Between Islamophobia and homophobia: Life as an LGBTQ Uyghur in China

Queer Uyghurs are caught between visibility and invisibility, censorship and self-censorship, being "out" and hiding in the closet. It is not safe for them to share their stories. But when they do, they tell of the human desire to belong and to love.

I had a friend who was a medical doctor. He was gay and he was Uyghur, like me. We knew he was HIV positive about a year ago, but he never took any antiviral drugs because he didn’t want his family to find out. Last month, very suddenly he got sick and died just like that — complications from AIDS. His family didn’t even know he was sick, so it was very sudden for them. It’s really sad. There are a lot of young boys, 17 or 18, on Blued. I don’t think any of them understand or know to use protection, and there are a lot of male prostitutes that don’t use protection either.

Erkin told me this story one day when I was living in Xinjiang. The prevalence of HIV among gay men in China was the main reason he wanted to talk to me. “Erkin” is a common male Uyghur name that means “Freedom,” and is a pseudonym. When we spoke, it was 2017 and I was living in Xinjiang. He had heard of me through mutual friends and contacted me on WeChat. He knew I was doing research with LGBTQ Uyghur populations, and he wanted me to know the story of his friend to make sure other people learned about HIV as a public health concern in China.

Erkin was concerned about the spread of HIV due to a culture of silence and ignorance. Experiences of shame around being gay means life and death for many HIV-positive LGBTQ people in China. For Han Chinese, the situation is bad; for Uyghurs, it can be even worse. LGBTQ Uyghurs face disproportionate discrimination due to their status as an ethnic minority battling both Islamophobia and internal group dynamics that vilify homosexuality.

