Three Chinese share their stories about being trans outside China

Three non-cis Chinese speak about their experiences of coming out while living abroad, and life as a trans person in the U.S. and China.

While trans visibility has risen within China in the recent past, there are many who remain uncomfortable discussing trans rights, and — in keeping with the country’s attitude toward others in the LGBTQ community — mainstream media wholly ignores the existence of trans people. For many, it takes moving outside of China to understand their identity.

In this piece, I’ve asked three Chinese trans people who all currently live outside China — Zhi, Sophie Hu, and Kennie Zhou — to share their stories: their experience coming out, their homesickness, and their hope for a more trans-inclusive environment, both inside and outside their homeland.

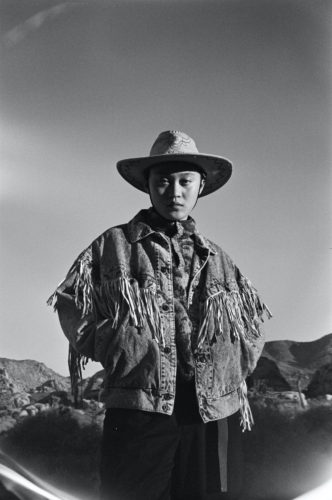

Zhi

I refuse to let my queerness and my transness disconnect me from where I come from. I love the land that made me who I am.

Can you introduce yourself? What do you do? How do you identify on the gender spectrum?

My name is Zhi, or Z if an English-first language speaker can’t pronounce my name. I’m 25 years old and I’m an artist here in New York. I have a tattoo practice. On the side I collaborate with friends on short films or other sculptural and performance projects. I’m a transmasc person. I use they/them or he/him pronouns. I also identify as gender nonconforming or nonbinary.

Can you tell us a bit about your coming out experience?

It has always been a long process and I will probably continue to come into my transness from this point on — I don’t think of transitioning as this linear or definite thing, like a point to arrive at.

When I was a little kid, I never felt I was in the right body. Or I would have crushes on boys in my school but also wanted to be them. There wasn’t language to describe such phenomena, not until I came to the U.S., where I was very blessed and privileged to have parents that supported me to higher education. There I got to meet more people that looked like me or dressed like me and fell in love in ways that were under the definition of queerness. I started becoming friends with trans people who have been on hormones and had their surgery, and seeing them really blossom and thrive in their body, and then realizing, “Oh my god, I want to be that. I’m so jealous! I’m envious of that way of living.”

I started becoming more involved with the trans community — my partner at the time, who was also a nonbinary person, took me to my first hormone appointment and paid for my first months of testosterone. I remember the first time when I was on a second date with that partner and they asked me, “What pronouns do you use?” I never thought to ask myself that question. I was aware of the correct pronoun to address people but I never thought to ask myself that and I never had someone who was physically intimate and romantically involved with me ask me that question. They see something in me that I didn’t even see myself. I was like, “Maybe I am that trans person that you saw through your eyes.”

I was really loved and supported by people around me that showed me it was possible to be something that was given to me at birth. Without those people, I would have never known. I would probably be miserable and confused.

Did you come out to your family? How did they react at first? How are they coping with this now?

So I first came out to my mom [who lives in China] when I was 18, but at the time as a cisgendered queer person. She took it really hard. She felt like it was the art school that corrupted me or because I was away from home. It was really hard. And then we stopped talking for a while but then she kind of came around, realizing that if she let this get between us then she would lose me in her life. And then we started talking again as parent and child.

Then, actually not too long ago, I officially came out to her as a trans person — not only like what my pronouns are, what it means to be trans, what it means to be gender nonconforming, why my voice is deeper…I talked to her about my top surgery. The first time I came out I was 18, and I’m 25 now. So it’s been seven years and it’s been long enough for her to catch up with the vocabulary and be more accepting and open. This time around she was like, “I’m glad that you are being yourself.” And she was asking all these curious questions like, “What are hormones like?” “What is top surgery like?” “What does that mean that your chest is flat?” and she asks these questions in a genuine, curious, and caring way.

I don’t have a big family, and I’m the only child in my family. I am the closest to my mother. She is a really important figure in my growing up. For me, coming out to my mother wasn’t from a place of, oh that’s my responsibility or I have to do it or this is like my duty as a child. Not at all. I told her when I was ready to tell her. I told her because I want to tell her. I love her very much and that’s a family that I want to involve in my life. I want to grow old with her.

