This is book No. 8 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“In a narrative that makes mincemeat of any preconception that diplomatic manoeuvrings in a far land a century ago would be as boring as last week’s front-page, Maurice Collis gives a complete account of Britain’s Opium War with China.”

—Kansas City Star

“This is a wholly admirable book, admirable as a work of history and admirable as a literary entertainment, in fact the best book of a most admirable writer.”

—The Guardian (London)

“Foreign Mud is a self-contained narrative, lucid, balanced and creating a unity of impression. Mr. Collis knows better than any man how to lick a book into shape.”

—The Daily Telegraph (London)

“An almost forgotten footnote to history, the very awkward international incident of the Anglo-Chinese war provoked by the British opium trade, given a very compelling recapitulation.”

—Kirkus

About the author:

Dublin-born son of an Irish solicitor, Maurice Collis (1889–1973) attended Oxford and then joined the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in 1911. He was subsequently posted to Burma in 1912. He moved constantly around the country, though was criticized by his superiors for being supposedly too “pro-Burmese” while working as a magistrate in Rangoon/Yangon and elsewhere — a period he chronicled in his book Trials in Burma (1937). He was demoted from magistrate to the post of Excise Commissioner before leaving the ICS.

After returning to England in 1934, he became a full-time and prolific author, writing many books, including perhaps his three best known titles on Burma — She Was a Queen (a popular novelized account of Queen Pwa Saw of the Pagan Dynasty), The Great Within (an at-the-time widely read essay on the interactions of China and Europe from the 17th century), and Siamese White (about Samuel White and the Anglo-Siamese War of 1687) — as well as Foreign Mud. Later in life he took up painting and became proficient in oils.

The book in 150 words:

