This Week in China’s History: May 16, 1938

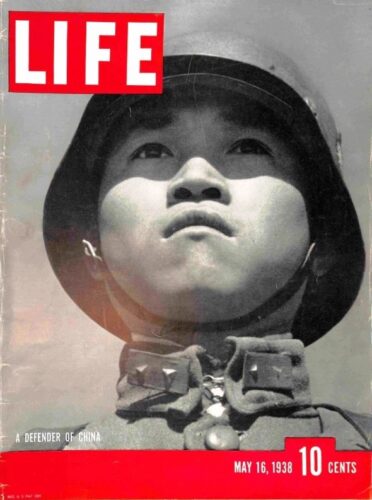

On May 16, 1938, readers in the United States could find on the cover of Life magazine — the most-read periodical in the country — a photograph of a Chinese soldier staring into a clear sky behind the title “A Defender of China.”

The photo, and the issue’s contents, had several purposes. One was to report the news of Japan’s invasion of China and the expanding Pacific War, which had begun nearly a year earlier. The second was to rally American support for China and prepare public opinion for American involvement in the war, which would of course become a reality late in 1941.

But perhaps the most enduring legacy of this issue was the publication of “ten grainy black-and-white images, printed in small format — almost requiring the reader to stare closely at the page to make out the details,” as historian Joseph Ho describes them in his book Developing Mission. “Several close-ups of burned, stabbed, and mutilated bodies, mostly produced in hospital settings and showing graphic wounds, appeared next to images of decaying corpses spread across a city street and floating in canals.”

These were the first images to reach the global public of the atrocities that came to be known as the Rape of Nanking, when Japanese troops murdered, raped, and brutalized civilians when they occupied Nanjing. Although the images were credited anonymously to protect their source, they were stills from 16mm movie films taken by American Episcopal missionary John Magee, who was at the time still living in Nanjing and part of a multinational group of missionaries, businesspeople, and educators maintaining a refuge in the city’s center, negotiated with the Japanese occupiers, called the Nanking Safety Zone.

Japanese armies advanced into Nanjing on December 13, 1937. Most of the city’s defenders fled along with the Chinese government, which eventually established itself at the wartime capital in Chongqing. For the next six weeks, Japanese soldiers acted without restraint against Chinese civilians, sometimes under the pretext of seeking to capture Chinese soldiers who had shed their uniforms to conceal their identity, but generally. without any need for justification.

The Tokyo War Crimes Trial — officially the International Military Tribunal for the Far East — concluded that the Japanese Imperial Army killed some 200,000 people during those six weeks, although estimates range widely. Tens of thousands of women were raped.

Rumors of what was happening in Nanjing spread quickly. The English-language press in Shanghai published reports on an “orgy of looting, murder, and rape that took place following the entrance of Japanese soldiers” into Nanjing, and similar stories appeared in newspapers around the world.

But although the news about Nanjing was not a revelation, the images of atrocities carry a power that words struggle to match. Japan had been working hard to suppress and manage images of its war in China since the summer of 1937, and blamed images like H.S. Wong’s photograph of an injured, crying baby sitting amid the flaming ruins of Shanghai that appeared on the cover of Life in October.

Joseph Ho documents how Japanese military authorities confiscated the (mainly) American missionaries’ film, cameras, and other equipment, and carefully monitored their actions. Not only that, but Japanese forces staged photo opportunities for Japanese and international reporters, including Japanese soldiers distributing candy and providing medical care to children.

Observers on the ground knew better. Minnie Vautrin, the American president of Ginling Women’s College, protested daily at the Japanese embassy that Japanese soldiers were appearing daily at the school to kidnap women who were sheltered there. “There probably is no crime that has not been committed in this city today,” she recorded in her diary. Described in her biography by Hua-ling Hu, “Thirty girls were taken from language school last night, and today I have heard scores of heartbreaking stories of girls who were taken from their homes last night — one of the girls was but 12 years old.” George Fitch, another American missionary, described the situation in his diary (reproduced in the book Eyewitnesses to Massacre, edited by Zhang Kaiyuan) as “hell on earth” with “no parallel in modern history,” as “thousands of disarmed soldiers who had sought sanctuary with you together with many hundreds of innocent civilians are taken out before your eyes to be shot or used for bayonet practice.”

John Magee’s films were taken inside the Safety Zone’s hospital, though some footage was shot through windows of scenes outside. Though the stills published in Life were graphic and horrifying, they could not compare to the motion picture footage — eight reels’ worth — that captured the brutality in Nanjing. As Ho describes them, Magee’s films “do not simply rehash pre-existing narratives about medical missions and humanitarian care. Rather, they re-contextualize them, with broken bodies and images of treatment pointing to the military brutalities that caused the grotesque wounds and deaths.” Magee filmed grim scenes of bodies, wounded and killed, but added to them a narrative explaining how, through interviews, he had learned what had led to the deaths and mutilations. How it was, for instance, that “16 and 14 year old girls, each lying in a group of people slain at the same time,” had met their fates. “Magee not only filmed the survivors and victims of the killings but also interacted directly with the subjects of his film to collect as many eyewitness details and additional footage as possible.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

The images that John Magee had filmed were important, not only to show the world what was going on, but to contradict the official story of the Japanese army. But the film needed to find a way out of Nanjing.

Fitch found the solution, arranging to be summoned to Shanghai on official business. Boarding a Japanese military train early on a January morning, Fitch wrote in his diary, “I was crowded in with about as unsavory a crowd of soldiers as one could imagine in a third class coach, a bit nervous because sewed into the lining of my camel’s-hair great coat were eight reals of 16mm negative movie film of atrocity cases.”

The films were soon shown throughout Shanghai (and even in Tokyo) as well as the United States. But the effect that Fitch and Magee hoped to achieve did not materialize. After more than a year of showing the films publicly, Fitch grew tired and frustrated at the lack of public response. Ho writes, “Even when confronted with such graphic footage, U.S. audiences were still grappling with the question of whether the United States should continue its nonintervention and isolation, [and] Nanjing was soon, in the eyes of many observers, just one of several major cities to fall to the Japanese.”

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but the case of John Magee’s movies illustrate that they do not speak for themselves.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.