Chinese ceramic artist contemplates permanence and loss through delicate pottery

Peng’s ceramics are delicate and fine, only a few millimeters thick. His bowls possess a lightness or airy quality that seems to lift them off the ground—an effect he often achieves by combining a flared rim with a narrow base.

This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

When Péng Chéng 彭程 sat down for the first time at a potter’s wheel, something felt right. It was 2014, and he was working at iLook magazine in Beijing. As part of a special feature on millennials working in traditional handicrafts, Peng traveled to Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of China, to interview young ceramic artists. A friend who ran a ceramics shop in Beijing made some introductions, and he quickly met and got to know a handful of artists for the feature. Later that year he decided to return.

“Over the October holiday I went to Jingdezhen to visit them, and one of them, Luo Xiao, persuaded me to try throwing a bowl,” he recalls. “I quickly got the hang of it, and the clay didn’t feel at all unfamiliar to me.” Back in Beijing, he continued practicing his new hobby, which was quickly becoming an obsession, and in late 2016 he decided to take a year off to devote himself wholly to ceramics.

Now Peng lives in Shanghai, where he works in communications at the fashion brand Icicle. Pottery is mostly relegated to weekends and days off. Yet that hasn’t slowed him down: he still finds time to go to his local studio, PWS Shanghai, to throw, decorate, glaze, and fire bowl after bowl. Dozens of his works were on display at his 2020 show Linger at the ceramics gallery Chinale.

