At Megaport, Taiwanese bands celebrate the island’s history and culture

40,000 people attended the Megaport Festival in Kaohsiung on the first weekend of April, where several bands sang in Taiwanese Hokkien about political issues, from the February 28 massacre to the legacy of colonialism.

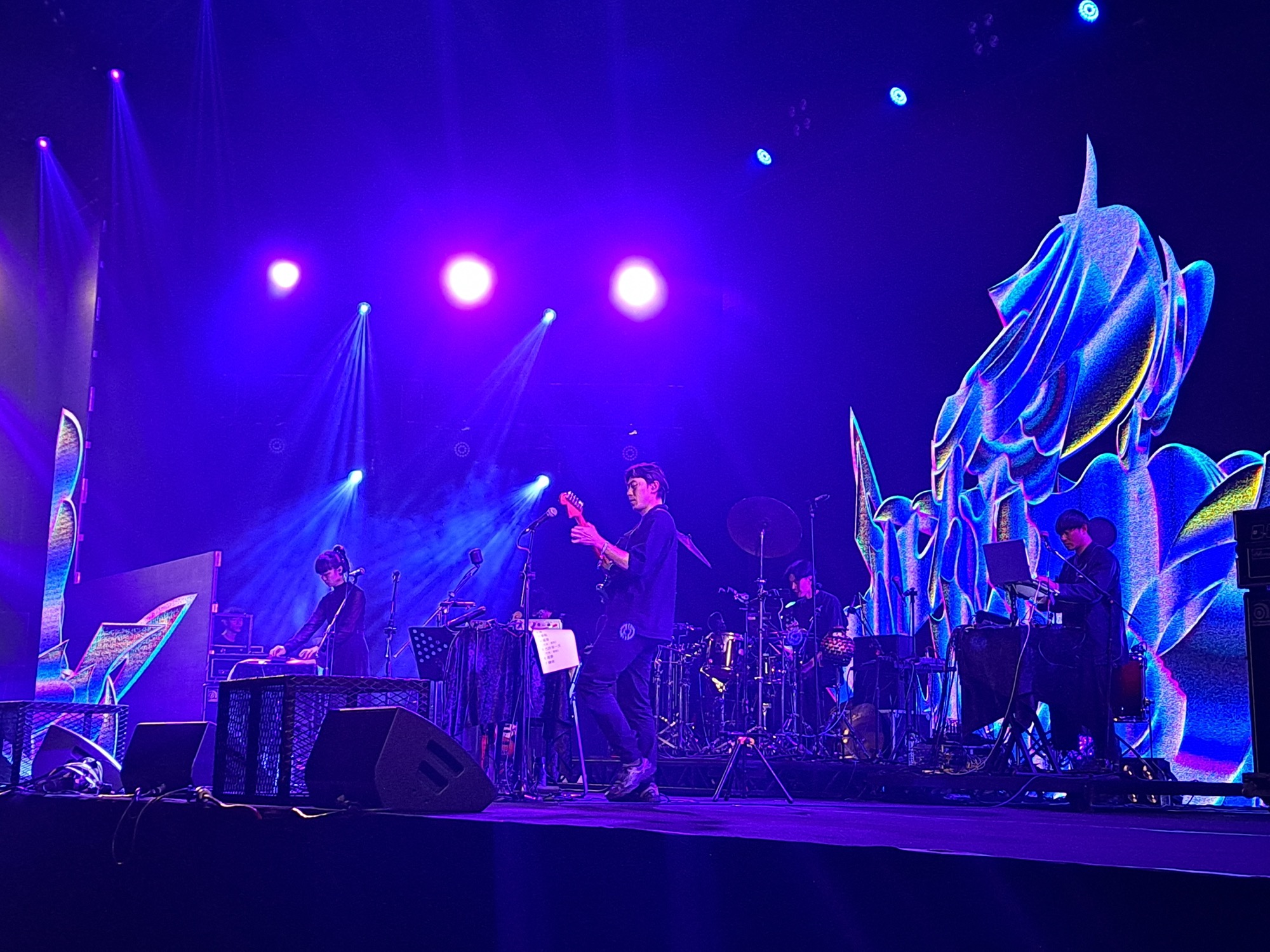

In a packed auditorium at the Kaohsiung Music Center in Taiwan’s second-largest city, hundreds of heads swayed to the rhythms of a slow-building rock song. The five-person band on stage was mixing guitar melodies with traditional Taiwanese instruments like the suǒnà 嗩吶 trumpet and small finger cymbals and bells that wouldn’t sound out of place at a temple festival.

