A dyslexic learning Chinese

English text and roman letters swim around on the page, but Chinese characters are bright and clear for Lee Moore.

I am a native English speaker, but it was only while studying Mandarin that I noticed the first signs of my dyslexia.

Long before I began studying Chinese, my weaknesses in reading English had always been covered over by my other strengths. By the age of six, I was in the gifted class, but reading aloud terrified me. I frequently found words floating from one line to the next. None of my teachers ever commented on the problem; I kept my grades high, and offset my reading skills with other strong points.

As I grew older, I became skilled at weaseling my way out of problems occasioned by my dyslexia. Like many dyslexics, my disability was not caught until fairly late. As Sally Shaywitz, in her book Overcoming Dyslexia, points out, “In fact, it is not unusual for dyslexics to go unrecognized until adolescence or adulthood.”

Before I knew I was dyslexic, I had already spent two years in China studying Mandarin and gotten a Master’s degree in comparative literature at the University of Georgia. My troubles reading English rarely manifested themselves in my readings of Chinese. If anything, I noticed that I was a tad faster when reading alongside classmates at the same level.

One struggle I did have in learning Chinese was distinguishing the pronunciations of words that, in pinyin, had easily reversible spellings: zhuo and zhou, shuo and shou, nei and nie, lei and lie. No matter how much I tried to memorize them, I frequently misremembered the pinyin, reversing one vowel for the other. Intending to say to “receive” (受到 shōu dào), what often came out of my mouth was the word “to mention” (说到 shuō dào). No matter what I did, I could not learn the pronunciations of these words, and I recognized that, when reading the pinyin, I frequently found the “o” and the “u” or the “i” and the “e” floating back and forth.

The alphabet is the problem

But in 2013, I went to Taiwan, where they do not use pinyin or roman letters to teach elementary schools students and foreigners how to pronounce Chinese words.