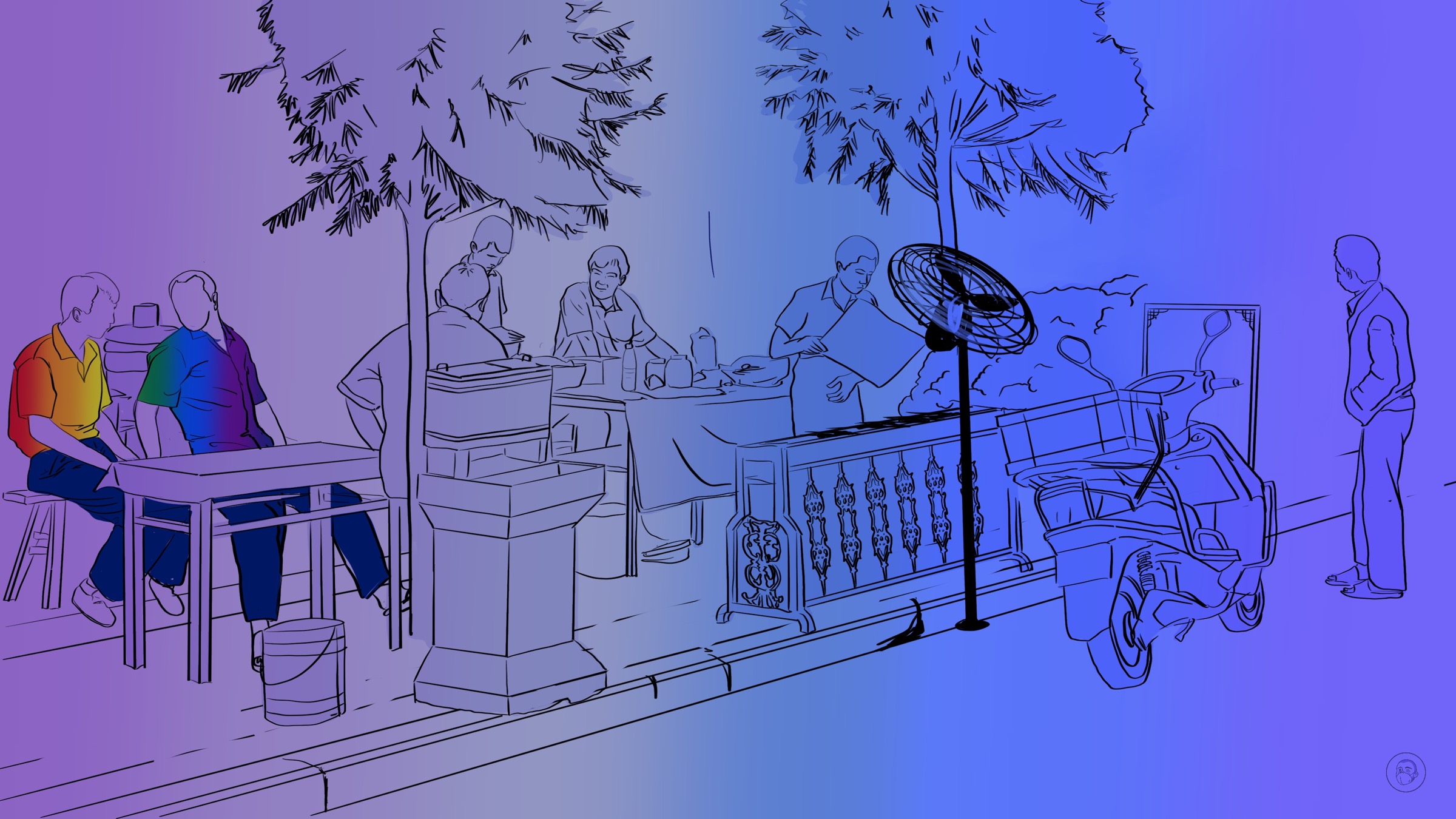

Erkin and I walked around a busy bazaar in southern Ürümchi while we talked. For a time, we sat down at a kabob stand for some grilled lamb meat seasoned with cumin wrapped with naan. The kabob stand included a few tables under a tent; for us it was a tiny haven in the middle of a bustling market. Workers and customers were in close proximity. We had been speaking Uyghur, but at this point he apologized and explained that he would like to speak in English so that others would not be able to understand him. For Erkin, the Uyghur space of the market and kabob stand was not safe. He could only be open if he spoke a foreign language that nobody else there would understand.

Erkin carried himself with confidence and an aura of casualness. He seemed particularly aloof and monotone when relaying his queer life story — his coming out and his romantic history. He was humble and soft-spoken, unassuming and shy. He was mostly unsmiling and serious, but in a kind and gentle manner.

“When I was in high school, I came out to my best friend, who was a girl,” he told me. “She didn’t take it well. She cut off the friendship and we don’t talk anymore. After that I was really scared to come out to my friends, and I kept it a secret throughout college.”

He shrugged his shoulders with his hands in his pockets like it was no big deal that he had been rejected by his best friend and forced back into the closet. For him, such a reaction or attitude was normal and expected. Erkin, like many queer people, especially queer Uyghurs, carried a feeling of isolation when hiding his true sexual identity. While Erkin shared his pain with me, he expressed his desire for the world to know about the struggles of his people, those who were both gay and Uyghur.

After high school, Erkin left China, and it was while abroad that he first began to feel secure in his sexual identity.

“During college, I studied abroad in Europe,” he said. “While I was there, I had a boyfriend. His mom was a really conservative Christian who had a really hard time with her son coming out. But still, he really encouraged me to come out to my mom. He said to me, ‘Mothers always know their children. She probably already knows. You’ll feel so much better.’”

Leaving home, distancing oneself from family pressures, can have a huge influence in broadening one’s understanding of one’s own sexuality. LGBTQ Uyghurs who have been abroad or lived in eastern China have told me that it was after they left Xinjiang that they realized their true sexuality. Their stories emphasized the importance of leaving one’s hometown — allowing for new perspectives and freedom — as a key part of each person’s coming out.

“So, the next time I went home, I came out to [my mother],” Erkin said. “I explained that I wouldn’t be getting married. She cried, but other than that it wasn’t super dramatic. The next day it was as if nothing happened. I didn’t tell anyone else.”

