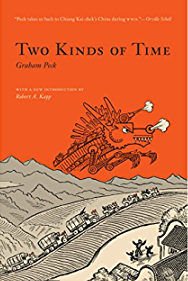

This is book No. 4 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“A book that does so much more than skim the political scum of China…rarely are ‘China Books’ written in such a humane, sympathetic vein as Peck achieves.”

—Star Tribune (Minnesota)

“Two Kinds of Time is going to do a great deal toward lifting the silken curtain obscuring the Chinese people. Peck has made the acquaintance of every type of Chinese — smugglers and pirates, children and octogenarians, conscripts and generals, farmers, spies, Nationalists and Communists. Most of them were ill and undernourished, struggling against impossible odds, armed only with a stoicism that is frequently witty and always admirable.”

—The Seminole Producer (Oklahoma)

“Mr. Peck gives a lurid picture of what we have smugly been in the habit of calling our ‘reservoir of good will’ in China. The millions of dollars which Americans have contributed has largely found its way into corrupt pockets who used it to bolster the regime.”

—The Record Journal (Connecticut)

“Graham Peck lived in caves, Chinese Inns, missionary compounds, and American barracks. No dirt, no privation, no danger ever seemed to have inconvenienced him. Peck was obviously destined to travel in China as were Doughy and Burton to travel in Arabia.”

—New York Times

“In the most vivid way, Peck takes us back to Chiang Kai-shek’s China during WWII, and by doing so, reminds us of the amazingly transformative odyssey this so-called ‘sick man of Asia’ has been on since.”

—Orville Schell, Arthur Ross Director, The Center on U.S.-China Relations, Asia Society

“This unique and fascinating book tells how Graham Peck looked into the hearts of the Chinese of his day, from peasant to coolie to clerk, and understood what he saw as few Americans ever have. Today, rising China is immersed in a new kind of revolution. Understanding China is critical for our future — this book is a unique treasure — house of background for that understanding.”

—Sidney Rittenberg, (1921-2019), long-time resident in the People’s Republic of China

About the author:

