Shannon Bufton, a pioneer in Beijing cycling, forges ahead

A former competitive-cyclist-turned-bike-maker seeks to solidify his legacy in the kingdom of bicycles.

Shannon Bufton and I biked the wrong way down a one-way lane near Beijing’s Bell Tower. We dodged cars, baby carriages, and a homemade flatbed truck pulled by an antique motorcycle until we came to a coffee shop camouflaged in the gray, stone alley.

He leaned his kick-around-Beijing bike on the wall, an untouched early-90s-era Rossin. He didn’t bother locking it, so I didn’t lock mine. He took a seat by the window where he could keep an eye on the street. Even in a city with more than a million surveillance cameras, bikes and scooters still sometimes disappear.

When Bufton moved here in 2009, he’d find mounds of the iconic Flying Pigeon bicycle piled behind apartment blocks, collecting dust. “No one cared about those bicycles. Everyone was buying a scooter. Or if they could afford it, a car.” Bikes were an old-fashioned way for getting around. But then, as Beijing’s middle class burgeoned, cycling as a recreational pastime gained ground, and Bufton, a former competitive-cyclist-turned-bike-maker and route planner, found himself in the right place at the right time.

With his wife Zhào Lǐmàn 赵礼曼, Bufton founded Serk in 2012, a company that designs and builds titanium bikes for China’s frontier. “When we started, there was no one out there, like there were hardly any cars,” Bufton said. “You go on a ride in Pinggu or in Miyun” — districts northeast of the city center — “you’d encounter two or three cars in a 70-kilometer ride on a Sunday morning. And there were zero other riders, like zilch.”

Bufton began organizing trips to the mountains. He pioneered routes.

“At that stage, Miaofengshan” — west of city center — “was the place that the Chinese riders would go to,” Bufton said. “And that was the first place that I started riding, too, when I came to Beijing. So if you went to Miaofengshan there’d be a few riders on the climb. Now I guess there’s hundreds that go up every weekend. I haven’t been up in a while because it’s too crowded.”

Bufton, 45, is at the forefront of a cycling revival in Beijing. He’s “iconic,” said Harry Li (李陶 Lǐ Táo), a TV commentator. “He brought new kinds of ideas,” said Fù Yìqún 付轶群, a longtime Beijing cyclist. His bikes are a “ridiculously comfortable ride,” according to influential writer and cyclist Andy van Bergen.

With a new brand space opening later this month, Bufton is in Beijing for the long haul. But with previously empty mountain roads now teeming with cars and bicycles, and heart disease mostly keeping him off his bike, he’s setting his sights on new frontiers — and fending off a claim that’s downplaying his legacy as one of Beijing’s route pioneers.

I met Bufton nearly two years ago on a Serk ride. We left Beijing by bus in the morning, my beat-up mountain bike looming over the lithe road bikes of the more experienced riders.

Most of the riders were expats like me. We drove a couple of hours west to Fangshan, to a route Bufton calls the Beijing Stelvio. I was on the C route with the other slow riders, with Bufton our leader.

The first 17 kilometers was an ascent leading to a series of steep, looping switchbacks. I struggled on my heavy bike, while others in my group were two or three loops ahead. They waited for me at the top, where Bufton led us on foot through a gap in the fence.

On the other side was our reward: a descent that curved for kilometers next to faded brush that had blanched into a uniform brown landscape, on a road so new that cars weren’t allowed on it yet. Pure. Ecstasy.

Bufton had spotted this descent during a climb as he was taking photos. “I saw there was another twisting road down below into the valley and I’m like, ‘What the hell is that road?’ And I could see that there was some construction happening there. And then I came back a couple months later and it was tarmacked. It never opened to the public. But our cyclists made some gaps in the fence and worked out how to get through.”

At almost 17,000 square kilometers, the municipality of Beijing feels endless. Beijing is larger than the countries of Lebanon and Luxembourg combined. Almost two-thirds of it is thinly-populated mountains — some as high as 2,000 meters — that run from the northwest to the northeast of the city’s dense center.

