Epic and ordinary: Shang Zhefeng’s photographs tell the story of China’s majority

In the work of millennial photographer Shang Zhefeng, personal stories of China’s working class are told through the lens of their unique surroundings. "The environment I grew up in inspires what I do," Shang says. "Coming from a lower social class, I represent the majority."

Venturing into his hometown in rural Shaanxi to investigate his roots, Shanghai-based photographer Shàng Zhéfēng 尚哲峰 opened Pandora’s box. He realized the story he was tracing was not only his own, but also that of a majority of people in China. In addition, he came to some unsettling conclusions about the social system he grew up in and the issues that remained. His epiphany resulted in three photo series: Cypress Slopes, My Time, and Theater Stage. Combined with his earlier Shanghai Scenery, they form a poignant portrayal of life in China spanning 100 years.

Shang’s work starts with his own background and then expands to encompass the struggles of the broader working class. “The environment I grew up in inspires what I do. Coming from a lower social class, I represent the majority,” he says.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Born in 1991, Shang grew up in the small village of Baishupo, present-day Dongfeng. His father still works as a builder; his mother held several jobs throughout her life and now contributes to the family income by growing pepper in their backyard. When Shang graduated from high school at age 17, they arranged for him to study graphic design at a vocational school. “Kids born in the countryside like me only had two choices: learn a skill or find work straight away,” he says.

Shang’s first significant contact with photography was working as a retoucher at a local studio in his hometown. Years later, in 2015, he began experimenting with the medium, inspired by the works of celebrated Japanese photographers Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama, and Tadahiko Hayashi.

“Their work was not only beautiful, but it also touched me inside,” he says. “These were my most lonely times, and photography became an outlet to express myself and convey my thoughts.”

Shanghai Scenery was Shang’s debut, a powerful photographic series that depicts the colossal scale of urban development taking place in one of China’s fastest-growing cities. By capturing the processes of demolition and construction, the project explores a rapidly transforming Chinese landscape and examines how it affects the lives of ordinary people. Shang himself is featured in many shots, sometimes inside abandoned rooms, facing the camera with a clicker in hand, surrounded by the objects people left behind.

Shooting this series involved a fair bit of urban exploration. Shang had to trespass restricted construction sites and wait inside derelict buildings long enough for light conditions to change. “I learned to endure loneliness and wait patiently for the clouds to cover the sun in each shot. This series solidified my commitment to photography and helped me take a direction for my work that considers factors specific to the common people of China,” he says. “In a way, it also helped me to find my position within the city. I thought there were similarities between those demolished buildings and how I felt.”

Shang began working on Cypress Slopes in 2019 when he visited his family to celebrate Chinese New Year. In late 2020, following an impetus to gain insights into his identity, he continued the project with a renewed interest. The series, whose title is the English translation of Baishupo (柏树坡 Bǎishùpō), combines photographs of the local landscape and residents with images of found objects and documents.

“[The latter] can be old photographs I bought on flea markets or online, scenes from my hometown captured decades ago in old videotapes, fragments of porcelain and mud jars I found scattered on the slopes of the village, receipts, land deeds, weaving shuttles, and even clay sculptures I made myself,” he says. “I also delved into my childhood memories, flipping through old family photo albums and my grandfather’s land deeds, which I had collected when I was young,” he adds.

While rummaging through the home, Shang found documents such as work allocation records dating back to the collectivization period and letters that revealed much about the struggles of his ancestors and the profound social changes they had to endure. He also had long conversations with his great-uncle to trace his heritage back four generations, or roughly 100 years.

One interesting finding was the existence of a key figure who guaranteed the family’s succession: his great-grandfather’s wet nurse. “To me, her character is truly remarkable. She had no blood relation with my great-grandfather but became like a mother to him. He, in turn, took on the responsibility of continuing the family and rooted himself in Baishupo,” Shang says. “The times they lived through were hard, but also showed the brightest side of humanity.”

By talking to other senior citizens in the village, Shang learned much about life in Baishupo, including some humorous anecdotes. “They told me about this tradition that existed among the children of deceased elders: On the day of the funeral, whoever carried a fire basin on their head was entitled to inherit the deceased’s home. However, there was once a case where someone snatched the fire basin, leading to a long dispute over the division of inheritance,” he says, laughing. Shang has collected the document that arose from the dispute, an item he treasures dearly.

