Sanxingdui — an archaeological site in Sichuan province brimming with artifacts dating back 5,000 years — challenges China's dominant founding myth and the idea that the Chinese people arose from a single point of origin.

The discovery

The year is 1986. The location: Guanghan City, a sleepy sinew of farmland situated in the heart of the Sichuan Basin, China’s breadbasket. Nestled between rippling fields of rapeseed flowers sits a rudimentary open-air building, the Lanxing Second Brick Factory. In the sweltering July heat, laborers from the factory excavate the ground nearby for clay from which to process into bricks. As their shovels paw at the soft, cloven earth, one of the workers strikes something hard. Upon closer inspection, he discovers that it is no ordinary rock that he has come across…

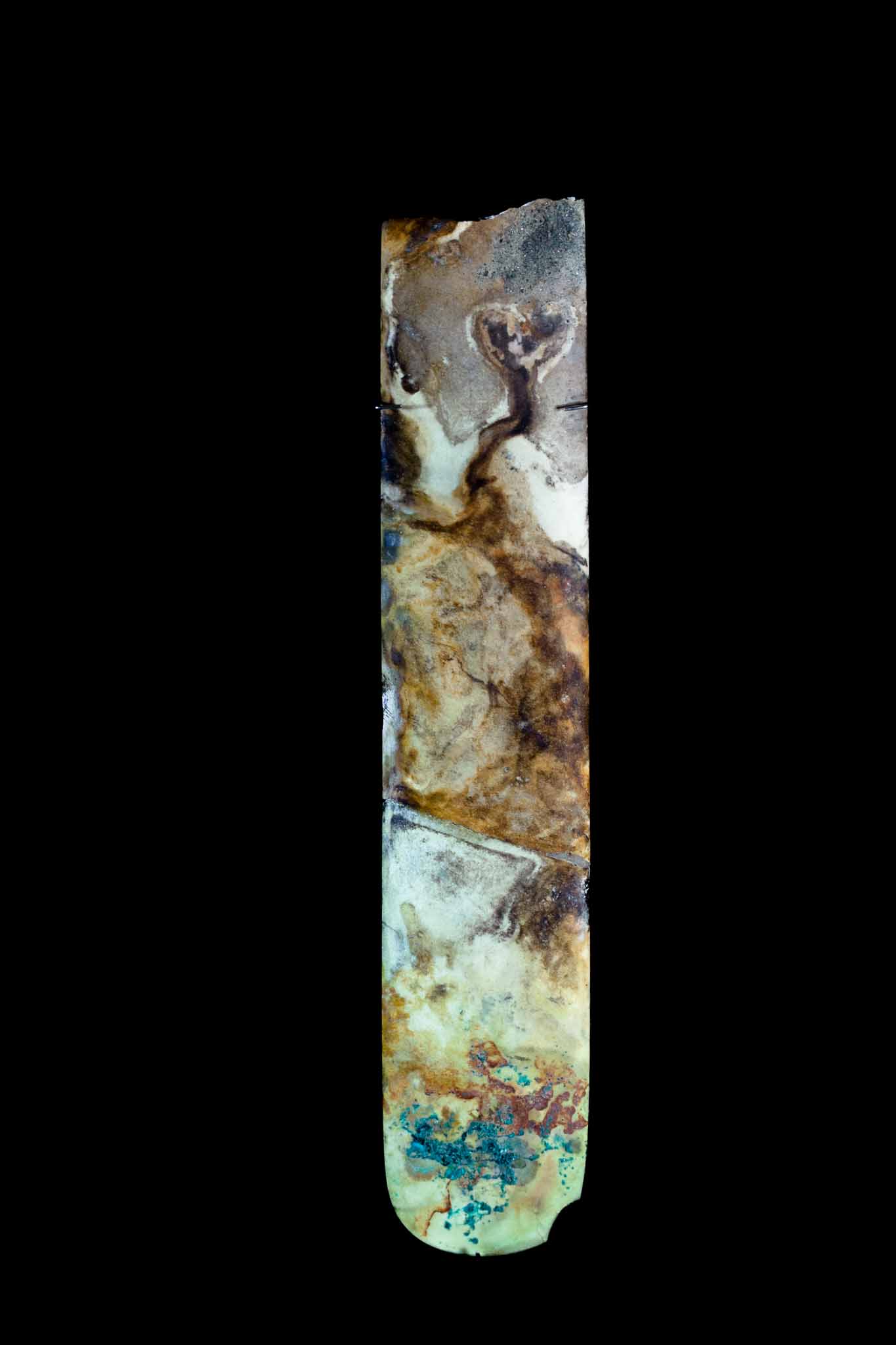

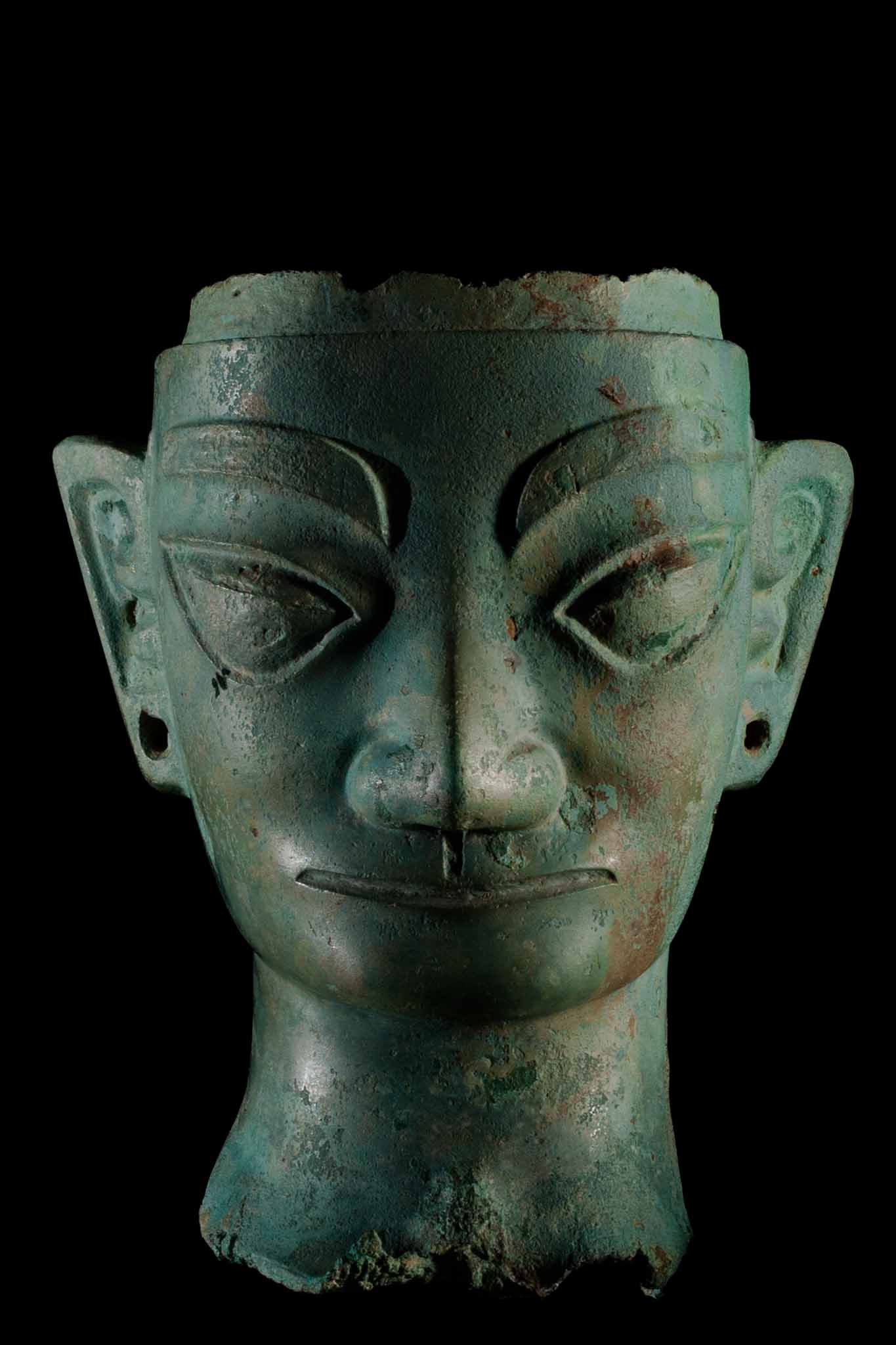

By sundown, a cache of jade dagger-axes and tablets, more than 10 in all, lay spread out on the earth, their surfaces having not seen the light of day in over 3,000 years. The authorities are notified, and by week’s end archaeologists from the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archeology Research Institute descend upon Guanghan County to begin a months-long excavation effort. Their subsequent discovery would be one of the most significant archaeological finds in China: two large sacrificial pits brimming with weapons, elephant tusks, oversized ceremonial bronzes shaped in the form of human heads, and mysterious masks leafed in gold.

