Du Fu remains one of the most loved poets in world history. As we look back at his poetry now, we can experience with awe his timeless appeal.

Therefore when I see the portrait of the master

I repeatedly worship it and burst into tears.

Even the minds in ancient times were rarely similar to the master’s,

I would like to resurrect the master and follow him as friend.

—Wáng Ānshí 王安石, “A Portrait of Du Fu” (quoted by Jue Chen, Making China’s Greatest Poet: The Construction of Du Fu in the Poetic Culture of the Song Dynasty [960-1279])

Dù Fǔ 杜甫 (712 – 770) endures in acclaim as perhaps China’s greatest poet. But how has his fame endured? What qualities of his work compel our attention?

To survey Du Fu’s poetry is to simultaneously glimpse Tang Dynasty China while also transcending it, arriving at universal human experience. Exquisitely and economically, he observes nature, honors everyday life, reveals personal hardship and failure, and empathizes with war victims and other suffering souls. Yet his writing is alert to both seriousness and humor, nimbly jumping from one to the other, therapeutically shifting tone and perspective. As readers journey with him, his work expands both awareness and empathy. It elevates, inspires, and rewards. According to the poet Yuán Hàowèn 元好問 (1190 – 1257), “those who study it find their hearts moved and their eyes startled.”

In his 2008 translation, David Young collected 170 of the poet’s works in Du Fu: A Life in Poetry. Grouped in 11 sections in chronological order, his arrangement helps readers trace the poet’s life and development. The graceful, compact free verse employed by the translator adapts well to the modern world, making the poems even more accessible. In these translations, the poems of Du Fu seem to travel effortlessly across time and language, bridging past and present, east and west. So many centuries later, they still serve as empathetic exemplars of our common frail humanity.

Below, a few lines from Young’s translation illuminate Du Fu’s recurring themes, offering a glimpse of his poetry’s genius, along with its deceptive simplicity.

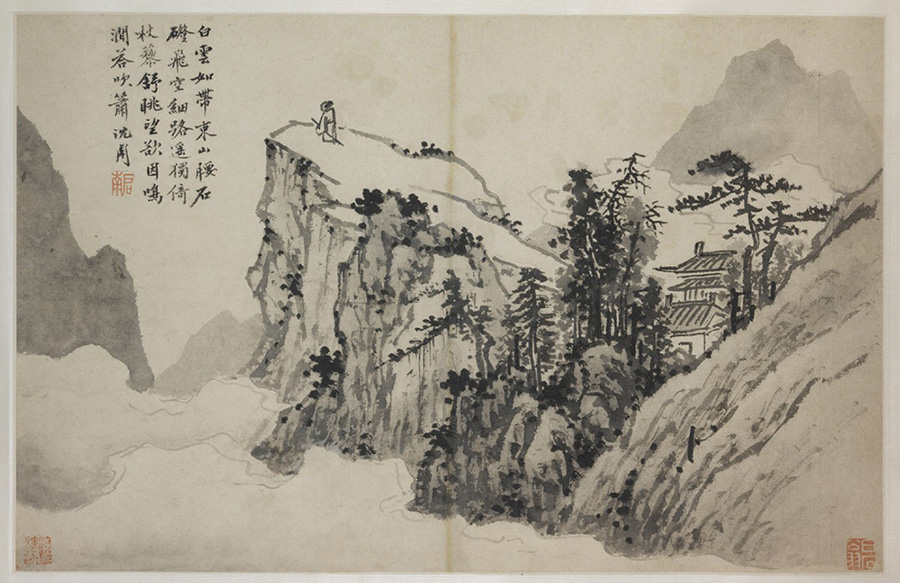

Attuned to nature

Du Fu’s poetry contains an abiding awareness of nature. But the relationship of nature to his poetry is not simple or static. At times, it complements the poem’s narrative or human experience, accentuating it. At other times — sometimes in the very same poem — it contrasts with the human element, suggesting alienation or sadness or smallness. Or it may just be seen and felt and lovingly rendered, fixed in writing for all time. Along the way, a complex relationship between interior and exterior is established, subtle and shifting and textured.

Seasons are sensitively observed. In one spring poem, he self-deprecatingly despairs of describing the flowers he witnesses:

The riverside flowers

are driving me crazybecause there’s no way

to describe their effect

(From Poem 97 in Du Fu: A Life in Poetry)

Yet in the very next poem, he delivers a virtuoso description:

Flowers in crowds, shoals, galaxies

swarm and tangle by the riverI don’t walk I stagger

spring knocks me out

(From Poem 98)

Autumn, too, makes its presence felt. In a sequence the translator titles “Autumn Thoughts,” Du Fu writes:

Dew turns to jade-white ice

that scars and wilts the maple treesthe Wu Mountains and the Wu Gorges

grow bleak in autumn windthe river rises, waves

reaching toward the sky…

my hope of going home

is a lone boat, tied up

(From Poem 134)

