Q&A: Director Violet Du Feng on ‘Hidden Letters’ and cross-generational resilience of women in China

The China Project sat down with Shanghai-born, Emmy-winning independent filmmaker Violet Du Feng to discuss her latest documentary, Hidden Letters, which shines a light on how modern women in China keep alive the tradition of Nüshu, a coded, once-secret script emblematic of Chinese female empowerment and sisterhood.

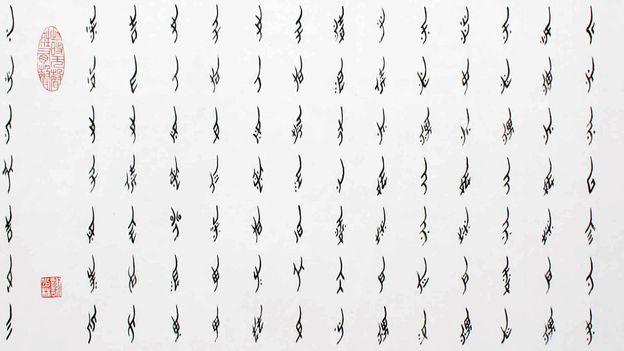

Nǚshū 女书 — literally, “women’s writing” in Chinese — was a coded script developed and used by peasant women in a remote village of Hunan Province during the 19th and 20th centuries. At a time when many Chinese women were denied literacy and foot binding was prevalent, the secret language of Nüshu, often written on tiny items and fabrics such as quilts and handkerchiefs, emerged as a way for socially isolated women to maintain bonds with female friends in different villages and express themselves freely within the confines of a patriarchal society.

Believed to be the world’s only language to be invented and used solely by women, Nüshu was declared extinct in 2014, when its last surviving user, Yáng Huànyí 阳焕宜, passed away at the age of 92 in Hunan. However, the defiant spirit of the clandestine script remains a source of inspiration for many of its modern practitioners who aspire to keep the tradition alive.

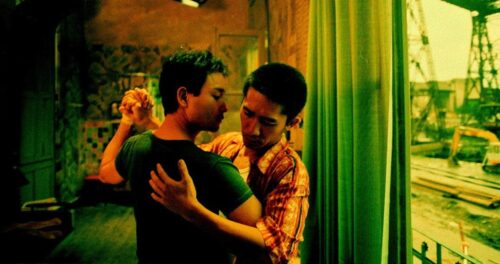

Nüshu has been the subject of multiple media projects throughout the years, including Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, a 2011 historical drama film. The latest work to shine a light on the ancient language is Hidden Letters, a 2022 documentary by Shanghai-born, Emmy-winning independent filmmaker Violet Du Feng (冯都 Féng Dū).

Featuring two millennial practitioners of Nüshu who find solace in the language while facing systemic sexism in today’s China, Feng’s film is a thoughtful and timely exploration of Nüshu’s history and its lasting impact on contemporary Chinese feminism, which is not simply an inheritance of Western ideas and has been under attack by the central government for challenging China’s highly patriarchal political system.

Hidden Letters received positive reviews at the Tribeca Film Festival earlier this year, and will hit theaters in the U.S. starting on December 9. You can find more information on screenings here.

Ahead of its theatrical release, The China Project spoke with Feng about the documentary.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to make a film on Nüshu?

I learned about Nüshu around 2005 when I read a novel called Snow Flower and the Secret Fan by Lisa See. The book is based on Nüshu and I was really blown away by it. It talks about that particular history that I knew nothing about as a woman born and raised in China. At the time, I was in the U.S. making documentaries and I felt kind of embarrassed and ashamed that I didn’t know much about Nüshu. I thought about adapting it into a movie, but it turned out that Wendi Deng had already purchased the rights to the book.

