This Week in China’s History: March 20, 1913

The revolutionaries who brought down the Qing Dynasty envisioned a Chinese republic that would be welcomed into the family of nations. Just months after the revolution broke out, the last Qing emperor abdicated and a provisional president was installed. A legislature had been elected.

The man who more than any other individual embodied China’s hopes for a democratic, republican future was on his way to Beijing, riding an electoral wave that had seen his party claim a majority in the new assembly. At Shanghai Railway Station, he and a group of colleagues prepared to travel north to the capital.

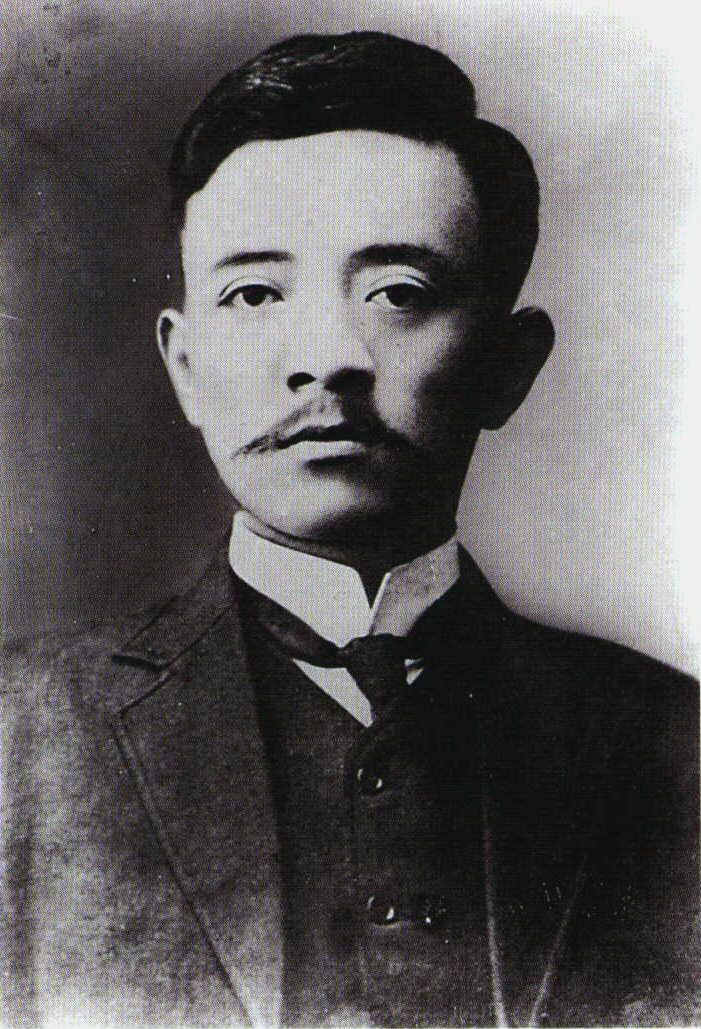

Sòng Jiàorén 宋敎仁 never reached Beijing. Before he could even board the train, he was approached on the platform and shot twice at close range. Rushed to a nearby hospital, he survived for two days before succumbing on March 22, 1913.

The idea that Song Jiaoren represented a democratic future for China may seem unlikely. Sun Yat-sen (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) gets the headlines: a charismatic, Western-educated revolutionary who is revered as the “father of the nation” (国父 guófù) on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. Intellectuals like Liáng Qǐchāo 梁启超 and Kāng Yǒuwéi 康有为 are deeper cuts on the album of Chinese reformers. Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) ascended to lead the Republic of China to be one of the “Big Five” allies of World War II. And of course Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 stood famously atop Tiananmen and proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic.

But Song Jiaoren might have been the last, best chance for a functioning Chinese republic. At least the last for a long while.

Song was born in 1882 in Hunan and privately educated. The civil service examinations were still the idealized path to a prestigious career, for those with means, but Song rejected them and chose to focus instead on contemporary world events. By the turn of the 20th century, he was enrolled in Boone College in Wuchang — an episcopal boarding school and an ancestor of today’s Central China Normal University. There — where in 1911 the uprising that would overthrow the imperial system began — he first encountered anti-Qing revolutionaries, working closely with Huáng Xìng 黄兴 and becoming a founder of an anti-Manchu (and anti-Russian) group called the Huáxìnghuì 华兴会. In the wake of two failed plots against Manchu officials, both Huang and Song fled the country, joining a community of progressives and revolutionaries in Tokyo.

