As Chinese urban professionals tighten their purse strings in the face of a slowing economy, an unassuming lunch option traditionally enjoyed by blue-collar workers in Northeastern China has become an online sensation.

For a long time, food content on lifestyle and social commerce app Xiaohongshu — often described as China’s answer to Instagram — was dominated by three types of posts: reviews of trendy restaurants, healthy recipes, and food diaries by office workers, all presented with a carefully staged and glossy-looking aesthetic popular on the platform.

It made perfect sense, as Xiaohongshu’s culture is all about promoting aspirational lifestyles — dressing up, traveling, and — of course — eating fine food.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

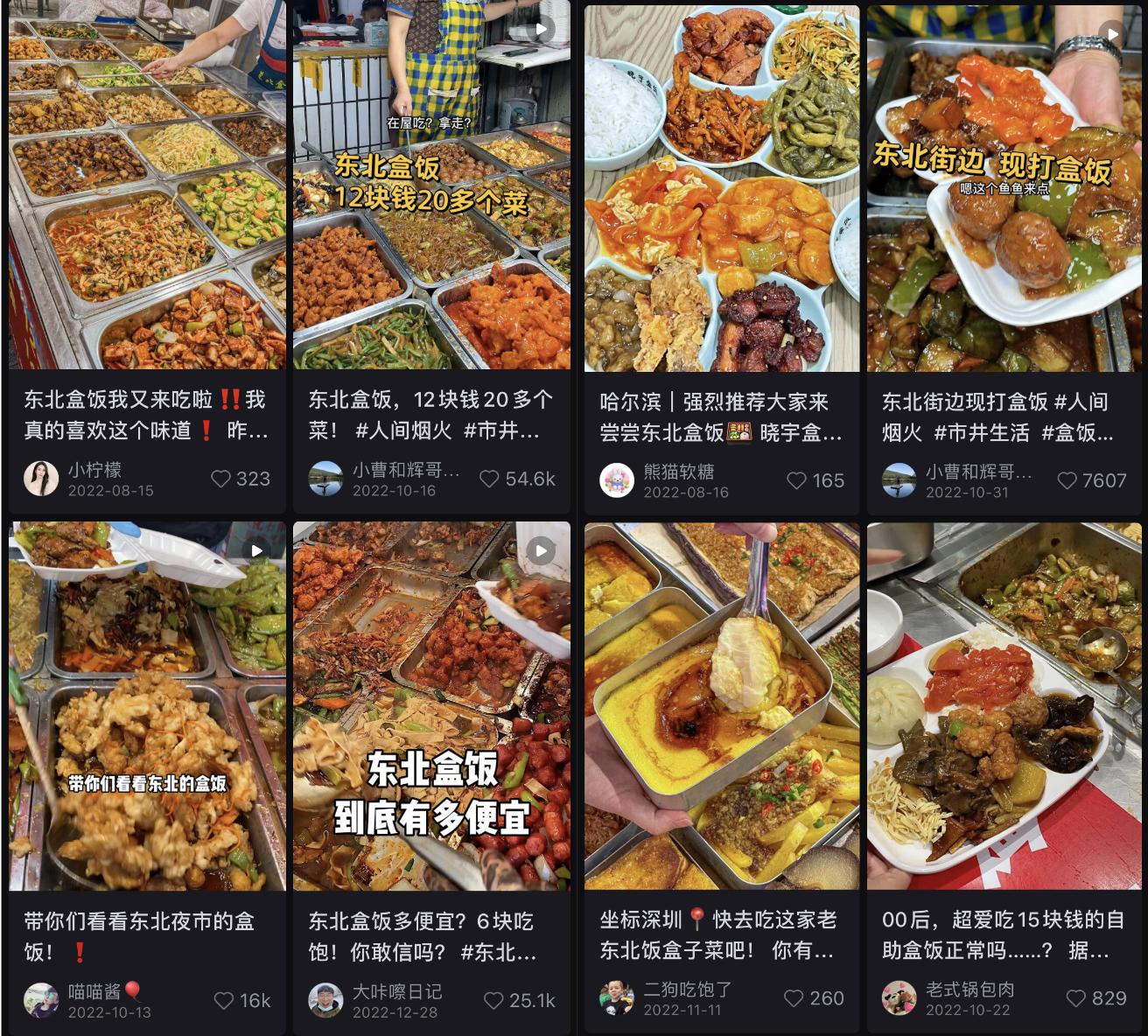

But about a month ago, a different type of food post took Xiaohongshu by storm. Countering the app’s fundamental ethos, the new trend centers “Northeastern lunch boxes” (东北盒饭 dōngběi héfàn), the kind of meal that’s ubiquitous on the streets of northeastern China but rarely seen in metropolitan cities like Shanghai and Beijing.

