This is book No. 16 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“The quotations also colored even commonplace exchanges, as described by one historian: ‘Serve the people. Comrade, could I have two pounds of pork, please?’”

—Tania Branigan, The Guardian

“Mao more than ever!”

—Bob Avakian, Chairman, Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

“During the Cultural Revolution owning it became a way of surviving.”

—Daniel Leese, professor of modern Chinese history and politics at the University of Freiburg, to the BBC

“Once Mao Tse-tung’s thought is grasped by the broad masses, it becomes a source of strength and a spiritual atom bomb of infinite power.”

—Lin Biao, foreword to the second edition of the Little Red Book

About the author:

Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, (1893-1976), also known as Chairman Mao and The Great Helmsman. Originally from a prosperous peasant family in Hunan, he was briefly a librarian in Beijing and an early member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1921. He participated in both the Jiangxi Soviet and the Long March and spent most of the war years in Yan’an. After 1949, throughout the chaotic years of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, he was the leader of the CCP and PRC until his death in 1976.

The book in 150 words:

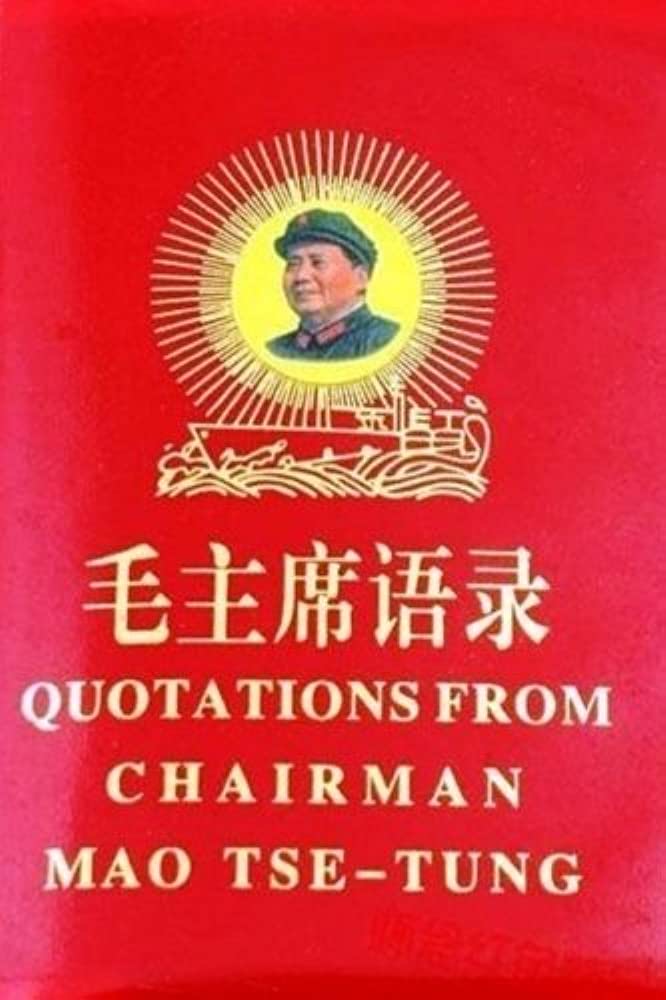

Formally titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, the Little Red Book is essentially, as Wikipedia succinctly puts it, “a book of statements from speeches and writings by Mao Zedong, the former Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, published from 1964 to about 1976 and widely distributed during the Cultural Revolution.” Except, of course, the book has become much more than that — a symbol, a talisman, an article of faith, a souvenir from China, a global rallying cry for revolution, liberation…change for some, the essence of rigid, uncompromising Maoism to others. It is the world’s second most published book, after the Bible. Reputedly a billion copies circulated in the Cultural Revolution, invariably covered in red plastic and shrunk to fit the pocket of an army uniform (or the back pocket of a Western radical student’s jeans).

Your free takeaways:

The Chinese Communist Party is the core of the Chinese Revolution, and its principles are based on Marxism-Leninism. Party criticism should be carried out within the Party.

Socialism must be developed in China, and the route toward such an end is a democratic revolution, which will enable socialist and communist consolidation over a length of time. It is also important to unite with the middle peasants, and educate them on the failings of capitalism.

U.S. Imperialism, European and Chinese reactionary forces, represent real dangers, and in this respect are like real tigers. However, because the goal of our Communism is just, and reactionary interests are self-centered and unjust, after struggle, they will be revealed to be much less dangerous than they were earlier perceived to be.

