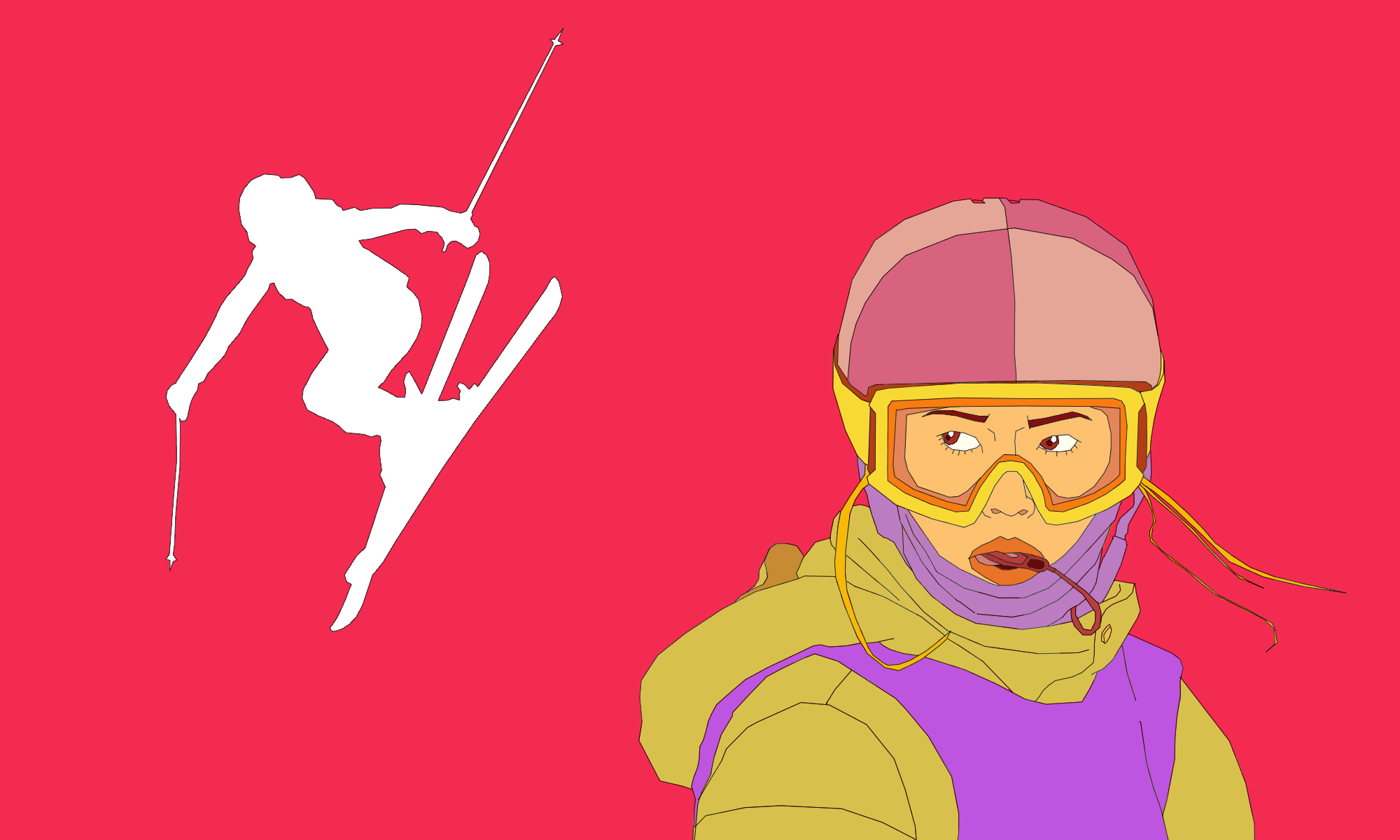

The geopolitical-fueled reactions to freestyle skier Eileen Gu — who has been marked as a traitor and claimed as a hero — reveals a lot about how society sees multiculturalism and identity.

