This Week in China’s History: March 30, 1926

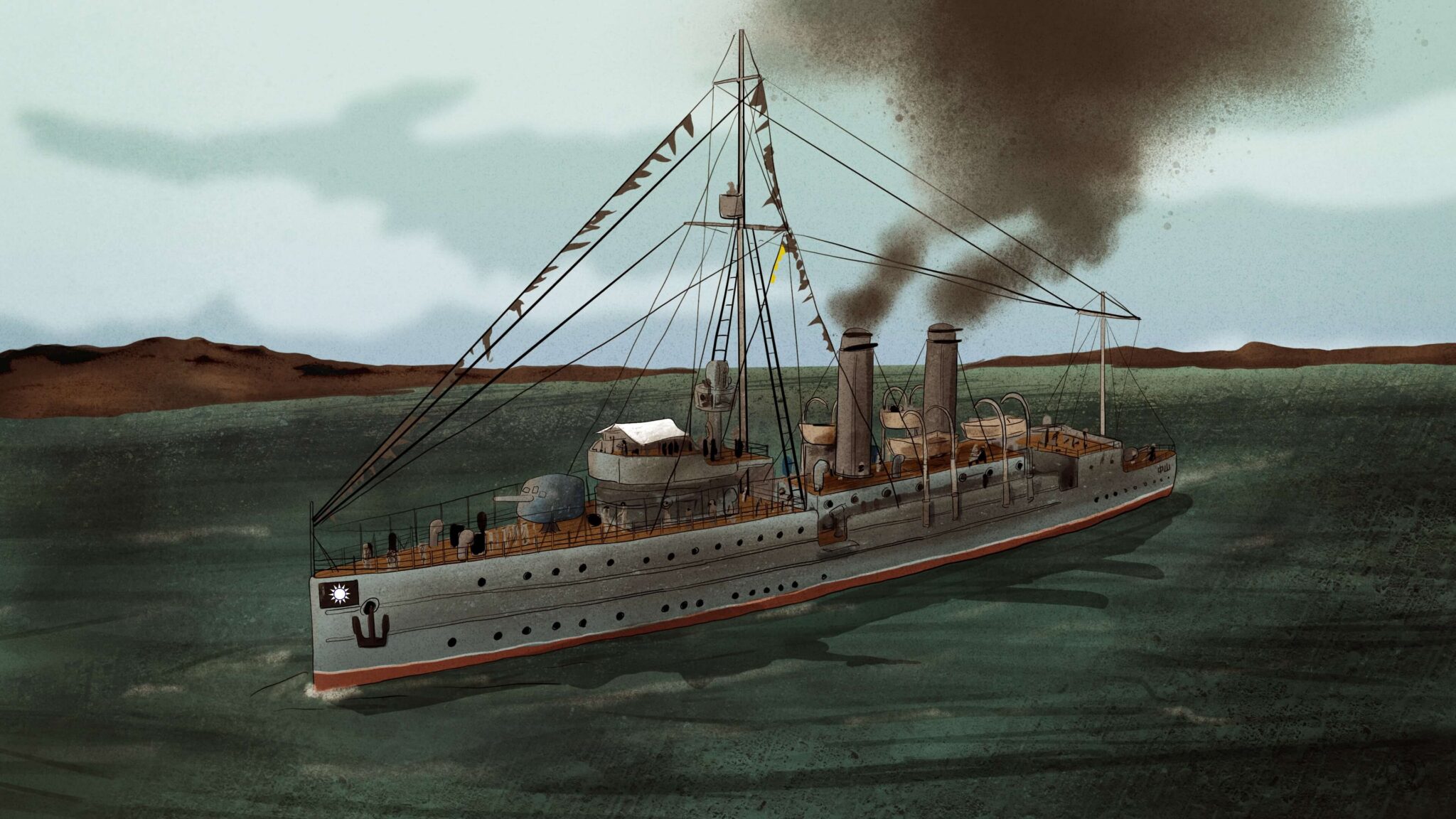

At dawn on March 19, 1926, there appeared in the Pearl River off Whampoa — site of the military academy that was a key feature of the United Front between the Nationalist and Communist parties — a gunship. The SS Zhongshan was the most powerful vessel in the Nationalist navy, in the words of historian Hans van de Ven, and had been renamed a few months earlier to honor KMT founder Sun Yat-sen (孙中山 Sūn Zhōngshān), who had died a year prior.

That the Zhongshan was at anchor off Whampoa on March 19 is about all that is indisputable about the events surrounding what came to be known as the Canton Coup.

To start at the most basic question, why had the ship sailed from its base at Guangzhou, a few miles upriver, to Whampoa?

According to the Zhongshan’s captain, Lǐ Zhīlóng 李之龙, he had moved his vessel to Whampoa at the order of Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí), the Nationalist commander-in-chief, who was himself at Whampoa. Chiang had requested the ship to protect shipping from pirates, some of which had attacked a foreign-flagged vessel the day before and continued to menace the delta.

