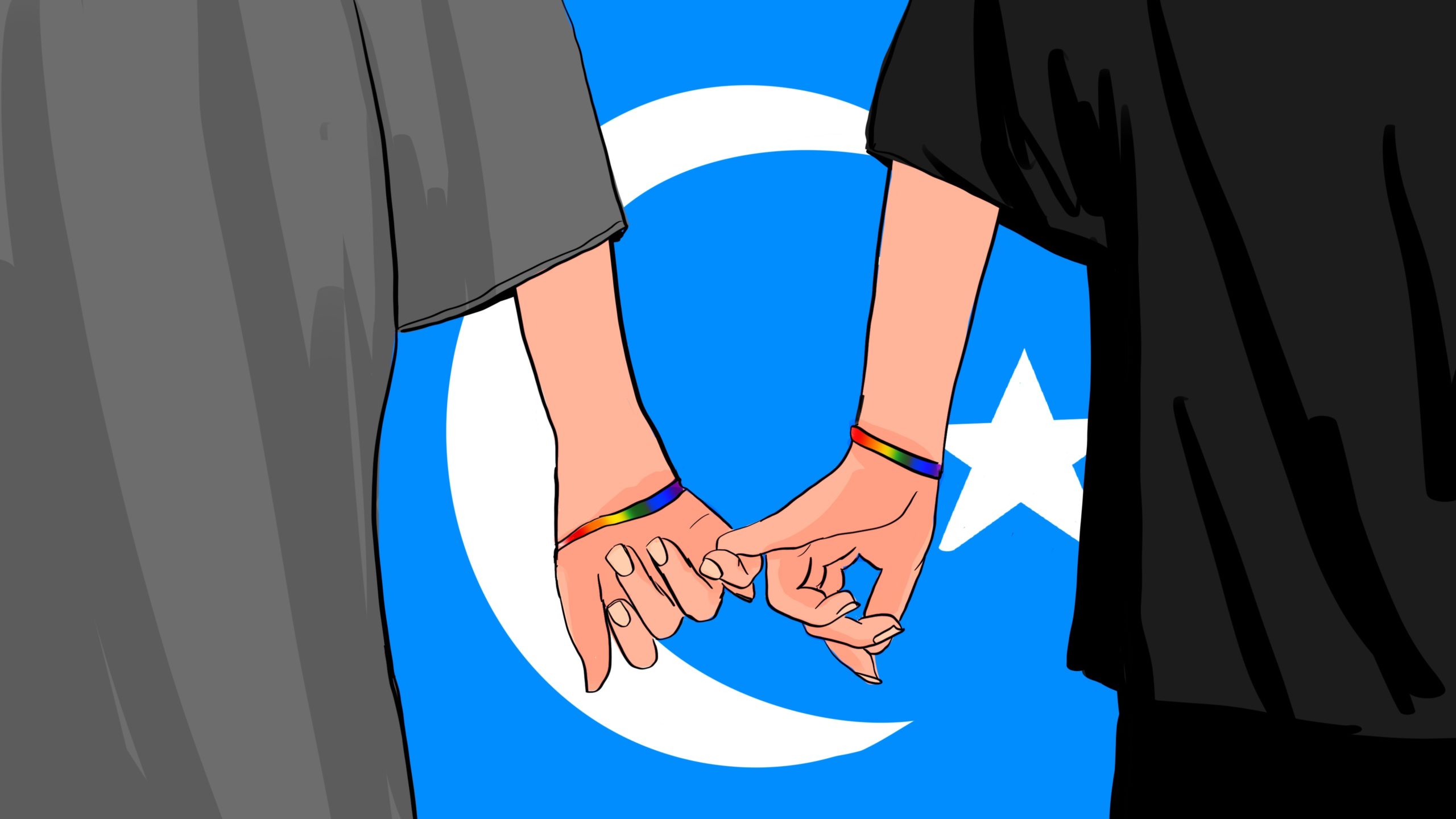

LGBTQ Uyghurs live trapped between layers of trauma

"I like living at home with my parents. To take care of them in their old age would be a great honor, and I could live out my days alone, working in my hometown until my death. If I could choose, that’s the destiny I would pick."

As Pride Month comes to a close, I am thinking about how my queer friends in Xinjiang are doing. When I was doing research there from 2014 to 2017, I was in the closet myself and my original research questions had nothing to do with LGBTQ issues. However, among queer company was the one place I could truly be myself, and I had many close friends in both the Han Chinese and Uyghur LGBTQ communities there.

For many years after returning to the U.S., I didn’t discuss my own queerness or publish about queer topics for two main reasons. First, to protect myself from discrimination, hate, and shame. Second, to protect the identity of those had I met. It is not safe to be publicly out anywhere in the world, but especially in Xinjiang.

After I came out last year as trans, I started writing and presenting about queer issues. I still fear for my research participants’ safety, but I change all names and identifying information in my writing, including in the article below, while keeping the integrity of the stories intact. I only write here what I have permission to share.

