Emotional storytelling and modernized folktales power a new era of Chinese animation

From exploring personal subjects to reimagining ancient stories in a contemporary context, a new generation of Chinese creatives are elevating the world of animation beyond its legacy.

This article is brought to you by Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, a leading international joint venture university based in Suzhou, Jiangsu, China.

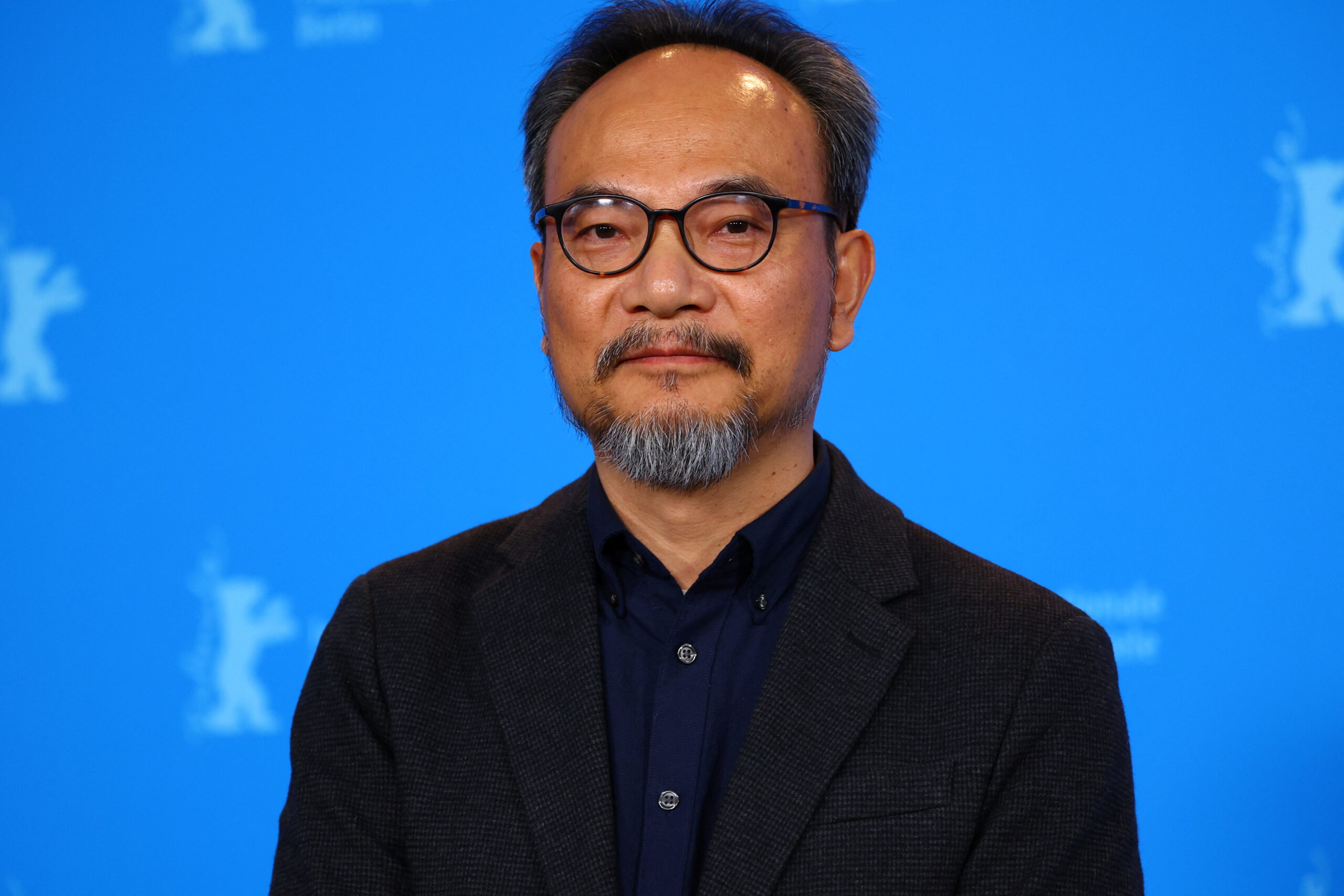

At the prestigious Berlin International Film Festival this year, some attendees got what might have been their first introduction to Chinese animation. Deep Sea, an experimental fantasy feature by writer-director Tián Xiǎopéng 田晓鹏, had its international premiere in the capital city of Germany, introducing a global audience to a dreamy underwater world full of life and color. Art College 1994, a unique 2D hand-drawn animated film by Chinese painter-turned-filmmaker Liú Jiàn 刘健, was selected for the Competition section, a rare feat for a Chinese movie, let alone an animated one.