The rise of 18-year old San Francisco-born freestyle skier Eileen Gu (谷爱凌 Gǔ Àilíng) has caused considerable debate and hand wringing in the media, most of which surrounds her 2019 choice to represent the People’s Republic of China at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. But my younger sister and I have known a different Eileen, beginning earlier, when she was an up-and-coming athlete with only 30,000 followers on Instagram (she now has 1.1 million).

Back then, Gu posted daily stories of her life; she was an avid journaler and her cursive print would fill the pages of her notebook. If you zoomed in and squinted, you could make out the aspirations and vulnerabilities of this teenage athlete. My sister and I meticulously sent each other the latest news about her: from the “Everyday Eileen” Red Bull mini-documentaries to articles about her X Games victories. When Gu got into Stanford and cried, we all celebrated, even though we had never met her.

Part of our fascination was that we had never seen a girl like her so visible in the media. Gu was fluent in both Mandarin Chinese and English and was actively immersed in both cultures (and Gen-Z senses of humor). She spoke of self-care, positive body image, and passion. We knew she was going to become a big star someday, yet it also gave us both anxiety to watch it unfold.

You can understand why. Accompanying the recent influx of media coverage — from Time Magazine, ESPN, the New York Times, Bloomberg, etc. — came accusations and criticism. Headline-writers capitalized off her controversy to build engagement: Gu apparently “ditched” the U.S., while mainstream papers openly questioned why she still “lives there” (um, because she has a home there?). Other publications got weird. As the commentary piled up, I couldn’t help but notice a conspicuous lack of Asian-American and American-born-Chinese perspectives.

While many of the challenges that Gu faces as an Olympian and preternaturally gifted competitor are unique, American-born Chinese (ABCs) like myself have dealt with questions about our identity and loyalty for years. Will she be embraced or will she be shunned? Curiosity and hope about the “Eileen experiment” (as I call it) are deeply rooted in these frustrated feelings and other childhood experiences. Eileen Gu maybe doesn’t want to comment about it, with all of her words being dissected by societies on opposite sides of the world, but ABCs like my sister and I can.

Loss of innocence

At the age of five, I started attending Sunday Chinese school, weekly two-hour language classes to learn how to read and write in my parents’ native language. I loved learning. I loved communicating my ideas with more people and laughing in a completely different style of humor. As I grew older, the weight of the language changed. The U.S. economy slowed as China’s soared, and suddenly people were speaking of this new global “superpower” in terms of a geopolitical rivalry. Every time the hard “CH” sound in “China” was uttered during nightly news broadcasts, I would grow anxious. I learned to brace for the inevitable discussions at the dinner table and rhetoric at school.

“If you know English and Chinese, you can pursue a career in U.S.-China relations. You can become the bridge between two cultures,” my mother said. Yet she also told me that because of the way I looked, Americans would never see me as “one of them.” She passed on her hopes for peace, but it came tinged with her past trauma and experience of racism and discrimination and a desire to find a home.

Imagine being 10 years old and being told that you, as an individual, have to embody all of this. No pressure. My father would say that I was “overthinking” if I spoke about this anxiety. My white peers at school could not empathize.

Growing up in Richmond, Virginia, I recall feeling a distinct form of ostracism. Perhaps my predominantly white classmates had no malicious intent, but I was clearly viewed as “other.” Discussions about communism would yield not-so-subtle glances from classmates. My sister, six years younger than me, once praised China’s high-speed railway infrastructure, only to be admonished by her AP history teacher for having any “allegiance” toward a country like China. My sister and I did not have an “allegiance” — but words of praise for China were seen as a traitorous act. They didn’t use the word traitor — as many have against Eileen Gu — but their implication was clear: it’s us or them. The teacher told my sister that he did not believe in “hyphenated” identities.

When I watch Eileen express herself in Mandarin, I see so many similarities between my code switching and hers. Multiple things can be true. She can be thinking strategically while also loving the people and cultures that she grew up with.

Similar to Eileen, I spent most of my middle school summers in China. I had childhood experiences — and nostalgia for those experiences — that my peers would never understand. But Eileen would. Relatives in China told me that I could not comment on Chinese national policies because I was American. Any critique resulted in a comment about how I was an outsider, that I could “never understand.” They assumed I had an iPhone because that was an American phone (despite the fact that I could not afford one). If Donald Trump said anything about China — which he did, a lot — I was asked to explain. It felt burdensome to always be asked to defend some government’s actions. I found myself repeatedly reassuring people that nuance did exist. I did not ask for this responsibility.

