This Week in China’s History: May 13, 1127

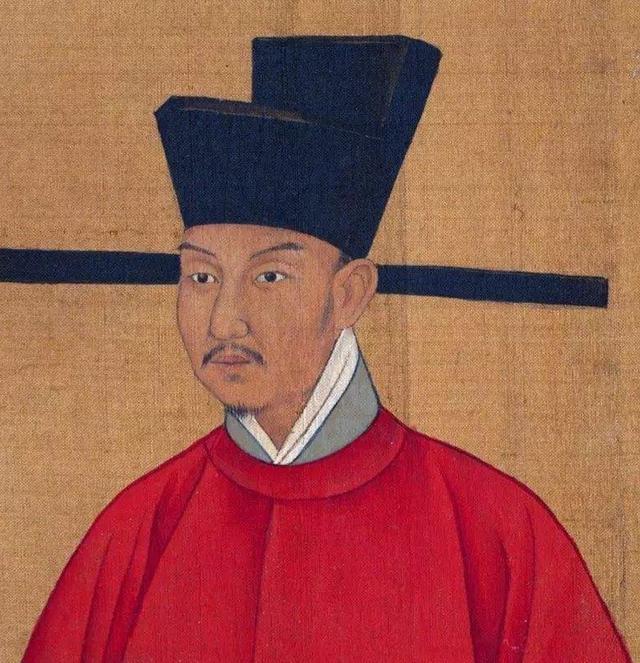

On the morning of May 13, 1127, a man in his late 20s and his father, about 20 years older, passed through the gates of the Song capital of Kaifeng. Two months earlier, the younger man had been emperor of China. Stripped of his title and his status, he was on his way out of his former dominion to live the rest of his life on what today is the northern frontier of China.

The weather suited a momentous change of fortune. A wind strong enough to “move rocks and snap trees,” in historian Dieter Kuhn’s translation of the official Song dynasty history, blew the father and son out of the capital where both had reigned, the elder as Huizong and the younger as Qinzong. Even though an entourage of 3,000 accompanied them, it is hard to imagine that they felt anything but alone.

Huizong ascended the throne in 1100 and had set his sights on expanding back into the territory that his ancestors had lost to the Khitan Liao. To do this, he negotiated with the Jurchens to ally against the Liao, only to see his plans collapse when the Jurchens realized they could accomplish their goals without the help of the Song, and once that was completed, the Jurchens turned their attention to Huizong’s Song dynasty and its capital, Kaifeng.

A century later, Kaifeng would be besieged by Mongols and (probably) bubonic plague, but Huizong had made it a fitting capital for a Chinese dynasty, enhancing its gardens and palaces. But his foreign policy was naive. He had counted on the Jurchens as an ally to help expand his territory, never imagining that they imagined themselves as the preeminent state in the region. A few years after the Liao fell, Huizong was negotiating with the Jurchens to avoid the same fate, offering territory and economic concessions in exchange for peace. Early in 1126, the Jurchens occupied Song territory and laid siege to Kaifeng itself. Desperate to survive, Huizong acknowledged Jurchen control over several prefectures, paid huge indemnities to the invaders, and then, in desolation and shame, abdicated the throne in favor of his son, who would become the Qinzong emperor.

To say Qinzong faced long odds is an understatement. The Jurchens were regrouping for another attack, either to exact tribute, overthrow and occupy the Song regime, or some combination of both. Internally, rebels — supported by dissatisfied ministers — cried treason and worked to supplant the royal family. Only the savviest of rulers had a chance at success in the chaotic and violent world of 12th-century East Asian statecraft…and Qinzong was not that.

Not that he didn’t try. Qinzong purged the court of political opponents — no mean feat given the extent of their influence and high ranks — but the weakened Song was irresistible to the Jurchens. Just months after lifting their siege, the Jurchens again crossed the Yellow River and besieged Kaifeng on December 10, 1126. The capital resisted for a month before Qinzong sued for peace.

This time — even though the emperor agreed to the Jurchen demands — the Song court could simply not comply. When Song officials produced only a small percentage of the ransom demanded, the Jurchens refused the offer and instead killed the officials and took the city. Qinzong abdicated on March 23. The Jurchens claimed an unimaginable bounty: more than 3 million gold ingots and more than 8 million silver ingots, millions of bolts of silk, the imperial art collection, jewelry, ceremonial vessels, and other priceless treasures. Most of this loot was taken north with the majority of the Jurchen soldiers in May.

Like the Ming Chongzhen emperor, who took his own life ahead of conquering armies five centuries later, these men must have contemplated the loss of everything that they had been born to protect. Many members of the Song bureaucracy followed the same path that Chongzhen would, dying by suicide rather than serve a new dynasty. Kuhn presents the example of Dou Jian, who wrote, “I was born to be an official of the Great Song. How could I bear to hand the clan of the Great Song over to enemies?” before ending his life.

Qinzong and his father had to bear the unbearable. Stripped of their noble titles and political power, dressed in the blue cotton robes of servants, Qinzong and Huizong passed out of the gates of Kaifeng on a windy May morning with some 3,000 companions. Soon, a caravan of 15,000 people were making their way north, across northern China to the Jurchen homeland in the northeast.

It took more than three years for the deposed emperors to reach their destination, not far from the site of modern Harbin. Humiliated already, Qinzong and Huizong were given mock-noble titles — ”confused” and ”deeply confused” — and forced to perform mourning rituals to the Jurchen ancestors.

Huizong died in what is now Heilongjiang in 1135, a thousand miles away from his birthplace and a world away from the luxury and privilege of his youth.

Qinzong’s fate was no less tragic, but more complex. His lot improved when the Jurchen-created Jin dynasty normalized their relations with the Song dynasty — his derisive title was amended and he became a minor noble in the Jin aristocracy. But this minor improvement shattered any chance he had to reclaim his inheritance. Gaozong, the Song emperor who had succeeded Qinzong, recognized the Jin’s legitimacy (and in effect became a vassal state of the Jurchens, under the terms of the 1142 Treaty of Shaoxing) and at the same time showed no interest in restoring the former emperor. The dynasty had passed Qinzong by.

In a final humiliation, Qinzong was compelled to compete against another disgraced and defeated former emperor, Tianzuo of Liao, in a polo match. Old and sick, Qinzong fell from the horse quickly. One wonders if he would have preferred the fate of Tianzuo, who attempted to ride his pony to freedom and was killed by Jurchen archers.

Qinzong died at age 61, more than 30 years after being exiled from his kingdom. His story is a reminder not only of the perils of royalty in the 12th century, but also of the turbulence often obscured by the labels of imperial and dynastic succession. The simplified list of dynasties — Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing — suggests that one flowed seamlessly to another. Qinzong, in just a few decades, served one dynasty, was betrayed by another, allied with a third against a fourth, only to be captured and imprisoned for the rest of his life. And within a century of his death, all of those dynasties would be overwhelmed by the Mongol invasions. It could be glorious to be emperor, but glory is often fleeting.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.