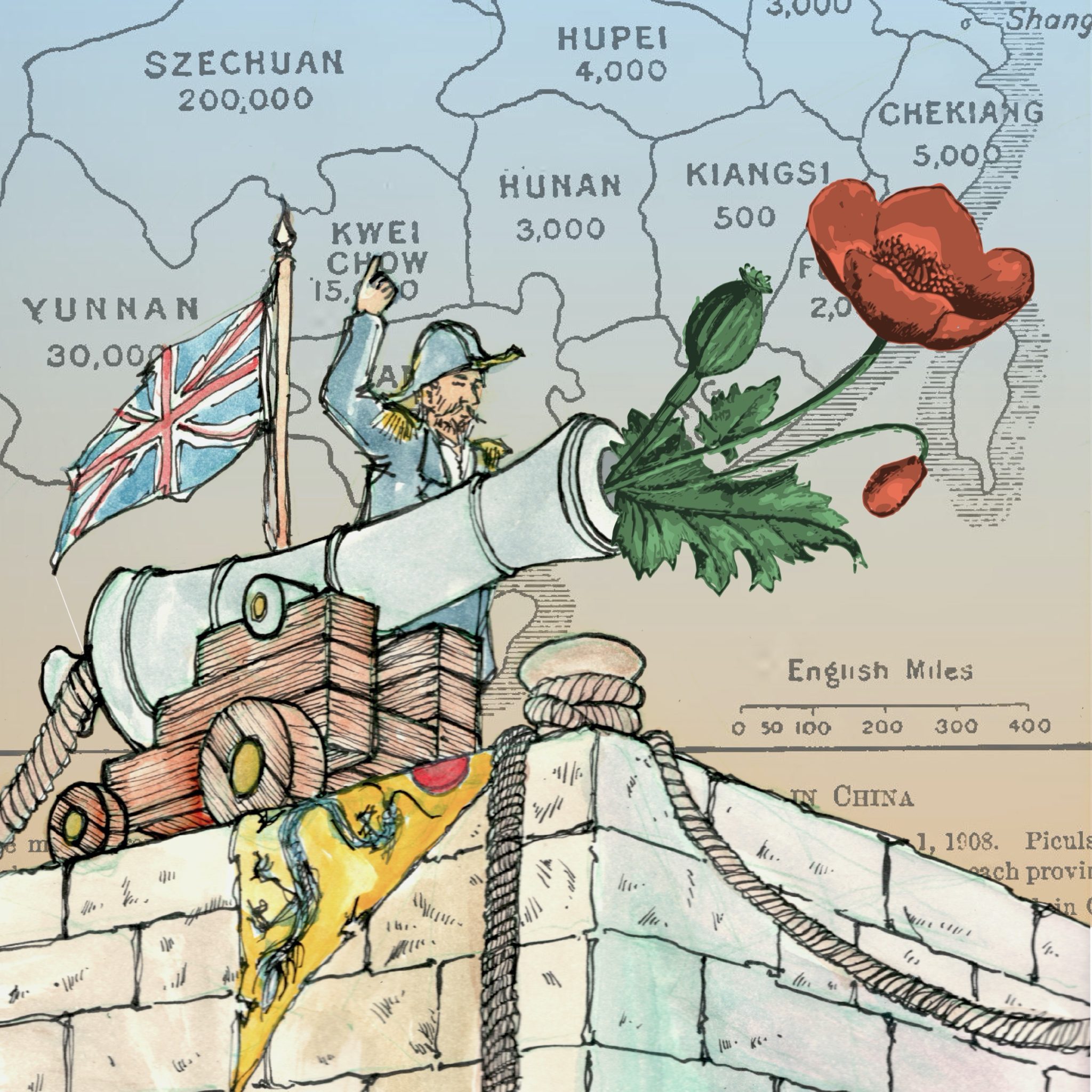

Foreign Mud is essentially a historical recreation of the events (or “imbroglio,” as the British press often referred to it) surrounding the illegal trade of opium in Canton (present-day Guangzhou) during the 1830s and the Opium Wars between Britain and China that followed. It is the story of the British drug traffic; of the very profitable commerce engaged in by the East India Company. But Foreign Mud is also about the official disavowal of the trade amid a simultaneous unofficial acknowledgment of it. Laissez-faire capitalism met with ethical dilemmas in southern China. Collis, as a former magistrate, examines the trade and the slide into war — twice — through “the presentation of evidence as in a court of law.”

Your free takeaways:

The drug traffic in China, especially when it had swelled till its value equalled that of legitimate imports, was itself a blatant disreputability, of which the East India Company was ashamed, wryly declaring it a pis aller (a course of action followed as a last resort), about which the less said the better.

It was this very drug traffic, inextricably bound up as it was with finance and British business firms, which provided the casus belli.

Next morning, 22 March, Howqua and his colleagues went to Commissioner Lin with the offer of the 1037 chests. Their reception was bad. “This is merely a fraction of the opium,” he said angrily, and refused to accept it. “There are tens of thousands of chests and I have demanded them all. Do you think my words are only air?”

What exactly Lin had finally decided to do at Macao is uncertain, whether to seize an English sailor or drive the British out of the place, or, on the contrary, detain them there until they abandon further smuggling.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Kirkus may have thought the Anglo-Chinese War, or First Opium War, of the 1830s “an almost forgotten footnote to history,” but the Opium Wars of course remain central to the narrative of Chinese contemporary history and the era of “Unequal Treaties.” Collis comes at the history of the period from a legalist position — he argues both prosecution and defense, and it is useful to an overall understanding of the period to appreciate both positions. Collis, given his previous career in the Indian Civil Service (which covered Burma at the time), is always conscious of the link between the opium trade to China and the fortunes of the British in India.

And so, an understanding of the pro-opium argument, which while of course is dismissed today, is crucial to an overall understanding of the 19th-century position of the East India Company (EIC) and the British Parliament. The “trade” would not be necessary, argued the advocates of laissez faire and opium sales/smuggling, were the Chinese not to simply open their ports and hinterlands to European trade and goods. That this did not happen justified the “trade” in foreign mud. Against this, of course, is the fact that the deleterious effects of the drug were known, and EIC often ashamed of its actions. The EIC then called on the British state in the form of Parliament and the Royal Navy, which established a harsh “gunboat diplomacy,” the memory and notion of which resonates today in rows over dumping, tariffs, and occasionally moves toward military tension over various issues.

We should also not forget — and Collis does not — that though the Opium Wars are seen as Anglo-Chinese Wars, other nations, including the United States, ultimately gained treaty port and other rights through the Unequal Treaties (notably the Opium Wars-related Treaty of Nanjing and the Bogue with Great Britain, the Wangxia Treaty with the U.S., and the Treaty of Whampoa with France). As our old friend from book No. 1 on the Ultimate Shelf, Carl Crow, once wrote, America’s treaty port rights in China were won on the coattails of England.

There is, of course, an element of the opium debate in every trade dispute that has arisen between China and the outside world ever since. Protectionism vs. free markets, from steel dumping to the infamous 2005 Bra Wars (which fortunately did not ultimately require resolution by gunboat), through to semiconductor chips and solar panels more recently. To understand China’s “outrage” and subsequent negotiating stances in trade disputes, we all need to understand the original — and nastiest — trade dispute of them all: the Opium Wars. Maurice Collis’s Foreign Mud is arguably the best overview of the conflicts.

Next time:

Next time, we need to consider a very important and influential novel by a Chinese novelist that overtly determined to show the truth of semi-colonial treaty-port capitalist Shanghai’s industrial labor, society, and exploitation in all its violent reality.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.