But this wasn’t a temple. This was the Megaport Festival, one of the largest music festivals in Taiwan. Held on the first weekend of April, it brought together 40,000 people to see some of the island’s most popular independent bands.

The band on stage was Tsng-kha-lâng, performing in Taiwanese Hokkien in front of a projected video of falling cherry blossoms and a countryside train. In the video, an old woman offers food at a temple, and then this scene is intercut with her younger self tending to the body of her recently executed husband. A blood-stained burlap sack covers his face, while a bullet wound near his heart stains his white shirt red. This scene is set during the February 28 massacre of 1947 (known simply as “228”) — a distinctive mix of art and politics that the festival has become known for.

Megaport has been held almost every year since it was cofounded in 2006 by the Taiwan Rock Alliance. One of its high-profile cofounders is Freddy Lim (林昶佐 Lín Chǎngzuǒ / Lîm Tshióng-tsò), a lawmaker and longtime activist for the Taiwan independence movement, who happens to be the lead singer of one of the island’s most popular heavy metal bands, Chthonic (閃靈 shǎn líng).

The festival has deep roots in the rock scene of southern Taiwan, a region that’s traditionally a bastion of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the independence movement, and has taken on an association with Lim’s outspoken politics. But it’s a music festival first and foremost, and it draws some of the largest crowds of any in Taiwan. In this most recent edition, which sold out in minutes, 10 stages were distributed throughout the pier district, both indoors and outdoors; fans mingled on the boardwalk, where just beyond, gigantic container ships slowly made their way to and from the port.

Although it’s just a couple of hours away by high-speed rail from the rainy, cool northern capital of Taipei, Kaohsiung is culturally very different. It’s more industrial, the pace of life is slower, and people are more likely to speak Taiwanese Hokkien, while the traditional culture of Taiwan’s earliest waves of Han Chinese settlers is more visible. The festival reflects this, showcasing emerging independent bands that emphasize Taiwan’s unique history, culture, and identity.

When I talk to young Taiwanese people, many of them tell me they are much likelier than their parents to identify as only Taiwanese rather than Chinese. But they also say the island is still deciding what this identity means. Over the course of the weekend, I observed how several popular independent bands — Sorry Youth, Collage, Tsng-kha-lâng, and Prairie WWWW — are using independent music to connect young Taiwanese listeners with the island’s unique history, languages, and social issues. These bands are all stylistically unique, but they are similar in that they are at the forefront of a generation’s efforts to figure out what it means to be young and Taiwanese.

I had a chance to talk to musicians from two of the bands listed above, chat with their fans, and see all of their sets. Here’s what I learned.

Sorry Youth (拍謝少年 pāi xiè shàonián)

Formed by a trio of university friends who met in Taipei 15 years ago, rock group Sorry Youth is one of the few indie bands that sings all of its songs in Taiwanese Hokkien. The band’s bassist, who goes by the stage name Giang Giang (薑薑 jiāng jiāng), told me that they started singing in Taiwanese Hokkien because they felt it was naturally more musical.

“Speaking Taiwanese just sounds like a kind of melody. It has more tones than Mandarin, so speaking regularly in the language is like singing,” Giang Giang said. Taiwanese Hokkien traditionally has eight tones, compared with Mandarin’s four.

The band’s drummer, who writes his name in English as Chung-Han (宗翰 zōng hàn), added that their parents were all forbidden from speaking Taiwanese Hokkien in school due to the Nationalist government’s Mandarin-only policies during that time. Many older Taiwanese people remember being hit by teachers for speaking their mother tongues during class, or having to wear a sign around their necks promising not to speak in their “dialect.” Even after martial law was lifted in 1987, it wasn’t immediately easy for many children to learn the language in schools.

As a result of this, Giang Giang said, “We think singing in Taiwanese is a very important thing, because it can convey our values and the story we want to tell through this specific language.”

