‘I wasn’t the only person being otherized’: In conversation with Bruce Humes

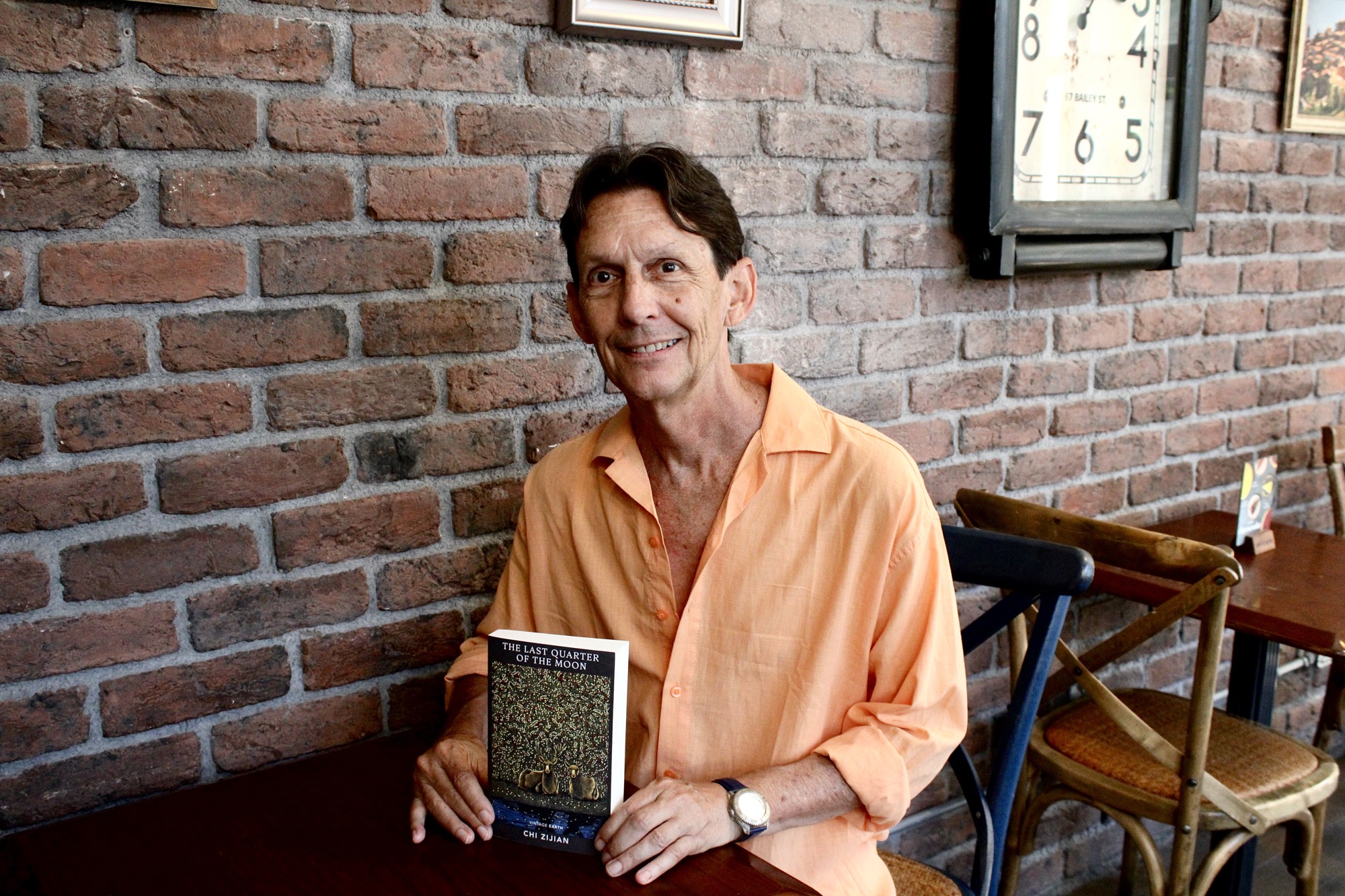

American Bruce Humes has been translating Chinese for more than two decades, specializing in literature by non-mainstream authors. One of his defining works — a translation of Chi Zijian’s award-winning "The Last Quarter of the Moon" — has just received a re-release from Penguin Random House.