Did you have your gender legally changed to align with your identity here in the U.S.? If so, tell us what the experience is like for you.

I’m in the process of applying for permanent residency, and so, yes, my lawyer has petitions for me to change my gender marker because I’ve gone through top surgery. And my surgeon, actually after the surgery, wrote me a letter as an official document to prove to the state that, “You’ve undergone this gender confirmation procedure that qualifies you to be a trans person and that you wanted this gender marker to be on a document.” Which I think is a little bit silly — we have to have a doctor to prove to this day that we are something that we are. But I’m also really grateful that the surgeon had foresight and wrote me that letter that I could just use in my process of applying for permanent residency and use that as supporting evidence.

Have you been back to China since your transition?

After I started medical transitioning, after my voice started to change, after I grew a very small amount of baby facial hair, I haven’t been back. To be frank, I still don’t feel safe, even though I have a mother who supports me, but that’s only one person. I grew up in a really small city; I didn’t grow up in a major metropolitan area. So that means that people haven’t seen trans people around; or maybe there are trans people around, they’re just invisible to us — cause there have always been trans people.

What do you miss most about China as a Chinese trans person living in the diaspora?

I think there is this kind of sadness of almost losing my homeland. Like, I know that my homeland did not disown me, but in a way, I feel like my transess was pitted against my national identity or my cultural identity — that I could either be trans and be safe here, or go back and mask a part of my true self. I think [this belief] might be specific to the fact that I grew up in a really small city where queer culture isn’t very visible.

So I like to half-jokingly describe my tattoo practice as “a queer and trans diasporic tattoo therapy.” Of course, I’m not a licensed therapist and that’s why I say it half-jokingly, but because my clients are usually queer and trans Asian or different black and indigenous people of color, and they bring me their migration story, their family story, and how they come into their body. And I use tattoos as a storytelling way to regain agency for their own body. The pieces that we put on to adorn ourselves are new armor. I think my tattoos and the work I do are these gifts that allow them to see themselves in a more beautiful and present way.

I also think that my tattoo practice is my own manifestation of homesickness. I haven’t been back for so long. But when I think about Chinese folktales, when I make work that connects with the stories I would hear from my aunts or my grandma about these ghosts and mythical creatures, it makes me connect to my ancestral memory. I refuse to let my queerness and my transness disconnect me from where I come from. I love the land that made me who I am, and that’s my way of staying connected with them. There’s so much to say about folktales and mythical creatures and even deities — our deities are, if you really think of them, so gender nonconforming. They’re so queer and there’s so much transness in those stories. So I kind of make it my mission to “queer” these stories and bring them to life for people who need it.

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in China?

I’m not quite aware, to be honest. But I think to have such a rigid system, like, “You have to go through hormone therapy and then five years later you can qualify for this kind of surgery and then you have to have all these surgeries in order to be qualified as a trans person,” I think it’s not only binary, but also just incredibly pathologizing, to decide who qualifies as a valid trans body, a safe trans body in the world.

What do you think China is doing better in terms of trans care?

I know a lot of my friends here are international students who grew up in China in major cities, and they would tell me all these wonderful things about queer nightlife and meeting other gender nonconforming people and that there is an underground, if not thriving culture that supports trans people or gender nonconforming people. I love hearing those stories and I am hopeful.

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in the U.S.?

A lot of my friends are trans. My previous partner is a transfem person, and I would be intimately witnessing from small micro-aggressions that she faces on the street to stalking to slurs being thrown at her and actual violence in physical intimacy done by strangers. I know trans women that passed away. We hold vigils for them. You know, people are disappearing, especially black and brown trans women. The ones who are at more risk are where they have more intersectionized marginalized identities. I’ll witness my partner at the time who was a beautiful transfem person constantly feel like they’re not passing enough [as a cisgender woman], or this stranger might spot something, or their voice is too deep, or they carry their body in a way that might reveal them to be a target of hate crime. We walk around on the street constantly vigilant or alert of what might happen to us. You just never know. What that does to a person’s mental health and in the long run is unthinkable.

Sophie Hu

I have not been back to China, so I don’t know what it will be like. I’m low-key excited and low-key very afraid.

Can you introduce yourself? What do you do? How do you identify on the gender spectrum?

I’m Sophie. I identify as a trans woman. I use she/her pronouns, and I’m a filmmaker who wants to focus on making high-concept queer sci-fi fantasies. And I like to invent random food concepts. My recent invention is this hunger-quenching drink that utilizes placebos to make people forget about their hunger, thereby not getting hungry when they’re waiting in lines in front of a very popular restaurant. So, that’s what I like to do for fun.

