good and it’s really original. I’ve never come across anything quite like it. And the voice actors are just… They have to be heard to be believed they’re, they’re amazing. They’re so talented. So that’s my recommendation. Apparently, they’re making a movie out of it which I think is I can safely assume it’s going to ruin it, because this is definitely meant to be consumed in audio form. It’s called, When You Finish Saving the World. And it’s actually free if you’re an Audible subscriber, so check it out. Megan, thank you so much.

Megan: Thanks for having me. I really enjoyed myself.

Kaiser: Yeah. And I can’t wait to see what comes out of you next. Would do have something great… I mean, you just published this book, so I shouldn’t ask you that. But you had a book-

Megan: Yeah, it’s the killer question. I have no idea.

Kaiser: Good, well, relax. Take a vacation somewhere and enjoy yourself. You’ve earned it. You’ve earned it. Hopefully, we’ll have you back on again soon for whatever. Well, I’ll come up with some excuse because it’s been such a pleasure.

Megan: Well, thanks for having me, Kaiser.

Kaiser: The Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project and is a proud part of the Sinica Network. Our show is produced and edited by me Kaiser Kuo. We would be delighted if you drop us an email at sinica@thechinaproject.com. Or just as good give us a rating and review on Apple podcasts as this really does help people discover the show. Meanwhile, follow us on Twitter or on Facebook at @supchinanews. And make sure to check out all the shows in the Sinica Network. Thanks for listening. We’ll see you next week. Take care.