Song Jiaoren and broken promises of the Chinese republic

Song Jiaoren is China's "lost future," remembered as a democrat who opposed authoritarianism — and not for reneging on promises in the naive hope that he could build an electoral coalition.

This Week in China’s History: August 25, 1912

More than one thousand people were gathered on a Sunday morning in Beijing for the first convention of the Kuomintang (KMT, 国民党 guómíndǎng), or Nationalist Party. Reorganized from Sun Yat-sen’s (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) Revolutionary Alliance, the KMT was going to be the driving force in the parliamentary politics of the new republic. Sun, its ceremonial leader, had just resigned as provisional president, enabling Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凱 to take the role. Sun was at the presidential palace to negotiate with Yuan over the nature of the new government, which brought into relief the uncertainty facing the new republic.

A revolution had overthrown a 250 year-old-dynasty, and now a new government was taking shape, but what shape would it take? The delegates and spectators packing the Huguang Guild Hall (湖广会馆 húguǎng huìguǎn) — the lodge for natives of Hubei and Hunan provinces — were there to determine nothing less than China’s future.

Historians have a tendency to lionize, or demonize, the dead. In polarized times like these, the tendency is even greater: historical figures were heroes or villains, geniuses or fools. We spend a lot of time tearing down supposed role models or rehabilitating failures.

In this vein, let’s consider Sòng Jiàorén 宋教仁. He is, famously, China’s “lost future.” I wrote as much earlier this year, comparing his death to “the assassination of Chinese democracy.” I am not the only one to have posed the counterfactual, What if Song Jiaoren had lived? In light of the decades that followed his murder — failed revolution, warlordism, civil war, invasion, renewed civil war — it is tempting to imagine that an assassin’s bullet had tipped China into a dark timeline. In a world where Song boards his train to Beijing instead of being gunned down on a Shanghai railway platform — and becomes prime minister — surely a better future was possible? Could Song have headed off the imperial ambitions of Yuan Shikai and enabled a successful transition to republicanism? A more stable central government could, at least in theory, have avoided the excesses that spawned the Communist Party in 1921. When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, Song Jiaoren would have presented a clear successor, and not one that would have swung to the right, flirting with fascism as Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) did. And it was Chiang’s anti-communist fervor that led to the rise of Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, whose path to leadership was opened by Chiang’s purge of the communists.

But counterfactuals are rarely simple, and the impulse to celebrate the dead — especially those who died young — can mislead.

Let’s return to that August morning in 1912: Song Jiaoren, the leader of his party, the face of China’s future, at the front of a crowd that had chosen him to lead them. One can imagine a rock-star-like atmosphere: thousands of enthusiastic supporters seeing their ambition for a parliamentary democracy coming to pass.