In Japan, Song and Huang began working with Sun Yat-sen, throwing the support of their Huaxinghui behind Sun’s new organization, the Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance). Bringing together numerous revolutionary groups, Sun’s Revolutionary Alliance was the umbrella organization that focused on overthrowing the Qing and replacing it with a Chinese republic.

Song took part in several failed attempts at revolution, but when the dynasty did fall, in the wake of the Double 10 Revolution of 1911, Song was at the center of the new republic. He drafted the provisional constitution. But he soon found himself, like the rest of the Tongmenghui, in opposition to the president, Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凯. Yuan had basically strong-armed his way into office with the threat of violence. Sun Yat-sen had prestige, charisma, big ideas, and connections, but not the weapons he needed to maintain leadership. Yuan took power and looked to consolidate it.

But there was the question of elections. The republican government was not just a president: elections were to be held, for a bicameral legislature, and the role of a prime minister would, in theory, be as important as the president. When elections were called, Song Jiaoren led the process of, first, turning the Tongmenghui into a political party, now called the Kuomintang (KMT), and then of organizing the election campaign. Song was tactically skilled and organizationally brilliant, and a much more practical leader than Sun Yat-sen. Many people saw the threat that Yuan Shikai represented — he was no democrat, and preferred that no elections be held at all — but Song was more effective than most in opposing the president (who would later show his true colors when he declared himself emperor). Song shunned bribes and threats, and allied with smaller political parties as the election campaign wore on. In the end, the KMT won pluralities in both houses of the legislature.

Here it is important to remember that Song was no saint, and that the dream of a republic could be cynical and calculated just as much as it could be idealistic. Only about 10 percent of China’s population was enfranchised, and Song played to the male, educated, wealthy electorate. Socialists and feminists were important parts of the KMT coalition, but Song jettisoned planks calling for socialism and women’s suffrage, knowing that those issues were unlikely to attract voters.

The compromises had done the trick. Though not in the majority, the KMT was the largest party, and thanks to Song’s deft politicking, he was almost certain to be elected prime minister. From that position, he could oppose Yuan Shikai and move the republic along a more democratic tack. It would be a difficult fight against entrenched interests and the considerable personal power of Yuan, but the pieces were on the board.

Democracy did not fit with Yuan’s plans, though. Rather than political chess, he chose murder.

Shanghai’s criminal underworld was a political machine unto itself, and the boundaries between it and “respectable” politics were porous. Yuan reached out to Yīng Guìxīn 应桂馨, the leader of Shanghai’s Green Gang mob (who had, to demonstrate the point, been a member of Sun Yat-sen’s presidential guard) for help with eliminating his rival. On March 20, Ying’s designated killer, Wu Shiying, approached Song on the platform in Shanghai and shot him with a pistol. Thirty-six hours later, Song was dead.

The assassination of Song Jiaoren had many more victims than just the would-be prime minister. Wu Shiying was arrested soon after the murder and died in prison a month later. Ying Guixin was murdered in unlikely fashion — by two sword-wielding assassins in a luxury train car — less than a year later, apparently to cover up connections to Yuan Shikai. The greatest victim of all might have been China’s democracy. On his deathbed, Song wrote a telegram to Yuan — the man responsible for his murder — and implored him, “I humbly hope that your Excellency will champion honesty, propagate justice and promote democracy.” Needless to say, Yuan did not, and died less than three years later having outlawed opposition political parties, declared himself emperor, and seen China’s fragile republic come apart at the seams.

But this is not meant to be a “great man” theory of history. Song Jiaoren had a difficult task ahead of him if he made it to Beijing. If China’s parliament were to enact reforms, it would have relied on the work of institutions and processes, and hundreds if not thousands of men and women. Conversely, Song’s death did not doom the republic to failure. There were other opportunities. But without question, the options open to China’s democratization diminished on that March morning at the Shanghai railway station.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.