The mass line represents the creative and productive energies of the masses of the Chinese population, which are potentially inexhaustible. Party members should take their cue from the masses and reinterpret policy with respect to the benefit of the masses.

An army that is cherished and respected by the people, and vice versa, is a nearly invincible force. The army and the people must unite on the grounds of basic respect.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

A personal story. Growing up in London in the 1970s and ’80s, my mum and dad had a grand total of three books about China on their bookshelf. My mum had an old book club edition of Jan Maclure’s 1942 wartime adventure tale Escape to Chungking. My dad, a London history nut, had a copy of Chiang Yee’s The Silent Traveller in London from 1938, the exiled Chinese artist’s sketches and thoughts about 1930s life in the British capital. And there was a copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, the Little Red Book.

How had it appeared in our North London suburban house? Well, apparently my dad was working down in the old Port of London (now grandiosely redeveloped and known as “Docklands”). A PRC cargo ship docked, causing quite a consternation, as this was a rare event. A crowd, including my dad, gathered on the dockside to see the ship. Sailors gathered at the bow waving. Everyone waved back. One of the sailors appeared with a hessian bag full of copies of the vinyl-covered Little Red Book and the sailors began throwing them down to the assembled cockneys on shore. My dad snagged one, brought it home, and put it on his bookshelf. I have no idea if he ever read it.

That’s the thing about the Little Red Book, regardless of the worthiness or otherwise of the philosophical and ideological musings within. It went global; it went, as we might now say, viral. Ultimately the book is not overly important for its actual contents — mostly pithy but simplistic slogans with a veneer of Marxism-Leninism and little theoretical depth — but for the effect that holding and waving one had on China’s youthful zealots in the Red Guards and those around the world finding themselves drawn to Maoism. Later of course it became a piece of Maoist kitsch, a junkyard find, something picked up as a souvenir in a Beijing or Shanghai flea market, its pages never opened, just a bit more interesting than a toy panda or yet more tea.

The Little Red Book is inseparable from the history of the Cultural Revolution and the internal spats within the Chinese Communist Party, as well as from the less commonly remembered relationship between Mao and Lín Biāo 林彪, who had emerged as his heir apparent. A hero of the civil war who still held enormous sway with the People’s Liberation Army, Lin had helped create the cult of personality that had come to surround Mao; it was his orders in the early 1960s that newspapers should accompany editorials with an apt quotation from the Great Helmsman, which resulted in the compilation of his sayings into a bound collection that would become known as the Hóngbǎoshū 红宝书 — the Little Red Book. It was printed over one billion times during the first five years of the Cultural Revolution. Mao and Lin eventually fell out, with Lin dying in a mysterious plane crash over Inner Mongolia in 1971.

The book remains a primary symbol of the Cultural Revolution, part of the essential kit for Red Guards. Simon Leys (a Sinologist we will get to on the Ultimate Bookshelf before too long) visited China in 1972 and noted the Little Red Books as well as the posters, the paintings, the constant radio broadcasts, the aphorisms on the screen before movies started at the cinemas or plays, the music — to say nothing of Mao on the front page of all the newspapers every day, day after day. The sheer volume of Mao symbols was amazing — plates, mugs, bowls…his image was everywhere. The Little Red Book was everywhere, waved enthusiastically more than it was read closely perhaps, performatively recited more than it was pondered or discussed, a talisman that symbolized a creed and without which you ran great risks.

And now? Who owns, reads, even thinks about the Little Red Book? Curious students of China, the odd young person still drawn to Maoism (those devotees in West Bengal, Peru, and a few other spots globally), souvenir hunters in the Foreign Languages Bookstore, where a few fly-blown copies can usually be found? It’s no longer a talisman, but now a relic, a symbol of a not-quite forgotten but largely discarded period in China’s history. Waving a Little Red Book would probably get you looked at oddly in today’s China at best or, at worst, carted off to a police station and a hospital.

Next time:

Mao has come to overshadow just about every other major figure in Chinese communism, with the possible exception of the somewhat cozier figure of Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来. Those who early on flirted with anarchism (including the writer Bā Jīn 巴金) or Trotskyism (Chén Dúxiù 陈独秀, Wáng Fánxī 王凡西, etc.) have been effectively written out of Communist Party history. But the Party’s ideological legacy should not just be all Mao, all the time. One major figure in the Party, the one-time heir apparent, was, to international communist circles, at least the equal of Mao from the 1930s for several decades. He would also produce one of the major works of practical Marxist-Leninist ideology that is still read by revolutionaries around the world for its practical advice…

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.