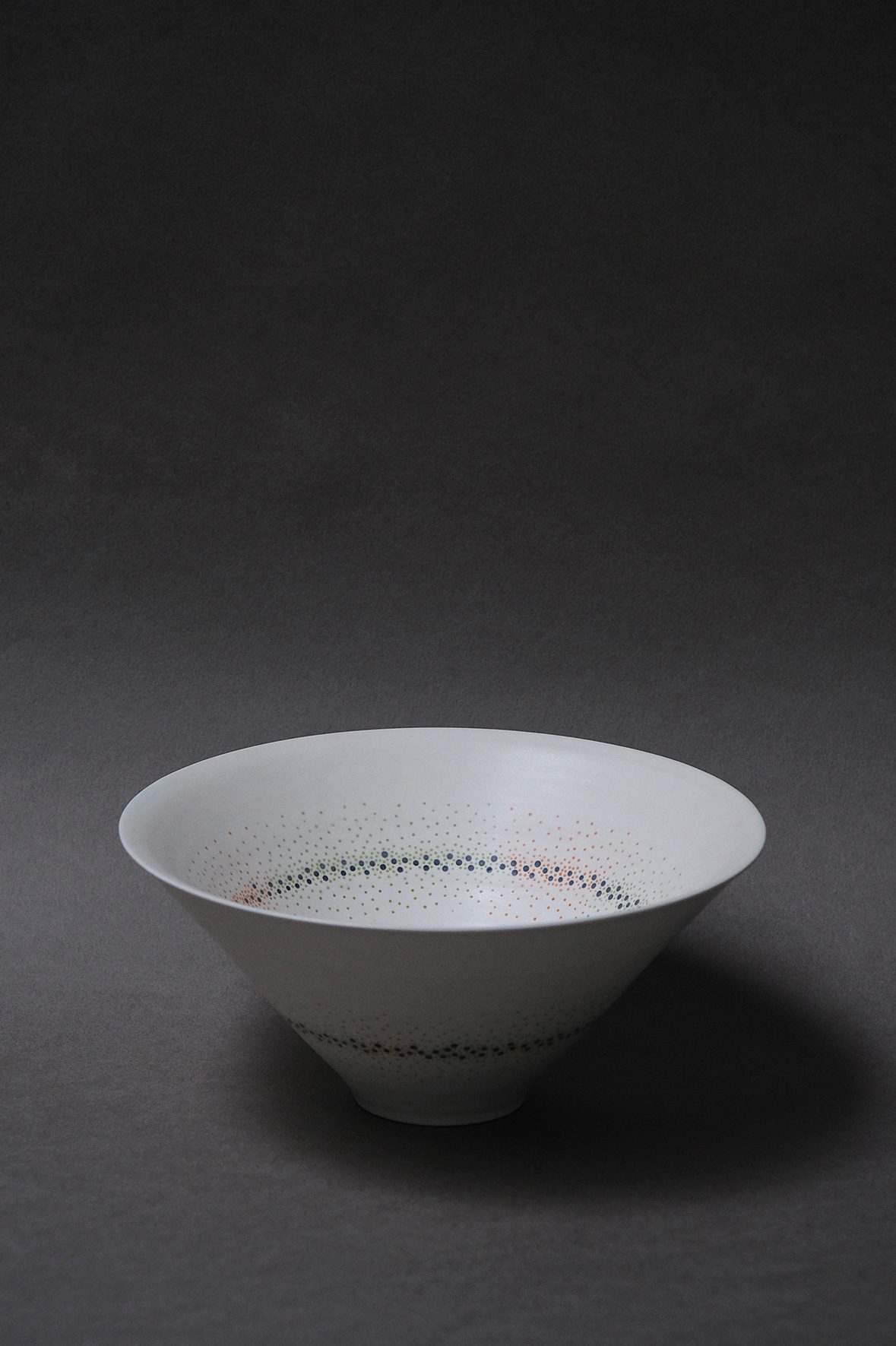

Peng’s ceramics are delicate and fine, only a few millimeters thick. His bowls possess a lightness or airy quality that seems to lift them off the ground — an effect he often achieves by combining a flared rim with a narrow base. You almost expect them to tip over, yet they still exude a certain fragile confidence. “I like simple vessels that nevertheless have a strong formal sense — strong but not aggressive,” he explains. “I also like unstable forms, a sort of teetering aesthetic. So many of my bowls are not especially practical, though practicality is not what I’m after.”

This particular teetering or “wobbly” aesthetic owes a good deal to the influence of Lucie Rie, a twentieth-century Austrian potter whom Peng considers an idol and an inspiration. His high regard for her work even led him to translate her biography by Tony Birks for New Star Press.

Peng’s decorative patterns are simple rectangles or lines of inlaid color — never drawings or images. “In my opinion, good decorative techniques are achieved using the essential plasticity of the clay, so I opt for engraved lines and dimples, which I then inlay with liquid clay of a different color.” Adding a painted design or image would mean treating the vessel itself as a surface medium and ignoring its plasticity, something he refuses to do.

Exquisite as they are, these bowls are still unmistakably human: the lines and miniature holes show slight handmade irregularities, subtle evidence of their maker’s touch. Yet Peng doesn’t self-consciously attempt to assert his presence or create a rustic look. “For me, hand-crafting is a production method, not a style, so I aim for accuracy and avoid an easily visible ‘handicraft’ quality,” he says. “I let the hand-craftedness become a trace, naturally left on the works.”

Linger, which includes vessels that Peng made over two and a half years, comprises six distinct collections, each named after a different location in or impression of Kyoto: Golden Pavilion, Silver Pavilion, Moon River, Pale Water, Late Sakura, and Virgin Snow. “It’s the lingering thought of cherry blossoms falling, the lingering thought of virgin snow before it melts in your hand,” he explains.

Yet Linger is just the show’s English title. Its original name is 残念 — cannian in Chinese, though it’s actually a Japanese word, zan’nen, that means remorse or regret.

“I lived in Japan for two summers and studied Japanese. I really like that word,” Peng says. “You can say it whenever something disappointing, tragic, or unfortunate occurs, whether big or small. Literally, zan means remaining or unresolved, while nen carries the sense of remembrance. So zan’nen is an unresolved thinking about something that’s lost or gone.” Yet the word also carries a note of acceptance or resignation. “I think this word conveys a complex state of mind, a whole understanding of loss and gain, in fact.”

Peng grew up in Beijing and moved to the US for university. At Vassar College he majored in East Asian Studies, with an emphasis on Chinese and Japanese aesthetics, and in particular on the history of Buddhist art. Awarded a prestigious Thomas J. Watson fellowship for international exploration, he spent the year after graduation traveling the world, visiting England, Germany, Turkey, India, and Cambodia, among other countries, before returning to Beijing. Angkor Wat, where he spent a week, left an especially impression on him, as did the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul.

Given his background in Buddhist art, along with the philosophical name of his new show, you might expect Peng to find a spiritual dimension to working with clay. Yet he’s unequivocal on this point. “I’ve come to realize that when something has a so-called ‘spiritual meaning,’ that means it’s not fully integrated into your life,” he says. For him, working with clay is something altogether more ordinary. “Making pottery is like eating, sleeping, or breathing, an entirely natural part of my life.”

Still, pottery speaks to permanence and loss in a particularly eloquent way. As Peng likes to point out, pottery was one of the first things humankind invented that could last more than a lifetime. “Leather, wood, and rattan all follow nature’s cycle of life and death, yet pottery can be passed down from generation to generation. It gives people a sense of possession beyond time,” he explains. “And because you can only lose what you can possess, with pottery people also learned sorrow and acceptance. I find this very romantic.”

For now, Peng continues to work during the week and spend nearly every weekend on his art. He’s not sure what the future will hold, but he remains open. “My only hope is that, whatever changes occur in my environment or my lifestyle, I can keep doing this,” he says. “When you create a bowl, it’s not something you can plan. It’s a process that unfolds as you go along.”

Like this story? Follow neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

WeChat: pengcheng_ceramic

Contributor: Allen Young

Photographer: David Yen

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li

Additional Images Courtesy of Chinale