“After this long period of time, we think it’s important for people to gradually get Taiwanese back to our daily life,” Chung-Han added. “Especially after the language had been suppressed by the government for such a long time.”

They had grown up speaking Taiwanese Hokkien in their homes, with their families, but writing lyrics in the language proved a challenge. The band enrolled in classes and started reading novels written in the language.

Their music has resonated with Taiwanese listeners. Their 2017 album Brothers Shouldn’t Live Without Dreams (兄弟沒夢不應該 xiōngdì méi mèng bù yìng gāi) won a Golden Melody Award and a Golden Indie Music Award, two of Taiwan’s highest musical honors. In 2021 they released Bad Times, Good Times (歹勢好勢 dǎi shì hǎo shì), which they worked on during the isolation of the pandemic. Fans crowdfunded the production of that album to the tune of 3 million NTD ($98,000).

Sorry Youth is unafraid to tackle social issues, with songs frequently based on historical or current issues. In the music videos for one of its most recent songs, Pilgrimage (出巡 chūxún), Tsai Kuan-yu (蔡寬裕 Cài Kuānyù), who was a political prisoner for 13 years, tours an old prison, accompanied by members of the experimental dance group Piànn-tiûnn (拚場 pàn chǎng) dressed as temple gods and guardians. The group cites, among its influences, Taiwanese Hakka folk singer Lín Shēng-Xiáng 林生祥, who also played at Megaport this year, famous for participating in a campaign that saved his Hakka-majority village, Meinong, in southern Taiwan from a government-planned dam megaproject.

Sorry Youth’s band members often participate in political events and have spoken openly about their support for movements such as Taiwanese independence. They participated in the 2014 Sunflower Movement, which saw hundreds of students occupy Taiwan’s legislature for weeks to protest a trade deal with China.

“I think that movement was the big inspiration for all of the people in Taiwan to make everybody believe that we do care about this, this island, this country,” Giang Giang said. “At that time, I was still working [a day job], and every day after work I’d go to the Legislative Yuan.”

“I think it demonstrated that Taiwanese people want to choose our destiny by ourselves, not [have it decided] by the government or even China,” Chung-Han added.

Collage (珂拉琪 kē lā qí)

One of the highlights of the festival’s first night was chamber pop duo Collage, a collaboration between Natsuko Lariyod (夏子·拉里又斯 Xiàzi·Lālǐyòusī), who has mixed Hakka and Amis Indigenous ancestry, and Hunter Wang (王家權 Wáng Jiāquán), who has Taiwanese Hokkien-speaking ancestry. One of the band’s early major successes came in 2018, when it won an award for a cover of the Chthonic song One Thousand Eyes (合掌 hé zhǎng). This history came full circle on April 1 when it performed alongside Freddy Lim and Chthonic as the closing set of Megaport’s first day.

Seeing the bands side by side, I couldn’t help but notice continuity as well as change between the generations. Groups like Chthonic created the space to sing unapologetically in Taiwanese, about Taiwanese themes and history, blending heavy metal with traditional instruments like the erhu. In the newer generation, groups like Collage aren’t afraid to push these methods into more experimental directions, and engage more in genres such as indie rock, chamber pop, and electronic.

Collage’s songs are often about Taiwan’s history under martial law — and even further back, its rule by colonial powers under Japan, the Qing dynasty, and European powers such as the Spanish and Dutch. Their lyrics are written in a mix of several languages, including Taiwanese Hokkien, Amis, and Japanese, which many elderly Taiwanese people can still speak or understand as a result of 50 years of Japanese colonialism. The band took home the Best New Artist award at Taiwan’s most recent Golden Melody Awards for its debut album MEmento·MORI.

Mixing languages comes naturally to the band’s vocalist Natsuko Lariyod, who said in an interview with Zepp Asia that her Amis Indigenous grandmother was born when Taiwan was still a Japanese colony, and as a result received a Japanese education. Lariyod recalled growing up speaking a mixture of Amis and Japanese with her grandmother and not knowing where one language ended and the other began, to the point of even thinking her Japanese first name, Natsuko, was a traditional Amis name. Lariyod’s first single using Amis lyrics was “Maliyang,” and she said that she asked her Amis father for help with the lyrics since she wasn’t completely fluent in the language.