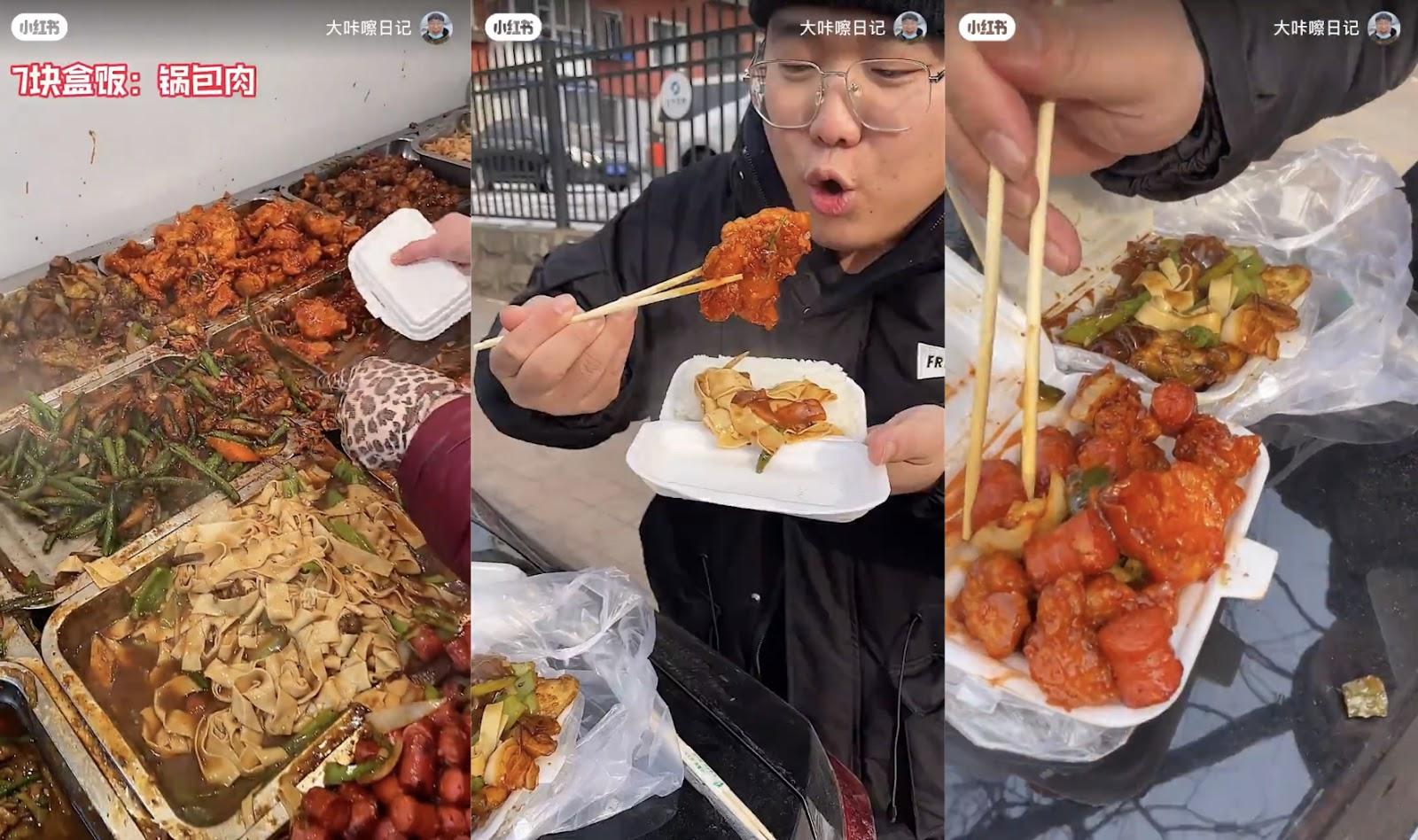

On Xiaohongshu, a search for “dongbei hefan” brings up tens of thousands of posts that collectively have millions of views. They include a string of videos by user Dà Kāchā Rìjì (@大咔嚓日记), a food influencer in Tieling, Liaoning Province, who frequently films himself visiting small food businesses and street vendors in his city. In a video posted on December 28, he shows a cafeteria-style hole-in-the-wall restaurant with a variety of food plated in steel trays. For 14 yuan ($2), the content creator bought six dishes — a mix of vegetables and meat — and two bowls of rice. “The main characteristics of dongbei hefan are huge portions and cheap prices,” he proudly states in the video.

The clip has garnered nearly 25,000 likes so far, and the comments are full of people saying they wish such food was available in their areas. “I’m drooling just by watching this video. I’m so jealous!” one person wrote.

One of Dakacha Riji’s followers is Mia Cao, an apparel sales representative in Shanghai, who described his videos as “the perfect digital appetizer” when she takes lunch breaks at her office desk. “Cheap food options are hard to come by not only in my neighborhood, but in Shanghai in general,” she told The China Project. “I’m so envious of the people in dongbei.”

