How good is Ernie, China’s answer to ChatGPT?

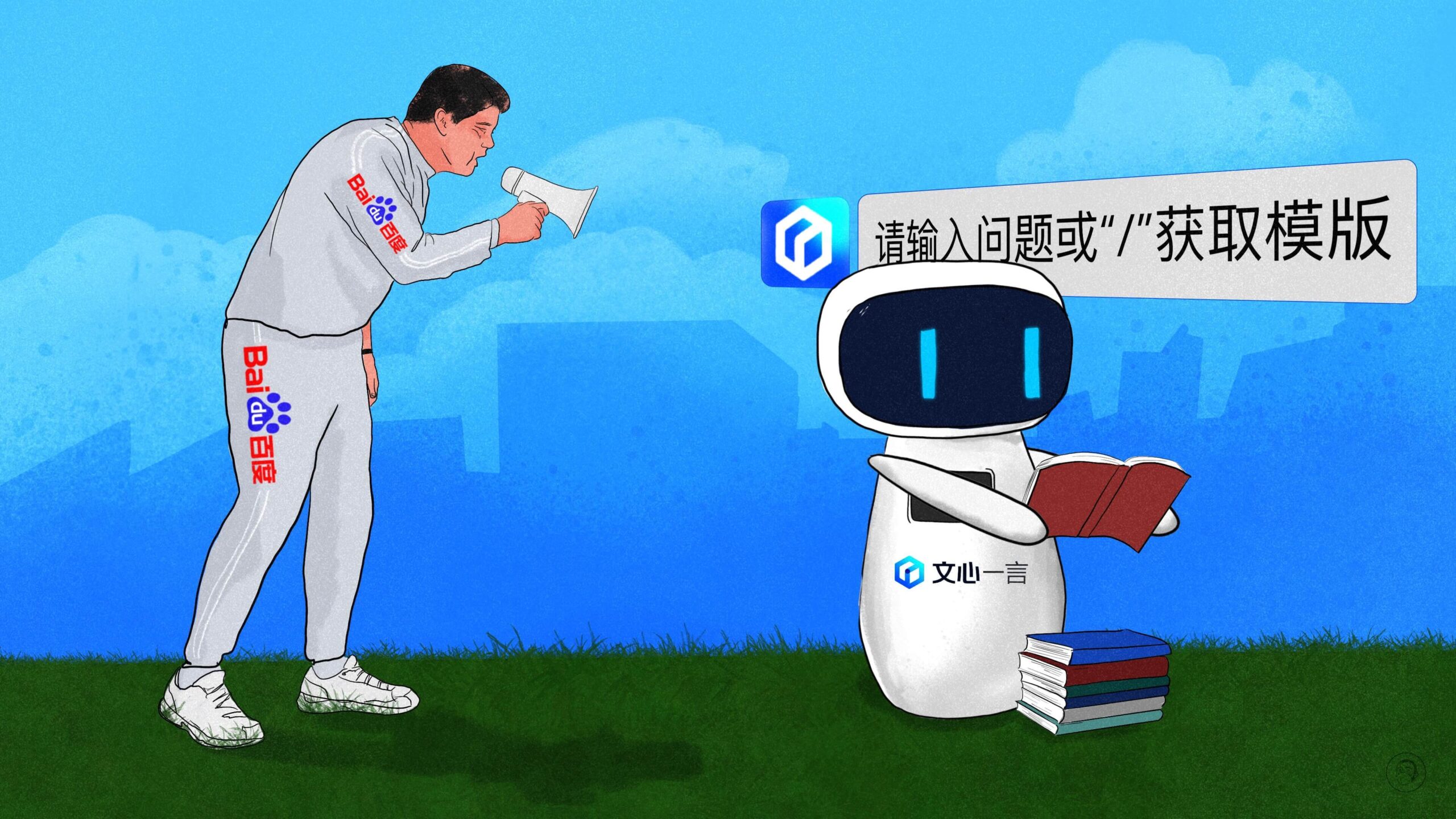

On March 16, search giant Baidu launched Ernie Bot — an artificial intelligence platform like ChatGPT. Ernie is China’s chat bot market leader, and we now have a sense of how well it works.

ChatGPT has taken the global classes by storm, as lawyers, bankers, coders, writers, and artists worry about artificial intelligence (AI) taking jobs and different types of bots based on Large Language Model (LLM) technology proliferating in Silicon Valley and beyond.