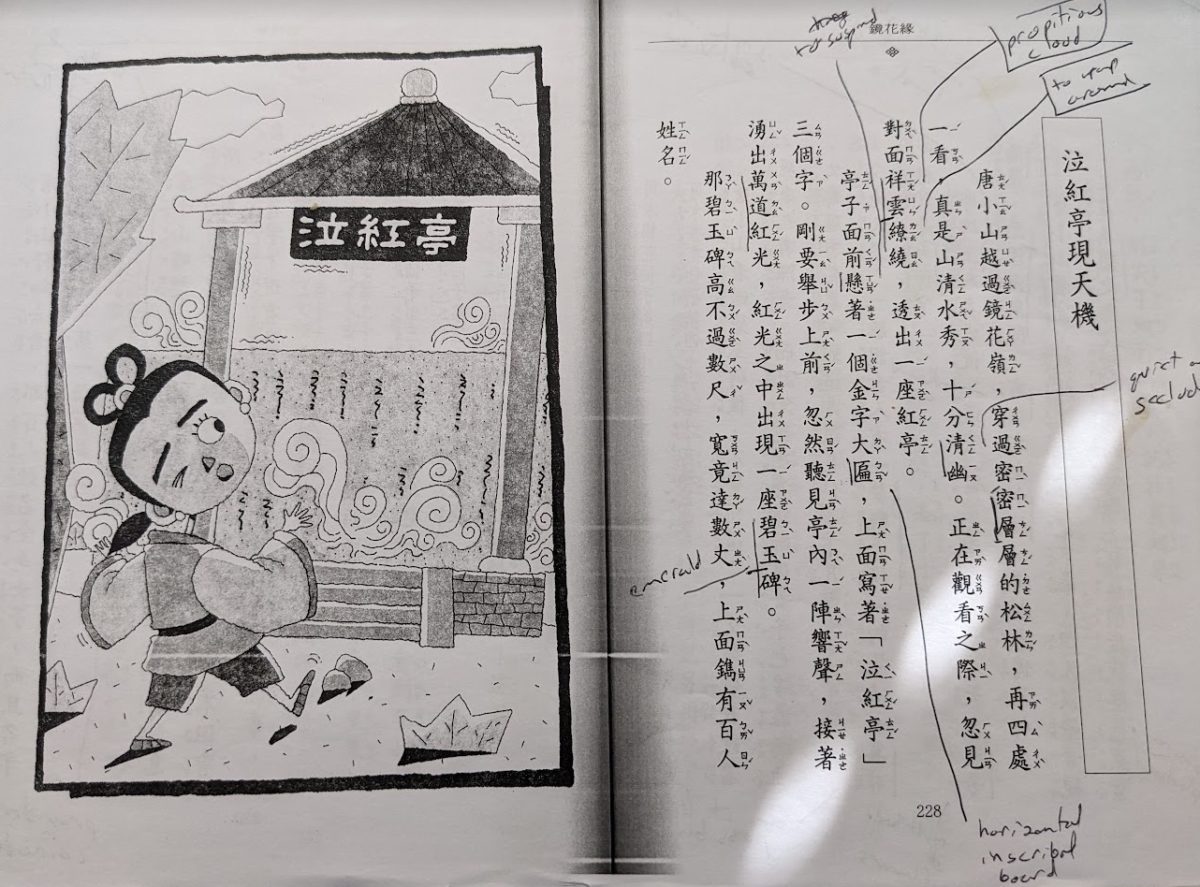

Late that year, almost midway through a year-long scholarship studying in Taiwan, I began to read young adult editions of classical Chinese novels, to pass the time in Taipei’s soggy winters. For language learners, these young adult editions are an excellent resource. They narrate the Chinese classics in a simplified language, and, printed beside each Chinese character, was its pronunciation, spelt out in bopomofo, which is the Taiwanese system for rendering Chinese into a phonetic system.

Though officially called Zhuyin Fu Hao (注音符號 zhùyīn fúhào), bopomofo is the name almost universally used for the phonetic system. It functions similarly to pinyin, though it looks very different because it is based on the ancient Small Seal Script (小篆 xiǎozhuàn). So, the Mandarin word for “encyclopedia” — 百科全書 in Chinese characters — is bǎikē quánshū in pinyin but ㄅㄞˇ ㄎㄜ ㄑㄩㄢˊ ㄕㄨ in bopomofo.

As I learned bopomofo, I started to connect the floating pinyin with my floaters in English, and recognized that I might be dyslexic. With bopomofo, there is no muddling through which comes first, the “i” or the “e,” the “o” or the “u.” For example, the word “to talk about, to mention” 说到 is transliterated into ㄕㄨㄜ. The word “to receive” 受到 looks fairly different: ㄕㄡ. Though the initial consonant is the same, the vowels in the two words are completely different and not easily transposed.

As I was plowing through the young adult edition of Flowers in the Mirror (鏡花緣 jìnghuā yuán) by Lǐ Rǔzhēn 李汝珍, I noticed that the trouble I long had in remembering vowels in pinyin disappeared in bopomofo. Of course, I had heard that dyslexics switched letters around, but I had never linked that to my pinyin problems, nor to my problem in English of words floating from line to line. But seeing how much easier bopomofo was for my brain to make sense of, I grasped that they were probably related.

This first inkling that I might be dyslexic changed little in my life. I was in Taiwan, and had no time for worrying about my English reading skills. But two years later, another incident in Taiwan prompted me to think more seriously about getting a dyslexia diagnosis.

Reading Chinese upside down

In 2015, I completed my first year in the University of Oregon’s Chinese literature Ph.D. program and returned to Taipei on a new scholarship to work on my reading skills. In a one-on-one session with my teacher, we were reading Half a Lifelong Romance (半生緣 bànshēng yuán) by Zhāng Àilíng 張愛玲, with her correcting my mispronunciations and answering my questions about the text. Zhang’s novel was open before both of us, and we were elbowing into each other’s personal space as I tried to read and she tried to watch me read. Finally, my teacher suggested I turn the book so that it was right-side-up for me and upside down for her. “I have been teaching foreigners to read Chinese for years. I am sure it is easier for me to read upside down than it is for you,” she said.

“What’s so hard about reading upside down?” I asked, flipping the novel over and reading the Chinese to her almost as smoothly as I had read it when it was right-side up.

“Huh,” she mouthed, astonished. “I have never seen a native speaker of Chinese read upside down so well, much less a non-native speaker.”

The incident swirled around in my head for the rest of the summer. How could I, a slow reader in my native tongue, outperform native speakers of Chinese in upside-down reading skills? An admittedly weird skill, but a skill nonetheless.

This incident prompted me to seek out solutions for dyslexia. At the recommendation of my wife, my first move was to install audiobook apps on my phone, such as Audible, Hoopla, and Libby. Before this, I had read an average of 30 to 50 books a year, with 2015 being an average year when I knocked off 41 books. In 2016, when I first began ear reading (yes, it is a word, get over it, see Dyslexia Empowerment Plan by Ben Foss) audiobooks, that number creeped up to 57 books. The next year, it inched up to 70 books. In 2018, the number of books I read leapt to 172, and in 2019, I hit 233. By 2020, I was reading, on average, a book a day, a pace that I have maintained since.

It was these two events in Taiwan that prompted me to begin the process of getting a diagnosis, something I got in 2019. Had I not had these Chinese-learning experiences, I might not have even realized I was dyslexic at all.