My intent in telling these stories now is to raise awareness of these issues so that someday we may live in a world where queer people can share their stories, researchers can investigate queer issues, and queer people can participate in such research — without having to hide details or wait five years for it to feel safe enough.

—Sam Tynen

“There are a lot of messages written in the men’s bathrooms of Ürümchi saying, ‘Add this number for this gay chat group,’ or, ‘Call this number if you’re gay.’ But there isn’t any of that in my rural hometown,” my Uyghur friend Hemrahjan, who is straight, said to me. “We don’t have gay people (hemjislikler) where I’m from.”

It was 2016 and I was living in Ürümchi, learning Uyghur and doing research for my Ph.D. dissertation. I was there to study identity and culture, but found something much more complicated than a uniform way of life. It’s easy to talk about the oppression Uyghurs face, but what I found in the LGBTQ Uyghur community was oppression within oppression: a community that experienced erasure and rejection from both within and without.

“Do you think that might be because of the prejudice that kept gay men there silent or afraid?” I asked Hemrahjan.

“I think homosexuality is a bad influence from the city, or maybe a disorder from Han Chinese culture,” Hemrahjan said. “Why else would those messages on the bathroom stalls be so common in Ürümchi, but nonexistent in [my Uyghur-majority hometown]?”

My friend’s opinion was common among Uyghurs our age. He felt comfortable saying this to me because I was still in the closet, so he didn’t know my personal association with the topic.

“I heard there are a lot of gays and lesbians in Ürümchi, but we have never heard of it in my hometown,” another Uyghur friend said to me on a separate occasion. She didn’t know whether open homosexuality was an outside influence or just a result of economic development, but for her, being gay was not natural and not Uyghur. “Maybe this homosexuality is one of the bad things about development and cultural influence from outsiders and urbanization.”

Hemrahjan and other straight Uyghurs I met associated homosexuality with urban life and Han influence. In the backdrop of a military police state, policing was not limited to the Chinese state, but enforced on bodies by Uyghurs themselves. As the Uyghur community was under threat of cultural erasure, holding on to whatever traditions they could was important. Many grasped and held on to their sense of morality, even if this meant discriminating against the LGBTQ community.

While Hemrahjan declared his disgust over expressions of possible queerness, it was clear to me from his description of the “very common” messages on bathroom stalls that the queer community was nevertheless alive and well in Ürümchi. (I use the word queer interchangeably with “LGBTQ” in this article as an umbrella term to describe sexuality and gender expression that falls outside the mainstream.) I went exploring in Ürümchi.

I eventually found a network of queer Uyghurs online. A number of them reached out individually to meet with me, eager to share their experiences with a researcher with the hope that they might reach the outside world. Patigul was one such Uyghur I met.

Patigul was assigned female at birth and presented masculine, same as me. Patigul was wide and stocky. They sported a short and simple bowl haircut and husky voice. Like me, they wore sneakers and men’s clothes. They never put on make-up. (For Uyghurs, this was a big deal because most Uyghur females adorned make-up daily.) They lived in a small town far from Ürümchi, but came into the city to meet me one day in 2016. (I use they/them pronouns for Patigul even though in Uyghur the third-person pronoun [u] is already gender neutral and the language does not have gendered verbs, pronouns, or nouns. Patigul didn’t speak English, and we never had the opportunity to discuss what their preferred pronouns would be in a gendered Romance language — the concept would have been quite foreign to them — but I use these pronouns out of respect for their gender presentation.)

When they came to meet me at a restaurant one afternoon, they gave the phone to the cab driver so that I could give the driver directions to the restaurant. (This was common practice before smartphones were widespread in taxis; besides, the restaurant we were meeting at didn’t have an address.) On the phone, the Han cab driver referred to Patigul as “xiǎohuǒzi 小伙子,” a slang term meaning “guy” or “dude” and only used for men or boys.

“I get called that all the time,” Patigul explained to me later. “I don’t really fit into either male or female categories. But I don’t mind it when they call me xiaohuozi.”

We sat across from each other at the restaurant holding cups of tea to warm our hands. We were in a Uyghur restaurant and we spoke in Uyghur, so Patigul was worried someone would overhear us talking. Staring at me without blinking, they leaned across the table and maintained strong eye contact, lower lip quivering. We stayed silent for several moments. We just stared at each other, breathing and not knowing what to say. I could see they were about to cry. All I could do was keep eye contact and hold their pain for a moment, but I felt like collapsing under the weight of it.

They continued in a low voice, not mentioning their queerness explicitly but discreetly talking about a subject many Uyghurs in their 20s are concerned about: marriage.