What is dongbei hefan?

Dongbei hefan has long been a major staple in the diet of local people, enjoyed mostly by low- and moderate-income workers who live on a budget. Businesses providing dongbei hefan fall under two categories: restaurants in fixed locations, and mobile food vendors. The latter tend to have the cheapest deals, as they can save money on rent.

Dongbei hefan is popular mainly because of its affordability and diversity. For as low as 10 yuan ($1.49), customers can create their own meal plates with three dishes and their choice of starch. Options available often include sweet and sour pork (咕咾肉 gū lǎo ròu), stir-fried tomatoes and eggs (番茄炒蛋 fānqié chǎo dàn), and eggplant with garlic sauce (家常茄子 jiā cháng qiézǐ) — all homestyle, comfort food items that pair well with a bowl of rice.

In the comments to dongbei hefan videos on Chinese social media, a question that pops up frequently is how vendors actually make a profit when the prices are so low. But according to Zhāng Yúfēi bùshì Zhāng Yúfēi (@章余飞不是章鱼飞), a food blogger who has 1.45 million followers on video-sharing site Bilibili, one of the most popular dongbei hefan restaurants in Harbin is able to pull in an average of 30,000 yuan ($4,475) in sales per day. So the profit margins might be small, but there’s enough revenue to make the business work.

Additionally, insiders have commented on social media that not having to pay building rent or deal with the upkeep of a dining room are the primary money-saving advantages for many dongbei hefan providers. And in comparison to first-tier cities like Shanghai and Beijing, food prices are relatively lower in the northeastern part of the country.

