Beijing LGBT Center shutters after 15 years, citing uncontrollable factors

“I don't think the Center crossed a line, but rather the line crossed them.”

In a devastating blow to the queer community in China, the Beijing LGBT Center — one of the largest and last-standing organizations serving sexual and gender minorities in the country — has announced its shutdown after celebrating its 15th anniversary in February and surviving multiple waves of governmental clampdowns on LGBTQ spaces.

The abrupt announcement of disbandment was posted to the group’s official WeChat account this morning, only two days before the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOBIT), which commemorates the World Health Organization’s 1990 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder.

In the shocking post, the organization said that it had ceased all operations as of today, citing unidentified external factors out of its control. “Thank you for following and supporting us over the years,” the statement reads. “We kindly ask for your understanding for any inconvenience caused. We hope everything will work well for you in the future.”

The Center added that for people who had paid to attend its events, refunds would be processed by May 26. For those who had donated to the organization, they could request information about how their donations will be handled.

Founded in 2008, the Beijing-based organization was a prominent LGBTQ advocacy group that fought tirelessly for queer rights and provided a vibrant space for members of the community to connect. One of the group’s first achievements involved educating psychologists in China about conversion therapy, a dangerous practice that targets LGBTQ youth and seeks to change their sexual or gender identities. In 2014, the Center played a catalyzing role in launching China’s first LGBTQ impact litigation case, helping a gay man win a lawsuit against a practitioner of electroshock conversion therapy.

Despite tightening restrictions on queer activism in China over the years of its existence, the Center managed to spearhead a variety of influential initiatives, including organizing educational programs geared toward trans healthcare, setting up speed-dating events for queer people, and compiling information on LGBTQ-friendly clinics.

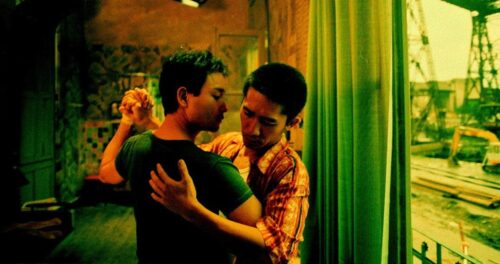

“The Center was so many things: a hub, a refuge, a flagship, a festival,” Darius Longarino, a research scholar at the Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai Center, who has worked extensively with experts in China seeking to advance LGBTQ rights, told The China Project. “They provided services to the community like mental health counseling and HIV testing and ran myriad activities like film screenings, exhibitions, English corners, parties, and discussion groups on coming out and intimacy — and so much more.”

“Over the years, countless people came through the Center to participate in its life and work in some way. They touched many lives and left beautiful memories,” he added.

Stephanie Yingyi Wang, an assistant professor of gender and sexuality studies at St. Lawrence University, told The China Project that the Center was special in that it provided “a regular physical meeting place for queer people” in the country.

“A lot of the past participants became volunteers and even staff,” Wang, who has worked with the organization on various initiatives, said. “Its closure is indicative of the dying of these kinds of community spaces for queer people in China, because the Center had been a beacon for many people, especially younger people in smaller cities and rural areas, to seek refuge.”

In a country where LGBTQ-related research is hard to conduct competently due to the sensitivity of the topic, the Center was able to work with forward-looking scholars and institutions to carry out large-scale surveys about the lives of queer individuals in China, such as a 2017 survey with Peking University on the mental health of transgender Chinese people. These reports, according to Longarino, “crucially filled an information void and have been continuously cited by journalists, activists, and academics.”

Although China decriminalized homosexuality in 1997, living in a truly accepting and inclusive society still remains a distant dream for the Chinese LGBTQ community. Same-sex marriage is yet to be recognized, and queer people still face discrimination and animosity in society. Meanwhile, groups advocating for LGBTQ rights have long had to deal with close scrutiny and routine crackdowns by the government.

As a result of China’s intensified effort to reduce the space for queer activism, ShanghaiPRIDE, one of the country’s longest-running and biggest festivals celebrating its LGBTQ movement, decided to stop all activities in 2020 to protect the safety of its people. A year later, Chinese social platform WeChat quietly deleted dozens of LGBTQ accounts run by university students, claiming that some had broken rules about publishing information on the internet. Later that year, in a similar fashion to how the Beijing LGBT Center revealed its closure, LGBT Rights Advocacy China, a nonprofit organization with a focus on changing law and policy concerning queer people in the country, suddenly announced in a WeChat post that it had shut down but did not disclose the exact reason.

To cope with the increasingly hostile environment, the Beijing LGBT Center appeared to have adopted a less progressive agenda in the past few years, shifting its focus from pushing for radical reforms to serving the community through initiatives like networking events, educational workshops about sexual health, and joint programs with large companies to increase workplace diversity and inclusion.

“The Center has been under constant scrutiny and surveillance for its work, but because it’s been in operation for a long time and had been actively negotiating with the authorities, it still managed to maintain its major programs. As I know, more and more of its activities were affected and forced to stop recently,” Wang said. “I can only say that this closure seems inevitable in the long run, but I still admire how long the Center has stood up against immense pressure and remained to be the beacon for many.”

Longarino said that a highlight of the Center’s recent work was its campaign to promote LGBT-affirming mental health care, which was pivotal given that one-third of mental health professionals in China still believed being gay was a mental disorder and that conversion therapy was effective, according to a survey the Center conducted with a scholar at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

“At the grassroots level, the Center organized dozens of training sessions for mental health counselors, sometimes with just a handful of attendees, to help them learn how to better serve their LGBT clients,” said Longarino, who has worked with the organization on some of these efforts. “Through slow and painstaking work, this became a network of thousands of LGBT-affirming counselors who then provided platforms from which the Center could reach higher-level stakeholders.”

On Weibo, the news of its sudden shutdown has triggered an outpouring of sadness and reminiscences about its importance to the community. “Ten years ago when I just graduated from school, I achieved self-acceptance here. Thank you and I hope future generations of sexual and gender minorities can still find their organization,” a longtime fan wrote on the Center’s Weibo page. “We don’t say goodbye. We say ‘See you down the road,’” a Weibo user who used to volunteer at the Center commented.

As the public space for civil society continues to shrink in China, the Center’s closure is an indication that “what was once accepted or tolerated no longer is,” Longarino said.

“I don’t think the Center crossed a line, but rather the line crossed them,” he added. “Media used to be able to report on LGBTQ-related rights litigation and there was more space for discussion and expression. Now, with the suppression of these voices, those pushing stigma and prejudice have become more dominant.”