This Week in China’s History: October 1912

Great Bai Lang; Bai Lang is great!

He robs the rich, helps the poor and delivers Heaven’s fate

Everyone agrees, Bai Lang is great!

This folk song, translated by scholar Elizabeth Perry in her book Challenging the Mandate of Heaven, captures popular views of what some call China’s last great peasant rebel: Bái Láng 白狼 — literally, the White Wolf — whose army challenged the new Republic of China in its infancy.

The circumstances of rural north China had made banditry endemic by the early 20th century. A cycle of natural disasters, bad harvests, rapacious landlords, and ineffective local officials left villagers feeling alienated and desperate. Local strongmen could easily win followers by offering revenge or relief, especially if they could manage some guns and charisma. Operating outside the law, these men would get the somewhat romantic label “bandit” once they attracted the attention of the authorities (the essential English source on Chinese bandits remains Phil Billingsley’s 1990 Bandits in Republican China).

The Republic promised to sweep away China’s feudal system, empowering the weak and turning an ossified social system on its head. But in rural Henan province, villagers grew impatient with the pace of change as their cycle of misery showed little signs of relenting. If anything, 1912 was even worse than usual, as drought and flood alternated with grim irony; the ranks of the disaffected swelled, and provincial authorities, struggling already to implement a new government, now faced a surge of banditry that threatened to undo the new republic before it had even begun.

Facing this threat, the authorities turned to what Perry terms an “age-old tactic of Chinese rulers,” offering the bandit leaders office and rank in the new government in return for renouncing their rebellions ways. Local officials promised not only positions in government but cash money if the brigands would give up their criminal ways. Eighteen men accepted the bribes and turned up in Lushan expecting riches and recognition in return for their surrender. Instead, Perry writes, “the government turned on the surrendering chieftains and executed all of them on October 18, 1912.”

If Bai Lang had been more prominent, he might not have survived the “red wedding” at Lushan. Instead, with most of his competitors dead, Bai Lang attracted the disaffected and desperate to his cause. He had just a few dozen men under his command early in 1912; by the end of the year he had more than 600, based in the natural fortress of a gorge near Lushan. Within two years, his army had grown to 10,000 or more.

The “White Wolf’s” origins — the Western press couldn’t resist using the translation of his name once he achieved international notoriety — were unremarkable. Born in 1873 into a wealthy rural family, he had only one sibling — a sister — and perhaps this helped concentrate the family resources to enable a private education (though Perry notes that he dropped out after a short time and was barely literate). He worked as a farm laborer, married, and raised a family, supplementing his income by driving a salt cart for the government monopoly.

Bai Lang’s life turned sharply in 1898, when he killed a local landlord — apparently by accident — in a quarrel and was imprisoned for more than a year. Eventually freed at the cost of half of his family’s land, Bai Lang enlisted in the Beiyang Army for a short time. Then, in the chaos surrounding the 1911 Revolution, he turned to banditry, establishing a name for himself in the spring of 1912 when he and two dozen followers captured a local magistrate’s son and a cache of automatic weapons.

Happily for Bai Lang, he remained obscure enough to avoid the October 1912 purge, but after that he was the undisputed leader of outlaws in central China. From the summer of 1913, when he captured American missionaries in Hubei, he regularly raided cities across the region, from Henan and Anhui to, by early 1914, Shaanxi and Gansu. His armies continued to grow in size, fueled by policies like opening prisons or offering deserters from the government double their salary if they would join him. One press report from February 1914 asserted that 1,000 government soldiers had killed their commanding officers and deserted to the White Wolf.