Just a week ago, tech industry luminaries like Elon Musk, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, and more than 10,000 others called for a six-month pause on chat-bot development so humans can assess how dangerous the new AI models might become.

A six-month pause might be all that Baidu needs to catch up with ChatGPT and other American peers. Baidu is China’s leading search engine and — so far — leading AI chat bot developer, having launched its Ernie Bot (文心一言 wénxīn yīyán) on March 16. The company’s founder and CEO Robin Li (李彦宏 Lǐ Yànhóng) recently suggested that the current gap between Ernie Bot and ChatGPT is “maybe two months at most.” Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.China news, weekly.

Ernie Bot beats expectations, falls short of aspirations

But initially, Baidu’s unveiling of Ernie was a disappointment. It was announced without a live demo nor was there a public release. This led to fears that the product was not ready for market. Indeed, reports leading up to the launch suggested that staff were being worked around the clock and denied leave for Chinese New Year in the scramble to meet the March 16 deadline.

However, since its release, Ernie’s reception from users has been broadly positive. An in-depth post on forum website Zhihu, replete with screenshots from interactions with the model, says that Ernie’s response time is fast — faster than GPT-4 in some instances — and that information storage is also not a problem, enabling previous responses in a conversation to be “remembered.” As for Ernie’s capacity to solve math questions: “Dare I say, this performance is even better than GPT-3.5.”

Nevertheless, while awarding Ernie a score of 65/100, the writer acknowledges a significant lag in comparison with GPT-4, which they would grade 90/100, and says the quality of its responses are often clunky, and that ability to assist in writing code is still rudimentary.

Image generation has another bug: While impressive and a step beyond GPT-4’s capabilities, Ernie appears to translate prompts into English before producing pictures. This is indicative of one of the main issues for Ernie and for Chinese LLMs more generally: the paucity of quality training data.

The big issues facing Ernie Bot

Baidu is China’s largest search engine but it has not functioned as the gateway for internet traffic in the same way that Google has, thanks to WeChat and other online services that are not on the open internet.

Tools such as those provided by Common Crawl, a nonprofit that “crawls” the web to freely provide datasets to the public (and thus to LLMs such as ChatGPT), would not be feasible for China’s siloed internet space, especially in the mobile era, where most data are stored in individual apps and distributed by various app stores.

Furthermore, according to market research firm BAiGUAN, Chinese language training data is inferior to English training data in most domains, including social media content, literature corpora, academic corpora, news data, and Wikipedia data. Indeed, a Peking University professor cited by news outlet Jiemian noted that English content accounts for 60.4% of the top 10 million websites in global rankings, compared with just 1.4% of Chinese content.

Censorship is another concern for Chinese LLMs. The Washington Post, which gained access to Ernie, noted that any sensitive prompts or questions will terminate the conversation, with a button appearing: “Start a new conversation.”

Baidu has no choice but to be cautious: Regulators have already told major Chinese tech companies including Tencent and Ant Group not to offer ChatGPT services to the public; Xiaobing, a chatbot launched in 2014, was soon banned for displaying an “unpatriotic attitude.” Another model, ChatYuan, was suspended within days of its launch.

Censorship is a widespread issue in China, but it is particularly fraught when it comes to LLMs, because their outputs cannot be completely controlled. An inability to have one’s model tested by the public forecloses a significant avenue for improvement — ChatGPT had over 100 million users providing additional data to its model within three months of its launch. As such, there is likely a trade off between these models’ usefulness and the desire for control over content.

Ernie might just be good enough to make money

Within China, GPT-4 is not accessible. As such, Baidu is well placed for the domestic market. Jeffrey Ding, an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University focusing on emerging technologies, told the China Project that Baidu’s first mover advantage here is crucial: “Baidu has been focusing on LLMs for several years. A lot of the work and experience is in the tacit knowledge, the organizational knowledge to make your training runs more efficient. If you haven’t accumulated the technical expertise to build these LLMs, how are you going to create a ChatGPT?”

When it comes to specific applications of LLMs though, perhaps concerns about censorship, or even the broader criticisms leveled at ChatGPT, are largely irrelevant. When I put this to Ding, he agrees: “Maybe you don’t need wide-scale public adoption of LLMs,” he says. “Maybe you only need to commercialize the technology in certain sectors.”

A report from Leonis Capital, a venture capital firm, also supports this point of view, arguing that from a business perspective, the lag in Chinese LLMs makes little difference. According to the report, building vertical-specific models with large amounts of domain data “often make up for the performance gap and usually produce better real-world application results.”