Sometime in the last decade, governments paved the dirt roads that connected the villages that dot the mountains. Bufton estimates that a thousand kilometers of new roads have been paved since he’s been in Beijing.

“The roads are like riding on black velvet,” his friend, fellow Australian Brendan Mason, told me. “I can’t think of anywhere else in the world where they’re as good as they are here.”

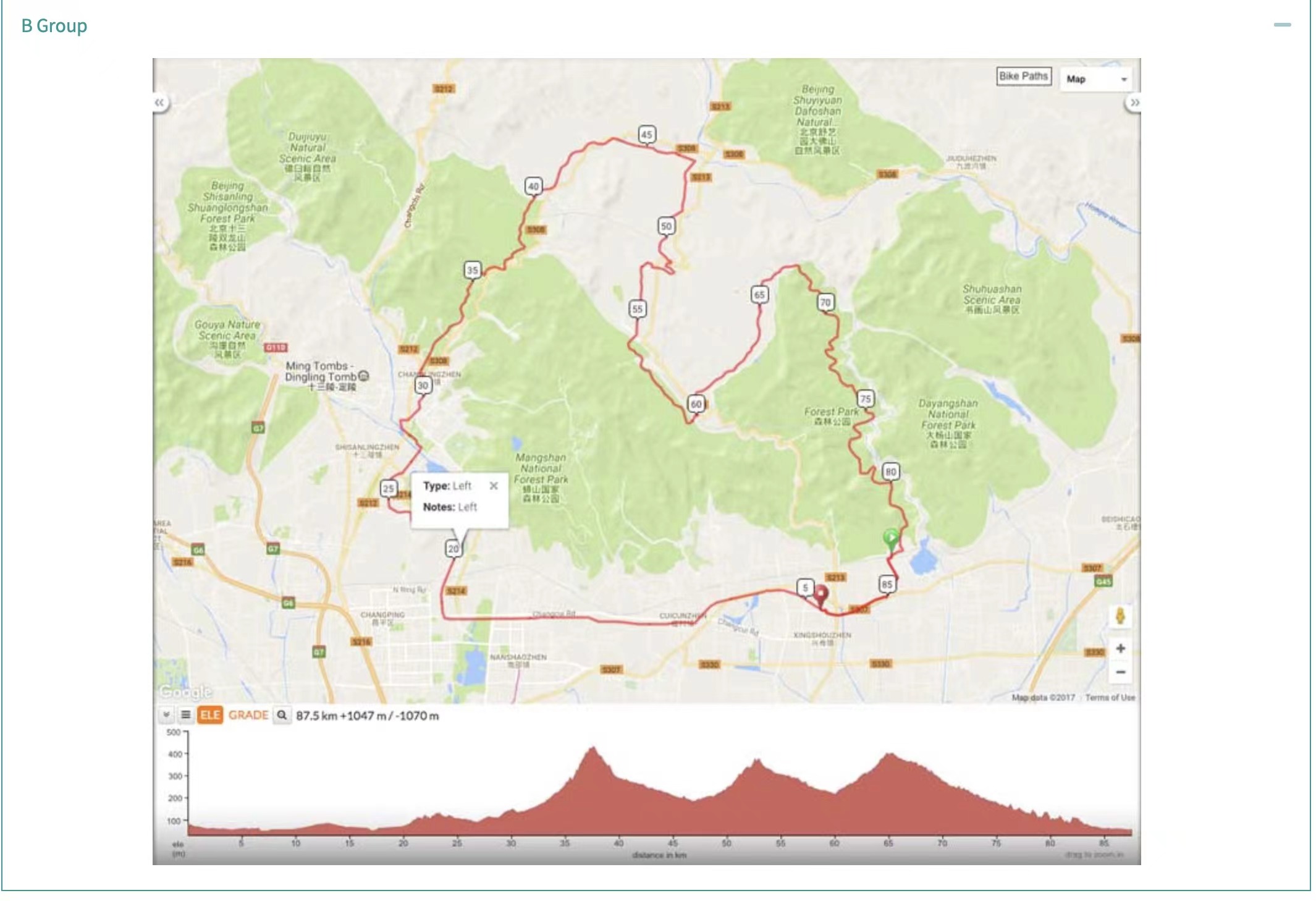

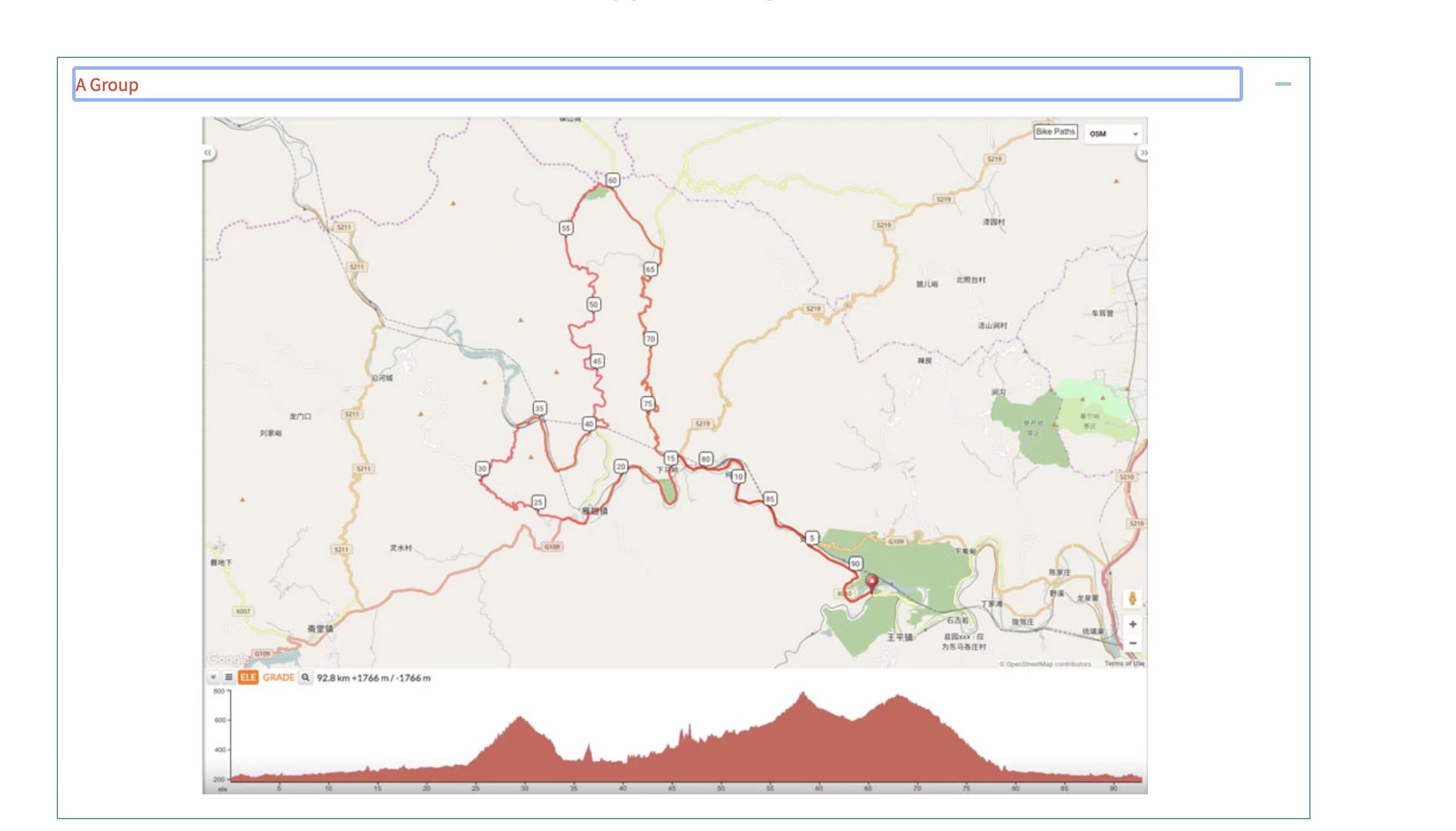

Bufton and his crew at Serk made sense of these roads by riding them, photographing them, plotting them, spending hours on Google Maps to create courses that consider riders’ fitness levels and their ability to tackle steep climbs and hairpin turns on descents, then leading riders on guided trips they probably wouldn’t — or couldn’t — make on their own.

