The first cross-strait dispute: How the Koxinga-Qing conflict informs modern Taiwan politics

Debates about cross-strait relations tend to focus on recent history, ignoring profound cultural and historical sensitivities that underpin this complex relationship. Take the story of Koxinga, a 17th-century merchant-pirate who in modern times has been co-opted by both Beijing and Taipei.

Two months ago, Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén), touched down in California to meet U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — prompting an all-too-predictable response from Beijing, a set of military exercises and threats toward the Taiwanese government. When it comes to cross-strait relations, these tit-for-tats have been going on for decades, stretching way back — not just to 1949, when Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) Nationalists fled to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War, but centuries further.

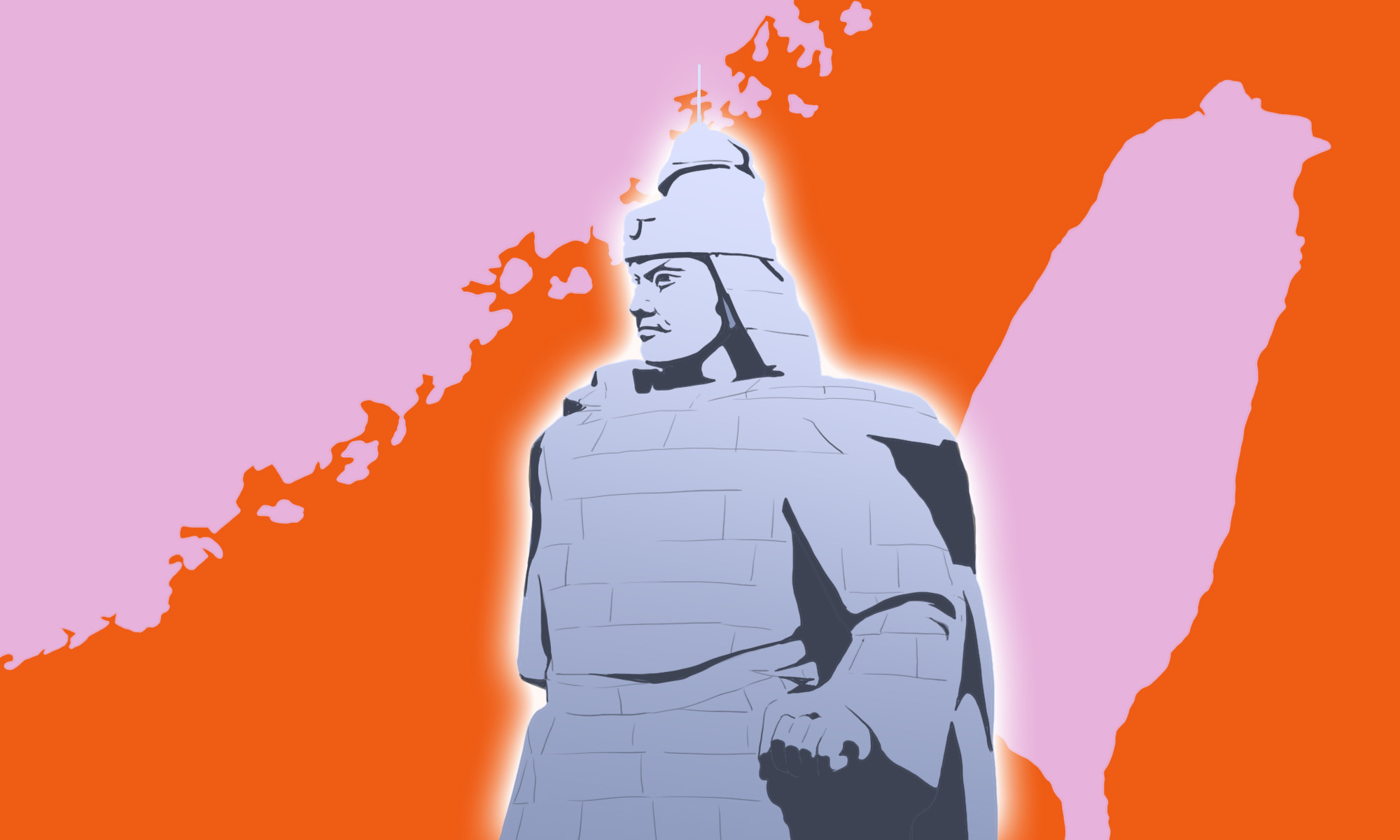

To find the first cross-strait dispute, we have to go to the 17th century, when a merchant-pirate named Koxinga fought against the Qing over the control of Taiwan. Understanding the historical context of this conflict might bring nuance to how we view contemporary cross-strait issues.

Also, it’s a good story.

It happened during the Ming-to-Qing transition period and is closely intertwined with the rise of merchant-pirates in China’s southern coast, specifically Fujian and Guangdong provinces. Its primary actors include the Ming and Qing authorities, influential coastal families, local fishermen, and Dutch colonists.

Zhèng Chénggōng 郑成功, known as Koxinga internationally, was a Ming loyalist and military commander who established a base on Taiwan to continue his campaign against the Qing after failing to capture Nanjing. His father, Zhèng Zhīlóng 郑芝龙, was a Fujianese merchant-pirate whose authority over the local seas was such that all merchants passing through needed his approval. During this time, natural disasters constantly threatened famine, and the elder Zheng cultivated respect from the poor through Robin Hood-esque extortion that provided jobs and nourishment to the peasantry. After sparring with the declining Ming, he offered fealty, which the Ming readily accepted to stabilize the strategic southern coast.