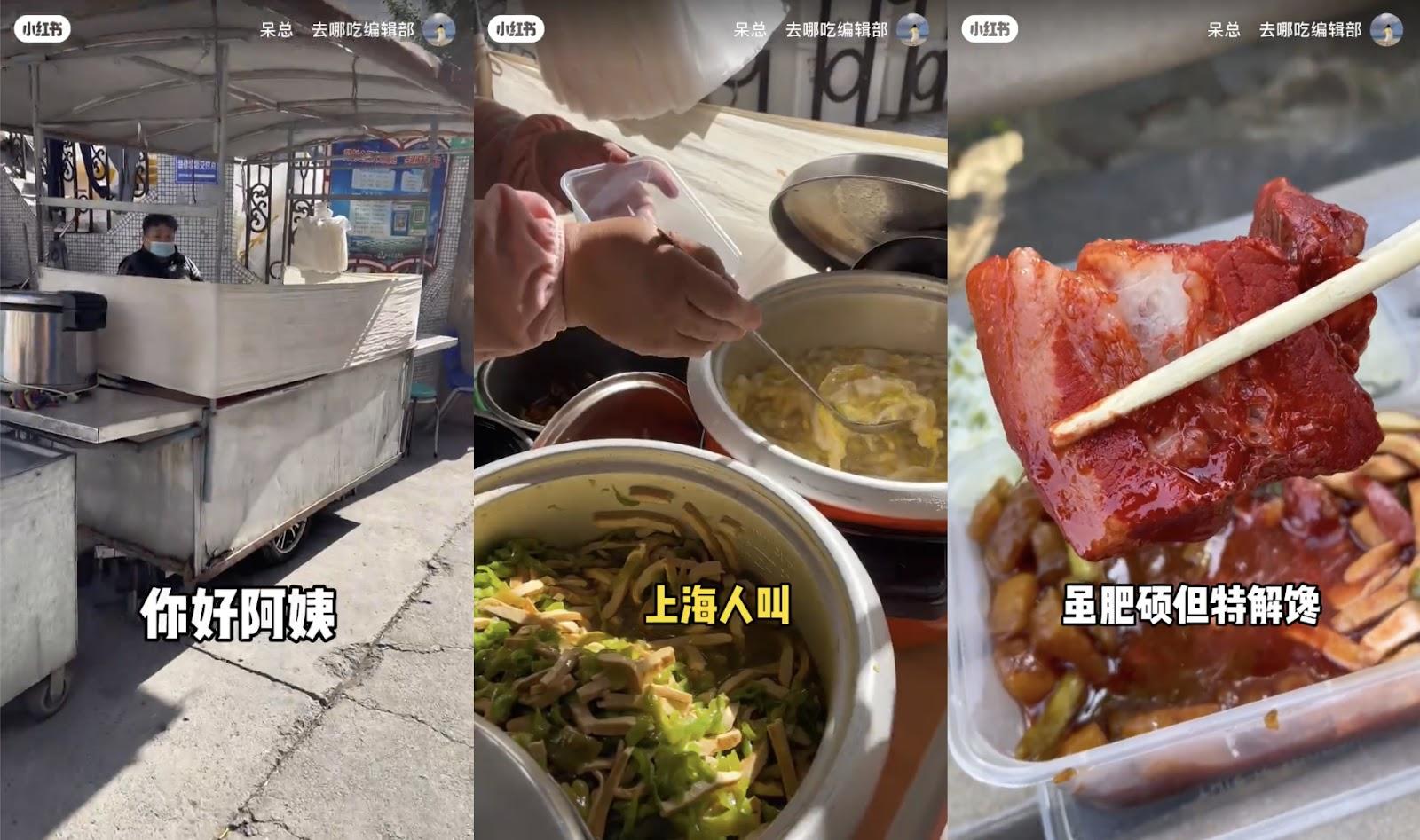

Towards the end of last year, online discussion surrounding dongbei hefan soared to new heights as food bloggers in major cities set out to find local equivalents.

On December 24, Dāi Zǒng (@呆总), a Shanghai-based food influencer with around 340,000 followers on Xiaohongshu, posted a video of herself patronizing a food vendor in the city’s Yangpu District. The stall is locally famous: It’s been in business for 16 years, and has cultivated a loyal base of customers for selling only one thing — lunch sets priced at 20 yuan ($2.98), which include two vegetable dishes and two protein offerings.

A downgrade in food consumption

There are multiple ways to explain the growing fascination with dongbei hefan, according to Arnold Ma, CEO of Dao Insights, an online publication that covers consumer trends in China. Most of the reasons are tied to the pandemic, which made Chinese people more conscious about their spending behavior and of the living conditions of essential workers — like those on construction sites — who make up the main customers of dongbei hefan.

“The sheer quantity of food available holds an optimistic message — one can take pleasure in the act of consumption and even indulge in terms of the amount of food eaten, all whilst saving money,” Ma told The China Project. “I think it shows the tentative nature of consumption culture in China right now, which is very much tied to people’s experience of lockdowns.”

Ma added that although Chinese consumers want to return to pre-pandemic life, they face the reality of a global economic downturn and the beginning of “a new more frugal era in China,” where “price-to-performance ratio (性价比 xìngjiàbǐ) takes precedence over aesthetics and class signifiers.”

After the lockdowns

In 2022, the youth unemployment rate repeatedly hit new highs, rising from 15.3% in March to a record 19.9% in July, the highest rate since Beijing started publishing the index in January 2018, when the rate was 9.6%. Confronted by an economic slump that has been going on for several years and was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, many Chinese companies — including big tech firms like Tencent and Xiaomi — cut jobs, slashed salaries, or implemented hiring freezes.

After Shanghai emerged from a brutal months-long lockdown last year, Mia Cao returned to working from the office in September. Although she wasn’t personally affected by the layoffs and pay cuts, Cao said that the constant barrage of grim economic news made her feel that it was unwise to splurge 35 yuan ($5.2) on fancy salads or take-outs. She started bringing meals from home to cut costs, and brightened up her lunch time at the office desk with “some sort of food-related entertainment,” she said, such as videos of dongbei hefan.

A slew of food and drink brands have noticed the change in people’s spending habits. Junni Zhang, a market analyst at Daxue Consulting, a Shanghai-based market research and consulting firm, pointed to HEYTEA 喜茶 as an example. Since the beginning of 2022, the Chinese boutique tea chain has launched several rounds of price adjustments, essentially capping the prices of its items at 29 yuan ($4.3). “HEYTEA’s drinks originally averaged around 25 yuan ($3.7). But as people’s income levels fell, it could not compete with affordable tea drinks in the market,” Zhang told The China Project.

Chinese high-end ice cream brand Chicecream 钟薛高, sometimes called “the Hermès of ice cream,” used to take pride in its premium image. It was the source of inspiration for the phrase “ice cream assassin,” which gained popularity in the summer of 2022 when people started using it to describe the feeling of being surprised by Chicecream’s exorbitant prices at the checkout counter — some ice cream bars cost 66 yuan ($9.85). The brand didn’t budge back then. But last week, there were reports that Chicecream is planning to launch an affordable line of cold treats sold at 3.5 yuan ($0.52).

On the other hand, budget-friendly food and beverage makers soared in popularity. In the ultra-competitive Chinese beverage chain sector, Mixue Bingcheng 蜜雪冰城, an ice cream and tea franchise known for selling $1 bubble teas and targeting cost-conscious young Chinese, outgrew its rivals and rose to the top of the game in 2022.

Buying near-expired food at discounted prices is another trend that has arisen in the wake of Chinese consumers’ changinging outlook on their finances, said Zhang. “This type of food was even among the 10 best sellers on Taobao at one point,” she said, adding that this is a prime example of how food business could remain appealing to customers by “adapting business strategies to respond to consumers’ penchant for saving.”