But a prominent local cyclist and route planner says that many of those routes were mature by the time Bufton got to them, and that Bufton’s contribution to Beijing cycling was in conveying those routes to foreign riders. Bufton and other longtime Beijing riders I spoke to see things differently.

Foreigners have been cycling in Beijing’s outskirts for decades. One of the first organized groups called themselves the Mountain Bikers of Beijing, and plied the mountains when they were still dirt roads. Then came another group, Peloton, which had a set of five or so routes that they didn’t deviate from, according to Bufton. “And then I came along at the next stage when Beijing really started to develop the roads, and I started pioneering all the new routes on the new roads.”

But that timeline isn’t universally accepted. Bufton introduced me to Harry Li as “one of the premier commentators in China,” an “early adopter of cycling culture” who has covered cycling around the world. When I spoke to Li, he downplayed Bufton’s role in China’s cycling development.

“For us local riders, we have a lot of good routes around Beijing in the mountains,” Li said. “When I started riding my road bike in 2007, there were some internet forums to share these routes. So I believe when he came to Beijing, there were already many mature routes.

“But the thing is, for those foreign riders, it might be hard for them to get that information. And many of these foreign riders don’t have a car or a driver’s license, so they needed a person like Shannon to organize those events for them to ride into the mountains.”

I told Bufton I found Li’s answer surprising. “That’s actually surprising to me, too,” he said. “We have over a hundred different routes that we’ve ridden in Beijing…the majority of those routes, we” — Bufton means he and his team at Serk — “were the first ones to ride them in that order. Maybe someone rode that road once before. But actually, in terms of the curation of the routes, there wasn’t much of that before, apart from a couple of standard ones.”

It’s hard to find definitive answers online. Strava, a popular app that tracks cycling routes, doesn’t provide information on who pioneered routes. Dongfanghong, the internet forum Li mentioned, is no longer operational, with only a handful of archived pages.

I turned to long-time Beijing riders for answers. Phil Tregaskis, who has lived in China for 20 years and was a member of the Mountain Bikers of Beijing in the early 2000s, said, “Was [Bufton] the only person that set up routes? No. I mean, Shannon didn’t come up with every single route. But he was certainly one that contributed to that. Back in those days, even 12 years ago or so, there weren’t that many local riders on road bikes, for a start. Cycling hadn’t really taken off. Of course the roads existed, but just because the road exists, coming up with the route is something completely different.

“He came up with a series of rides which have become the classics. And a lot of this was really before people started widely using bike computers with maps included in them.”

Fu Yiqun, another longtime Beijing cyclist, told me, “I think part of the routes came from [Bufton], but not all of them.” He said that while Beijing has a long history of cycling, riders didn’t use the routes they’re using now. In terms of GPS plotting, “Shannon did a lot of that. So more and more people have fixed data for certain kinds of roads.”

Why does it matter who pioneered the routes? I don’t think it’s about the money. Serk charges 500 yuan ($78) to book a place on a Serk bus for a local ride, but only 100 yuan ($15) if you get to the starting point yourself. A day before the ride, Shannon sends a file with detailed mapping directions of the route to a WeChat group. You can import the file to your phone using an app like Komoot, or copy it to a GPS device, like a Garmin.

At this point, there are several ways people can bypass Serk. Bufton himself has published several popular mountain routes online, and savvy riders can find more routes on Strava. Ride shares eliminate the need for a bus. “It’s probably not economically viable for Shannon to run buses anymore because you’ve got substitutes, these little guys that are in the Huolala vans that will take you up to the hills for a pittance,” said Mason, Bufton’s friend. “And that is good for the community but not necessarily good for Serk.”