Polyglot Bruce Humes worked in China for more than three decades as an export management trainer, launching B2B magazines for Chinese managers and translating fiction. He left the mainland in 2015 and has since lived in Taiwan, Malaysia, Tanzania, and Turkey, but continues to write about the Sinophere.

Humes is a renowned translator of Chinese. He says he was drawn to the language after encountering two very disparate works: Mao Zedong’s early essays, particularly his 1927 Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, and The Book of Tao. “The former because, youthful and idealistic, I was tantalized by the thought of a socialist revolution in action, and the latter because I was shocked to find that translations of Taoist philosophy could be so utterly and almost ludicrously different,” Humes told us. “This made me want to master classical Chinese and get to the bottom of this mystery.”

Among novels, Humes is perhaps most well known for his translations of Wèi Huì’s 卫慧 Shanghai Baby (2001) and Chí Zǐjiàn’s 迟子建 award-winning The Last Quarter of the Moon (2005), the latter of which was relaunched last month by Penguin Random House, 10 years after its original publication in English. Rebranded as “eco-fiction,” this parabolic tale looks at the fate of the Evenki clan of Northeast China’s Heilongjiang province.

Humes recently spoke to us from Turkey, where he currently resides, about his work and how he views China from afar.

In 2015, you decided to leave China. Why, and where have you been living since?

In 2013, I left China, temporarily in my mind, for Turkey, where I intended to take a break and study Turkish. Little did I suspect that I would encounter the historic Gezi Protests when the young poured onto the streets, initially to protest against turning Istanbul’s Gezi Park into a shopping mall, but eventually into boldly dissing the rule of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then prime minister, now all-powerful president. It was a fantastic time, recalling the flower-child protests of the 1960s in the U.S. But when I returned to China, perhaps due to my experience in dynamic Turkey, I felt newly uncomfortable with the lack of critical thinking; in short, it was time for me to exit a country I had long called home. I’ve commuted between Taiwan and Malaysia for several years, and am currently back in Turkey attempting to master Turkish.

You’ve been busy translating books since leaving China, as well as essays and excerpts. Why have you chosen the life of a freelance translator?

Well, certainly not for the money! I’ve gradually realized that managing business publication content and people for a corporation meant that I didn’t have the energy to do what I really felt like doing: Writing about things that are important to me. To a large extent, the topics that I want to explore relate to insights and phenomena that I’ve encountered thanks to 30 years in the Sinosphere, and that can include translating. For instance, I recently enjoyed translating My Heart Belongs to Dunhuang (我心归处是敦煌 wǒ xīn guī chù shì dūnhuáng) by the dedicated female archaeologist Fán Jǐnshī 樊锦诗, who spent 50-plus years in the desert preserving and documenting the Buddhist cave-temples at Mogao.

In 2009, you started blogging about Chinese ethnic-minority literature. Your website has since evolved to cover a broad array of topics including African literature and literature of Altaic peoples. Why has your intellectual interest taken you to these parts of the world?

It’s been a relatively natural evolution, actually. As a foreigner in Chinese society, I gradually realized that I wasn’t the only person being “otherized.” I launched my blog, Ethnic ChinaLit: Writing by & about non-Han Peoples, to explore how peoples like the Zhuang, Evenki, and Tibetans perceived the mainstream Han, and vice versa, and how this found reflection in contemporary novels. Along the way, I decided to try my hand at one of the non-Sinitic languages spoken on the fringes of the Chinese empire. Perhaps because I have spiritually always felt myself a northerner, I was attracted to the Altaic languages, which comprise Tungusic (e.g., Manchu, Evenki), Mongolic, and Turkic tongues (spoken from Xinjiang through the Stans to Turkey).

The reason that I was motivated to compile my bilingual mini-database of African Literature in Translation was that China was snapping up so much of the continent’s mineral goods, I wondered when “cultural imports” would follow. So I decided to try to quantify it, and the list now comprises 270 works by over 100-plus African authors.

You translated Chi Zijian’s The Last Quarter of the Moon in 2012. It has now been rebranded and newly launched as part of the Vintage Earth series. How do you feel about it 10 years on?