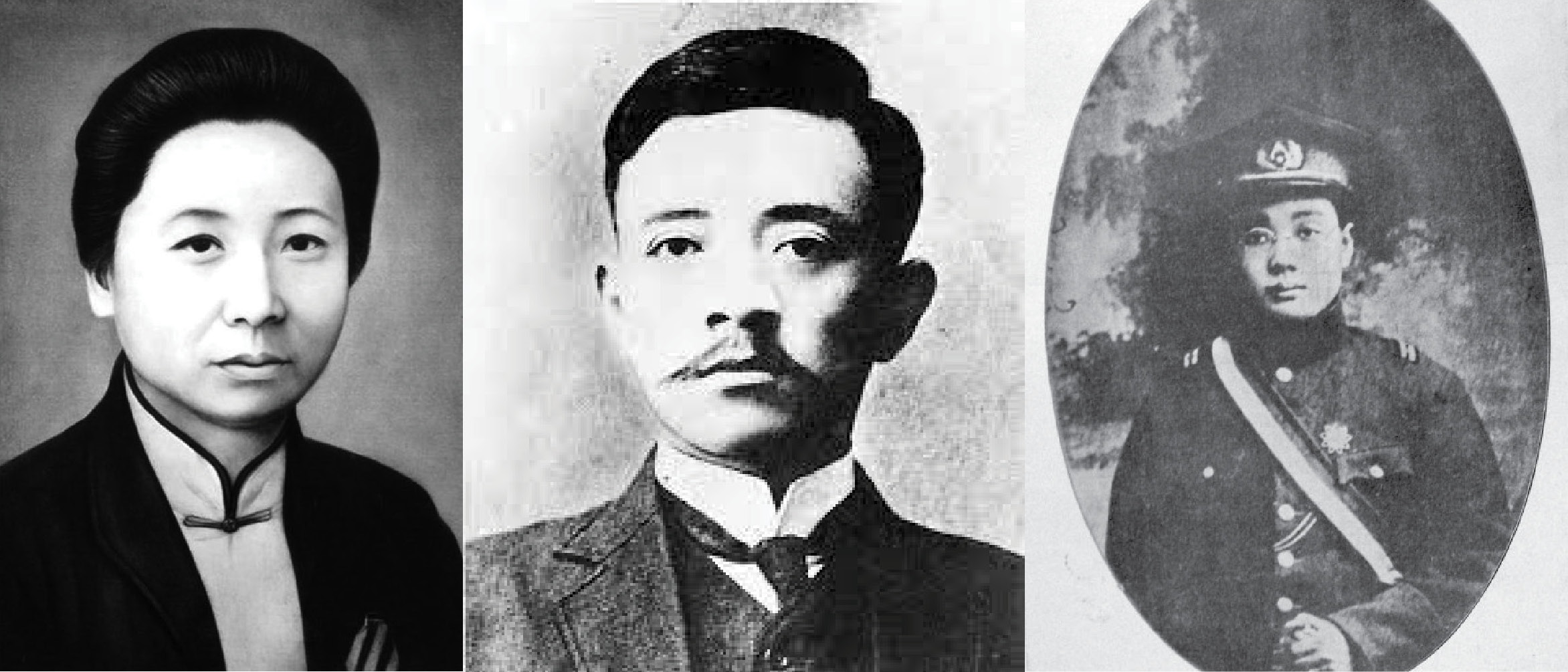

Instead, just after Song’s speech to the crowd, three women from the audience approached the stage and angrily confronted the men at the podium. Armed only with fans to ward off the August heat, the three women — Shěn Pèizhēn 沈佩贞, Wáng Chāngguó 王昌国, and Táng Qúnyīng 唐群英 — argued that the proceedings were making a mockery of the revolution and of democracy. Instead of celebrating Song’s leadership and promise, they heckled his cowardice and cynicism, and then they attacked him. As scholar David Strand described it in his book, An Unfinished Republic, “During the melee that followed, Shen and Tang slapped Song Jiaoren. Senator Lin Sen, standing next to Song, tried to mediate, and Tang struck him as well. Wang grabbed Song by the throat and threatened to shoot him. All three women were Revolutionary Alliance members and leaders of the Chinese suffragist movement. Their dramatic intervention left many in the audience ‘tongue-tied and staring in anger.’”

For women like Shen, Wang, and Tang, Song Jiaoren and the new Kuomintang did not represent progress or democracy or a modern society. Sun’s original organization, the Tóngménghuì 同盟會, or Revolutionary Alliance, had included in its platform a clause insisting on the equality of men and women, implying, if not guaranteeing, a right to vote. The Revolutionary Alliance had gained followers by appealing broadly to those with different grievances against the Qing and traditional society. Women like Qiū Jǐn 秋瑾 had been among the organization’s founders. In on the organizational ground floor of the movement, surely women would benefit once the movement had gained power.

But when the time came for a provisional constitution for the new republic, in March 1912, women’s suffrage was excluded. In protest, armed women stormed the legislative chamber, demanding a voice, in vain.

Women had been left out of the provisional constitution, but if the new government’s dominant party advocated for suffrage, there would be a path forward. The August convention was the chance to make that so. In her classic work, Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, historian Ono Kazuko described the scene: “From the very start, the floor of the conference was in an uproar over the issue of ‘equal rights for men and women.’” When chairman Zhāng Jì 张继 asserted that “it was only natural that voting rights for men and women not be equal,” the convention “fell into complete chaos…. In order to save the situation Zhang Ji took down a piece of paper on which was written in large characters ‘equal rights for men and women’ and he asked the entire assembled body whether this item should be included in the party program.” The resolution, Ono writes, “was buried by an overwhelming majority.” Of the 3,000 to 4,000 delegates, perhaps 50 were women.

Song Jiaoren’s priority was pragmatism at the expense of progress. As Strand writes, “Song Jiaoren was intent on transforming the Revolutionary Alliance from a violent, conspiratorial organization dedicated to overthrowing the now-defunct monarchy into an open parliamentary party suitable for a new and democratic republic.” In doing so, he sacrificed not only the commitment to women’s suffrage and women’s equality, but also commitment to “the people’s livelihood” (adopted as “policy” rather than “principle”) and “international equality.”

If there is an American analogy to Song Jiaoren, it is JFK: young, charismatic, popular, promising a new era. And, as we know, both gunned down as their careers were still new. And just as memories of JFK tend not to dwell on the corruption of his election, the Bay of Pigs, or escalating American involvement in Vietnam, Song Jiaoren is remembered as a charismatic democrat who opposed authoritarianism, not for reneging on promises in the naive hope that he could build an electoral coalition.

Denied equal citizenship, Tang Qunying and Shen Peizhen went the next day to Sun Yat-sen’s home, where he reaffirmed his personal commitment to women’s rights and gender equality, but also his helplessness in the face of popular opposition to this view. Strand writes that Shen and Tang “left the meeting unsatisfied and furious.”

Sun Yat-sen wrote to both women in the following days. He advised, “Never depend on men to act on your own behalf and never let yourself be used by men.”

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column. A correction: A previous version of this article included the phrase “late scholar David Strand,” though Strand is very much alive.