When the Qing rose to power, Zheng offered the same fealty, but this time, he was executed. Pandora’s Box reopened in the region, and Zheng’s son, Koxinga, took advantage of the turmoil to champion Ming loyalism and tighten his grip over shipping in Southeast Asia. After failing to take Nanjing, Koxinga fled to Taiwan in 1661, expelled the Dutch colonists, developed Taiwan’s industries, and laid the groundwork for two decades of anti-Qing resistance, ruling as the Kingdom of Tungning. By the time the Qing finally defeated Ming loyalists in Taiwan in 1684, the Qing’s Kangxi Emperor recognized the strategic importance of stability and prosperity in the South China coast and reversed decades-long restrictions on maritime trade.

There are some differences to note before making further comparisons between then and now: Koxinga and his descendants did not regard Taiwan as their independent territory and never intentionally tried to foster a unique Taiwanese identity. Instead, their focus remained on Fujian. And Koxinga’s pirate empire was one of several targeted by the Qing. Still, his legacy has been co-opted by both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and major political parties in Taiwan. For the former, he represents the successful struggle against Western imperialism. For the latter, he became synonymous with defending Taiwan against China’s aggression.

The Koxinga-Qing dispute, often referenced in Chinese and Taiwanese literature but overlooked in Western discussions, highlights Taiwan’s strategic role in East Asia and the formation of political identities under Koxinga and the Qing. It provides key insights into the historical complexities shaping current cross-strait relations.

China’s historical perspective on Taiwan

Like the Qing, the CCP views Taiwan as a vital part of China’s unfulfilled whole, essential for stability.

From this perspective, the Koxinga-Qing dispute highlights Taiwan’s historical connection with China, while also acknowledging the regional power dynamics and cultural diversity.

In this narrative, the Dutch colonization of Taiwan plays a key role. Koxinga’s triumphant reclamation of Taiwan from the Dutch East India Company is applauded, symbolizing resistance against Western imperialism and enhancing his status as a national icon. This storyline showcases China’s defiance against Western interference. Koxinga’s bold challenge against Western powers, his adept strategies, and his ultimate success represent a significant benchmark for the Chinese.

After the Qing’s victory over Koxinga’s descendants, the Chinese interpretation notes Taiwan’s incorporation into the Qing Empire. This relationship is central to the Chinese government’s “One China” policy, which considers Taiwan an inseparable part of its sovereign territory. Moreover, the Chinese interpretation emphasizes Taiwan’s political and cultural integration with the mainland during the Qing administration. Taiwan’s absorption into modern China is credited to the Qing’s economic, infrastructural, and governance development.

The formation of Taiwan’s distinct identity

In Taiwan’s historical narrative, Koxinga’s successful expulsion of the Dutch marked the beginning of Taiwan’s political and cultural development as separate from China’s. His mixed heritage and opposition to external domination make him a symbol of resistance.

His rule is seen as laying the groundwork for the island’s distinct trajectory. For instance, Koxinga’s administration fostered agricultural advancements, trade, and cultural exchanges with neighbors — including Japan — illustrating Taiwan’s early, independent trajectory. The Qing’s governance further contributed to the formation of a unique Taiwanese identity through its relatively hands-off approach to local customs. By permitting some Taiwanese autonomy, the Qing inadvertently nurtured cultural diversity and local agency. Taiwan cites this event to further its claim to autonomy.

But it’s important to note that the island’s two major political parties, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Kuomintang (KMT), interpret the Koxinga-Qing dispute differently. The DPP emphasizes Koxinga’s role in establishing the island’s identity and fostering resistance against external control. This interpretation aligns with the party’s pursuit of self-determination in the face of China’s assertiveness. On the other hand, the KMT, which supports eventual reunification with China under the “One China” principle, acknowledges the historical connection between Taiwan and China during the Koxinga-Qing dispute. It points to the cooperation between Koxinga’s regime and the Ming loyalists in China. However, the KMT also recognizes the unique political and cultural developments that occurred in Taiwan during this period, including the importance of preserving its distinct identity.

Koxinga’s mixed Chinese-Japanese heritage and the trade relationships he established have also shaped Taiwan’s perspective on Japan. Koxinga is seen as a bridge between Chinese and Japanese cultures, fostering a sense of affinity between Taiwan and Japan. Although many Western observers discuss Taiwan’s economic development during Japanese colonial rule, the Koxinga-Qing dispute set the precedent for the island’s contemporary diplomatic and economic relations with Japan.

Implications on modern cross-strait tensions and lessons for diplomacy

The Qing imposed draconian restrictions, such as sea bans in 1652 and forced inland evacuation in 1661, hoping to quash Koxinga. Instead, this turned displaced locals and fishermen into rebels, fueling anti-Qing activity in southern China. This lesson suggests that attempts to isolate Taiwan today might only heighten anti-China sentiments. Fostering cross-strait communication and connections is a crucial diplomatic goal.

Additionally, the significance of trade is underscored by the Qing’s disruption of China’s commerce, leading to its diversion to Taiwan, Macau, Japan, and other Asian ports. This highlights the need for regional interdependence, advocating for diversified industries in Taiwan and stronger economic ties with China, particularly through intermediaries like the Taishang. This balanced strategy could temper economic pressures and stabilize regional politics.

Drawing from the rich tapestry of historical narratives, Koxinga’s resistance and the Qing’s policies serve as more than mere stories from the past. History shows us the importance of open communication and trade. By grasping these narratives, the West can navigate current cross-strait complexities with a more nuanced and informed diplomacy.

All views expressed here are those of the authors alone and not of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.