To be an American-born Chinese (even of Han ethnicity, while with its privileges) can also mean losing one’s innocence early on. It is to hold a weight of responsibility for decisions that were never yours. Eileen Gu has nothing to do with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Peng Shuai, Hong Kong, or Xinjiang, but she will be asked to talk about them.

People somehow cannot dissociate a government from its people and culture. And more and more, it’s people like us who have to answer for that ignorance. It’s tiring.

Conditional belonging: exceptionalism or bust

Gu’s socioeconomic privilege and fluency in Mandarin, with a charming Beijing accent, has opened doors for her. No question she has capitalized on her natural talent, good looks (there are quite a few people in China who are obsessed with her mixed race, specifically the fact that she’s white and Asian), and now Stanford-credentialed work ethic. She is nearly perfect and lauded as a poster child for her excellence.

I worry about her — because what if the adoration she receives is conditional?

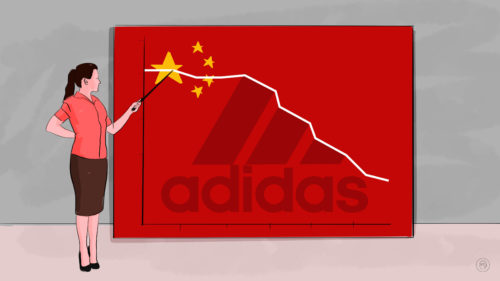

Another California-born Chinese athlete, figure skater Zhū Yì 朱易, a.k.a., Beverly Zhu, received harsh criticism on Chinese social media after falling during the Olympic team skating events. These comments spiraled into contempt for how the athlete, who switched countries in 2018, was chosen over native-born talent. Zhu’s lack of fluency in Mandarin Chinese also did not help her case. Gu Ailing is beloved, but Zhu Yi is shunned. Ailing is welcomed home, whereas Zhu Yi is questioned. If an ABC succeeds, they will be claimed, like a commodity. If an ABC fails, they will be discarded.

Our identity is assessed on a variety of factors — speaking the language, retaining aspects of culture — that are often outside of our control. ABCs are deemed “whitewashed” and “banana” when we don’t fit the conventional definition of “real Chinese.” But it takes two to tango, and many parents decided at an early age to shelter their children from racism by speaking English at home. The fact that Yan Gu, Eileen’s mother, maintained her daughter’s connection with her heritage is still scrutinized. She’s accused of creating an environment where Eileen somehow could not make her own choices, as if she were brainwashed.

This conditionality is something many ABCs are familiar with, and it stems also from experiences of being labeled forever foreign in the United States. As Gu revealed to Time Magazine in an interview, during the COVID-19 pandemic when anti-Asian bigotry was on the rise, she feared for grandmother’s life.

I see these feelings bubble to the surface when ABCs succeed. When Nathan Chen won the men’s figure skating individual gold medal, tweets addressed the irony of Americans cheering for someone they also shunned. One mentioned how the Olympics are “forcing Americans to cheer for a dude whose last name is Chen,” and how, after pandemic-fueled racism, that feels like “Asian America’s mic drop.”

But you can’t win. As Americans celebrated Chen, on the Chinese internet, people deemed him an “rh” — 辱华 rǔ huá — a term literally meaning “disgracing China,” used as internet slang to brand him a traitor. You see, more than a year ago, he had made a comment alluding to China’s human rights record.

I honestly believe that if Eileen Gu were not this good — she won gold in Big Air last week, added a silver in slopestyle earlier this week, and has a chance for another medal tomorrow in her favored event, the freeski halfpipe — Americans would never hear of her name. Twitter trolls and Tucker Carlson would not label her a “traitor.” People suddenly care only because of her gifts. Athletes switch countries all the time, and are also actively recruited by national sports federations to do so. (I certainly haven’t seen former Senator Claire McCaskill tweeting about the white athletes on China’s Olympic hockey teams, anyway.) It is the loss of talent that makes people mad. What does that mean then when your love is only conditional upon a good performance?

