This Week in China’s History: February 11, 1958

When Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, it was a revolutionary moment. Over the next decades, patterns of governance, social hierarchy, landholding, and almost every other facet of life was changed.

Down to the language.

Anyone with even a passing familiarity with the written Chinese language — really, anyone who can picture a Chinese street scene in their mind’s eye — will recognize the importance of Chinese characters. Often intimidating to learners, characters define not only the language’s writing system, but are essential aspects of design and aesthetics in China.

But they are also notoriously difficult — at the very least time-consuming — to learn. Educator and linguist David Moser has described (in a festschrift celebrating the career of legendary scholar John DeFrancis) characters as “beautiful, complex, mysterious — but ridiculous.” Besides rising to the rarified air of appearing on the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, Moser has made a career of learning and teaching the Chinese language, and among other things he points to the challenges of a (mostly) non-phonetic writing system. There is simply no way to learn Chinese characters other than memorizing them, and no other reliable way to know the meaning, or pronunciation, of a character.

Whether or not characters are an obstacle to literacy remains the subject of vigorous debate, but the terms of the debate are easily grasped. Basic literacy in Chinese requires memorizing thousands of characters, in thousands of combinations. Contrast this with the Latin alphabet, which can represent every English word by combining just 26 characters. When Mao came to power, as the head of the Communist Party and founder of the People’s Republic, one of his first priorities was an overhaul of the writing system in China: simplifying — and maybe replacing? — the characters that had been the backbone of the written language for millennia.