The presence of Chinese animation at the Berlinale 2023 was so unprecedented and notable that iconic Japanese animator Makoto Shinkai — whose latest film, Suzume, was among the contenders for the Golden Bear at the festival — publicly voiced his excitement over the increased international visibility of Chinese animated titles.

“The quality of [Chinese] movies is improving rapidly, and they’re also able to build those unique characters that we have in Japan,” he was quoted as telling Agence France-Presse. “So I think that sooner or later they’re going to overtake us.”

Shinkai is not alone in recognizing that a new era for Chinese animation might be in the making. After years of stagnation, the Chinese animation industry seems to be experiencing what some tentatively call a revival, with a slew of films and series released this year earning accolades from both critics and regular viewers.

Leading this new crop of successful Chinese animated projects is Yao-Chinese Folktales, an online series that debuted in January and immediately became a cultural sensation that reached beyond core animation fans.

The anthology program, jointly produced by Chinese youth-oriented streaming site Bilibili and Shanghai Animation Film Studio, is a collection of eight fantastical stories revolving around creatures and figures from various folklore tales in ancient times and Chinese literary classics such as Journey to the West. However, rather than approaching the series with a fastidious loyalty to its source material, creators of the show retold the centuries-old stories in a way that was relevant and resonated with modern-day audiences.

Initially drawn to the series by its intriguing premise, Kelvin Ke, a filmmaker and an assistant professor in communication studies at the Department of Media and Communication at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU), says that he was pleasantly surprised by how well the program showcases the depth and scope of Chinese stories.

“I love the fact that each story reflects traditional culture and values and also shows the long history of Chinese culture,” Ke says. “In fact, I think that anyone who watches the series, especially Chinese viewers, would be struck by the fact that Chinese culture, folktales, and stories have so much potential and material for adaptations and animations.”

In one standout episode, “Goose Mountain,” a short novel about a peddler and a fox spirit, originally published during the Southern dynasties, is brought to life on screen, with its spooky undertone accentuated by a mesmerizing color scheme of black, white, gray, and red. In another popular installment shedding light on workplace issues in today’s China, a character from Journey to the West is portrayed as a burned-out subordinate struggling to meet his demanding leader’s unrealistic expectations.

These episodes particularly stand out to Zhonghao Chen, a lecturer at XJTLU Entrepreneur College (Taicang) and a prolific artist. “They not only present engaging micro-narratives and environment building but also showcase some truly innovative approaches to animation,” he says. “As a visual practitioner, I found the attention to and facilitation of the ‘surface’ of the animation to be particularly refreshing.”

“This ‘surface’ as co-creation of a beautifully crafted entanglement of both narrativity and visuality is a rare achievement today, given the industrialization of production and reproduction,” Chen further explains.

Beyond its creative storytelling, Yao-Chinese Folktales also utilizes a variety of artistic styles and techniques, including Chinese ink wash painting, pencil sketches, computer-generated imagery, and puppetry. It takes a team of dedicated individuals to bring the show to fruition, and the hard work has paid off. On Bilibili, the program has racked up more than 260 million views. On Chinese review website Douban, it currently has a score of 8.8 out of 10, an admirable rating for a homegrown production.

“I appreciated, in Yao-Chinese Folktales, the many references to certain important literary works in Chinese tradition and the originality of the standpoints, as well as the variety of styles and techniques, which reach outright eclecticism in some episodes,” says Dr. Marco Pellitteri, an associate professor in the Department of Media and Communication at XJTLU, whose work focuses on animation.

“The cultural mission of this mini-series is also to be appreciated and rewarded,” adds Dr. Pellitteri. “Amidst so much exaggerated and at times sloppy computer graphics in recent animations within and outside of China, Yao-Chinese Folktales is really a lot of fresh air, that is, I believe it is very innovative within the tradition of this glorious studio.”

Deep Sea is another Chinese animated production that received heaps of praise domestically. Set in a dreamlike, kaleidoscopic world of swirling color and cascading water, the film tells the story of a depressed young girl who embarks on an underwater adventure in search of an escape from reality.

Vividly realized in 3D animation and inspired by traditional Chinese watercolor painting, the film — created by the director of the 2015 animated blockbuster Monkey King: Hero Is Back and released in January — is visually stunning. And it doesn’t disappoint in its storytelling. Through its metaphorical discussion of mental health, the film also managed to strike a special emotional chord with its viewers, especially those grappling with depression, who praised the film for shining light on a somber subject that’s rarely highlighted or handled with compassion in Chinese media.

“Although most viewers would treat the film as just another animation, the truth is that it is a rather dark and challenging film about a young person searching for her place in the world as well as love, family, and home,” Ke says.

