This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

What makes a work of art queer? Sometimes it’s a touch of camp, a nod to drag, an urge to turn convention on its head. Sometimes it’s a fiery voice, a call to storm the patriarchal prisonhouse of gender. Sometimes it’s a subtler note—a longing sigh, a wary glance, a pained admission of forbidden love.

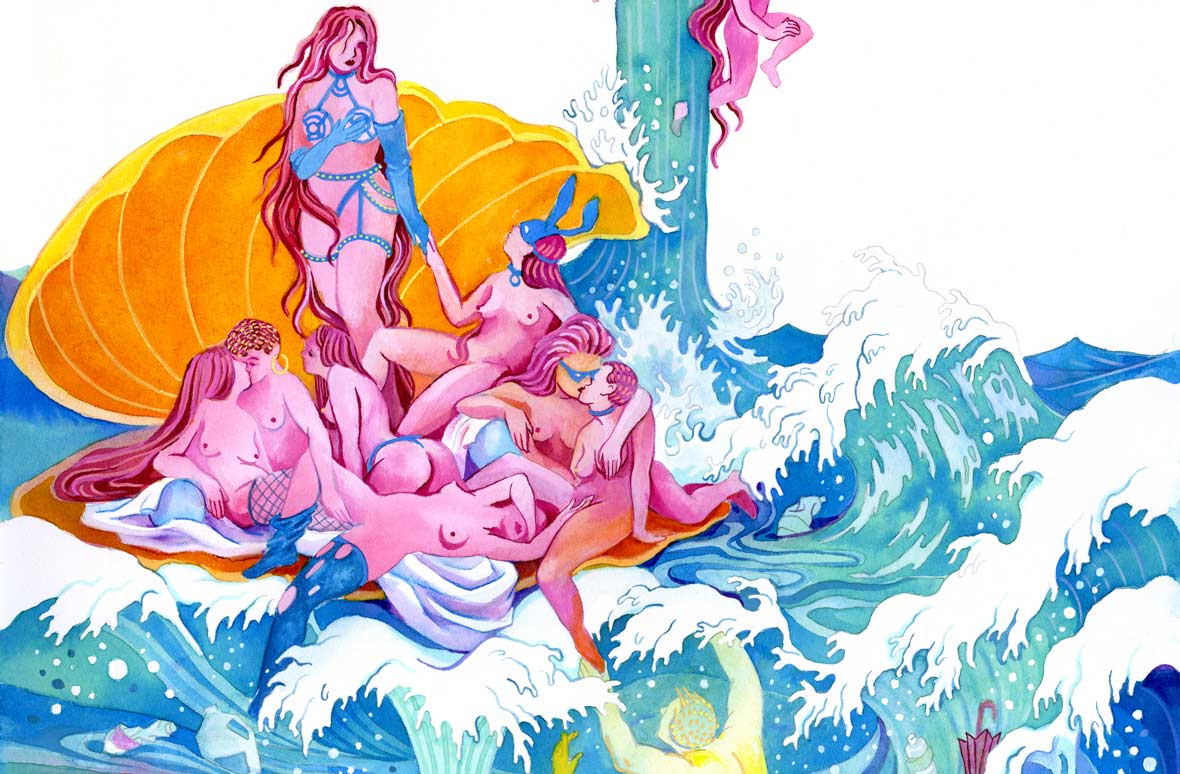

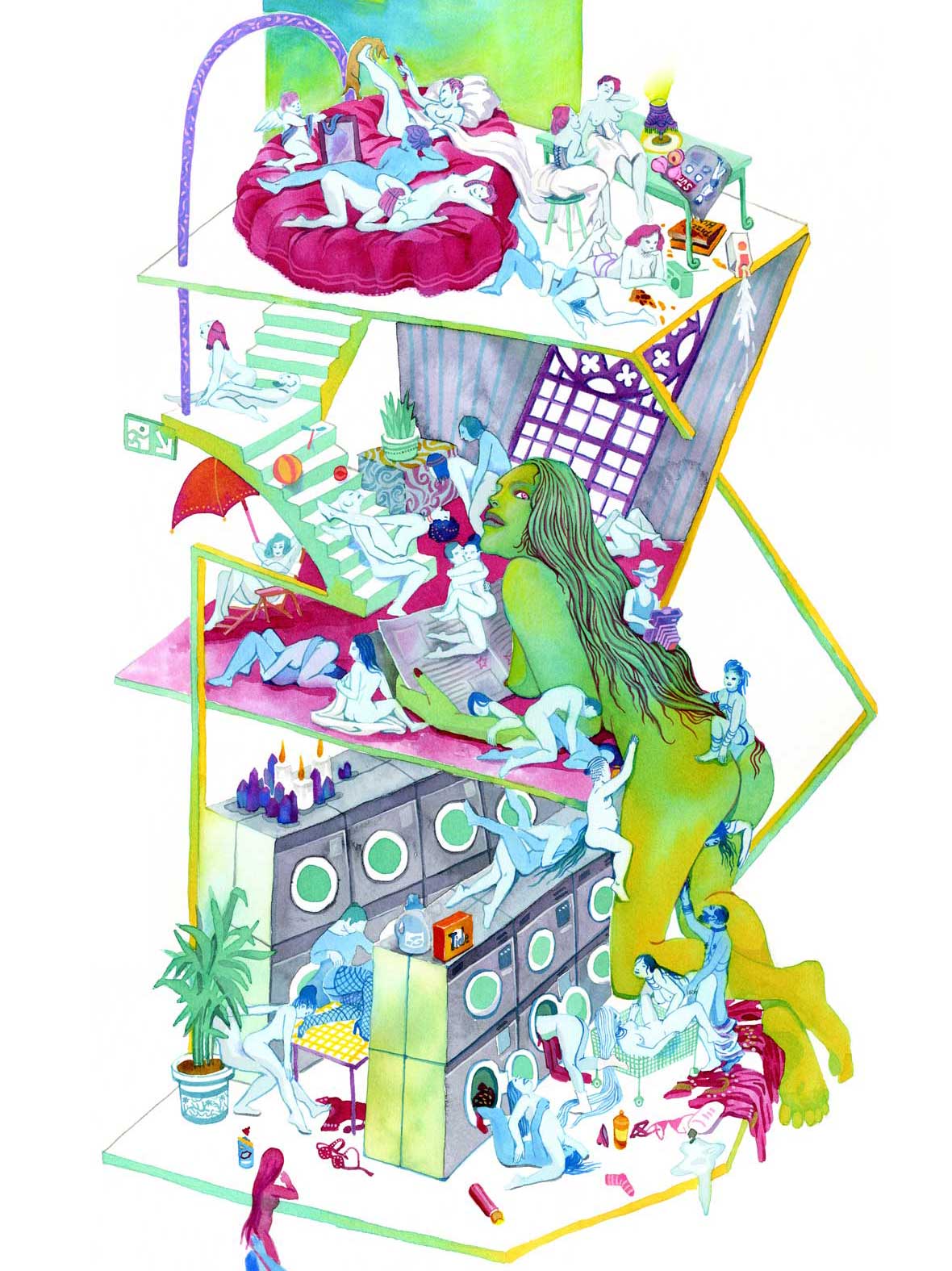

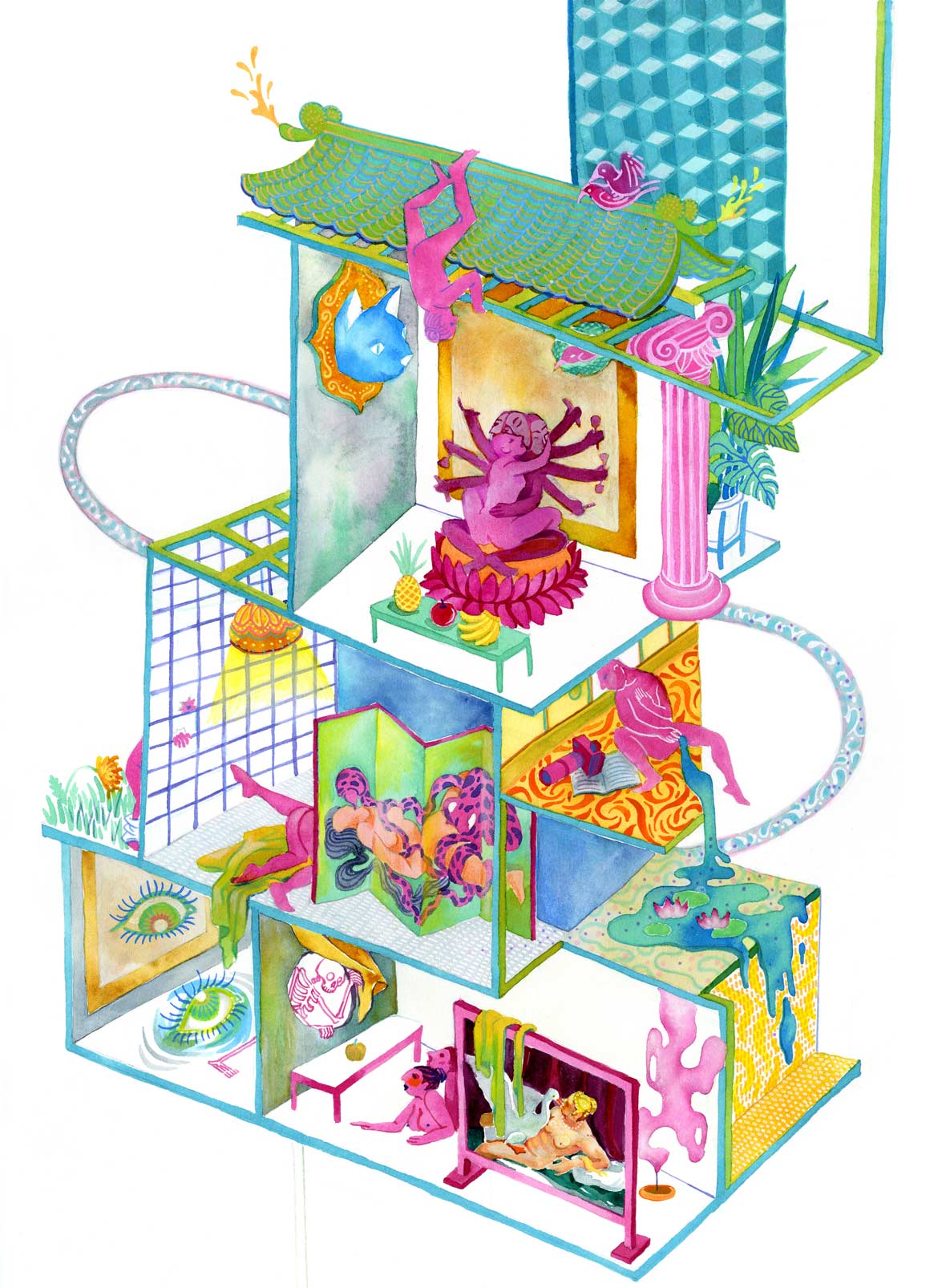

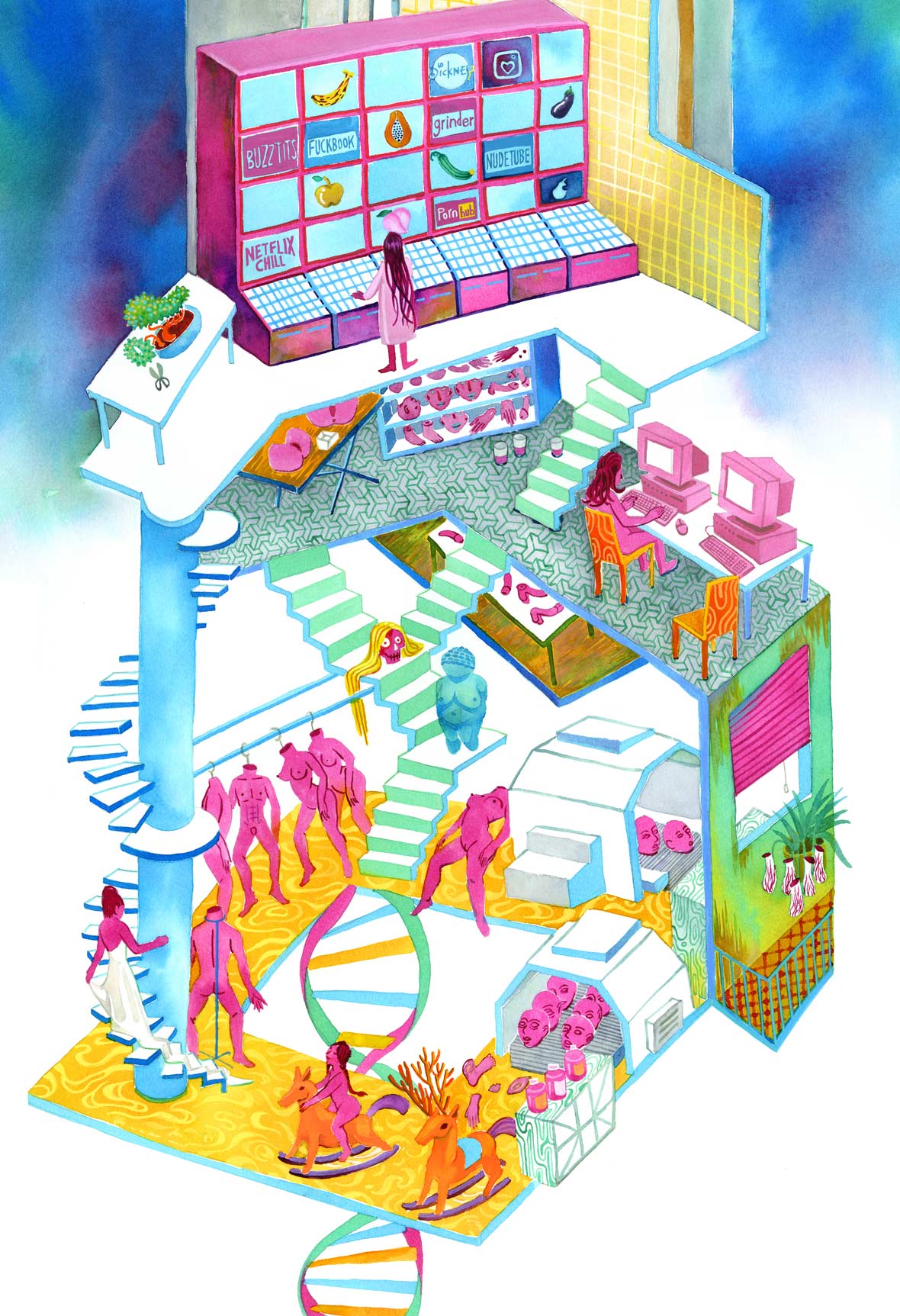

And sometimes it’s just rainbows and sex. Mǎ Huì 马慧’s work delights in every sort of erotic conjunction, with women and men and trans and nonbinary folk, in couples and singles and groups, all hugging, kissing, touching, rubbing, licking, romping, cavorting, frolicking, and fornicating their way across scene after libidinous scene. There are bodies of every description and shape and gender and hue—especially every hue: the rainbow colors seem to run together, like a pack of Skittles that’s melted onto the page.

