The not-so-scary truth behind horror sensation ‘Incantation’

Audiences are raving about Taiwan’s newest horror film "Incantation," which just hit international Netflix this month. Exactly how real are the religious elements at the center of the movie?

This month, the Taiwanese film Incantation (咒 zhòu) hit international Netflix: a found-footage horror movie following the experiences of a cursed woman — and the consequences of the curse. Viewers were quick to hype up the film, daring others online to try and sit through the whole thing.

Since its premiere in March, the movie has become the highest grossing Taiwanese horror film of all time, and Taiwan’s highest grossing film of 2022. Incantation also finds itself at the center of a debate on the Chinese social media platform Weibo. The hashtag “Is Incantation scary?” (咒吓人吗 zhòu xiàrén ma) has garnered millions of views. The ultimate consensus: not that scary, but still worth watching.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

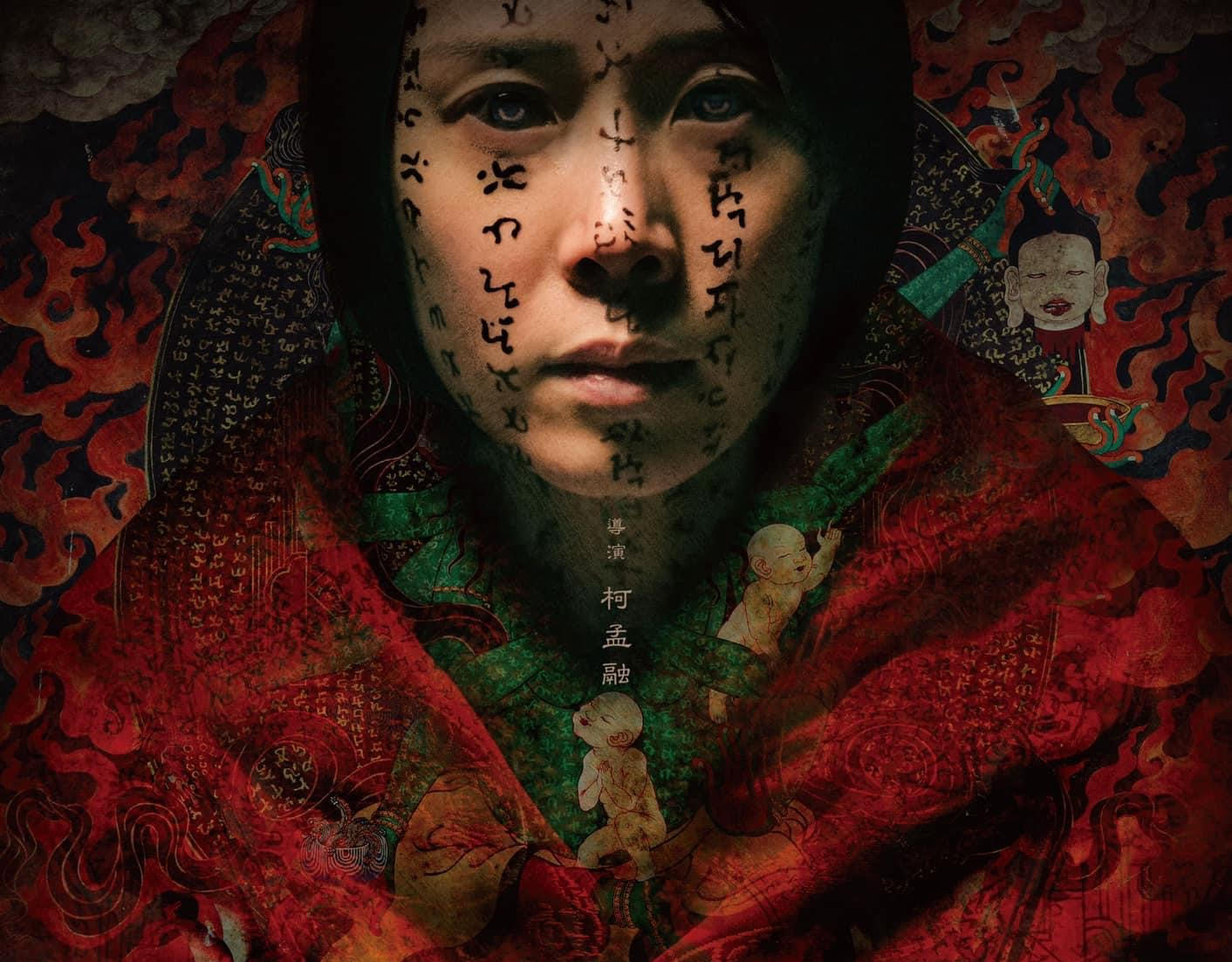

Something feels different with Incantation. Directed by Kevin Ko, the movie interacts with its viewers. The protagonist, Ronan (Tsai Hsuan-yen [蔡亘晏 Cài Gènyàn]), leads the audience through mind exercises, directing chants to be spoken. By the end of the movie, you feel like you’ve been tricked. Maybe cursed.

The movie is set around Ronan’s curse after she breaks a religious taboo while ghost-hunting in Yunnan province. Ronan and her two friends visit a remote village practicing an extreme form of Buddhism. They become wrapped up in a local ritual, unknowingly binding themselves to Dahei Mother Buddha.

During their ghost-hunt in forbidden parts of the village, Ronan’s two companions face disturbing deaths. She leaves the village and returns home, haunted by a supernatural curse. Ronan falls in and out of raising her six-year-old daughter Dodo (Huang Sin-ting), who faces similar strange occurrences.