Over the next three decades, even more sacrificial pits are found, with the most recent discovery happening as recently as this month. Each of the pits is full of exquisitely preserved artifacts dating back nearly 5,000 years. These artifacts have come to be known as the treasures of Sānxīngduī 三星堆. Pointing to a mysterious Bronze Age civilization, it has upended the 2,000-year origin story of how the Chinese people came to be.

The first time I laid eyes on the Sanxingdui artifacts, I was struck by their bizarre appearance: the oversized bronze heads featured almost comically bulging eyes, elfin ears, and impenetrable smiles. Of the many origin hypotheses floating on the internet, the more outlandish ones suggest the relics belonged to a long-lost alien civilization; indeed, alien conspiracies are nothing new to the field of archaeology, but the treasures of Sanxingdui are so unlike anything found before, their designs so idiosyncratic, that it’s not difficult to see why people would assume aliens over ancestors. As I gazed at these strange relics from another time, a question crossed my mind: what makes something, or someone, Chinese? What are the parameters? And are they fixed…or flexible?

In many ways, I was drawn to the story of Sanxingdui because of my own background. I was born in China but left with my parents at the age of two to immigrate to the United States. Like many children of immigrants, exposure to the country of my heritage was limited by geographical distance, yet I credit my parents for keeping the culture alive at home. Growing up, a normal weekend consisted of neighborhood baseball preceded by home-schooling of Yǔwén Kèběn (语文课本), elementary school language and grammar books my father brought back from China. This type of upbringing had a profound effect on me: I felt natural acknowledging and embracing both American and Chinese aspects inside of me. Society, uninterested in nuance, tends to make us choose one side over the other, but why choose when there was room for both?

After university, I made the decision to move to China, and a world that had for so long been relegated to the realm of conjecture sprang forth into reality with commanding urgency. For the next decade, I discovered China with my camera, shooting documentaries and photo stories that would eventually lead to a career as a filmmaker and National Geographic photographer. Through these experiences, I came to see that rather than proverbially slicing my identity into narrower and narrower definitions, I was better off embracing both the American and Chinese aspects I carried within. I saw that the treasures of Sanxingdui mirrored what it often felt like to be Chinese American: a paradigm outside of the conventionally accepted narrative of what constitutes being Chinese, yet whose presence invites us all to reconsider our definitions.

The power of myth

Sanxingdui challenges the dominant narrative that the Chinese people arose from a single point of origin: the Yellow River Valley, which for two millennia was proclaimed the cradle of Chinese civilization.

Civilizations all over the world have their founding myths: Romulus and Remus, Moses and the burning bush, Arthur and the sword. But what purpose do these myths serve? From an academic perspective, founding myths explain a society’s existence and the order of the world. This order is often established with the assistance of sacred or higher forces as a way to reinforce its authority. In simpler terms, founding myths are stories describing where we came from and how we came to be…in order to make sense of who we are.

China’s traditional founding mythology centers around the Yellow River Valley: the Chinese version of the Fertile Crescent. Chronicles of god-like sage-kings who conducted mighty works such as introducing fire, teaching agriculture, and taming the flooding of the Yellow River became part of the foundational myth explaining the formation of the legendary dynasties of the Xià 夏, Shāng 商, and Zhōu 周: three ancient cornerstones of Chinese heritage and identity.

Throughout the last 2,000 years, this mythology has been told and subsequently refined every generation. From the Shǐjì 史记, the Records of the Grand Historian, written in 94 B.C.E., to the 16th-century Ming dynasty epic Investiture of the Gods (封神演义 fēng shén yǎnyì), to popular media today such as blockbuster animated films like Ne Zha (哪吒 nǎ zhā) and Legend of Deification (姜子牙 jiāng zǐ yá), Yellow River Valley mythology is as inseparable from Chinese identity as Arthurian legend is to British identity, and as foundational to Chinese thought and storytelling as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey is to the West. It is not an overstatement to assert that Yellow River Valley mythology is Chinese identity. It is even baked into the language: the ancient origin of the Chinese word for China, Zhōngguó 中国 — the Middle Kingdom — coined in the Zhou Dynasty, refers to the central states that called the Yellow River Valley home, in relation to the “barbarian” tribes that occupied its periphery.