Fast-forward to a few years after that. I moved back to China, got married, and became a mother. It was during that time that I started to feel this sense of pressure from society, from everywhere that I didn’t feel before as a woman. I realized how societal changes had affected gender equality in many ways in China. For example, the gender income gap has widened because of capitalism and the market economy, which has affected women because they make less money and are expected to function more in family roles. But at the same time, their contributions to the family are not valued fairly and properly. I also felt that Chinese women didn’t have as much protection legally, financially, and culturally as their peers in other parts of the world. In Chinese culture, there’s also this ingrained impression of what women’s roles are as a mother, a wife, and a daughter-in-law. For me, all of those feelings sort of exploded internally because I was at that point of my life where I had to figure out how to fulfill those expectations.

I also felt it was very different from the time when I grew up, which was more or less during the communist time. My mom’s generation benefited tremendously from the communist promotion of gender equality. She was the first medical professional in my family and made an equal amount of money as my dad. I was actually mostly raised by my dad, which he never complained about. He also always pushed me to pursue my dream, which made me feel that there’s no limit to what I could accomplish as a girl.

After I returned to China, all the responsibilities and pressure just overwhelmed me, making me feel very confused as to what it means to be a woman, especially in today’s China. Without a state-backed child care system, I had to stay at home to take care of my daughter. All of a sudden, me having a career and trying to accomplish things professionally didn’t matter to anybody in the society.

I started to have conversations with a lot of my girlfriends and then realized that everybody was in the same boat. That was around the time when my two producers came to ask me to make a film about Nüshu. My instant reaction was that I knew the context of how Nüshu was created, why these women created that, and what Nüshu means as a legacy to these women. I asked myself if there is a way that I could connect that story to women’s experiences in modern China. That’s why I started the process of trying to frame this film while doing research to understand what the contemporary component of Nüshu is and if it still exists in China today.

When did you first start working on the documentary? Did the pandemic affect the filming at all?

We started officially filming in December 2017 and wrapped up toward the end of last year.

I thought the pandemic would affect our filming in a tremendous way because everything stopped, but it actually didn’t. We started filming in 2017, all the way to when the pandemic broke out, and at that point, my co-director and I were following two main characters.

But at a certain point, I was even thinking about casting another character, who is a Chinese Australian. She grew up as a feminist but also has to deal with a lot of issues regarding gender roles. When she moved to China, she stumbled upon Nüshu and created a workshop where participants could talk about Nüshu and its legacy. She also used this workshop to teach other young women in China how to be a DJ because that’s an industry predominantly controlled by men.

I thought that was really fascinating because she represented a different voice. I tried to cast that person, but for a long time, she was stuck in Australia and couldn’t go back. At that moment, I didn’t have that much to do, and then the shooting in China stopped, too. I said to myself, “Okay, why don’t I take this time just to start revisiting all the footage?” It took me months to do that and by the end of it, I realized that I already had enough to make a film. The film was actually completed a year earlier than I had expected.

How did you find the film’s key figures?

I knew that I wanted to cast people from the millennial generation as main characters for the documentary. My focus was to find someone who was trying to practice Nüshu and revive Nüshu in their own way. My casting pool was very small because here were only seven certified practitioners of Nüshu.

One of my main characters is Hú Xīn 胡欣, a tour guide and educator in the Nüshu museum in Jiangyong County. She has a really positive story that without Nüshu, she would have just been a farmer. Nüshu really elevated her to a degree that she became a national face of the language, in part thanks to support from the local government. But I wasn’t sure whether she could be my main character until at the end of a conversation I had with her, where she hinted to me in a way that I started to sense something because she was saying that she was worried that there’s nobody else who can take over her torch. She said, “What if I have a son? Then I’ll have to take care of my son. Now who’s going to do Nüshu?”

I started to wonder why she had that kind of concern. Because, first of all, why does it have to be a son? And second, why can’t she continue to do her job after having a child?

