A comprehensive mirror: Two years of This Week in China’s History

Marking the second anniversary of "TWICH."

This Week in China’s History debuted two years ago this week. Since that first column…more on that in a moment…I have written more than 100 columns, close to 150,000 words, on topics as familiar as June 4 or the Opium War, and as obscure — some might say trivial — as the first panda to go abroad or the first Tsingtao beer.

To mark the second anniversary of “TWICH,” we thought we would reflect on some of the pieces I have published since June of 2020. Let’s make it a Top 8 — far more auspicious than a Top 10.

1. Remembering to remember, or learning to forget: China’s relationship with Tiananmen 31 years on

Column #1, June 2020

Some events demand attention. Certainly every reader is aware of the significance of June 4, 1989, though there is disagreement on just what its significance is or how it is remembered. The significance of the date made it an obvious choice to begin the column, and I was happy to bring some additional context to the discussion by incorporating Margaret Hillenbrand’s Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China. I feel the most successful of these columns take a familiar event and add some recent scholarship to raise questions about our understanding. In this case, Professor Hillenbrand’s analysis enabled just that: how do people in China remember, or not, one of the formative issues of recent history.

2. The Death of Woman Wang and the Life of Jonathan Spence

#85, January 2022

I had intended for some time to write about the 17th-century murder that provided the title of Jonathan Spence’s 1977 book. Not only did the event give rare insights into the lives of women and the poor during the late imperial era, the book had been one of my first introductions to Chinese history and led me to study with Jonathan. When I heard the news that he had passed away on Christmas Day 2021, I wanted in some way to pay tribute to my former teacher, one of the great historians of China. The approaching anniversary of Woman Wang’s death presented an opportunity to recognize both.

The Death of Woman Wang exemplified Spence’s creativity as a historian. He recovered the past through indirect, often unconventional sources. He brought rural Shandong to life through local histories and fiction, and though little of it spoke directly about Woman Wang, he was able to reconstruct the world she had known so completely that the reader could know her every move and motive. Most controversially, he delved into her thoughts, writing a several-page description of what he imagined her last thoughts and dreams were .

3. Bombard the Headquarters: Echoes of Maoism in the Storming of the Capitol

#33, January 2021

This would be the other most atypical column in the series so far, and the only time that I have scrapped a column to write a new one because of current events. I’ve long been concerned about the rise of ideology in American politics, and in particular the seeming quest for purity among supporters of particular candidates. For the entire Trump presidency, I was constantly reminded of the “better red than expert” principle that guided Mao’s China. Political loyalty, not expertise or credentials, guided government.

When a mob of Trump supporters claimed to be patriots by attacking Congress, threatening our elected leaders and trying to overturn an election, the parallels to Maoism were too strong to pass up. Red MAGA hats took the place of Little Red Books, but the same blind devotion to a leader who believed himself above the government was on display in Washington on January 6 as in the mass rallies on Tiananmen Square in 1966.

4. China’s archives are being erased. Much is at risk of being lost

#25, November 2020

The 18th-century feud between neighbors over a smelly outhouse — that ended in murder — is the kind of random incident that I love to find. The story itself was colorful and fun to write about — and was also the first column to have Alex Santafé’s terrific artwork — but it had its significance not from the event itself but its source. Robert Hegel collected _True Crime in 18th-century China_ by drawing on the rich Chinese archives. Those archives, and not “the toilet murder,” were the real subject of this column. When I was writing Champion’s Day, I could freely access the Shanghai Municipal Archives with only a passport; no letter of introduction or other approval was needed. No longer. Archives and libraries are increasingly restricted, especially (though not only) for foreign researchers. The echoes — or is it the silences? — of these restrictions will linger for years, perhaps decades.

5. In the 7th century, a Chinese coup of Shakespearean proportions

#56, June 2021

Simply put, I loved this story: palace intrigue, treachery, pitched battles. I am always looking for ways to counter my presentist bias — more of my columns are set in the 20th century than all other centuries combined — and the Xuanwu Gate Coup fit the bill.

6. China’s pirate queen Zheng Yi Sao’s final success: retirement

#96, April 2022

The story of Zhèng Yī Sǎo 鄭一嫂, the pirate queen, is sensational to the point of absurdity: prostitution, piracy, incest, and war grab top billing. But maybe the most remarkable achievement of this 18th-century woman was her ability to set up a bureaucratic state that rivaled the Qing dynasty along the southern coast. She commanded tens of thousands of pirates, but as significantly, she successfully challenged the Qing tariff and tax regime in the South China Sea, making it cheaper for the dynasty to give her a pension rather than lose their tariff income. For her part, Zheng Yi Sao may have predicted that increased foreign involvement in coastal trade would make the path she was walking much more difficult.

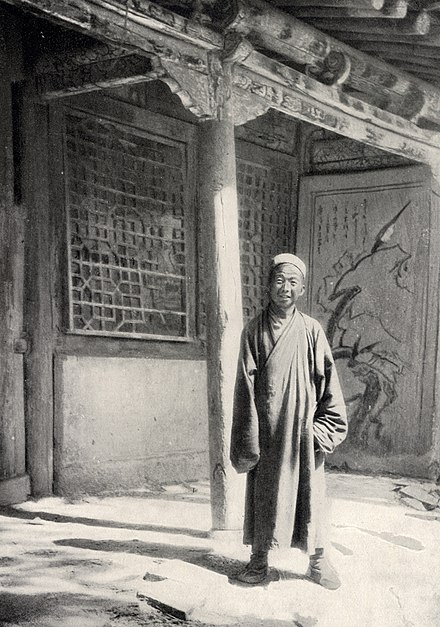

7. Abbot Wang Yuanlu of Dunhuang: Villain or…

#55, June 2021

The question of perspective is at the heart of many historical issues. The fate of the cave frescoes of Dunhuang is a rich opportunity to discuss it, and also a chance to highlight an important recent book, Justin Jacobs’s The Compensations of Plunder. Was Wáng Yuánlù 王圆箓 — the self-described “abbot” of the Mogao caves — a hero for protecting priceless treasures? A traitor to his culture for selling these artworks to foreign “explorers”? A greedy con man? Just someone using whatever means available to make his way in turbulent times? Why choose?

8. There will never be another airport like Hong Kong’s Kai Tak

#57, July 2021

I think this might have been the most fun to write. I used to love planespotting as a kid, and regret that I never visited Hong Kong when Kai Tak was active. If you are an aviation nerd, you have probably already seen videos of white-knuckle approaches available on YouTube — like these — and I heard from dozens of people who remember flying into the old airport.

When I was first approached about writing a column, one of the first things I needed was a title, and while we settled on the very descriptive “This Week in China’s History,” the other contender was “The Comprehensive Mirror.” The title refers back to the Song Dynasty work of history by Sīmǎ Guāng 司馬光, A Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Governance. The title explains how history is meant as a mirror, a reflection that enables us to see what we are and, it is hoped, make changes and improvements. Though we didn’t go with that title — not least of all because it seemed awfully pretentious to compare my words with Sima Guang’s! — it’s still my hope that some of these columns not only entertain, but offer some ways to think about the present in the context of the past.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.