Many of the songs in MEmento·MORI deal with death, including songs about victims of the Nationalist troops’ February 28, 1947 massacre of thousands of Taiwanese protesters and civilians, and the ensuing 38-year martial law period, known as the White Terror. Some of the album’s most popular songs, “Buried in the past, the fire is still there” (葬予規路火烌猶在 zàng yǔ guī lù huǒ xiū yóu zài / tsòng hōo kui-lōo hué-hu iû-tsāi) and “A thousand flowers and a mother’s sorrow” (萬花蕊慈母哀 wàn huā ruǐ címǔ āi / bān-tshian hue-luí tsû-bió pi-ai), are about the bereaved families of the victims of the White Terror and the wife, mother, or child that they left behind. The lyrics are highly allegorical and poetic, and contain many references to religion, Taiwanese history, and culture — so much so that online communities have formed to discuss possible interpretations.

Tsng-kha-lâng (裝咖人 zhuāng kā rén)

Tsng-kha-lâng is a relatively new band, formed in 2017, whose members mostly met as students at the department of Chinese Literature at National Dong Hwa University. In Mandarin, its name is a homonym for “the Pretenders,” but in Taiwanese it simply means “people from the countryside.” It’s one of many ways that an interest in literature shapes the band’s style: the band’s vocalist, Tiunn Ka-siông (張嘉祥 Zhāng Jiāxiáng), said in an interview that his group isn’t “quite like a band…We rarely go to music festivals to watch performances. The way we create is more like writing a novel.” So much so, in fact, that Tiunn actually accompanied the band’s debut album with a published novel of the same name, and the processes of creating the novel and the album actually influenced each other.

The band was shortlisted for the 2022 Best New Artist award at the Golden Melody Awards (which eventually went to Collage).

They’re easily recognizable as a rock band, but they blend indie rock with a heavy use of traditional Taiwanese “Pak-koán” (北管 běi guǎn) instruments that one would normally see at Taiwanese temple ceremonies or funerals, such as the distinctive suona trumpet, with its loud, discordant, and attention-grabbing melodies, and small finger cymbals.

Sorry Youth uses these instruments too, but while its sound is still predominantly rock (its BandCamp page describes its sound as “Taiwanese hits that even grandmas and grandpas will approve”), Tsng-kha-lâng puts more emphasis on the traditional instruments, and goes for slower melodies with sparser lyrics, often mixing songs with monologues or spoken word. It’s an effective mix, sounding neither so traditional that it feels ethnographic nor conventional enough to be confused with other rock bands.

The title of its first album, Iā-Kuan Sûn-Tiûnn (夜官巡場 yè guān xún chǎng), means “night spirits on patrol,” referring to the folklore of nighttime temple ceremonies and ghosts, spirits, and the otherworldly. Similarly to Collage’s debut album, it blends stories from the lead singer Tiunn Ka-siông’s life growing up in the village of Minxiong, in Taiwan’s southern Chiayi county, with stories from the area and historical events.

At its performance, the band’s most striking song was Lîm Siù bī (林秀媚 Lín Xiùmèi), dedicated to the widow of Taiwanese lawmaker Lú Bǐngqīn 盧鈵欽 (Lôo Píng-khim), who was executed by KMT soldiers after trying to mediate between them and the rebelling villagers of the Chiayi region during the 228 massacre. The band played in front of a music video showcasing different actresses playing the role of Lin Xiumei, both after the execution and as an elderly woman many years later, still mourning his loss. As the song progressed, fans tossed fistfuls of gold-colored paper joss money into the air, which glowed brilliantly when hit by the stage lights, almost as if they were burning in a temple’s furnace.

Prairie WWWW (落差草原 WWWW)

Somewhat different musically and stylistically from the other bands here, but still committed to engaging with local Taiwanese cultures and history, is the experimental rock group Prairie WWWW. Composed of five members and formed in Taipei in 2010, Prairie WWWW’s style combines folk influences with ambient electronic elements, poetry, and field recordings from nature. The four W’s in its name aren’t pronounced, but are meant to evoke both the waveform of music and the shape of blades of grass blowing in the wind. The band’s members also all use stage names.