Identity defined as a binary

“When I’m in the U.S., I’m American, but when I’m in China, I’m Chinese,” Gu often says.

It’s 2022. We know gender is not a binary and that many identities in our lives exist on a spectrum. Yet I’m still being asked, “Are you more Chinese or more American?” as if there were a universal definition of what it means to be “Chinese” or “American.”

Watching the social media debates about Gu’s citizenship status has been painful. Her capacities as a human with emotions and agency are secondary to everyone else’s opinions about geopolitics. The perception of loyalty, of patriotism, of identity in itself is based upon an idea of nation-state. Why? Because that is how, regardless of whether we grew up in the U.S. or China, we have been indoctrinated to organize our world. The Olympics, for all its idealism and love of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” reinforce the idea of national identity. That is the way in which our competitions are funded and structured.

For many ABCs caught up within the hellstorm of geopolitics, our joy is policed. For Eileen to find a way to negotiate a new norm feels like a form of resistance.

People cannot fathom that I can appreciate Chinese culture while also being critical of the CCP. The number of times that I have been asked by someone, from relatives to random strangers, “If America and China went to war, what side would you choose?” is astounding.

I think back to my first lessons about Asian American history in school, focusing on Japanese internment during World War II. We see people with complicated identities as an “other,” a potential national security compromise, a traitor. We see these humans as a threat defined only through the small minds of powers that be. Othering people during times of geopolitical tension is part of civilization, but people caught up in the act are always blindsided by the way they repeat history.

Being an individual

People debate whether Eileen Gu is a pawn. The truth is, we are all pawns and have always been in the eyes of governments and corporations. People love to frame Gu’s choice as financially motivated, yet never question the earnings of other Olympians. American snowboarder Shaun White’s net worth is $60 million. Just one year ago, the Tokyo Summer Olympics hosted Kevin Durant, who makes $75 million per year, and Naomi Osaka, who made $55 million in endorsements in the previous 12 months. If Gu chooses to advance her career and wealth, that is her choice.

To inspire millions, Gu works within a system that forces a choice. People are borderline obsessive at how the Chinese government may potentially be granting people like Gu the privilege of two passports (there is no confirmation that she has renounced her American citizenship) because these benefits do not extend to everyone. Sure, we can express contempt for her elite privilege, as other women are seemingly swept under the rug within larger existing structural inequalities. But why are we hating the players rather than the game itself?

When asked about her decision to represent the P.R.C., Gu told the Associated Press: “I’ve gotten a lot of hate, a lot of people saying ‘It’s a question of loyalty and which country she likes more.’ It’s really not. It was really a big thing between the impact I would be able to have and what I’d be able to do with skiing.”

I’m sure that Gu is very well aware of what her choice can mean. She is aware of the platform she has. That is why she speaks out about racial injustice in the United States. She is aware that if she speaks about Chinese politics, her platform will vanish. We can speculate all we want about her motivations. But what we know for certain is that she’s a girl with big dreams and the belief that she can inspire millions. No other American-born Chinese has the world’s attention as she does.

When I watch Eileen express herself in Mandarin, I see so many similarities between my code switching and hers. She makes people laugh. She makes people feel inspired. Multiple things can be true. She can be thinking strategically while also loving the people and cultures that she grew up with.

In the Youku documentary about her, My Legacy and I, Gu says, “The most important thing for me in life is to find something you love, and enjoy it.” As she has expressed in other interviews, she is proud to represent her sport and herself.

For many ABCs caught up within the hellstorm of geopolitics, our joy is policed. For Gu to find a way to negotiate a new norm feels like a form of resistance.

Why do my sister and I care about Eileen? We care because she could be that exception that we hope will become the norm. And because within her, we see bits and pieces of ourselves. We wonder if she will speak out about human rights abuses amidst censorship, because we ourselves have tried to bring up these topics to our elders, unsuccessfully. We wonder if journalists will stop asking her to talk about “balance,” with the hope that people will also stop asking us. The nation-state in sports gives an athlete both freedom and restrictions. We sit and wonder if she will be able to achieve what we ourselves feel is often unattainable because of geopolitics: just being seen as an individual.