The ancient kingdom of Shu

In comparison to the Xia, Shang, and Zhou, we know very little about the Bronze Age societies that existed outside of the Yellow River Valley. Scant evidence of their existence, either written or physical, exists. Yet how can we be so sure they weren’t just as advanced?

This is where the discoveries at Sanxingdui come in, blowing a hole in the traditional narrative.

Covering an area of nearly four-square-kilometers, the ruins of Sanxingdui are replete with ancient walls made of rammed earth, building complexes, and even water conservation facilities. A ruin this large and organized indicates a clear distinction between countryside and city, making a compelling case for a civilization rather than a patchwork of tribes.

Currently, scholars have not reached a conclusion as to who the Sanxingdui Civilization was, yet many believe them to be the Shǔ 蜀, a kingdom first mentioned in the Book of Documents (书经 shū jīng). In it, the Shu was described as a tribe coming to the aid of the Zhou during the overthrow of the Shang Dynasty. Considered by many to be an unsophisticated barbarian society, the Shu were quite literally written off by ancient historians. After all, their home in the Sichuan Basin was surrounded by imposing mountains on all sides, and was historically considered a cultural and political backwater, geographically isolated and of little importance to the central states vying for power in the Yellow River Valley. Now, the discoveries at Sanxingdui have reopened dialogue on the Shu Kingdom as the force behind the Sanxingdui civilization.

The future of ancient history

There’s an old saying: if you don’t write your own story, others will write it for you. As China’s president Xí Jìnpíng习近平 marches toward an unprecedented third term in November, his methods of steering the country toward “national rejuvenation” as well as asserting China’s power on the global stage are becoming increasingly forceful. In recent remarks, Xi stressed the importance of furthering the study of Chinese civilization, to “enhance the historical awareness and cultural confidence of the Communist Party of China and society.” Adding that Chinese history “is also the foundation of contemporary Chinese culture,” Xi deemed it “a spiritual bond that binds Chinese people around the world, and the treasure of Chinese cultural innovation.” Spoken at a Central Committee group study session, these comments are meant to provide guidance for a national research program dedicated to tracing the origins of Chinese civilization. But read between the lines, and they testify to Xi’s keen awareness of the power of a national mythology.

This brings us back to the strange faces of Sanxingdui. How they will fit in Xi’s narrative, no one knows. For two millennia, the Yellow River Civilization mythos has had the benefit of unchallenged dominance, and yet these bronze faces remind us that there is more to this story.

As modern Chinese archaeology enters its second century of existence, the discoveries at Sanxingdui have opened the gates of possibility, allowing for a multipolar origin story more fascinating and complex than anyone has ever imagined. Yet under Xi’s China, a founding mythology — even history itself — is a narrative that is to be actively shaped to serve the needs of the state. Though it remains to be seen how Sanxingdui is incorporated into the CCP canon of Chinese history, it should not be seen as a challenge to the narrative of the Yellow River Civilization; rather, it is a humbling reminder that our definition of what it means to be Chinese must be broadened beyond its current scope.

What makes someone Chinese?

Some will say it’s ethnicity and language. Others, a shared history. Still for others, the determining factors may be philosophy, religion, aesthetics. Yet not one aspect stands alone; they are part of a whole. Zooming out reveals the larger context of a civilization perpetually in search of itself. As archaeologists continue to unravel the mysteries of Sanxingdui, each new discovery offers new insight in just how diverse Chinese civilization really is. The enigmatic faces of Sanxingdui seem to agree. With mouths curving upward into sly grins and eyes seemingly staring far off at a sight beyond our time and space, they cannot answer us with words.

Yet they challenge us to look past the threads of the present, toward the larger tapestry of history. By their mere existence, they remind us there is a place for those who do not fit neatly inside the narrow definitions set by the states and principalities of the Middle Kingdom. They are every bit as Chinese as those within it.