During a backstage interview, the band explained that one of its latest songs, Formosan Dream (黑夢 hēi mèng), which it played during its set on April 2, draws from the Taiwanese writer Wáng Jiā-Xiáng 王家祥, who explored the earliest stories about the island as told by Indigenous oral storytellers. The single’s lyrics evoke the mists and star-filled skies of ancient Taiwan, accompanied by distinctive electronic synths and ghostly, sometimes distorted vocals. Production for the band’s songs often involves trips throughout the island to conduct field research on local cultures and stories.

In contrast to the other bands here, Prairie WWWW’s lyrics are mostly in Mandarin, though they sometimes sing in Taiwanese Hokkien or collaborate with Indigenous artists who sing in their own languages. One of their highest-profile collaborators, who was onstage with them at Megaport, is the singer-songwriter and Indigenous rights activist Panai Kusui, of the island’s southeastern Puyuma and Amis nations. Panai supported current President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) campaign in 2016, playing songs at several of her rallies and her inauguration. After her election, Tsai fulfilled an election promise to formally apologize to Indigenous peoples for “four centuries of pain and mistreatment.” However, after further demands for Indigenous land rights went unmet, Panai occupied a tent facing the presidential office for over a hundred days in protest.

The band’s members don’t identify as Indigenous. The band’s guitarist, who uses the stage name Wéi-Xiáng 唯祥, said that even before starting the band he worked with Indigenous people during his day job, and often listened to the traditional songs they would sing or stories they would tell. He mentioned that the recurring themes of balance between humans, animals, and the natural environment drive much of the band’s work. When working with Indigenous narratives and cultures, bands in any nation run the risk of appropriation. When I asked about this, Wei-Xiang replied that the band thinks very carefully about this in all of their work, credits Indigenous artists or cultures if they reference a specific story, and tries to weave Indigenous and local inspirations into original works that also draw from the band’s own creativity and reflection process.

Reflections on music and identity

As the festival wrapped up late on Sunday evening, thousands of fans slowly made their exit from the main stage on the pier, taking light rail, trains, or cabs to other parts of the city. I took a moment to rest on a bench overlooking the harbor, and watched the sky slowly grow darker while the reflection of the lights on the water grew brighter.

This festival happened to take place on Qingming, a holiday dedicated to remembering ancestors. I couldn’t help but remember that, along with the port of Keelung in the north, this very harbor was where Chinese Nationalist troops arrived in 1947 to break a stalemate with protesters — with violence, ultimately killing thousands across the island. Kaohsiung was one of the first cities where the openly brutal wave of violence from the 228 massacre began. Kaohsiung’s then-City Hall building, which is now a history museum with a permanent exhibit on 228, was the site with the highest recorded number of casualties during the massacre. It was surreal to think that this site was now welcoming thousands of young people to celebrate musicians who were unapologetically confronting these events, singing in languages that the Nationalist government had tried its best to stamp out.

At the same time, I reflected on the limits of music’s influence on social issues. Taiwan has passed several laws intending to protect mother tongues, but most of these languages — especially Indigenous languages — still face declining numbers of native speakers. Sorry Youth’s Chung-Han told me he doesn’t feel that enough resources have been set aside for mother tongue education in Taiwanese schools, but he hopes singing in Taiwanese will inspire other young people to sing in their own mother tongues.

Many of the performances reminded me of a popular expression often used to refer to Taiwan: “Ghost Island” (鬼島 guǐ dǎo). Supposedly first used by Japanese settlers who were dismayed at the high rates of infection and death during the colonial period, its connotations have shifted in recent years to a self-deprecating term for young people to refer to the many social issues in Taiwan: low salaries, dim career and housing prospects, and increasing threats from China. It’s often used in a way that implies a sense of despair about the future.

At the festival, I felt myself thinking about the term in two additional ways: in a much more literal sense, many of these bands were grappling with Taiwan’s “ghosts,” the restless spirits of those lost during the martial law periods as well as the ongoing work of transitional justice and historical memory. And in the other sense, related to a feeling of despair about the future. But for one weekend, anyway, thousands of young people had no reason for anxiety. Not everyone I talked to at Megaport was politically engaged — many were just there to have a good time — yet it was stirring to see crowds of thousands collectively participating in the difficult, ongoing process of figuring out what it means to be Taiwanese.

Ray Wei-Chieh Wang contributed translation, and Antonio Tze-Yi Yang contributed translation and research for this piece.