Can you tell us a bit about your coming out experience?

Yeah, I first realized there’s something “weird” about myself when I was in kindergarten watching this Japanese show called Ultraman. I always loved the kind of rubber smoothness of their body. Obviously it’s about a man who transformed into this giant creature with no genitals down there. I always found myself “wrong” to watch it and told my parents I was afraid of it and never watched it (much). In middle school, I had more control over the internet and I started to look for pornographic videos, and a big part of the realization was that, for one thing, I was really ashamed to watch porns online because that’s more like a taboo. And what’s worse was that I was very — and still am — very into porns where “violence” was conducted against women, and what made me feel further humiliated was that I identified with the woman in the porn because I found it thrilling to imagine myself being dominated, whether by a man or a woman.

So this continued until when I was in college in New York. I was telling my friends that I felt like my life would be better off if I was a woman, and my friends were like, “Maybe you’re transgender.” I didn’t have the desire to have surgery or to take hormones, and they were like, “Transgender people don’t have to have those in order to be trans.”

So I came out to three of my friends back in 2016, and they’re all very supportive. A friend of mine helped me take some pictures because I was only doing self-portraits and this one photoshoot really changed me. She was doing my makeup and hair. I was just like,”Well, there’s no way for me to pass. There’s no future for me.” They thought I was pretty. I don’t believe them. I don’t think there’s any great representation of Asian trans women or trans men on any mainstream media. There is no viable path for me to live like that. My main fear was that people would be like, “No no, no, that’s not a trans woman.”

It took me really until 2020, when I was in lockdown living by myself, I realized that it was just so awful to live for the fear of how other people would perceive me.

Did you come out to your family? How did they react at first? How are they coping with this now?

I came out to my family in December of 2020. It was because my parents were going through a divorce and they were like,”You don’t understand my life. You don’t understand what we’re going through.” And I was like, “You don’t understand what I am going through.” I was just gonna let it out — things can’t get much worse than that in this argument. I felt like for my whole life, I was hiding something from everyone and it was absolutely psychologically stressful.

None of them said, “I don’t accept you.” At first, they were unprepared and they were nice. Eventually, my dad stopped liking to talk about it. My mom — for a year when I was correcting her (about my gender) — she always thought I was overly sensitive. The reason I had to be more ballistic about it was that I wanted them to take me seriously. I wanted them to not think that I was experimenting. I wanted them to think it’s a decision I’ve been trying to make for a long time and finally I’m able to make the decision that’s more right for my life. So I was really arguing with them about how to call me and certain views. And my mom really came around and she’s really supportive. I think her friend group has been more on the liberal side, so her friend group has been supportive of me, so it’s pretty public at this point amongst my family’s friend group. I’m grateful to have the family I do.

Did you have your gender legally changed to align with your identity here in the U.S.? If so, tell us what the experience is like for you.

Yeah, I did that for my driver’s license. It was unbelievably easy and that was really helpful.

Have you been back to China since your transition?

I have not been back to China, so I don’t know what it will be like. I’m low-key excited and low-key very afraid. I always live a really provocative life, and I definitely don’t mind people staring at me, like trans visibility — “Stop your traditional way of thinking.” Plus, so many people love Korean pop stars — these fem boys anyways — so why can’t you just be more inclusive, with gender expressions? For the political part, I’ve been in the United States for 12 years and I’ve been working in the arts. I just don’t want to be spied on. I definitely see that as a possible danger. I’m afraid it’ll be seen as, “Oh American brainwashing has brainwashed her so much that she thinks she’s no longer a man.” But I’m curious to see whether people will be outright laughing or if we’re just kind of assuming that everyone’s hostile. I’m curious to learn and I do hope for the possibilities of change.

What do you miss most about China as a Chinese trans person living in the diaspora?

I miss the beautiful nature and some of the things I could do, mostly food-related. I’m sorry I don’t have any friends in China. I lived there for 14 years with not a lot of good memories. Elementary school was good. Kindergarten was a blur. Middle school was absolutely awful. And after that I left. So not a lot of good memories with friends. I don’t know what it’s like to socialize as an adult in China. Part of it is social etiquette. I like to be honest and I don’t like to engage in formalities.

