This Week in China’s History: April 18, 1942

Around nightfall on April 18, 1942 — it was a Saturday — American bombers crashed into dozens of sites in eastern China.

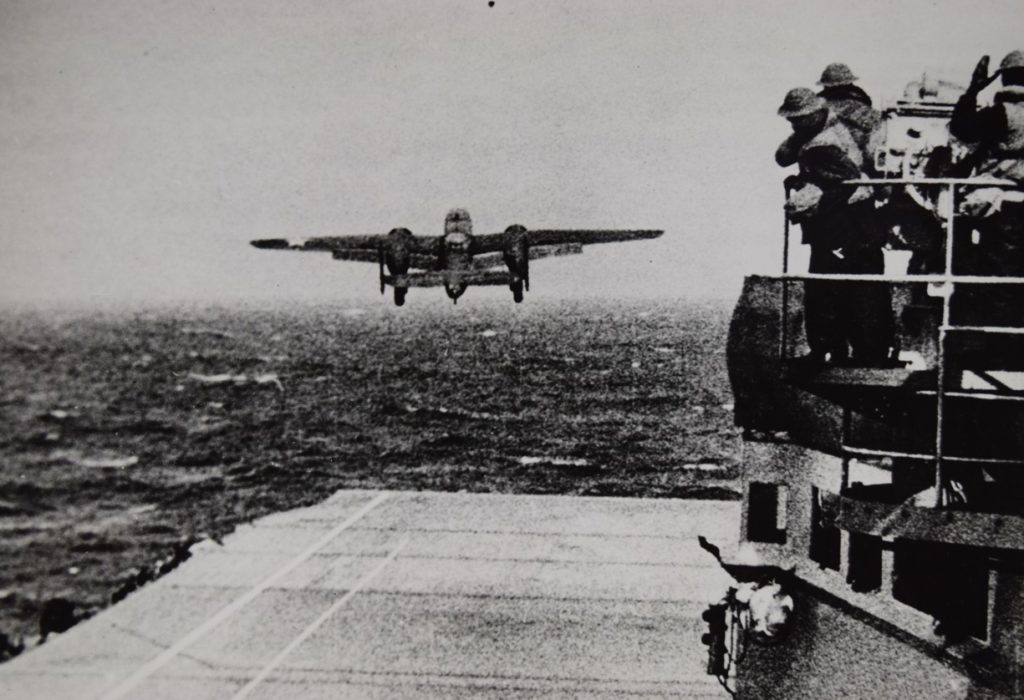

They had taken off from the aircraft carrier Hornet but were never intended to return there. Specially modified and overloaded with fuel in preparation for a too-long flight, they barely had enough runway on deck to take off. After flying 800 miles, most of it just feet above the waves to avoid detection, the 25 B-25s dropped bombs on the Japanese cities of Yokohama, Nagoya, and, above all, Tokyo.

This was the famous Doolittle Raid. Led by Lt. Col. James Doolittle, the attack had little strategic value in and of itself, but as a symbol, it demonstrated the United States’s ability to reach Japan. Just four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor nearly knocked the United States out of the war before it had even entered it, the Doolittle Raid was celebrated in headlines across the U.S., and for Japan, it foreshadowed much deadlier American bombing raids in the years ahead.

Clearly, the Doolittle Raid was a turning point in American and Japanese history, but its aftermath makes it a fitting topic for This Week in China’s History.

Even with their special modifications, the American bombers had no hope of returning to the Hornet; they were simply too far from their target. Instead, the plan was to continue west and aim for landing fields in “Free China”: territory controlled by Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) Nationalist government. Despite this plan, though, Chiang was kept out of the loop in the planning and execution of the mission. In part, this was because of the desire for secrecy to ensure the surprise that was essential to the raid, but Chiang was also opposed to the mission from the start, fearing (correctly) that Japanese reprisals would be both harsh and borne nearly entirely by China. Divisions within the American military contributed to problems as well: General Claire Lee Chennault, commanding the American air forces in China, might have been able to provide more accurate charts that would have helped the planes safely find an airstrip in China, but he was excluded from the final planning for the raid, not even sure it was happening until the planes had already taken off.