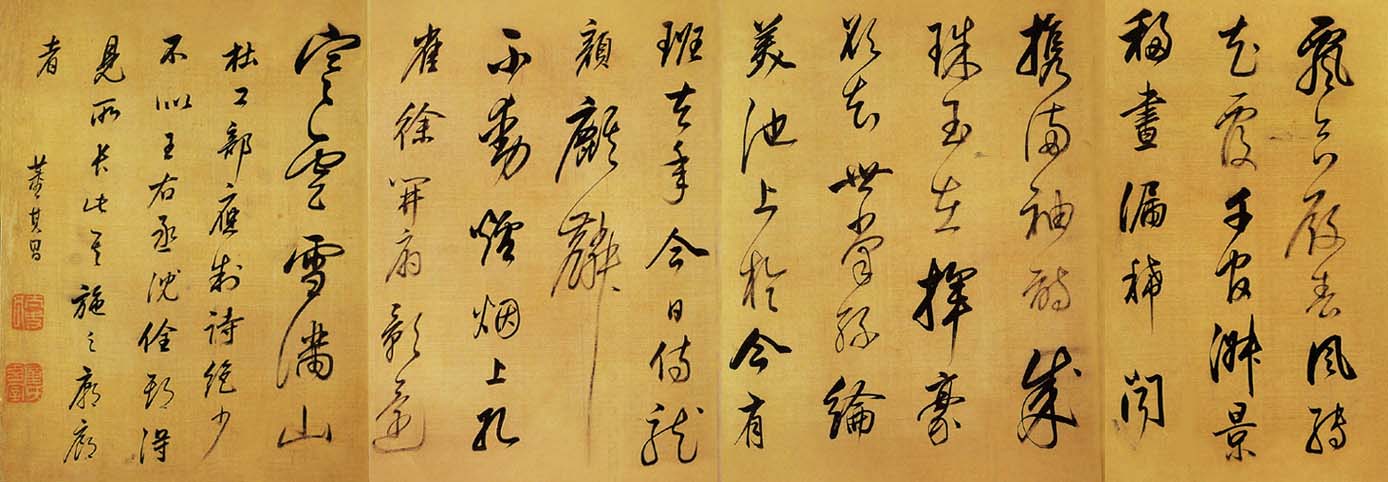

Revealingly personal

Du Fu’s poetry is notably, innovatively personal. This has long been part of his appeal — as the 9th-century poet Yuán Zhěn 元稹 wrote, “Whenever I pursue his poetry scrolls, it is like being on intimate terms (with him).” Many examples from Du Fu’s poetry can be cited, but the poem “Five Hundred Words About My Journey to Fengxian” is a tour de force. David Young writes, “No poem of this kind existed in Chinese poetry before this; it is more personal, more searching, and more comprehensive than anything that had preceded it.”

Du Fu begins in a self-deprecating manner, speaking of himself in third person:

Imagine a man in commonplace clothes,

advancing years,impractical and even stupid,

struggling onhe wanted to rank with sages

instead he has white hair and failurehe’ll stick with his goals, though, until

they close him into his coffina poet who writes from the heart,

anxious about the poorfor which his fellow scholars laugh at him!

(From Poem 48)

He speaks of failure. Though he had long sought an official position in government, he failed the imperial examination twice (in 735 and 747) and, to this point, remained unsuccessful in this quest. Yet the reference to failure may be broader in scope, perhaps extending to the reception of his poetry as well. Following this revealing self-critical introduction, he narrates his journey home from the capital in freezing winter weather. Toward the end of the poem, he approaches home and we’re suddenly caught off guard as the narrative shifts and he hears news from home that “my little son has died.”

and I stand and weep in the street

the neighbors crowd round me, weepingmy shame overwhelms me, a father

who couldn’t feed his familyI who have never paid taxes

never been conscriptedI realize I’ve had an easy life

and I think again of the poorlosing their farms, sons sent to war

no end to their griefstill my sorrow becomes a mountain

whose peak I cannot see.

“Anxious about the poor”

Du Fu used his own experience of obscurity and loss to fuel his concern for others. In this, he seemed to follow the teaching of Confucius: “A humane person wishes to steady himself, and so he helps others to steady themselves…The ability to make an analogy from what is close at hand is the method and the way of realizing humaneness.” Repeatedly, his own adversity served as a bridge toward that of others. At the same time, his attentive observation of others expanded his awareness as well, providing access to experiences he himself did not possess. And circumstance would call for much empathy — the An Lushan rebellion and ensuing civil war (755 – 763) dislocated the imperial court (and Du Fu as well) and left millions of casualties in its wake.