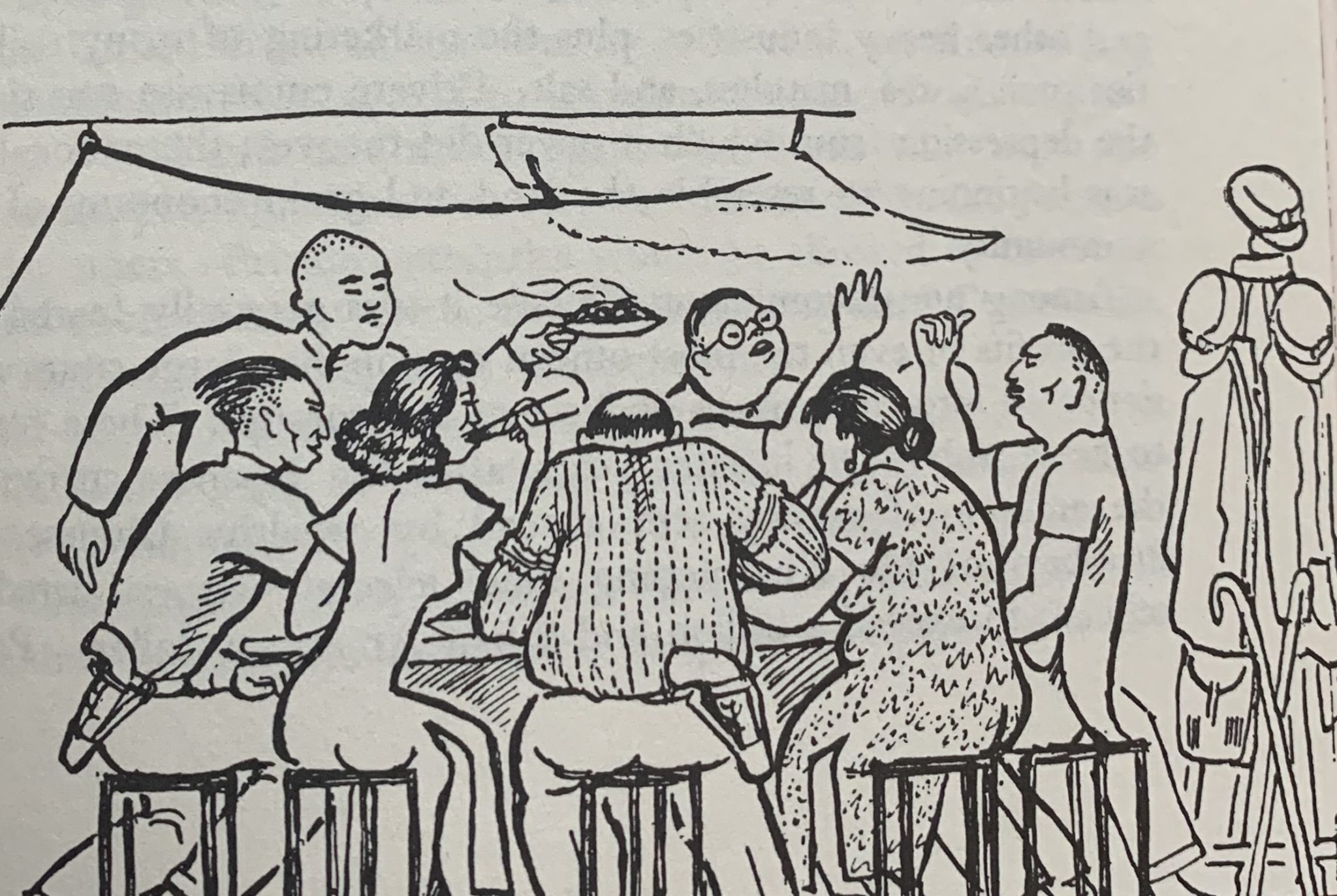

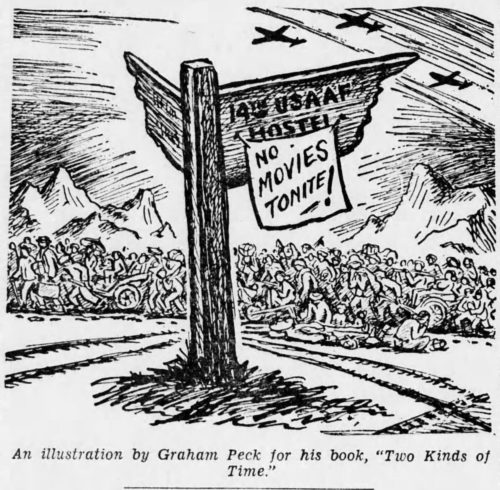

American Graham Peck (1914-1968) was from Derby, Connecticut, the son of a successful industrialist. He made his first trip to China — lasting two years — in 1935 after graduating from Andover and Yale. In 1940 he published his first book, Through China’s Wall. Time Magazine described the book as “part exquisite travel book, part exciting history, part exotic philosophy, and above all a portrait of a race that explains why the Chinese people lose battles but somehow win wars.” During World War Two he returned and worked in China with the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI), during which time he traveled extensively and gathered much of the material for Two Kinds of Time. Peck was to release several editions of the book with additional material and illustrations over the years as it remained of enduring interest to those interested in wartime China and the immediate years preceding the 1949 revolution. He also published an autobiography, The Remembered Life, in 1968, and additionally wrote several well-received children’s books.

The book in 150 words:

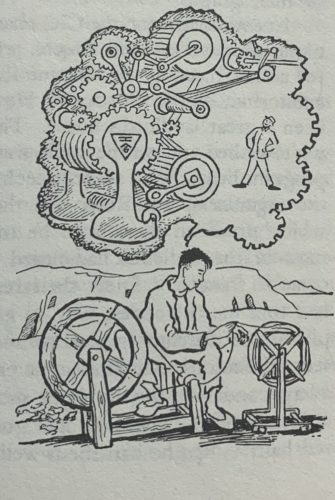

Graham Peck made his first trip to China in 1935 and from the start was collecting the minutiae and anecdotes that he eventually published as Two Kinds of Time. When he returned during World War Two, he revisited many places to see the effects of the Japanese invasion. The book is essentially a literary woven tapestry of seemingly trivial incidents Peck observed that caused Chinese society to coalesce into fertile ground for a revolution. His memoir puts into perspective how much changed in China during the Republican Era and Second Sino-Japanese War, and how much had really not changed over the last several centuries. This idea of two kinds of China was, Peck noted, most obvious in the old imperial capital Peking, soon once again to become capital, though this time of a People’s Republic. The fracture between the two times was perhaps most acute in 1950, when the book came out and just after China had been supposedly “lost” by America.

Your free takeaways:

“In a society like China’s, revolution can be a fundamental and entirely natural fact of life, as hard to slow up as a pregnancy.”

“By one Chinese view of time, the future is behind you, above you, where you cannot see it. The past is before you, below you, where you can examine it. Man’s position in time is that of a person sitting beside a river, facing always downstream as he watches the water flow past.”

“Nevertheless I think that like every other human activity, each case of communism must be judged by its own circumstances. Each national Communist Party must be evaluated against the backdrop of its own country.”

“I don’t doubt there is a great deal of wretchedness in China today, perhaps more than ever, and the Communists have no doubt caused some of it. But as the American press does not emphasize, much more of it is the Communists’ heritage from the feudal past, the Kuomintang’s period of misrule, and the years of the Japanese invasion and civil war.”

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Two Kinds of Time is a lyrical, often poetic, sumptuous read, and illustrated with the author’s own, often humorous, cartoons. Peck wanders China’s byways and backstreets over 15 years and finds an old society crumbling, indeed often one barely changed by the first Chinese Republic. But Peck, for all the delights of reading him, is a reminder to us of something we must always keep in mind and be wary of when perusing the Ultimate China Bookshelf — nostalgia. Is nostalgia a crime, a sin, an intellectual weakness, a temptation, or (whisper it)…a pleasure?