“My subject matter is desire and sexuality,” says Ma. One of her series, Paradise Lust, with its throngs of undressed bodies, almost looks like an homage to Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights—or better yet, an X-rated version of Where’s Waldo? As in the Waldo books, here too the artist has hidden “Easter eggs” throughout each painting, and the curious and patient viewer can spot the Birth of Venus, the Girl with a Pearl Earring, and various Japanese Edo-period prints, along with the Pink Panther, Sailor Moon, and Captain Marvel. The sprawling, often physically impossible settings are as much a nod to M.C. Escher as they are to the perspectival conventions of traditional Chinese painting.

These titillating tableaux, these perverse panoramas, these—what shall we call them?—spectacles of salacity allow Ma to chart the breadth and variety of copulation. Bawdy as they are, they’re also strangely impersonal. Her figures are not individuals, but merely parts of a group, viewed from afar; in these paintings, the most intimate desires appear as a collective, almost abstract phenomenon. This effect is intentional, because in Ma’s view, sex links people across space and time. “I see sexuality not only as a personal experience, but also as a collective experience throughout history,” she explains. “The individuality fades in time, but the flesh, the experience, and the sensation are always there.” In Paradise Lust, she highlights the continuity of sex, rather than its subjective depth.

There’s also a political dimension to her choice. Instead of displaying, say, a single nude woman, like so many canonical works of Western art, Ma seeks to avoid the pitfalls of painting sexualized women, even as she celebrates a certain objectification. “I think it’s hard not to objectify the body you see,” she notes. And that being the case, why not make the objectification more universal, more democratic? “In my series, I depict not only female bodies, but also male bodies and even animals.” (Notably octopuses: in fact, in addition to the improbable and the impractical, the works contain a fair amount of the impossible and the unpalatable.) “I try to generalize the body form, and the fact that sex is enjoyable for all genders.”

Ma grew up in Beijing and now lives in New York, where’s she’s working on her MFA at the School of Visual Arts. Her international education lets her draw on techniques and influences from both China and the West. “I studied Chinese traditional painting when I was little,” she says. “The way that water and ink interact with rice paper still fascinates me. I love its immediacy, its abstractness, and especially how the brush strokes illustrate power and passion.” It’s also an ideal vehicle for her themes. “The water-based medium is perfect for depicting the sensation of fantasy.” Like watercolors, desire rarely stays within fixed lines.

Sexuality has been a topic of fascination since she was a child—mostly, she says, because no one talked about it. She recalls searching for information about sex from Chinese romantic novels, only to be surprised to discover, much later, that her own experiences were nothing like the ones she’d read about in books. A curiosity about the gap between desire and reality drives her art today.

“Paradise Lust is not entirely realistic,” she says, revealing a fondness for understatement. The setting seems to be a series of pleasure gardens whose occupants luxuriate among Greek columns, palm trees, and arches. According to Ma, though, the scenes take place not in some classical locus amœnus but on an eighteen-story rocket ship: each of the paintings in the series corresponds to a different level, as it charts its course to a pansexual Fire Island in the sky.

Otherworldly scenes like these may seem far removed from our terrestrial life, but Ma insists that fantasy can shape reality. For one thing, the variety of bodily entanglements suggests an equal variety of power dynamics. “The bedroom can be political too,” she says. “Who has the power in bed, who is taking charge? In a way, it defines the power dynamic in a couple. A queer woman could potentially break the gender binaries, and achieve equality in bed. Different positions give different kinds of pleasure without the necessity of defining who’s dominant.”

Blending the carnal and the carnivalesque, and folding in a strong dose of politics, Ma’s works are a celebration of desire in all its forms. They may not be realistic, but since when are desires confined to the limits of the possible? As that rocket blasts off, you almost wish you, too, could leave the earth behind for a while, and hitch a ride to Ma’s cosmic queer utopia.

To see the entire series as a single, unbroken image, click here.

Like this story? Follow neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Website: huimaillustration.com

Instagram: @notyourcockroach

Contributor: Allen Young

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li