Given all this, hopes for success were, to say the least, based more on optimism than reality. When a chance encounter with a Japanese vessel compromised the mission’s secrecy, the planes launched 200 miles east of the original plan. There was no way that the bombers would be able to reach the Chinese landing fields. After successfully hitting their targets, all the planes — except one that turned north to Vladivostok — headed for China. Had it not been for a lucky tailwind, it is doubtful they would have even reached the Asian mainland. As it was, several ditched in the East China Sea just off the coast, but a dozen of them — 80 men — made it to China, crash-landing in Zhejiang and Jiangxi provinces.

Remarkably, of the 80 men who flew in the mission, all but three survived the crashes. For the others, their fate depended on where they landed and what they encountered on the ground. Some were captured by the Japanese; three of these were executed after a military tribunal. One died in prison. Five remained in Japanese custody until American forces arrived in August 1945. But unbelievably, the great majority of the raiders — 69 out of the 77 who landed in China — eluded capture and eventually made their way to safety, thanks to residents of Anhui, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang, who rescued, sheltered, and guided the American pilots.

And for this kindness, the Chinese paid dearly. As historian Rana Mitter put it in his book Forgotten Ally, “What went down well with the American public had a hugely negative effect on the Chinese war effort.” The Japanese brutally punished areas that had helped the American flyers. In all, 180,000 Japanese troops took part in an offensive — the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign — that was designed both to remove the threat of air raids against Japan from China and to punish the population for helping the Americans.

Foreign observers documented the Japanese vengeance, many of which were collected by historian James M. Scott in his book about the raid, Target Tokyo. In the village of Yihuang, American priest Wendelin Dunker wrote that the Japanese “shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved. They raped any woman from the ages of 10–65, and before burning the town they thoroughly looted it.”

The Japanese assigned collective responsibility to entire cities. The town of Nancheng, with a population of 50,000 people, was all but leveled for its role in sheltering American pilots, but anyone found to have directly aided the raiders was singled out for particular cruelty. Ma Englin, a resident of Yihuang who had sheltered an American pilot, was burned alive, his wife forced to set him alight.

In the words of Belgian-born priest Charles Meeus, “Little did the Doolittle men realize that those same little gifts which they gave their rescuers in grateful acknowledgement of their hospitality — parachutes, gloves, nickels, dimes, cigarette packages — would, a few weeks later, become the telltale evidence of their presence and lead to the torture and death of their friends!”

In all, approximately 250,000 Chinese were killed in the reprisal campaign, and some 20,000 square miles were laid waste. This embodies the central contradiction of the Doolittle Raid. It was at once a creative and ambitious tactic that influenced the course of the war in profound ways, but it also resulted in unspeakable cruelty against the populations that had helped the raiders return safely.

On the 80th anniversary of the raid, and with U.S.-China relations at low ebb, the complex, often contradictory legacy of the Doolittle Raid is more important than ever. I addressed this in my Royal Asiatic Society article about the raiders, “The Costs of Alliance”:

The Doolittle Raid sits at an uncomfortable intersection in history, one that has become even more complex in the eight decades since the mission. Despite ongoing tensions in the Sino-U.S. relationship, organizations in both China and the United States marked the 80th anniversary of the mission. Events included a virtual seminar organized and hosted by the Jiangxi Provincial Government and local historians. More than a dozen locations in the U.S. commemorated the anniversary. Could the legacy of the Doolittle Raid help serve as a catalyst for improved U.S.-China relations?

To be sure, this is a stretch, and yet the raid perhaps offers some faint hope: a moment of cooperation and friendship between Americans and Chinese that some on both sides seem willing to remember.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.