This Week in China’s History: March 18, 2002

On this week in 2002, a man died in La Rochelle, France. He was 106, especially impressive considering he had lived through the First World War and fought in the French Army in the Second. Married with two children, he worked as an electrician and a crane operator, and in his later years was visited regularly by the mayor as one of this port city’s most esteemed citizens. It was a remarkable life for any number of reasons, not least of which was that he had been born, in 1896, in China’s northeast Shandong province.

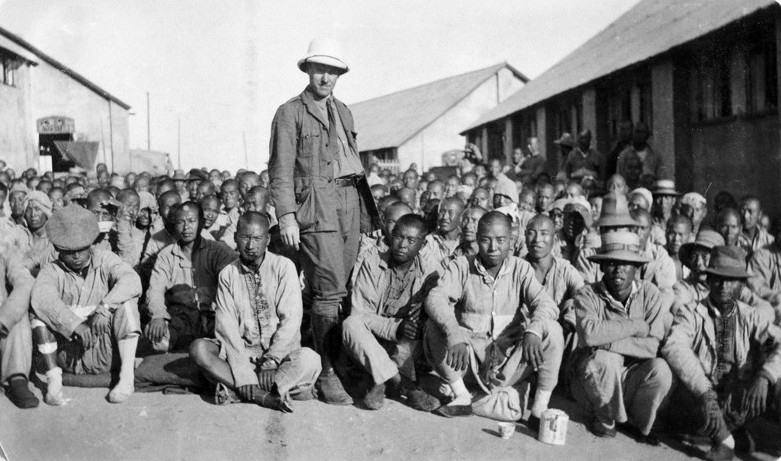

Zhū Guìshēng 朱贵生 was the last surviving member of the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), a force of some 140,000 men who served in the Allied effort in World War I. He signed a five-year contract in the summer of 1916, one of the first Chinese to do so. The story of the CLC, told concisely in Mark O’Neill’s Penguin Special The Chinese Labour Corps and in more depth in Xu Guoqi’s Strangers on the Western Front, sheds light on much about China’s struggle for acceptance in the Western world order, as well as that of individual Chinese in Europe.

When the first world war broke out, China’s republic was less than three years old. War among the European powers threatened the new government that was struggling to find its footing. Germany and Britain both had colonies in China. Russians dominated the northeast, centered on their semi-colony Harbin, and the French always seemed ripe for expansion from their claims in the southwest, bordering their colony in Indochina. The Chinese government was eager to avoid becoming a battlefield for other countries’ wars, as had happened in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. With this in mind, the Republic proclaimed its neutrality.

But neutrality was not the only approach. Some in the Chinese government saw opportunity in choosing a side. A first suggestion, to ally with Britain to take the German colony at Qingdao, was rejected — dismissed by the British and opposed by the Japanese, who took the city themselves early in the war. And it was the perception of the Japanese threat that drove China to make another offer to the Allies, but China’s military capacity made entering a war as a full-fledged ally implausible.

Instead, in a proposal devised by advisor Liáng Shìyí 梁士诒, Chinese laborers would go to Europe to support the war effort. Europeans wouldn’t fight alongside Chinese troops as equals (many soldiers from European colonies fought in the war, as colonial subjects), but would tolerate Chinese support staff. Neither the French nor the British wanted to involve China at all, but as the war wore on, the need for additional manpower became acute. The European powers all expected a short, glorious war; no one was prepared for the devastation. Within months, if not weeks, it was clear that new weapons were not just killing men, they were devouring an entire generation. As Xu put it, “The French government realized that it might soon go bankrupt in human resources because it simply did not have enough men to replace the dead and injured.” As early as March 1915, the French considered accepting Chinese laborers to work on roads, but misgivings within the military leadership delayed the decision. Finally, that fall, Chinese officials expressed to the French that they could provide up to 40,000 workers for France, and in January 1916, a delegation arrived in Beijing and began recruiting laborers for France.

So it was that Zhu Guisheng, and tens of thousands like him, was recruited to go to Europe.