“My parents are freaking out because I’m not married yet, and I don’t think either they or I can stand it anymore,” they sighed. “My parents are so scared I’m going to miss my childbearing years. They’re forcing me to get married. They will arrange it.” Their eyes suddenly grew darker, and they looked down to gaze into their tea. Without looking at me, they continued, “I can’t do it. I have got to get out of here. I have no choice but to leave. I mean, I want to leave China.” They looked up at me again, tears pooling in their eyes. Knowing that Patigul would most likely never be able to leave, I encouraged them to try to find a safe and happy life here.

“Things for us will get better in the future,” I said, trying to comfort them and offer some hope. “Maybe it is our role to sacrifice ourselves. By being out, we can pave the way for future generations to have more freedom than we have. We can be on the frontier of a changing society.”

The sacrifice I was asking them to make was to risk hate by being out but slowly changing society in their own refusal to conform, and being a role model for other gender nonconforming people. I encouraged Patigul to move to the city, get an apartment, and live their life as they wanted and be as open as possible, while maintaining little contact with their parents. This is what many queer Uyghurs in Ürümchi did. Patigul sat staring into the tea, their eyes blinking rapidly and face twitching as their breathing quickened. They shook their head back and forth.

“Your country and this place are so different. Here, we can’t even talk about our situations openly in a restaurant, let alone be open and marry like you can,” they countered back.

I had transplanted romantic foreign ideas to a context still suffering the weight of colonization. I had utopian visions of building a path to change, but my perspective was that of a privileged white person. I had failed to take into account that the freedom to protest and live against the grain — to be “abnormal,” to be queer — is not always feasible, especially for already vulnerable populations. Patigul didn’t have the money to live on their own in the city as I suggested, let alone be out and proud. Besides, they were Uyghur. They were constantly targeted for their ethnicity alone. Patigul was trapped by the limitations of society, family, and nation. I wanted them to be proud and independent; their reality was erasure and double minority oppression.

“I love to eat, that’s why I’m so fat,” they said, trying to inject some light humor into our conversation, chuckling while dipping a piece of naan into their tea as we waited for the Big Plate Chicken (dapanji) to be ready. “You’re pretty, not fat like I am! You should eat more.”

Looking down suddenly, their eyes filled with tears again and their voice wavered. “I like living at home with my parents. I would stay here and take care of them, and just be single my whole life. That I could bear. I could accept it; I could stand it. To take care of them in their old age would be a great honor, and I could live out my days alone, working in my hometown until my death. If I could choose, that’s the destiny I would pick. But my parents will not stop pressuring me to get married. And I fear dishonoring them.

“But I cannot bear to get married to a man, and I cannot bear to stay with my parents any longer under the pressure and their unending disgust for me. Even though I want to stay — I like Xinjiang, I like my hometown, I want to be among my own people — I have no choice but to run away to another country. So that’s my plan.”

A rock sat in my stomach and all I could do was nod and keep sipping my tea. We finished our meal and went our separate ways. Patigul returned to their hometown and we kept in touch, but did not meet again for several months.

In 2017, a year after Patigul and I had the conversation above, the Chinese state confiscated Uyghurs’ passports. Patigul’s shimmer of hope to go abroad dimmed. They messaged me all the time, but I often didn’t know how to help.

Patigul decided to try moving to Ürümchi instead, as I had suggested earlier, and came to the city one day to look for apartments. I hoped that meeting with two Uyghur lesbians I knew, Salamet and Guzelnur, would help Patigul find community. We found an empty bar in a Han Chinese neighborhood one afternoon, ordered tea and spoke in hushed tones in Uyghur — chances were pretty good that those around us wouldn’t be able to understand.

“I can’t live at home,” Patigul insisted.

“I might have to marry a gay man,” Guzelnur explained. “I don’t know. My younger cousins are all married and everyone keeps asking me when I’m going to get married. I just keep saying, ‘I will, I will,’ but the truth is that I don’t know.”

We tried to suggest that Patigul try marrying a gay man, a common practice called xínghūn 形婚 among Uyghur and Chinese LGBTQ people — another form of willing erasure. Patigul shook their head no.

Patigul was trapped. They had no desire to marry a gay man, and who can blame them for not wanting to enter into a lifetime of falsehood and secrecy?

Like Patigul, many queer Uyghurs found themselves ostracized by their own families as well as discriminated against by society at large. If Patigul got an arranged marriage to a man, they would have had to live with that bodily and emotional trauma for the rest of their life. Losing sovereignty over one’s body in this way is part of the reproduction of state and colonial violence, which overlapped with trauma in the family. State and colonial violence are often reproduced in the family and on the body for the most vulnerable populations.

We parted ways with promises for all of us to hang out again. Little did I know, that would be the last time I saw them. It soon became too risky to meet with a foreigner or have a foreigner on WeChat.

The situation for Uyghurs only got worse as 2017 continued, when people continued to disappear into internment camps. I ended up losing touch with many others in the LGBTQ Uyghur community, who were struggling to find housing and getting separated from their partners.

I don’t know how their stories will end, but I hope to spread the awareness that they exist and that their identity is valid and inherent, not an implant from foreign cultures.