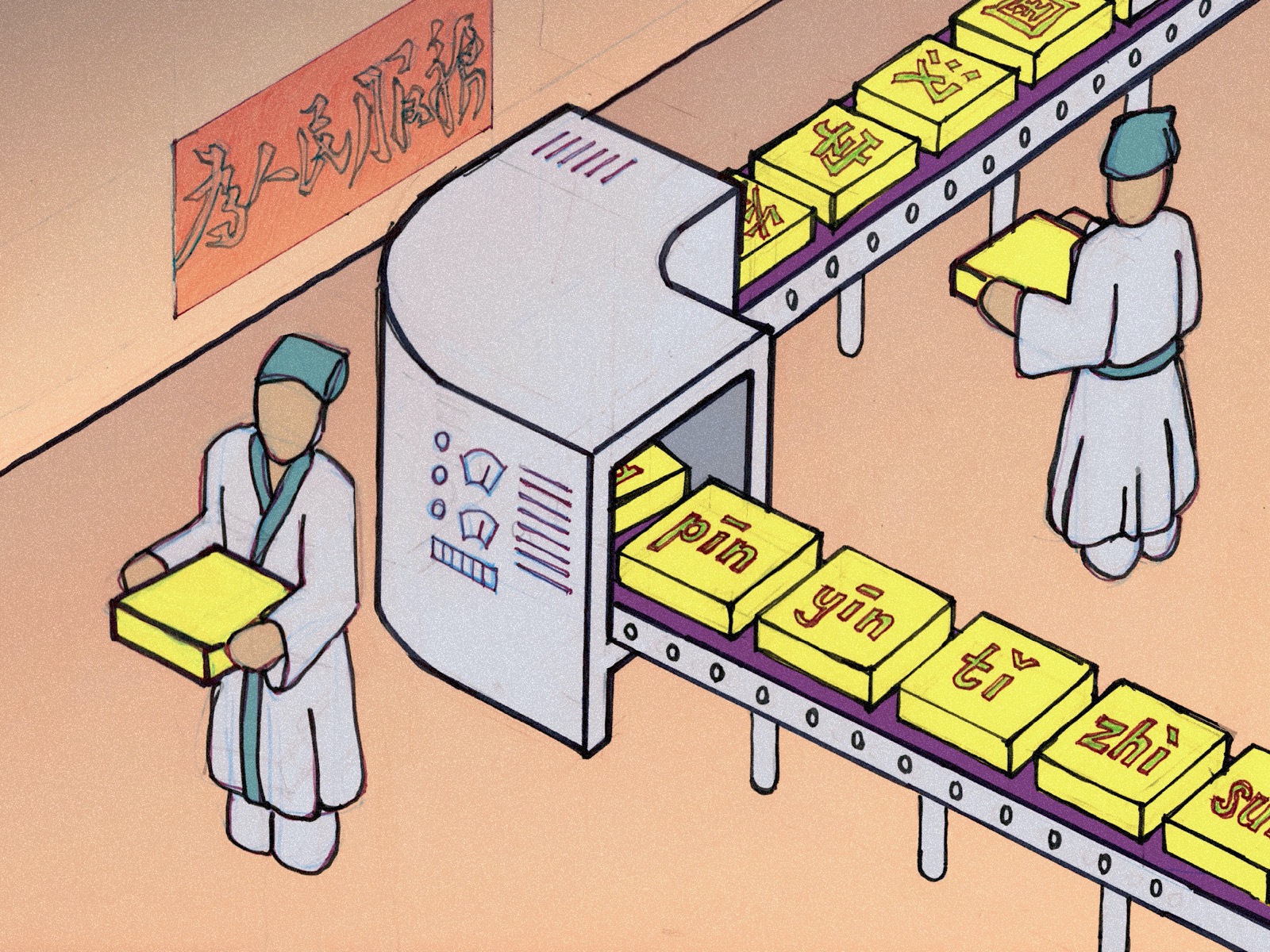

But for the Communists, centuries of history and tradition were bugs, not features. With the stated goal of increasing literacy and promoting education, on February 11, 1958, the PRC introduced a new system for rendering the Chinese language, using not characters but the Latin alphabet: Hanyu pinyin (汉语拼音 — to illustrate what we mean…hànyǔ pīnyīn).

The need for romanization — or at least for some sort of phonetic representation of the language — is easily demonstrated. Before email or easy international telephone calls, sending mail from a non-Chinese speaker required some complex workarounds (mailing labels with characters written out, for instance). A system enabling people who didn’t know Chinese to still write Chinese words is needed to facilitate all sorts of basic communication, from mail to legal documents to tickets.

Of course, pinyin was not the first system used to romanize Chinese. The Wade-Giles system, which remains commonly used, especially in Taiwan, was introduced in the 19th century. That system, devised by linguist Thomas Wade and diplomat Herbert Giles, became widespread. Then there is the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system developed by Yuen Ren Chao (赵元任 Zhào Yuánrèn), which emerged in the 1920s and was adopted as the official romanization system of the Republic of China under the Nationalist Party (KMT).

But the communists were keen on neither the treaty-port era nor the KMT republic, and looked for a new system. And they weren’t inclined to half measures. The idea of an alphabet for help with literacy or as a bridge to characters was one thing, but the communist revolution had greater goals: eliminating characters altogether (they weren’t the first; many earlier reformers had urged that characters be abolished, including author Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, who famously wrote, “If Chinese characters are not destroyed, China will perish”). Several times in the mid-1950s, Communist Party officials announced that a phonetic alphabet — the specifics of which were in the works — would “gradually” replace characters, but no timetable was ever put in place. Historian Jing Tsu writes in her book Kingdom of Characters that the members of the committee assigned to develop a new script “were certain that phonetic orthography would replace character writing in just a few years.”

But the move to eliminate characters altogether aroused fierce opposition. In the summer of 1957, the Ministry of Education formally gave up on this idea. Work toward a phonetic alphabet, however, continued.

The nature of the phonetic script was complex. The Party wanted a phonetic system that could be written simply, but also one derived from the Chinese script, rather than borrowed or adapted from a foreign writing system, like the Latin or Cyrillic alphabets. Each approach presented challenges: systems derived from Chinese scripts, like the bopomofo system developed in the early 20th century and still in use today, were more familiar to Chinese learners but had a high cost of entry to non-native speakers, defeating one purpose for the reform. Meanwhile, a system based on Latin or Cyrillic letters not only smacked of colonialism but was by definition not well-suited to the sounds of the Chinese language. And Mao’s guidance on how to proceed was mixed.

When a draft proposal for a phonetic script was rejected in 1954, two committees were formed to start nearly from scratch. Zhōu Yǒuguāng 周有光 — who died at the age of 111 in 2017 and is commonly celebrated as the creator of pinyin — was an important member of these committees. After a year’s work, according to Tsu, “no final decision had been reached after a dozen more meetings, but there was agreement that the Latin alphabet” would be the basis for the new system, to be called pinyin. A draft was put forward in February 1956, which was then revised after another year of public and expert comment.

The final version for pinyin utilized the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet (though “v” is not generally used for any Chinese words, and on many pinyin keyboards simply produces the letter ü), in the same order and using approximately the same sounds (or at least possible sounds) as in European languages. There are of course a few important exceptions, which vex any new learner, the main ones being q — representing the sound that was “Ch’” in Wade-Giles — and x, representing the sound presented as “hs.” Hyphens and apostrophes were no more, except in cases where syllable breaks were ambiguous (e.g., Xi’an, the city consisting of two characters, vs. the single character xian).

Beginning in February 1957, pinyin became the official romanization system of the PRC. Tens of millions of schoolchildren began learning Chinese with the new system. Peking became Beijing.

Although imperfect, pinyin has become the global standard for rendering Chinese, though other systems — mainly Wade-Giles — remain in use. Pinyin was adopted officially by the United Nations in 1986 and is used by most international news organizations.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.