Incantation opens with “Based on a True Story,” and most have guessed its inspiration comes from an ominous incident that took place in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. In 2005, a family there claimed to be possessed by demons, performing disturbing ritual acts and killing their two daughters. But what the movie really wants you to think is that it’s the curse at the film’s center that is real. Citing a modified form of Tantric Buddhism and Brahmic script, the movie explains how the religion traveled from Southeast Asia to Yunnan province. The story also conjures up its own symbols and rituals. But how “true” is it, really?

Let’s take a closer look.

Dahei Mother Buddha

The curse and religion in Incantation revolve around the worship of Dàhēi Fúmǔ 大黑佛母. This is a fictitious deity that isn’t present in any religious mythology. Instead, its inspiration likely comes from Tantric Buddhist figures Dàhēitiān 大黑天 and Dàhēinǚ 大黑女. Specifically, Daheitian was sent to share blessings among poor people. This ties back to a part of the film’s curse backstory: that misfortune and blessing are intertwined.

In ancient Brahmanism, a version of Dahei exists as “Kali.” There was a real-life case where a cult worshipper of Kali subjected herself to blood sacrifice. In 2016, a woman cut off her tongue in worship of Kali in the hope that the goddess would fulfill her wishes. We see similar sacrifices in Incantation, where a young girl cuts off her ear to appease Dahei.

In India, Māyā, the Mother of Gautama Buddha, laid the foundations for the teachings of Buddhism. In Chinese, she is known as Móyé Fūrén 摩耶夫人. Tradition says she died soon after giving birth to Buddha, returning to life after seven days. This draws an eerie parallel to a subplot in the movie: Ronan visits a temple to seek help for her dying daughter Dodo, where a priest orders Dodo to not eat for seven days. Only after that can they lift the curse.

In the film, statues of Dahei have her face covered with a cloth. It’s implied that Dahei’s real power rests in her face — and if anyone removes the cloth and looks, they are destined for a gruesome death. Ronan’s two friends unveil the face of Mother Buddha in a forbidden tunnel, and frightening chaos ensues. That is one of many taboos they break. It isn’t until the end of the film that we the audience see the deity’s face. (My deepest condolences for any viewers with trypophobia.)

There is no Tantric Buddhist practice of covering a deity’s face. In fact, traditionally Buddhist statues should face a door or window for clarity. In the film, Dahei is turned away from onlookers. There is a clear disconnect from fact here, but the artistic choice to position and dress the Mother Buddha statues adds to the movie’s creepiness.

The incantation

Throughout the movie, Ronan begs the audience to chant “Hou ho xiu yi, si sei wu ma” (as rendered in the English subtitles; in Chinese, it is 火佛修一,心薩嘸哞). She tells us that reciting this incantation will stop the curse from escalating in the moment. Ming (Kao Ying-hsuan [高英轩 Gāo Yīngxuān]), Dodo’s caretaker from her brief stint in foster care, does some online digging to find the origins. His findings eventually lead him to a secluded monk practicing Tantric Buddhism in Yunnan — one of few who can translate the incantation. He is told the incantation comes from a Minnan dialect, meaning: “Misfortune and blessing depend on one another, death and life lies in the name.” There is a twist, which I will not reveal for fear of spoiling it.

The Minnan language originated in Fujian province. Min Chinese spans across a broad range of Sinitic dialects, which are spoken mainly in Fujian and much of Taiwan. Min Chinese is practiced along the coastal regions of eastern China, spanning from lower Zhejiang down to the island province of Hainan. Yunnan lies southwest of the language’s influence. So it’s not impossible that Minnan could have made its way there, especially if the monk is from the Minnan region.

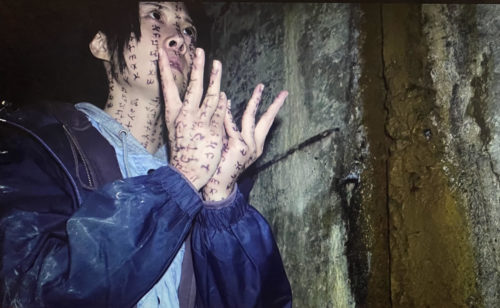

The “Hou ho xiu yi, si sei wu ma” mantra bears no relation to any of Tantric Buddhism’s spiritual practices. Tantra religions do share a commonality: sacraments or rituals are used to conjure divine energies. We can see vestiges of this idea in Incantation: a sacramental young girl is covered in writing, used in ritualistic practices to appease Mother Buddha. This extreme practice is not found in Tantric Buddhism.

The hand gesture

A specific hand gesture accompanies the chant — which later in the movie is found to be rooted in a modified version of “bāfāng tiān” 八方天 in Tantric Buddhism. Ming even unearths how-to YouTube videos of the hand motion — except the people in the esoteric village sign it backwards.

After some digging, I found no similar Buddhist hand gestures performed forwards or backwards.

The symbol

Then comes the infamous symbol that Ronan directs audiences to memorize. The symbol itself doesn’t correlate with any modern Chinese characters. At most it mimics some features of simple incantation images — but not enough to warrant a sensible comparison. But it is mesmerizing, and its details add to the terrifyingly realistic world of this made-up religion.

The esoteric religious community in Incantation is fictitious — though some parts feel real. The film takes components of Tantric Buddhism and Brahmic script and spins them into a new reality. It is true that Tantric Buddhism took hold in China in the 700s, during the Tang Dynasty. Tantra masters traveled from India to China, bringing their esoteric teachings. Tantric Buddhism subsequently grew in popularity, influencing other forms of Buddhism that reached China. However, Tantric Buddhism is rooted in the peaceful use of the mandala (geometric symbols), mantra (religious phrases), and mudra (ritual gesture). Incantation takes these principles and runs in a very different direction. Is it a scary direction? That we’ll let you decide.