But over the years I definitely see positive things. I learned from my parents, from certain strands of Chinese culture. There are things I learned when I was growing up in China that I value. So there is definitely a level of greatness. I feel I’m indebted to things that are passed down to me from friends and family.

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in China?

There’s no representation, therefore it’s hard for people to see different possible lives people can live. I think that’s the biggest challenge.

What do you think China is doing better in terms of trans care?

From my limited knowledge, I don’t know. I’m acquainted with some trans women in my city in China. The medical treatment or medical care for trans people, like the hormone they need, can be very difficult to get, and things cannot be done in a very public manner. It feels like people don’t understand what we are, so the first legwork is actually to try to tell them what gender identities and sexualities are.

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in the U.S.?

There are so many issues trans people are facing, but the main question is about right-wing people — how can we stop them from spreading all this anti-trans rhetoric? It’s not even about the facts anymore at this point. Even if it’s some issue that does not have to do with trans people, (the right-wing) says, “Okay, yeah, these are just liberals going crazy, therefore they should not be allowed in public restrooms, or therefore they should not have the care they need.” It’s not even about the issue itself. It’s just about us versus them.

Kennie Zhou

It was really exciting to see that I could do something as myself and to help other people with their issues and their identities.

Can you introduce yourself? What do you do? How do you identify on the gender spectrum?

My name is Kennie and I am a nonbinary person and very fluid; my identity changes a lot over time. And my presentation has also changed a lot over the years. When I first came out as nonbinary, I was much more masculine, and now I go back and forth on the gender spectrum. I use all pronouns — I just say “they/them,” because if I say “all pronouns,” people are just going to assume that I’m cisgendered. It’s like you can’t give people options to call you by your assigned gender at birth, so I usually just do “they/them.”

I am mainly a producer of short films and music videos and I also direct and do performances. I watch a lot of shows and anime. I feel like somehow a lot of trans and nonbinary people love anime because it’s very gender euphoric — there’re a lot of characters, I’m like, “Okay, I see myself in this person.”

Can you tell us a bit about your coming out experience?

I guess there was a time when I was in middle school, I didn’t understand or have any idea of what’s “normal” for sexuality. So I was dating a girl, and it was just like a child’s play type of situation — where we’re dating but it’s kind of funny and not that serious. And I didn’t realize that was some “homo” behavior. I didn’t have any terms for that at all. Then in high school, the funny thing is that she broke up with me and then she found me a boyfriend. [Laughs.] I think that made me feel a little bit strange about myself for the next couple of years, and I was trying to date straight men but I was failing, like I just couldn’t do it? So I was not dating anybody for a really long time.

And then when I came to college in the U.S., there started to be more education on LGBTQ identities, and there was this “Come Out Wall” thing for Pride Month, where we were asked to either be an ally or be the coming out ones on the wall. (That was a little bit weird looking back, like why do you force people to make a choice?) But I was like, “Oh wait, actually I’m not going to put myself as an ally; I’m going to put myself on the list of people who are actually coming out through this.” And that was the first time really when I was confirming in written words that I belong to a community that is not heterosexual. At that time I still wasn’t sure how to describe myself. I was just like, “Okay I’m queer but I don’t know. I’m still figuring it out — I feel like I’m always figuring it out.”

After that, there’re those demographic forms you have to fill in for school. And there was one where I was asked about my gender identity. I clearly remembered that I was looking at all of the options and there was one that was “gender nonconforming.” I was really happy and I was like, “Oh yeah, that’s me.” So I marked that on the paper, and I think I confirmed in written language to myself that I’m not a cisgender person. I guess after that it just became more and more ingrown with myself and it slowly blossomed from there.

Did you come out to your family? How did they react at first? How are they coping with this now?

I guess indirectly, because I used to do drag in China after I graduated from college. I was posting a lot of gender-related content on my WeChat. I would sometimes just send that to my family group chat as well, and then they would just see it and not respond to it? But my mom sometimes likes my posts where I’m actively speaking about my experience or posting photos of me being clearly not heterosexual. So it hasn’t been a conversation, and I’m curious to see what happens.

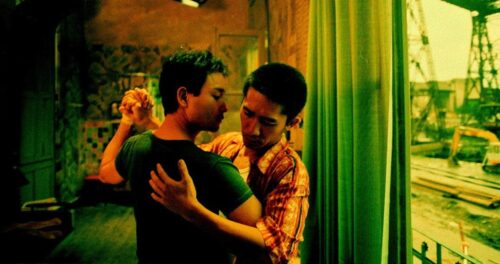

That’s so cool that you did drag in China, can you talk a little bit about that experience?