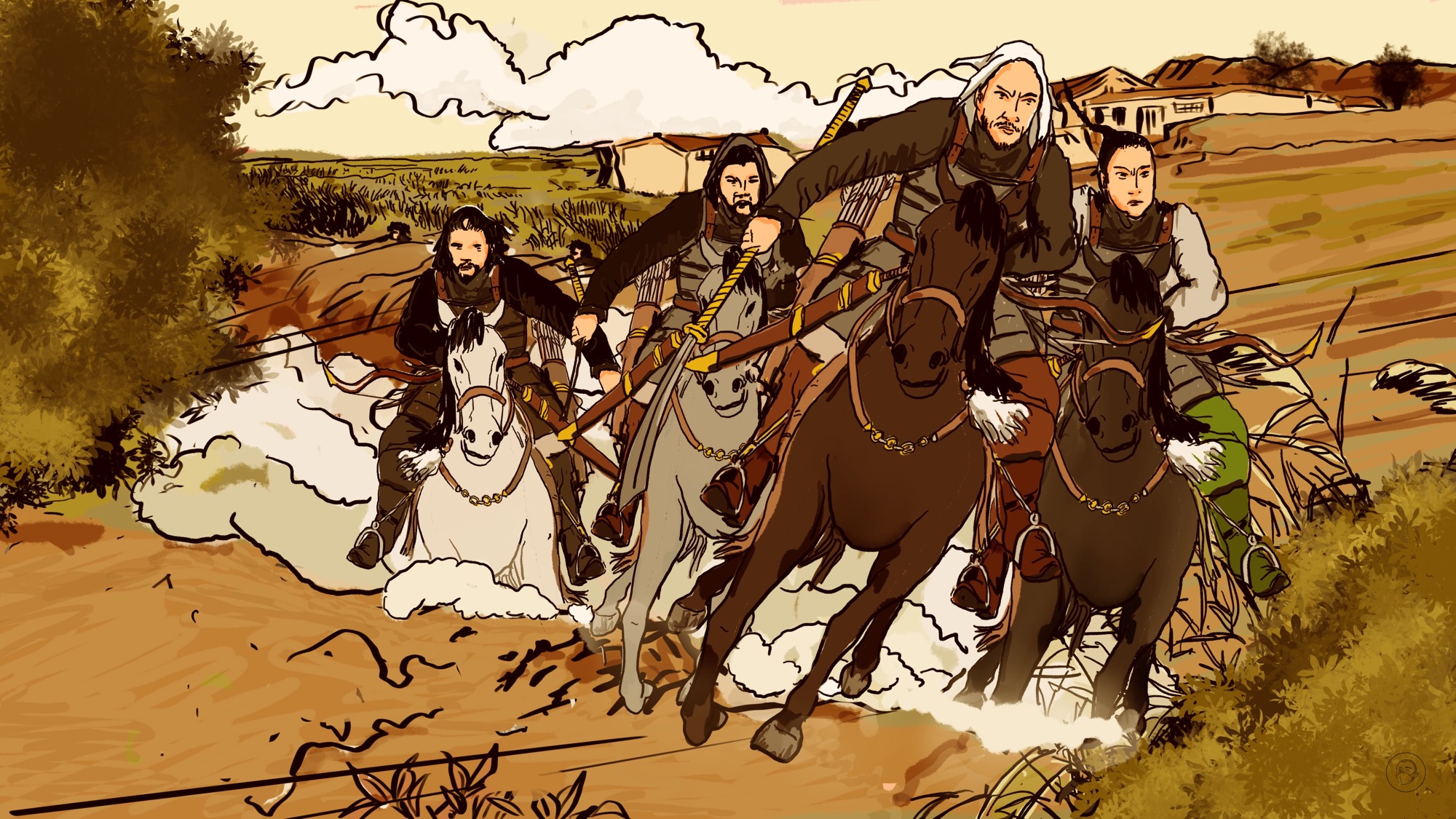

“A dashing figure,” according to Perry, “in a white fox hand and leather jacket,” Bai Lang became a celebrity as he rode at the head of a bejeweled cavalry stalking across the plains of central China. Accompanying this romantic image, Bai Lang gained a reputation as a Robin Hood figure, as the rhyme at the start of this piece suggests. Reports spread that Bai Lang stole and redistributed grain to help those suffering from famine, or that he showered the streets of a town with copper coins that he had stolen. In another story, he donated 2,000 taels of silver to buy books for a Gansu village school. Without doubt, Bai Lang could be violent, but his supporters insisted that his violence only targeted those in power. Perry records one attack in Anhui where, “although more than 500 persons were killed in the offensive, the casualties were predominantly officials — yamen runners, wealthy merchants, landlords, and money-lenders. Bai Lang had issued specific orders to spare coolies, artisans, cripples, and anyone who had participated in anti-warlord agitation.”

Of course, there was another side to the story. Foreign journalists brought the White Wolf to newspapers across the world. The Washington Post wrote in the spring of 1914 of “outrages by brigands” in which “bands associated with the noted outlaw White Wolf are ravaging various sections of the country, ruthlessly murdering and robbing the people and burning their property.” No Robin Hood here.

At the peak of his movement, the White Wolf commanded more than 20,000 troops and ranged across five provinces. By the summer of 1914, though, his fortunes had changed. In Gansu, he faced not only government troops but an outbreak of plague and the wrath of locals after his troops killed a Muslim governor. The anti-Muslim actions of Bai Lang’s forces were constant, peaking with a massacre in Taozhou, Gansu, that galvanized local resistance to him. Now hunted by both the government and the people, the White Wolf became increasingly desperate; he rejected proposals from his advisors that he a) declare himself emperor of a new dynasty, or b) revive the recently fallen Qing. His troops differed over next steps, and his army splintered.

It was back where the rebellion started — in the hills around Lushan — that it met its end. Bai Lang was wounded in a battle in August and returned to his home village in Henan, where he died. (In another version of the story, presented in the pages of Shanghai’s North China Herald, “White Wolf and a few of his most faithful followers tried to escape disguised as farmers. Near Lushan…White Wolf was recognized and seized, and his head hacked off.”)

Rumors of White Wolf’s death were common, so it was not until his head was placed on a pole outside the Kaifeng city wall — where it was identified by his daughter — that the government declared itself finally rid of, in the words of the North China Herald, “a common pest from whom China has suffered for far too long.”

Whether “a common pest” or China’s Robin Hood, Bai Lang led the last of China’s great peasant rebellions, taking China’s Republic to the brink.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.