China’s new National Data Bureau: what it is and what it is not

China will establish a National Data Bureau to centrally manage data resources across the country and a Central Commission on Technology to speed up indigenous innovation efforts. Here's what you need to know about these two new organizations.

China’s annual National People’s Congress (NPC), which ended last Monday, carried extra significance this year in that it confirmed a reshuffling of key government posts while marking the beginning of the next five-year cycle. At each of these five-year occasions since the 1980s, China has announced a slew of institutional reforms to better align the country’s bureaucratic setup with its long-term strategic goals. This year was no exception.

The State Council institutional reforms recently rubber-stamped at the NPC were meant to advance President Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 core objectives: financial stability and technological innovation. In the area of technology, China will establish a National Data Bureau to centrally manage data resources across the country and a Central Commission on Technology to speed up indigenous innovation efforts.

The fact that the new data bureau is housed under the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) suggests a higher-than-expected risk appetite for policy innovation. The new data bureau will take over digital economy policy planning functions from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), and combine with data-related policy planning functions under the NDRC’s high-tech department. The new data bureau will supervise economic development policies broadly pertaining to data: digitizing public services, implementing the national big data strategy, establishing data factor basic frameworks, and promoting digital infrastructure.

Each round of institutional reform is an attempt to respond to a governance challenge. Prior to the reform, 18 local data authorities were being established to manage local data resources, particularly public data held by local governments and public institutions. It is only natural to have a national entity to coordinate disjointed local data policies. The National Data Bureau is not expected to disrupt ongoing efforts to shore up data security and privacy in China.

Development versus security

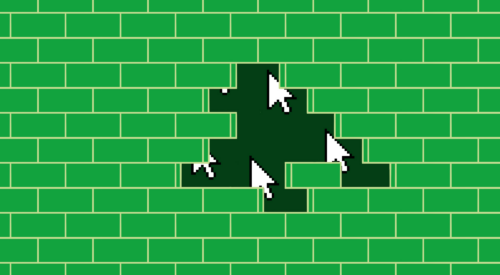

The proposed reform represents an attempt to disentangle economic and security aspects of data governance, so that the dualistic goals of development and security are no longer contained under one roof. In the past five years, China has prioritized building out and operationalizing a comprehensive legal framework for data security and privacy, sometimes to the detriment of economic vitality. For example, since the Data Security Law took effect in 2021, Chinese suppliers of metals used in electronics have been reluctant to share information with foreign customers, which makes it difficult to plan production and stay compliant with environmental rules.

Another byproduct of prioritizing security is an increasingly powerful Cyberspace Administration of China, the supra-ministerial tech regulator. The CAC is in essence a party organ, but it also carries out state functions. The CAC’s authority has reached beyond its core expertise in online content and cybersecurity to encompass digital development, such as through promoting rural digitization. By stripping the CAC of a chunk of non-security-related authority, the reform pushes back on the CAC’s ever-expanding policy scope. Arguably, the NDRC has no shortage of talent and institutional knowledge of policy innovation, and thus will be a better home for the functions that are moved away from the CAC, the powerhouse of internet censorship.

Data circulation

China views its vast trove of data as a strategic advantage. A key pillar of China’s high-level design of its digital economy seeks to promote nationwide data circulation — the idea of aggregating and commodifying data to enable individuals and firms to access the data they want. In practice, this means breaking data silos in the public sector, forming national databases in key industries, and establishing a market for transacting data assets. The thinking goes that data will be more valuable if combined with other data and made available to those who benefit from it.

Having a national bureau dedicated to data serves to coordinate piecemeal policies across the country and avoid duplicative efforts. Local governments, if acting unilaterally, sometimes engage in wasteful competition. This is evident in the dozens of data exchanges that mushroomed after China declared data as the fifth production factor, joining land, labor, capital, and technology. Rather than running fewer data exchanges at greater scale, local governments opted to build their own.

The National Data Bureau has a unique role to play in laying out foundational factors of data circulation, including a legal framework of data ownership and national standards for evaluating data assets. Paving these building blocks goes beyond the power of local governments, but local governments need them to do their part to implement top-level policy designs. How China will achieve data circulation remains up for debate, but the new data bureau shows China’s determination to get the ball rolling.

Maintaining the status quo on data security regulation

The current reform would be far more sweeping if China were to centralize data security regulatory functions to a national bureau similar to the State Administration for Market Regulation, which handles market regulation and antitrust issues. In that case, the hypothetical data regulator would resemble a national data protection authority. However, Xi opted to keep the current structure intact. The CAC still takes the helm, leading the cybersecurity review and the cross-border data transfer workstreams; industry regulators lead industry-specific data classification efforts; and several entities join forces to enforce the Data Security Law and the Personal Information Protection Law.

For the time being, Chinese regulators with a stake in data security likely will continue to carry overlapping functions. Facing tight personnel and budget constraints, they must figure out how to collaboratively generate the most regulatory impact.

Relationship with the Central Commission on Technology

A wild card is the new Central Commission on Technology (“the Commission”), whose formation is no less impactful than the data bureau. The Commission is a Party organization, and its administrative office will be a slimmed version of the former Ministry of Science and Technology. Its Party identity empowers it to coordinate investments, talents, and information between and within industries to fast-track indigenous innovation such as semiconductor design and fabrication.

What do the “whole-of-nation” efforts to promote tech innovation mean for the data bureau? The membership of Party commissions is typically not public information, but one has reason to believe that Xi is to personally chair the Commission, and its membership includes high-level officials from the NDRC. An influential presence of the NDRC in the Commission would allow the National Data Bureau’s initiatives to gain political backing, which could be critical to wrestling with resistance in implementation. Furthermore, the Commission could aid by offering state support for developing technologies such as privacy-preserving computing.

China’s history of Party and State Council reforms have revolved around the state’s relationship with the Party, with private and state-owned enterprises, and with market forces. The reforms originate from current deficiencies, and if executed right, would provide impetus to economic growth and social changes. We have witnessed it in the 1980s when China spun off enterprises from the government, in the 1990s when China adapted state bureaucracy to the needs of a market-driven economy, and in the 2000s when China promoted government provision of public services.

With regards to data governance, the 2018 Party and State Council reform emphasized security and gave the Cyberspace Administration the authority to coordinate the implementation of the Cybersecurity Law. The current reform, however, centers on growth and innovation; it is about aggregating and leveraging data to enable high-quality growth and technology innovation. As data security regulation becomes a new normal, China is looking to let its data resources create more value-add to the economy.