China wished to remain neutral to avoid hostilities on its own territory. Obviously, China’s government could not directly support the Allies and maintain its neutrality, so a “private” company was established that would facilitate the recruitment and transportation of the men. This Huimin company set up offices around the country, but most of their recruits came, like Zhu Guisheng, from Shandong (British and Chinese officials believed that men from the northern provinces were stronger of stature and better accustomed to the climate they would encounter in Europe).

The Chinese government insisted that the laborers not be used in combat operations, that they receive the same rights and conditions as their French counterparts, and that Chinese diplomats could be sent to ensure that their treatment was in accordance with these terms. The contracts stipulated that the Chinese men be civilians, working of their own free will, and forbidden from performing military operations (to preserve Chinese neutrality). Allowances to the workers’ families back in China were guaranteed in addition to the wages paid in Europe. Beyond that, the contracts differed by country. When the British began recruiting a few months later, their terms were not as favorable: contracts were for just three years and paid 1 franc per day (below the wages of British workers), with labor expected 10 hours per day, seven days per week, with only “due consideration for Chinese festivals” in terms of days off.

On July 12, 1916, the first Chinese laborers boarded the (ironically named) SS Empire. Empire was among three vessels that set out from Tianjin that month, bringing more than 5,000 recruits to Marseilles. Zhu Guisheng was perhaps among 1,400 men on a boat that left Qingdao for France in August. The new arrivals boosted French hopes for their war effort. Soon, officials were making plans for as many as 10,000 Chinese to arrive each month, and 100,000 by the end of 1917.

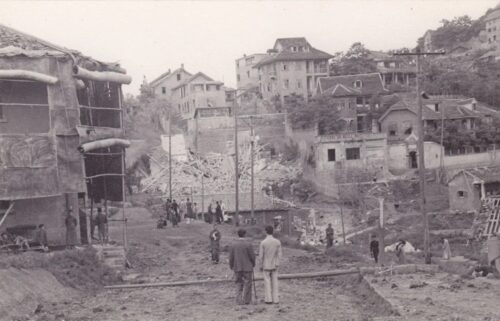

These estimates turned out to be too sanguine. About 40,000 laborers were brought to Europe by the French. The initial optimism was tempered by an incident in the fall of 1916 in Tianjin that nearly provoked an anti-French boycott in China, and a tragedy in the Mediterranean in the spring of 1917 when a German U-boat sank the French transport Athos, killing more than 700 Chinese.

Most laborers employed by the French, like Zhu Guisheng, found themselves far from the front lines, replacing French workers in factories, building and repairing roads, and doing other manual labor. Chinese recruited by the British faced more dangerous, and more militarized, work, working closer to the front lines and in direct support of combat operations. Hundreds, or more, died in gas attacks, artillery barrages, and aerial bombardment. Historian Xu concludes that while it is impossible to know exactly how many Chinese died in the Great War, his reading of the evidence suggests “that it is safe to say that around 3,000 Chinese lost their lives in Europe or on their way there due to enemy fire, disease, or injury.”

When the war ended, most laborers remained in France for the remainder of their contracts, either 1920 or 1922, depending on whether they were recruited by France or Britain. Notably, the French contract gave workers the option of remaining in France after the end of their contract, while the British insisted that the Chinese be repatriated after the war’s end, largely at the insistence of the labor unions who had opposed the arrival of Chinese workers altogether.

Zhu Guisheng was one of about 2,400 Chinese who were still in France in 1924, and one of just two who lived until 1989, when they were awarded the French Legion of Honor.

By overthrowing the Qing monarchy and installing a more “modern” form of government, many Chinese reformers expected to join the “family of nations” that Europeans and Americans put forward as the model for a civilized world. The Chinese plan to provide labor in Europe during the Great War was part of the bargain — along with more transactional goals, like forgiveness of the indemnities European states had imposed on the Qing, and the recovery of German-held territory in China. (Those last two failed, at least in the short run.) But, as Chinese laborers observed and endured the horrors of the Great War, one of the lasting impacts of the Chinese Labour Corps was to undermine the very idea of “Western civilization” as a model that China, or anyone else, should aspire to.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.