A tribute to mothers

How do we pay homage to mothers who have lost a child? Lu Xun did so by publicizing their sacrifices.

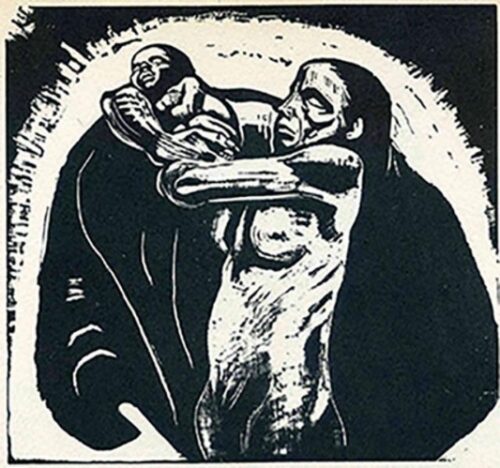

Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, pen name of Zhōu Shùrén 周树人 (1881-1936), arguably the most famous writer of 20th-century China, was particularly taken with the work of the German artist Käethe Kollwitz (1867-1945). Her woodblock print “Das Opfer” (The Sacrifice/The Victim) spoke to and for Lu Xun when he was grief-stricken after the death of a close friend. In “Remembrance for the Sake of Forgetting” (为了忘却的纪念 wèile wàngquè de jìniàn, 1933), he wrote about the Nationalist government’s execution of the leftist writer Róu Shí 柔石 (1902-1931). On hearing the news, Lu Xun wanted but found himself unable to write an essay commemorating his death. Knowing Rou Shi was devoted to his blind mother, Lu Xun published Kollwitz’s woodblock print “Das Opfer” in a journal, meant as a private tribute to Rou and his mother. But it was also a tribute to Kollwitz herself.

That Lu Xun would be moved by Kollwitz’s art is not surprising. In the late 1920s, Lu Xun became an avid collector and promoter of woodcut art. Inspired by European woodcuts, he sponsored workshops to train young artists in the craft, revitalizing a native art form in the process. His affinity with Kollwitz went beyond an appreciation of her work. Both had leftist sympathies, devoted their art to exposing injustice, and depicted the suffering of the poor and marginalized — grieving mothers among them. Kollwitz’s own story no doubt moved Lu Xun. In 1914, her youngest son died in the battlefield in World War I. “Das Opfer” was Kollwitz’s tribute to those dead from the war and the mothers they left behind.

Death, abandonment, and the unbearable grief of mothers had been recurrent themes in Lu Xun’s creative writings. His short story “Medicine” (药 yào, 1919) ends with two grieving mothers visiting the graves of their sons. One is the mother of the executed revolutionary Xia Yu; the other is Mrs. Hua, whose tubercular son dies after consuming a steamed bun dipped in Xia Yu’s blood — thought to be a medicinal cure for the child’s illness. Xià Yú 夏瑜 is a play on the name of the revolutionary martyr Qiū Jǐn 秋瑾 (1875-1907) — often referred to as China’s first modern feminist, Qiu left two young children behind when she was executed.

Another grieving mother appears in Lu Xun’s story “Blessings” (祝福 zhùfú, 1924). The traumatized Xianglin’s wife — name unknown, trafficked at least once, and widowed twice — recounts the tragic death of her child. Fascinated by her tale, the villagers initially flock to hear her story: Her missing boy had been carried off by a wolf and the body was later found in the wolf’s lair — the entrails had been eaten and his hand was still clutching a little basket. As they grow tired of the worn tale, however, some villagers shun her while others preempt and silence her by mockingly recounting parts of her story. Xianglin’s wife ends up a pariah wandering the streets as a beggar. As the villagers celebrate New Year’s day, she is found dead, possibly a suicide.

A powerful and more hopeful image of a grieving mother can be found in “Tremors on the Border of Degradation” (颓败线的颤动 tuíbài xiàn de chàndòng, 1925), an experimental short piece collected in Lu Xun’s Wild Grass (野草 yěcǎo). A mother prostitutes herself to raise her young child. The mother is later ostracized in old age by the same daughter for her shameful past. The old woman leaves the jeers behind her as she walks out of her daughter’s family home and into the wilderness at night. She stands stark naked in the wilderness, arms outstretched to the sky:

A language half-human half-beast, and not of this world and thus without words, flows from her lips. As she utters the wordless language, her entire body — like a once great and noble statue, now wasted and withered—trembles all over…she then raises her eyes to the sky, and her wordless language breaks off into complete silence. Only the trembling radiates outward like the rays of the sun, instantly whirling around the waves in the sky, like a hurricane billowing in the boundless desert.

Crystallized in the art of Lu Xun and Käethe Kollwitz are stories of injustice and loss. Revealed are the indignities suffered by mothers — some whose children are dead or estranged — and the resilience often required of them. In the gaps between art and reality, between the silence and the outcries, are powerful representations of inexpressible human grief that reverberate across time and space. Their art makes visible the hidden pains and wounds of mothers who have suffered unspeakable loss and pays tribute to them.