Yeah, because I graduated during COVID in 2020 and China was doing really well… a lot of local artists were able to thrive during that time. I was talking to my friends who do this party called “http” — “H” in traditional lesbian language means “the middle”; “T” like tomboy, the masc lesbian; and “T” is also for trans; and “P” means the fem. [Editor’s note: Lesbians in Taiwan used to refer to feminine types as “Po (lady),” which later became P, though the letter may also stand for “pretty girl.”] So it’s a party for non-cis gays, basically. I started with them and I feel like at that time there were mostly only cis gay men who do drag, and we need somebody else who’s not a gay man to do drag. I always wanted to do drag so I started the project then. It was nonbinary drag.

Did you have your gender legally changed to align with your identity here in the U.S.? If so, tell us what the experience is like for you.

Not yet, I’m a little unsure because I have two different identities in China and here. I think I want to change my gender into an x. And I want to change my name too. But I don’t know how that’s going to link back to my passport in China, and, yeah, I haven’t figured it out yet. It’s probably easier if I’m only choosing to live in the U.S. I’m just worried that in my career, I’ll have potential problems when I’m going from here to China or from China to here, and that my paperwork doesn’t match. So it’s very much a bureaucracy thing that’s stopping me.

Since being nonbinary is still a very new concept for Chinese people — I think maybe even more so than being trans — have you been back to China as a nonbinary person? What was that like?

Yeah, I have. I do find it very difficult to make people change how they refer to me. Even a lot of my friends who know that I’m nonbinary still refer to me as “she/her” [in written Chinese, since pronouns all sound the same in spoken Chinese], and I have to take a lot time to be like, “Hey, I do use all pronouns but if you only refer to me as ‘she/her,’ that’s misgendering me.” I think in their brains, I’m just like a gay “girl” or an androgynous presenting “woman” instead of a nonbinary person.

It’s interesting because there are a lot of really masculine women in China, but a lot of them still identify as women. But they’re like tomboys (铁T) — they’re more masculine than me and they tend to use their assigned gender as their pronouns, and I think that confuses a lot of people. They’re like, “Oh you’re not that masculine. Why are you using other pronouns?”

Yeah, it took a lot of work whenever I was in China to either bear the burden of being misgendered or having to explain to them constantly.

What do you miss most about China as a Chinese trans person living in the diaspora?

I felt like it was very exciting to see how us being openly trans and openly queer could help other people understand more about this topic — there were just less education around gender and sexualities in general in China, so I felt like I was able to do something for other people who might also identify as gender nonconforming or queer, by performing, for example, or by simply being out and about. It was really exciting to see that I could do something as myself and to help other people with their issues and their identities. I feel like it’s less so here. I remember that I was performing once and I had this really phallic dildo thing in the performance and then those men who came to the show were just shocked. I’m like, “OK, I’m opening their eyes to the new world.”

You’re so noble when it comes to what you miss in China. Lots of folks just say they miss the food the most.

But I do miss food too, for sure, and I miss Taobao a lot. It’s really cheap and easy to buy stuff that can fulfill my fantasies. [Laughs.]

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in China?

I think the biggest one is that there are very few discussions about being trans in China. It’s so censored, and then without this discussion, people can never know more about this topic or about themselves. And without that sort of understanding, it’s more dangerous for trans people who are out to be themselves.

What do you think China is doing better in terms of trans care?

I’m wondering if it’s easier to get gender-related surgeries in China or not. Because I heard from this plastic surgeon that the most commonly done surgery is for AFAB (assigned female at birth) transitioning to male, basically.

Wow, that’s interesting. But I wonder how many trans people are choosing to have body surgeries because they don’t want to live with a gender marker that’s not their identity because their gender system is so rigid — you can only have a gender marker changed when you have bottom surgery.

That’s true. It’s very binary of them to do so many of those surgeries. Maybe it’s in service of changing your gender on your paperwork instead of in service of the actual person.

What do you think are the challenges trans people face in the U.S.?

There have been a lot of anti-trans regulations that have passed very recently, like literally this year, which is a really scary trend. I feel like there has been a tendency in these gender politics going back since late last year, and it’s not stopping. So I’m a little scared about how far the politics will go against trans folks. And I feel like there was a period of time when gender politics was getting more liberal or inclusive, but somehow it’s going back. That’s really concerning.