This report points out that open-source models from the West have also enabled Chinese developers to take shortcuts, such as simply adapting existing models to the Chinese context. For example, the image generator Taiyi-Stable Diffusion builds on top of the pre-existing open source model Stable Diffusion, released in August 2022 by the startup Stability AI in collaboration with researchers in Europe and the U.S.

The greater use of video-based marketing also means that there is more focus on creating digital humans and AI avatars, which are used extensively in China’s media, entertainment, and ecommerce sectors.

Besides Baidu, there is a burgeoning sector in China working on these products. Ding sees the technology conglomerate Inspur as Baidu’s closest competitor. Meanwhile, Alibaba’s research division DAMO Academy has released a text-to-video synthesis on the open source platform HuggingFace, but it currently only supports English input. Meituan co-founders Wáng Huìwén 王慧文and Wáng Xìng 王兴 have announced that they are working on a similar project. And veteran investor Kai-Fu Lee (李開復 Lǐ Kāifù) has announced that he is building a new AI company called Project AI 2.0 that will focus on developing ChatGPT-like apps. However, it is unclear when these firms will release products, with little in the way of actual detail among the various announcements so far.

Universities have released models too, such as one from Peking University’s Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI), and Tsinghua’s open source ChatGLM-6B model. However, academic institutions will be hampered by the lack of money to spend on the vast quantities of both computing power and human resources required.

The real dark cloud?

Perhaps the biggest drawback for the industry in China at the moment is more fundamental. Jeffrey Ding notes that cloud computing is a key enabling factor to run LLMs. “If you’re not going to train them yourself and you want to access someone else’s, then cloud computing is key for the diffusion of these models. And cloud computing rates in China, as well as overall digitization rates, are just much lower than in the U.S.” This contrast in technological diffusion for AI more broadly is also underscored in the Stanford report: last year there were 542 newly funded AI companies, compared to only 160 in China.

And when it comes to the U.S.-China competition, cloud computing is coming into focus as a potential issue: most Chinese companies have relied on advanced GPU chips to train their models. However, despite the export controls put in place last October restricting China’s access to these chips, many companies have found a workaround by using offshore cloud computing to train their models instead.

It is unclear whether this access will be maintained, or if the U.S. will tighten restrictions further. And this level of uncertainty is unhelpful for businesses.

But Baidu remains bullish. Robin Li has said that he has full confidence that Baidu Cloud will become China’s leading cloud provider. In fact, he sees cloud computing technology as the most important aspect of the AI technology race.

Companies:

Sources and additional data:

- The diffusion deficit in scientific and technological power: re-assessing China’s rise / Jeffrey Ding

- AI Index Report 2023 – Artificial Intelligence Index / Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence

- Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter / Future of Life Institute

- Baidu ERNIE Bot Press Conference / Baidu

- Baidu, Inc. (BIDU) Q4 2022 Earnings Call Transcript / Seeking Alpha

- “文心一言”未至先火,大语言模型加持将开启百度发展新纪元 / The Paper

- 百度推出企业级大模型服务平台“文心千帆”:按调用输入输出总字数付费 / Caijing

- The bearable mediocrity of Baidu’s ChatGPT competitor Ernie Bot / MIT Technology Review

- China’s Baidu launches AI chatbot, Ernie Bot, to rival with ChatGPT / The Washington Post

- Baidu’s ERNIE Bot: True Competition? / Dr. Ian Cutress

- ERNIE Bot vs ChatGPT / Tony Juntao Peng’s Recode Newsletter

- 对话李彦宏:不要重复造轮子,AI的十倍机会在别处 / 36kr

- 百度「文心一言」的真实内测使用体验如何? / Zhihu

- ChatGPT doesn’t understand Chinese well. Is there hope? / Baiguan Substack

- ChatGPT banned in Italy over privacy concerns / BBC News

- Chinese views on ChatGPT and Baidu’s upcoming alternative / Pekingnology

- Baidu to integrate ChatGPT-style Ernie Bot across all operations / Nikkei Asia

- 微软新必应中文版体验:集成AI和实时搜索,比ChatGPT强在哪 / The Paper

- 创新工场李开复:AI 2.0已至,将诞生新平台并重写所有应用 / Sinovation Ventures

- The generative AI landscape in China / Leonis Capital

- 甲小姐对话张斯成:ChatGPT过热容易导致错误判断 / Jazzyear

- Surrender your desk job to the AI productivity miracle, says Goldman Sachs / Financial Times