Peck is conscious of his occasional wistfulness when encountering a particularly (to him) charming, but dirt poor, village. He pulls himself up short when slipping into nostalgia for an older China — but ultimately never ignores the utter poverty so many Chinese were condemned to in the first half of the 20th century. While Peck feels wistful for an earlier, rural China — his first kind of time — he is not sympathetic to those he perceives to be simply nostalgic for the old treaty port, semi-colonial way of life. During the war, when stationed in the wartime capital Chongqing, Peck called the city a “backwater” and a “doghouse” for Americans there. He wrote that while many of them found a sort of glamor in inhabiting the most bombed city in the world, they still felt a certain nostalgia for pre-war Shanghai and its privileges.

For Peck, the widespread corruption he identifies as endemic to the Nationalist regime under Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) is not a minor problem to be dismissed, but rather the lived experience of the majority of the Chinese people — the “constant squeeze.” Peck presented an alternative to what many other “China Hands” (including Carl Crow, our first entrant on the Ultimate China Bookshelf) believed. The most prevalent attitude among American China Hands at the time was that the rampant corruption of the Nationalist leadership, up to and including the Chiangs, was a result of the chaos of the 1930s and the Japanese onslaught. The problem was a secondary concern to the defeat of Japan; after this had been achieved, the regime would settle and then follow the example of the United States and build a successful republic. As Peck’s book was published, the arguments over China in Washington, D.C., were becoming vitriolic.

There was no shortage of political polemics about “who lost China” in 1950, not least from Senator Pat McCarran in his infamous “McCarran Report” railing at China Hands, including the diplomat John Paton Davies Jr. and the Sinologist Owen Lattimore, hellbent on ruining their lives and careers. Even later, looking back on events, Noam Chomsky was to declare that “the ‘loss of China’ was the first major step in America’s decline.” But what really all the legion of analysis published in the early 1950s — steeped in Cold War fears and anxieties as it was — forgot was exactly what Graham Peck focused on in Two Kinds of Time: How were the times changing for ordinary Chinese people?

And Peck’s conclusion was that the Nationalists had become so corrupt that any preventive measures, any reforms, would now make no difference to the regime’s downward trajectory. Indeed, that this was in a way a replay of the collapse of the Qing in 1911 — too little, too late. Peck believed that China would have to “undergo the birth pangs of a revolution” (though he did not necessarily believe this had to be a Soviet-style communist revolution). If anyone in America was to blame for “losing China,” then it was those who had propped up Chiang’s regime. Peck makes the argument that the communists took China by default — not so much a Cold War victory for the USSR and Marxism-Leninism, but more a defeat for America and democracy. It’s a debate that’s rumbled on in one form or another from then right up until today. Just how much influence does America (or those pesky “foreign forces”) have in influencing events in China? In Beijing the narrative around Chiang Kai-shek since 1950 has veered from traitor to “misguided-patriot.”

1949, and the immediate interregnum as the new regime consolidated, is an era we must all come to some conclusions about to understand the subsequent 70-plus years. When we see anger at free-spending bureaucrats, Party graft, and seemingly unfair fees and taxes, we can understand both the rage and the response better if we go back and read Graham Peck.

Interestingly, Two Kinds of Time appeared on bookshop shelves at approximately the same time as another China book, Derek Bodde’s Peking Diary. Bodde, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who had spent a decade in China before the war, then spent 1949 on a Fulbright scholarship that happened to coincide with the revolution. Bodde’s book could easily qualify for a place on the Ultimate China Bookshelf were it not for the far greater breadth of anecdote and example in Peck. Additionally, Bodde managed to incite the ire of both the pro-Nationalists who were sticking by Chiang and the Communist Party USA’s newspaper, The Daily Worker, for his critiques of the communists, thus ensuring — as has been the case for many China Watchers throughout the subsequent decades — an uneasy place somewhere between the pro- and anti-China factions.

So Peck makes it onto our shelf. It’s fascinating to watch the author slowly develop from a young Yalie with a sketchpad in 1930s Beijing in his first book, Through China’s Wall, to a compassionate but increasingly exasperated observer of one of the bloodiest shifts of power in the 20th century in his second, Two Kinds of Time. Little wonder that his account of the 1940s was reissued and closely reread in Vietnam-era America.

Next time:

The first half of the 20th century saw Western bookshops (and often those of China too) full of foreign accounts of China — the country, its culture, politics, and society repeatedly explained by Americans and Europeans. Between the wars it seemed more likely that a New York publisher would translate an account of China by a Parisian or a Londoner than anyone from China. Consequently, one particularly thoughtful, literary, and erudite Chinese writer sought to introduce and explain his country to foreign readers in English. He partly succeeded, indeed became a bestseller and one of the most oft-quoted men of the 1930s.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.