Again, Du Fu’s poem “Five Hundred Words About my Journey to Fengxian,” just before the rebellion, is a fitting example. In it, he narrates his journey home from the capital at year’s end. As he moves from power center to periphery, he contrasts the riches in the capital with the poverty elsewhere:

cabinet ministers live it up

the music drifts through the wintry landscapethe hot baths here are for important people

nothing for common folksthe silk the courtiers wear

was woven by poor womenwhile soldiers beat their husbands

demanding tribute

As he closes this middle section of the poem, he observes:

behind those red gates

meat and wine are left to spoiloutside lie the bones

of people who starved and frozeluxury and misery a few feet apart—

my heart aches to think about it!

Elsewhere, when war brought suffering, he fashioned poems almost of protest:

the emperor wants to expand his realm

though back where we come fromwhole villages are overrun with weeds

while women try to work the farms…

here it is bitter winter

and the Guangxi troops have not returnedtax-gatherers go back and forth

but where will the taxes come from?it makes us question whether

there’s any sense having sonsdaughters can marry neighbors

boys seem born to die in foreign weeds

From Poem 26, “Song of the War Carts”

In this and other poems, he adopts the voice of soldiers at times:

we march away from our parents’ love

shoulder our weapons and swallow our tears…engaging with the enemy

we shoot their horses firstcapturing them

we try to begin with their leaderthere have to be limits to killing

a country has to have boundaries

From a sequence titled “Serving at the Front”

This protest quality of his poems has long been recognized as well. Eleventh-century writer Wáng Huī 王翬 explicated Du Fu’s poetry as employing praise and critique — critique of injustice and inhumanity — and he evidently applauded this quality. For Wang Hui, this practice was consistent with longstanding Chinese literary tradition exhibited especially in the classic Shijing (i.e., Book of Poetry, or Book of Odes). Indeed, this impulse for impartial criticism and counsel reportedly cost Du Fu his brief official position as Reminder (of precedents and traditions) to Emperor Suzong.

Yet while Du Fu has been called a sage (the Poet-Sage) and showed concern for the poor and suffering, he was not quite a saint perhaps. To be evenhanded rather than merely hagiographic, one other point merits notice concerning his relationship to the poor. In the last few years of his life, he evidently owned several slaves and benefited from their labor. It is possible, then, that some of his leisure and some of his poetry from this time are owed to these individuals. As with other writers, a difficult question surfaces — how much did he live up to his image, to his own self-presentation in his poetry? The question may be unanswerable. In any event, the poetry endures, revealing an art both of generous nobility and self-deprecating frailty.

Surprise endings and poetic turns

One of the standout techniques in Du Fu’s poetry is its tendency to take abrupt turns, often at the end of a poem, shifting focus, perspective, or tone. An art of connection, juxtaposition. Sometimes he ends with a question. In the descriptive, imagistic poem “Watching Fireflies,” he concludes with the lines:

white-haired and sad

I try to read their codewill I be here next year

to watch them?

From Poem 148

In “Dreaming of Li Bai,” writing of his friend, the famous poet, he closes with two questions:

if there is justice in heaven

what sent you out to exile?ages to come

will warm themselves at your versesbut what reward is that

for your unappreciated life?

From Poem 65

In other endings, the poet punctuates with image or metaphor or meditation, turning from internal to external or external to internal. In “Leaving Tonguu,” after recounting his ambivalent parting from friends, Du Fu writes:

I turn with shame to watch

the birds among the branches.

From Poem 86

So he turns the focus from his friends back to nature again. But at the same time, the birds call to mind the society he is leaving, thus highlighting his own solitude in contrast.

In “Night at the West Apartment,” as the year ends, after considering nature (the “river of stars overhead”) and struggling civilization (“people weeping for their war dead / in maybe a thousand households”), he abruptly turns to contemplate the smallness of his own experience in comparison:

and like the letters I don’t get

my loneliness means nothing.

From Poem 144

Paradoxically, while admitting and accepting/contextualizing his own loneliness, the poem draws readers together into an unseen sympathy and society for the lonely.

This layered, multi-focused quality of Du Fu’s poetry engages and even challenges readers. The simple, unpretentious elegance of the poetry is undoubtedly beautiful. But beyond its beauty, Du Fu’s poetry encourages a growing consciousness of nature, of self, and of others. Understandably, then, the poems have endured across time and culture as vibrant elegies and engines of empathy.

Coda: The Visage of Du Fu

Take any one of Du Fu’s poems, or even one line, and everywhere you will see his concern for his country and his love for his sovereign, his compassion for the times and his sadness over disorder, his refusal to compromise in adversity, his integrity in poverty, his way of expressing his indignation and refining his nature by means of enjoying the landscape and drinking with friends, even though he had travelled through rugged, war-torn, bandit-infested terrain: this is Du Fu’s visage. Whenever I read him, it leaps before my eyes.

—Ye Xie (1627 – 1703), On the Origins of Poetry (trans. James J.Y. Liu)

A complete collection of Du Fu’s extant poetry is now available online, in both Chinese and English translation. See The Poetry of Du Fu, trans. by Stephen Owen (Boston/Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2016). The collection covers some 1,400 poems and nearly 3,000 pages.