My sense is that this squabble surprises — and perhaps frustrates — Bufton. He believes bikes are vehicles for change, and cycling represents freedom and independence. It’s about pushing his limits and encouraging others to push theirs.

Bufton suggested that seeking credit for the past may partly be about staking out the next big thing in Beijing cycling’s future: gravel riding.

“For people who sort of come along and then just take those routes off Strava…there’s always time that’s spent by the pioneers to make these things happen,” he said. “I guess that’s also what [Li’s] thinking about, because he’s also starting to do some gravel stuff, but we are way ahead of him in terms of routes.”

As for Li, he’s working on a project called Jīng Jiāocūn Cūntōng 京郊村村通, which aims “to discover every village around Beijing,” he said. “With this project I produce videos and introduce new routes, some of those on gravel roads, to the cycling community, not only in Beijing but all around the country. I’m doing this just for fun, and I think I’ll keep doing it in the next few years.”

I left with the impression that both Bufton and Li care about cycling and are excited to share their data with the world. If the next few years is a race to find and curate new routes, Beijing’s growing cycling community will reap the benefits.

Bufton grew up in a small town in Victoria, Australia. “I was the kid at school who was the last one out of the swimming pool and the last one in the cross-country running events. But I found that I was really good at cycling and it gave me the confidence to push myself further and further. And then I started racing.”

At 17, he finished in the top 20 in the state road cycling championships. Then he went to Germany for an architecture study trip. “But secretly I was hoping I could have a crack at racing in Europe,” he said.

It didn’t work out, and he returned to Australia to study architecture and urban planning, eventually working in Dubai and China. On a trip to Beijing, he met his future wife and business partner, Liman.

He made his way back to bikes in China, where he began to build his own brand. “We try to make things as standardized as possible. So if you’re out in the middle of nowhere and a part fails you, you have a chance to get it from a local bike shop.” Reviews of his products are positive, some effusive, such as this one: “I’d quickly fallen for Serk, in equal parts because of the simple, beautiful lines, but equally because of the alignment with Shannon’s sense of exploration, creating new frontiers, and seeking adventure in … well, everything.”

Bufton feels like he’s accomplished all he can in Beijing, and is now looking farther afield. “Our next big thing is to start exploring the gravel roads, which means we need to go a bit farther out of Beijing and into [the neighboring province of] Hebei. Once you get past that Beijing border, it’s a completely different atmosphere in terms of the infrastructure and roads. It’s like stepping back in time 10 or 15 years.”

This time, Bufton said he would share his routes on a website so it’ll be clear who pioneered them and who created the maps. “It’ll be a driver to our website and to our legacy.”

“We are going through that stage now of ‘what do we want to be as a brand?’” he told me. He sees a couple of options: attract new investment to become a bigger brand, or remain a small boutique company with the freedom to take “a day off when we feel like it because the air’s good and we want to go for a ride, and every year we go out and spend a month pioneering a new route and exploring because that’s what motivates us.”

For now, something else has crept into Bufton’s mind: his health. In mid-2020, Bufton began struggling to keep up with the slow riders on club rides. “I thought maybe I was just unfit, but then it started getting worse and worse.”

He was diagnosed with heart disease. He’s had one procedure, and he’s mulling another.

“The smart thing to do if you’re looking for investment is, you don’t publicly say that you are having health issues and that you are considering slowing down the size of the growth of your business,” he said. But he was moving full speed ahead when I last saw him earlier this month, getting ready to move into a new space around the corner from the office and design space he shares with his wife and two employees.

“This is the interesting thing that’s part of the process of pushing new boundaries — people like you ask those questions and then you have to give an answer,” he said. “And that’s when things get solidified in my head. It’s like tossing up all these ideas, and then eventually you’ve just got to move forward.

“And now I just ride my bike to work and back. It’s been really difficult for me to deal with. But it’s also another opportunity, and I’m giving myself time and space to work out what that means.”

“Another new frontier?” I ask.

“Exactly.”