His mother hid her emotions. She was not “dramatic” about it, in Erkin’s words. She did not show anger. She buried her emotions in secrecy instead, not telling anyone else in the family and pretending as though nothing had happened. A sense of privacy and distance between family members (called perdishep in Uyghur, from the root word for “curtain”) was an aspect of Uyghur culture that came up over and over again with Uyghurs, both gay and straight. The secrecy only encouraged Erkin’s masking and pushed him onto the periphery of society. He had to hide from the family that was trying to control him in order to withstand the pressures.

“My younger sister doesn’t know,” Erkin said. “I asked her about gay people to test the waters, and she said, ‘Yes, I have some classmates like that.’ But I could tell she was still closed-minded about it and not ready yet, but I will tell her someday. After I came out to my mother, I started coming out to my Uyghur friends and now a lot of them know.”

Erkin’s story is a story of the human desire to belong and to love. While he speaks to the pain of being queer, he expresses openness as well. He is confident he will come out to his younger sister eventually. Erkin also has a lot of pride and a lot of positive coming-out experiences, along with stories of loving and living.

If one lives in abundance and freedom, hiding may not be as necessary. Erkin had job security and a social network, so he could take the risk of coming out and losing family support. But when one lives in an environment of insecurity, as many Uyghurs do, then such secrets become important for survival.

As other researchers in minority LGBTQ communities have noted, being both a racial or ethnic minority and a sexual minority increases the risk of discrimination with the in-group and out-group, and even within the LGBTQ community itself. No one has done research with the LGBTQ Uyghur community specifically, so there is much we don’t know. But anecdotally, of the Uyghur people I talked to, all of them cited fear of losing their jobs and housing if they came out, not to mention complete lack of family support.

“I have a Han Chinese boyfriend now,” Erikin continued. “I’m not planning on getting a fake marriage with a woman ever, and not really planning on having kids or getting married to him either. I think as long as you’re happy, that’s all that matters. We have a really stable and respectful relationship; we don’t need to get married to prove that.”

Erkin displays a sense of security in his refusal to engage in a fake marriage. A 形婚 xínghūn, which literally means “marriage of appearance,” is a marriage between a gay man and a lesbian woman — a common practice among queers in China. Erkin does not want to live an inauthentic marriage life with a lesbian. In doing so, Erkin pushes back against a culture of shame, secrecy, and hiding, and displays confidence in his relationship, not needing approval from others.

Still, secrecy is a major theme in Erkin’s life. For anyone living in an anxious and insecure situation, secrecy can be a matter of life and death. For Erkin’s friend, secrecy was a death sentence from HIV/AIDS. For other LGBTQ Uyghurs, secrecy is the only way to find distance from suffocating control. They create distance with their family, which ultimately allows them to survive. For others, secrecy is the only way to maintain crucial family ties.

Queer Uyghurs are stuck between Islamophobia and homophobia. As Uyghurs, they experience racism from Han Chinese people and a Chinese government that classifies and targets them as threats strictly on their ethnicity. As queer people, they experience a heteronormative and patriarchal society that pressures them to get married and have children. Uyghur society enforces their oppression with strong gender norms and expectations as well as rejection of same-sex relationships.

In other words, queer Uyghurs themselves are caught between visibility and invisibility, censorship and self-censorship, being “out” and hiding in the closet. It is not safe for them to openly share their stories in Xinjiang. They are hiding with nowhere to go. They are victimized, objectified, erased, and silenced, and further visibility can lead to more violence.

Erikin walked me home at the end of our interview. He told me more of his feelings about how much Ürümchi has changed in the last few years — an explosion of new roads, buildings, migrants, and police officers.

“I used to miss Xinjiang, and when I came home, I would feel like I loved it here and this was my home,” he said. “Now, when I come home, not only because of the politics” — a word he used as an euphemism for the security crackdowns — “but also because I can’t talk about my boyfriend, it feels so strange to me. I don’t even like or want to come home now.”