While similarly moved by the unusual theme explored in Deep Sea, Dr. Pellitteri believes the aesthetics of the film are too derivative of the work of Studio Ghibli, the iconic Japanese animation house that’s behind almost all movies by Hayao Miyazaki, including My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, and Spirited Away.

He adds, “Moreover, the film’s extremely emphatic deployment of computer graphics and special dynamic effects like morphing are something that, in my personal judgment, goes beyond animation. In fact, it pushes certain scenes to a domain of visual effects that is not so much the terrain of animation as an art, but rather a form of vertigo for the eyes. It has the noble intent to move the viewer’s emotions, yet the aesthetic result is, in my view, very artificial and unnecessary in some of the main, more spectacular scenes.”

But still, Dr. Pellitteri says that he has a special appreciation for Deep Sea’s effort to “push the previous boundaries of subjects in Chinese animated cinema” and its ability to initiate dialogues about current issues “through the lens of the fantastic, the dream, and the allegory.” As a result, “younger audiences and adult viewers can find a fertile ground for individual and collective reflection and growth,” he remarks.

While animation is chiefly associated with Japanese anime or major U.S. studios nowadays, China was once proud of its top-notch animation industry. When Havoc in Heaven, a two-part feature-length fantasy featuring the mischievous Sun Wukong, came out during the Mao era, it received numerous awards, as well as widespread domestic and international recognition. But after putting out a string of excellent works following Havoc in Heaven, the Chinese animation industry suffered a drought of creativity in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Although the last decade has seen a modest boom for Chinese animated productions, with films like Ne Zha and Monkey King: Hero Is Back finding success in the local box office, finding their voices on the global stage remained a challenge for Chinese animators.

However, this year, the upward trajectory of Chinese animation seemed to have finally pierced the international market. At the Berlinale 2023, Art College 1994, an animated portrait of youth set on the campus of the Chinese Southern Academy of Arts in the early 1990s, was included in the competition lineup, marking a new achievement for the Chinese animated film industry.

“It is rather rare for Chinese animation to make a splash overseas. So it is a good step forward,” Ke says. “I think that it is a fantastic thing for Chinese films, live-action and animated, to participate in any kind of international forum or film festivals. The reason is because I think there are a lot of misconceptions about China, Chinese people, and Chinese stories.”

Being on the international film festival circuit also allows “Chinese animated films to be perceived as part of the international community of artistic output in the world of animation,” Dr. Pellitteri says. “This could also entail that the new generation of Chinese animators — or at least the more talented ones — become part of a global growth in the aesthetics, technical know-how, and storytelling approaches, joining global joint ventures in an intercultural framework.”

For Chinese creatives to continue making strides in the animation sector, Dr. Pellitteri suggests artists keep exploring outside China’s wealth of cultural legacy or making it relevant in the current times.

“If Japanese animation teaches us something, it is that stories set in traditional historical settings or fantastic folktales cannot be the only kind of animation that should promote a national, recognizable production. They should be proposed together with stories set in current times, or in global scenarios, in ways in which what really stands out is the quality of the stories, the depth of the characters, and the incisiveness of the design and the moving images per se,” Dr. Pellitteri says, adding that “Chinese animation is on the right track to achieve all that both regionally and globally in the next decade or so.”

Echoing Dr. Pellitteri, Ke notes that although it’s likely that “animations with sweeping and epic stories will continue to dominate the industry,” he hopes that more Chinese animators will tell personal stories and tackle contemporary issues in their works. “The strength of Chinese animation right now is not necessarily technical ability. Rather, it is about emotional storytelling and Chinese stories. From a bigger picture, maybe stories can also try to reflect social and personal problems that are reflective of modern life in China,” Ke adds.

But will Shinkai’s prediction — that China will eventually overtake Japan in the animation sector — actually become a reality? Dr. Pellitteri says that the comment needs to be put in context.

“Mr. Shinkai, with his statements, was not only paying his sincere respects to the recent achievements of animation in China, but he was also speaking to his own stakeholders in Japan: The entire media ecosystem and the policy makers in Japan are not responding very organically to a variety of challenges in the framework of international competition in the field of animation,” Dr. Pellitteri says.

He also calls for a more complex understanding of what “overtake” means, as “it is not just a matter of talent or quantity of output, but also of capital deployed and assets created.” In Japan, there are already flows of Chinese capital and entirely Chinese-owned animation studios whose productions are branded as “Japanese anime.” However, for purists, that label would only apply to productions from Japanese studios, made by Japanese creators.

“These are exciting times for Asian animation, and I am very curious to see what will happen in this artistic and industrial competition between Japanese, Chinese, and Korean animations,” he adds.