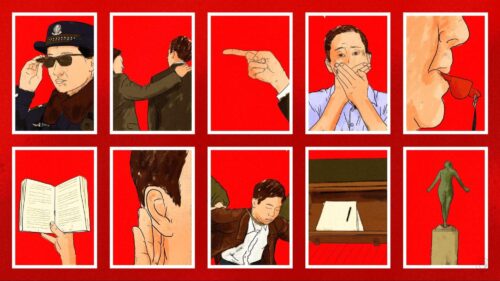

Shanghai residents angered by forced-entry disinfection as Beijing censors WHO director’s comments

The glittering metropolis of Shanghai is entering its sixth week of government-mandated lockdowns as China pursues its COVID-zero strategy despite widespread skepticism about its efficacy and growing protests from exhausted residents.

Shanghai is tightening its stringent COVID lockdown measures, which began on March 27, 2022, contradicting previous promises to ease anti-virus controls. Tensions between the city’s exasperated residents and ruthless COVID policy enforcers have flared again in the wake of a new citywide policy mandating the mass disinfection of people’s homes, with or without their permission.

Over the last few days, videos and photos have circulated online showing teams of hazmat-suit-clad enforcement officers entering households and squirting clouds of disinfectants everywhere, apparently with no regard to how the chemicals might damage or ruin certain belongings. In some clips, a large amount of disinfectant can be seen being sprayed over furniture and other objects inside apartments, including couches, beds, wardrobes, books, and even electronic devices.

According to health authorities in Shanghai’s Huangpu District (in Chinese), a team of 179 anti-epidemic workers carried out the disinfection work at thousands of homes on May 7 after obtaining residents’ permission, and only those occupied by COVID-positive patients were affected.

However, personal accounts posted to social media disputed the official narrative, claiming that consent from residents was not given in many cases and that many affected apartments actually belonged to people who hadn’t contracted the virus, but had been sent away to government isolation facilities because of lockdown policies. Their “unfair treatment,” as critics called it, was the result of a new hardline policy in several parts of the city, where if one person tests positive for COVID, neighbors in the same apartment building are forced to undergo centralized quarantine regardless of their COVID status.

They’ll just break down the door

As part of the policy, before they were taken into quarantine, these residents were asked to give community volunteers keys to their homes, which later came handy for disinfectant workers. But for those who refused to comply, COVID enforcers still managed to find ways to make entry. In one viral post (in Chinese), a WeChat user shared photos of a broken door lock, writing, “Take a look. There’s a neighbor in my apartment building who was COVID-free but still got taken away. He didn’t hand in his key and now his door lock was cracked.”

In response to the complaints about forced entries and possible damage to residents’ property, Jīn Chén 金晨, the deputy director of the Shanghai Housing and Urban-Rural Development Commission, stressed at yesterday’s COVID briefing (in Chinese) that community workers should fully communicate with residents and seek their cooperation before disinfecting their homes. He also emphasized that residents could inform disinfecting workers beforehand of any items “that are sensitive to disinfectants or need special protection.”

But Jin’s promises did little to quell public fury. “This is a performance that serves no purpose other than self-satisfaction. It’s also a violation of personal property rights,” a Weibo user wrote (in Chinese). Others questioned the scientific basis of the measure, as health experts have found that the risk of getting infected from touching a surface contaminated by the virus is extremely low, and that spraying disinfectant is of limited use in stopping the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The subway is closed, WHO is censored

As Shanghai’s mass lockdowns enter their sixth week, the mass disinfections are the latest in a series of measures that have been widely criticized for being too extreme.

But there may be no relief in sight: Top leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 last week vowed to continue the government’s uncompromising COVID-zero strategy despite a significant drop in new infections — the daily number of new cases in Shanghai fell to about 3,000 by Monday, down from a peak of 26,000 in mid-April. But city officials are doubling down on pandemic restrictions after a brief period of loosening up.

On Tuesday, the city of 26 million people suspended service on the last two subway lines that were still operating, marking the first time the city’s entire public transit system was brought to a standstill. Last week, a number of neighborhoods entered a new phase of the lockdown called “quiet period,” during which residents were barred from leaving homes and from having nonessential items delivered.

Meanwhile, Beijing, which recorded 74 new cases on Monday, kicked off another round of three days of mass testing for its 21 million people this week. The city has also locked down a number of apartment buildings and residential compounds in virus-hit districts, shuttered about 60 subways stations, closed schools, and banned dining at restaurants.

For much of the past two years, China’s COVID-zero approach has enjoyed domestic support as new variants of the virus continued to wreak havoc in other parts of the world. But the toll of recent lockdowns across China — including multiple non-COVID deaths caused by medical restrictions, and suffering of people at poorly equipped quarantine centers — has led to an unusual outpouring of criticism.

Outside China, doubts over the sustainability of its COVID policy have become so strong that even Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the head of the World Health Organization, whose views were criticized as too favorable to China earlier in the pandemic, began to waver. At a news conference on Tuesday, he urged China to rethink its severe COVID controls:

When we talk about the zero-Covid strategy, we don’t think that it is sustainable, considering the behavior of the virus now and what we anticipate in the future…We have discussed this issue with Chinese experts and we indicated that the approach will not be sustainable…I think a shift will be very important

His remarks were censored from the Chinese internet just hours after he made them. Tedros’s comments, posted by the official WeChat account of the United Nations, were banned due to what the messaging app called “a violation of relevant laws and regulations.” On Weibo, the UN’s official press account shared Tedros’s comments early this morning, but the post is no longer viewable. As of the time of writing, the Weibo hashtags “World Health Organization” #世卫组织# and “Tedros” #谭德塞# are blocked with images of Tedros’s face being scrubbed from the platform.

Although Weibo posts containing Tedros’s name are still visible, discussions appear to be restricted as most of them are in line with the official response given by Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhào Lìjiān 赵立坚, who said at a daily briefing today that the WHO director’s remarks were “irresponsible.” Some Chinese social media users agreed: “The views expressed by the WHO don’t have any scientific basis. It’s just a mouthpiece for Western countries,” a Weibo user wrote (in Chinese).

Banned from voicing direct support for Tedros, many Weibo users resorted to sarcasm to circumvent the censorship. “WHO has totally lost its credibility. For Western countries like the U.S., they can’t stamp out the virus because their technology is so behind. China not only has the Sinovac vaccine, it also has the Lianhua Qingwen capsules and Shuanghuanglian. According to experts in Nigeria, the Chinese economy is going pretty well. There’s absolutely no reason for us to move away from the COVID-zero policy,” a Weibo user commented (in Chinese). Another one wrote (in Chinese), “I support China withdrawing from WHO and withdrawing from the Earth.”