Besides her, I knew I wanted to cast somebody else in urban areas because I wanted to shine a light on the unique challenges faced by women in urban settings. Through Hu Xin I met Simu, who actually learned Nüshu from Hu Xin and was living in Shanghai at the time. She’s a music teacher and her parents were very supportive of her career. They really cared about her professional success and she took it very seriously, too. What I love about her is that she has this pure passion about Nüshu compared with everyone else who’s trying to profit from it. She really was hoping to have a dialogue with Nüshu users in the past through the language to help her understand more about her gender roles in today’s China. Moreover, she was in a relationship. I thought it would be interesting to explore those aspects, to see the gender dynamics between how she sees herself and how others see her as a woman. Another interesting thing is that she is involved in an annual female artist exhibition, where participants use different kinds of art forms to express their feminist voices.

Was it difficult to convince them to be part of this film?

I don’t come from a sort of Western perspective to look at them. We built a relationship based on empathy. They knew that I was making this film that’s not necessarily about Nüshu, but really about them because they are representative of the women who are in the same situation. And I’m also one of them. That’s how I think that we have that kind of trust. I share with them my previous films. One of them is called Please Remember Me and it’s about elderly care in China. It’s a beautiful documentary where I try to humanize the people I interviewed and change the stereotypes of Alzheimer’s in China.

I don’t necessarily believe in an anti-China approach or anti-government approach. I don’t think that’s what this film is really about. It’s much more complex than that. As a Chinese, I believe that change has to happen from within and it’s important to deal with issues in a gentle and nuanced lens and to provide perspectives about China that are different from what the Western mainstream narrative is about.

That’s why in Hidden Letters, I’m very intentional that I don’t want to make any antagonists. For example, I don’t want to make the government an antagonist because it’s very easy to make any story about China with the government being a scapegoat. I also don’t want to make men antagonists because I wanted to show that they’re also stuck and trapped in their own cultural and social expectations in a lot of ways.

What were the biggest challenges of creating this film?

There are a couple of things. One of the challenges is how I could embed my pretty radical subversive perspectives into it, but in a gentle and nuanced way. How to create my boundaries? How do I know how much I should push forward? When is it necessary for me to pull back? I filmed some more radical moments, but eventually I decided not to include them in the film. Partially that’s because I’m trying to protect my subjects, which is a standard practice when you make a film about China.

Another main challenge is how to tell a cohesive story and make the film flow organically. Because Nüshu is such a rich topic that spans the past and present, it takes very specific spacing of this film in order to make everything work.

Do you consider yourself a feminist? In your opinion, how does Nüshu speak to Chinese feminism?

I have a different approach of being a feminist because I’m Chinese. I don’t necessarily feel that the Western way of feminism — the sort of creating protests and overthrowing the system — will work in China. For me, I think the Eastern way of feminism is to create a sense of sisterhood so that we can have a space to be honest with each other, sharing our vulnerabilities and how we feel.

As modern-day Chinese women, we are actually taking in a lot of expectations and we fulfill all of them because we are so strong and capable. But I feel like the more that we’re projecting to the outside that we’re actually strong and tough, we’re super, the more we’re suppressing on the inside that this is actually too much for us to handle. I believe in the Nüshu way of being able to say that we’re enough and this is suffering and this is unbearable. A lot of Nüshu poems are used as a way of expression, to complain about unfair treatments and sufferings.

Sometimes those authors feel they’re very pitiful in a way, but it’s also like, it’s a space for them just to vent it out and then to share their honest selves. My belief is that strength and power could be created from within as a community if people are vulnerable with each other and supportive. I think for Chinese women, the most important thing is for us to build our strengths from within. Only by doing that will we see how the narrative is being changed and how the outside perceives us differently.

What do you hope viewers take away from this film?

For female viewers, I want them to feel loved and I want them to feel heard and seen. I want them to feel empowered at the end. Nüshu will eventually die out because we already lost the function of the language. But Nüshu is not just about the language, it’s about the legacy and essence and the spirit of it. And to me, the spirit of it lies in how it allows us to be vulnerable, to share stories about our injustice and suppression, to create an intentional space of sisterhood, and most importantly, to inspire us to rebuild our resilience and power and pride as women.

The legacy of Nüshu should not only exist in China. Rather, it’s for a wider audience. I want people across the world to know about Nüshu and that’s how it will thrive and continue to live on as a code of defiance.