I feel the book is more relevant than ever. On the one hand, it highlights the challenges that face isolated indigenous peoples, such as those in the Amazon jungle right now, in dealing with “intruders.” But it also raises important questions for “modern” societies: Did the Evenki leave the secluded mountains to offer a better material life to their children? Are they “eco-migrants” — China’s preferred official designation — who relocated due to the unfortunate erosion of their traditional habitat? Or are they eco-refugees, forced to move to “civilized fixed settlements,” in order to facilitate massive logging of their environment? In essence, habitat destruction, eco-migration, and the struggle of pre-industrial peoples to adapt to the 21st century are all timely topics. This repositions Last Quarter as a shining example of the highly topical eco-fiction genre, and distances it from the “ethnic China” box.

You’ve remarked that this is the translation you’re most proud of. Why?

My very first translation, Shanghai Baby (2001) — initially a best-seller in English and available in more than a dozen languages — won me a (dubious) moniker as a translator of “soft porn.” Even today, clients contact me thanks to that work! I thoroughly enjoyed bringing Nikki’s naughty affair with her sexual Übermensch to the English-speaking world; titillating, perhaps, but it’s hardly great literature. Last Quarter, on the other hand, is a moving, first-person narrative that places us very believably in the mind of an Evenki woman who has survived the ravages incurred by the Japanese and Han over the course of the 20th century.

You lived in what many now view as a uniquely liberal time during the roaring 1990s and 2000s. How do you view China’s slip back into a more authoritarian mode?

Today’s surveillance society is mind-blowing for me because I spent much of my time in what was arguably the wildest part of China, the border town of Shenzhen. As long as anyone, Chinese or foreign, kept their nose out of politics, you could do just about anything you liked. To my mind, this Wild West ambiance began to transmogrify in the run-up to Beijing’s Olympics in 2008, and the emphasis on “stability maintenance” under Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛. By the time I exited in 2015, a foreigner could no longer live without reporting their address to the authorities, something that I had rarely bothered to do. I assume that Shenzhen is now a very effectively monitored city, but although cameras were installed almost everywhere by the time I left, most residents still felt free to live an anything-goes lifestyle. This is surely not the case today, as COVID has given the authorities the plausible excuse to perfect 24/7 surveillance.

The Sinosphere is seldom out of the news these days. As you occasionally blog on what’s happening in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, what is your view on the growing tensions in these regions?

With regards to Xinjiang, there is an overwhelming amount of propaganda and confusing commentary out there, disseminated by China media and anti-China, anti-Communist players as well. But in my opinion, there is ample evidence that since 2017, Xinjiang’s Turkophone peoples have been the target of a very intense campaign of incarceration and surveillance that aims to assimilate them and reshape them into secular citizens who speak the national language and behave like mainstream Chinese. Perhaps most ominous is the practice of placing Uyghur children in live-in schools or, if their parents have been disappeared, in orphanages. The entire curriculum is in Chinese, and mother-tongue speech is forbidden. This recalls the “residential school system” established in Australia, Canada, and the United States for many decades during the 19th and 20th centuries. This schooling solely in English proved alienating and deeply traumatic for several generations of indigenous peoples, and it is very alarming to see it being systematically embedded in Xinjiang.

It’s actually a bit tricky to talk about Hong Kong because it never functioned as a democracy, but it had some precious trappings: relative freedom of speech, the press, and public protest, which were specifically to be protected under the Basic Law. The National Security Law makes a mockery of these “rights.” I feel very downhearted about what has happened to Hong Kong society as a whole since the unilateral promulgation of the law — no Hongkongers were involved in its drafting — and its swift and brutal implementation. I married and raised a family there in the 1980s, and deeply appreciated the efficient civil service and overall ambiance of the city. Hongkongers are much nicer and less obsessed with money than popularly believed. Seeing the police weaponized by the administration has shocked me.

I think what has effectively become Beijing’s direct rule over Hong Kong is a good lesson for Taiwan residents, particularly the young: If you thought the PRC had become a remote presence, more or less irrelevant to you and your future, think again.

Outside of learning Turkish and translations to pay the bills, what do you hope to achieve in the future?

I’d like to travel through the Stans, perhaps in 2023. It would be interesting, of course, to see how Turkic dialects differ between, say, Turkey and Uzbekistan, but more importantly I’d like to seek out the increasingly rare performances of various forms of ancient Turkic storytelling: epics such as Dede Korkut, Manas, and Koroghlu; hikaye (folk romances); and dastan (tales of heroic deeds). And if I find the time, and a friendly publisher to support it, I would also like to translate Guo Xuebo’s Mongolia (蒙古里亚 Ménggǔ lǐ yǎ), a novel I like very much because it is subtly subversive.