Perhaps true, but…

The trouble was, Chiang, with the Zhongshan anchored near his offices in Whampoa, was not comforted by the arrival of the most powerful warship in his fleet. To the contrary, he was alarmed: he had not called for any warships to be dispatched to Whampoa.

Or had he…

The arrival of the Zhongshan set in motion a series of events that, though not high-profile today, were as significant as any in shaping modern China’s political path. At the center of the controversy was understanding why the ship had come.

Chiang Kai-shek’s rapid investigation uncovered what he determined to be a plot against him, one that originated in the death of Sun Yat-sen. The KMT had been, since 1924, in the United Front, an uneasy alliance with the Communist Party, and Sun was the only person with the connections and the charisma (and the motivation) to hold this alliance together. When Sun died — of cancer, aged just 58 — the struggle to succeed him was in many ways a fight for the party’s ideological direction, enabled by the ambiguity of Sun’s politics, which enabled communists and fascists to co-exist in his party.

Both sides agreed that the top priority was unifying China after a decade of disintegration, usually called the “warlord era,” but beyond that they shared little in common. On the right, Chiang Kai-shek claimed to be Sun’s chosen successor; on the left, Wāng Jīngwèi 汪精卫 lobbied for more influence.

Chiang would later famously say that while China’s external enemies were a “disease of the skin,” the communists constituted “a disease of the heart,” and barely concealed his mistrust and contempt for his supposed allies. Chiang claimed — in a tactic reminiscent of Gladiator — that Sun, just before he died, had reconsidered his support of socialism and put his faith in Chiang to stave off the threat posed by the Soviet Union.

Wang Jingwei led a faction that was wary of Chiang’s authoritarian tendencies. Supported by the Soviet Union, his “left Guomindang” claimed to represent Sun’s true legacy. The two sides prepared for their Northern Expedition to unite the country, but also plotted against one another. Early in 1926, it appeared that the left might be the stronger side, building on its Soviet influence.

One of those KMT left members was the Zhongshan’s captain, Li Zhilong. Li was a Communist Party member who worked closely with Soviet naval advisors, so when the Zhongshan appeared at Whampoa uninvited, it raised alarm bells for Chiang. The alarm bells were amplified by a series of unusual phone calls from subordinates asking for details and confirmation of Chiang’s plans and movements. Although the ship soon went back to Guangzhou, Chiang launched an investigation into just what had been going on.

The investigation revealed a Soviet-backed plot by the Communist Party. The Zhongshan had not come to fend off pirates but to take Chiang Kai-shek prisoner. Chiang would be taken to Vladivostok, the USSR’s Pacific port, where he would be held until satisfactory arrangements for KMT leadership could be made.

As I said, though, little about this event is agreed upon.

In the PRC, the event is seen as a “false flag” operation, orchestrated by Chiang so that he could eliminate the Communist and Soviet elements in the party. In this telling of events, Chiang arranged for the Zhongshan to be dispatched, just as Li Zhilong and others claimed, but then denied it and used the ship’s appearance to declare that the communists in the KMT were plotting his ouster. The “discovery” of the plot, including the rather farfetched notion that he was to be spirited away to Vladivostok, more than 2,000 miles away by sea, was an excuse to launch his purge and cement his status as Sun’s successor.

Historian Yang Tianshi has offered another hypothesis, suggesting that neither Chiang nor the communists were plotting. Yang’s theory can be summarized by one of my favorite maxims — never attribute to malice what can be reasonably explained by incompetence. In his 1988 article (republished in English in 1991) “The Riddle of the Zhongshan Gunboat Incident,” Yang argues that miscommunications and ineptitude, fueled by some mid-level score-settling and paranoia, rather than high-level scheming on either side, led to the deployment of the Zhongshan.

But whether the ship was part of a plot or not, Chiang acted quickly to head off dissent in his ranks. He declared martial law in Guangzhou on March 20 and launched a purge of communists in the Whampoa academy. Cadets loyal to Chiang, as well as Nationalist soldiers, arrested the political leaders at the academy, including Li Zhilong. Several Communist divisions at Whampoa were purged, and Soviet advisors were expelled. Although the United Front would continue until the Shanghai massacre of 1927, the prospects of the KMT left never recovered after Chiang’s “Canton Coup.”

It’s of course impossible to speculate what might have happened had the KMT left remained a viable part of a coalition. In all likelihood, that ideological distance between the right and left would have eventually ended the United Front, and in any case the Japanese invasion of the 1930s reshuffled the deck completely. Nonetheless, given the prominence Chiang Kai-shek came to assume, the event that secured his role ought not be forgotten.

And the Zhongshan itself has a noteworthy coda: serving in the Chinese navy, she was sunk by Japanese bombs in 1938 in the Battle of Wuhan, and remained at the bottom of the Yangtze for nearly 60 years. In 1997, the ship was raised and re-floated, eventually taking its current place on the Wuhan waterfront as a floating museum.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.