To him, one of the most memorable moments of working on Cypress Slopes was making copies of an epitaph he found on a road ditch stone. He had to work amidst strong winds and heavy rain while relying on his mother’s resourcefulness to create an impromptu tent. Overall, “this series was not so much an emotional journey as it was an archaeological expedition, a study on the times our ancestors lived,” he says.

Interestingly, as he presents the series to audiences, Shang doesn’t make any distinctions between the photographs and artifacts associated with his family and those of other families. He intertwines the fragments of various individual lives into a single and coherent portrayal to create a prototypical narrative that helps his generation understand what kind of life their ancestors lived.

In his quest to source material for Cypress Slopes, he stumbled across something inevitable: remarkable visual records of the Cultural Revolution. As fate would have it, all this research happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when China’s domestic policies tightened to levels not yet witnessed for at least a generation. Straight away, Shang identified unsettling parallels between the two eras in modern China’s industry regarding authority and arbitrary rules.

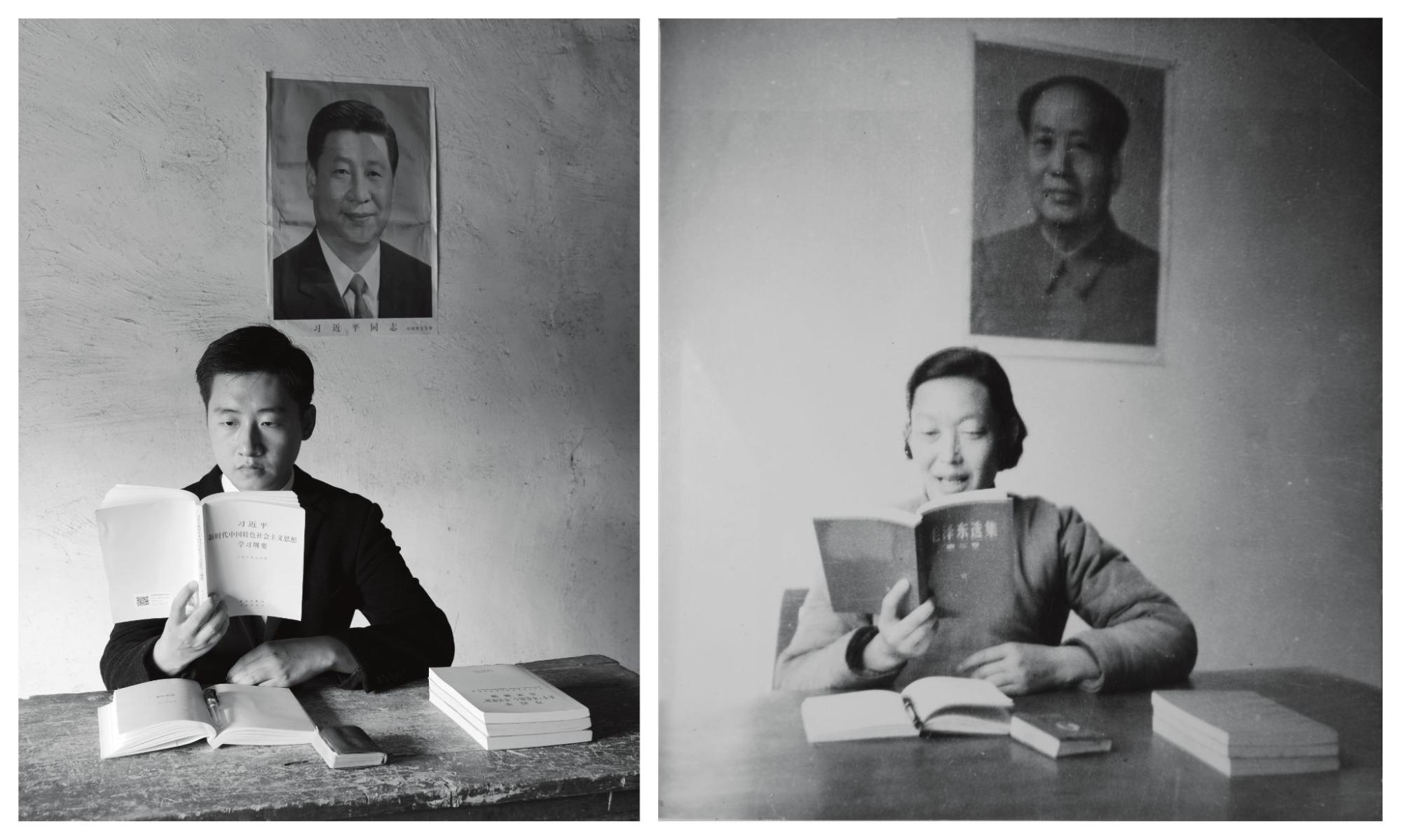

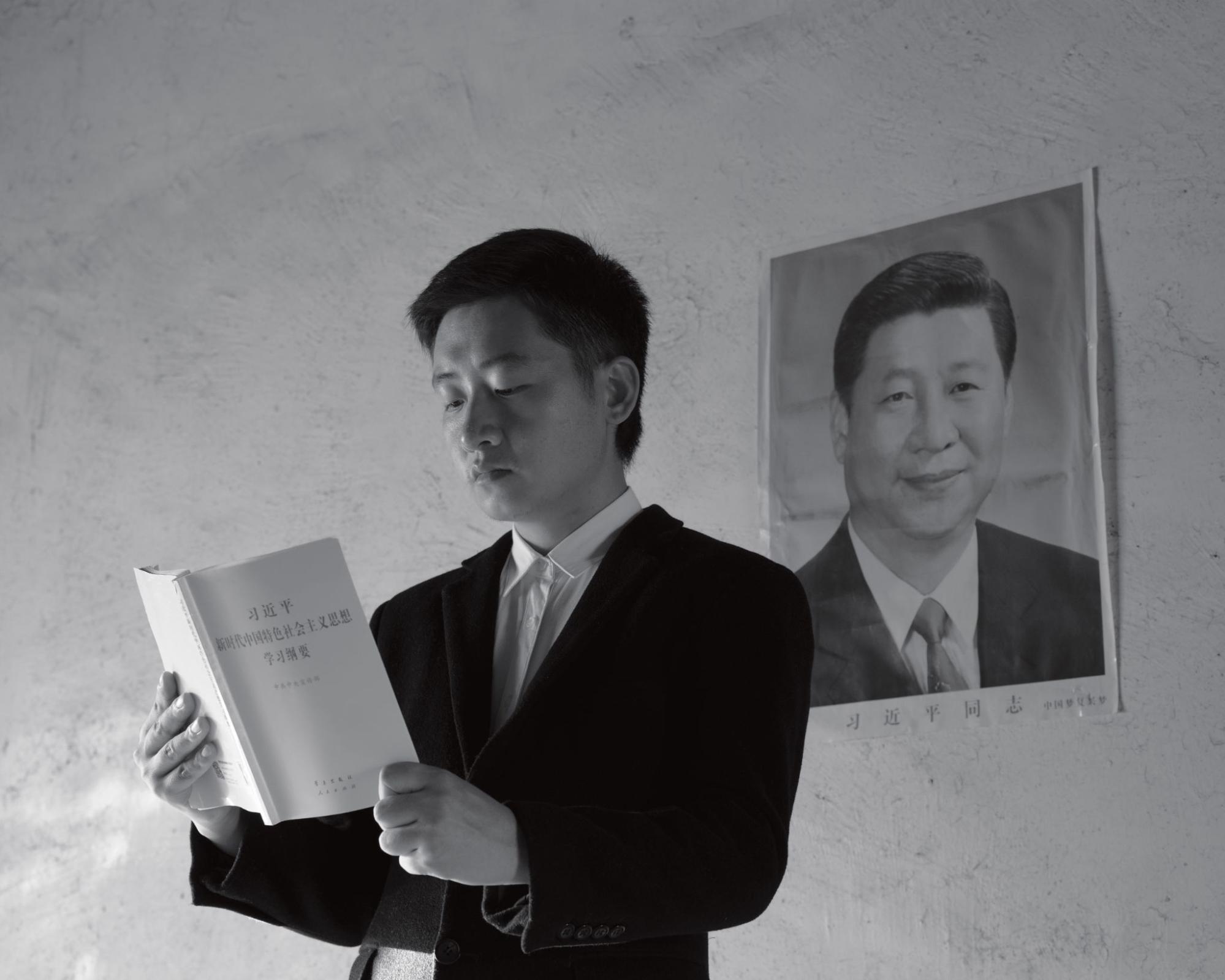

One photo, in particular, stood out to him: a young woman sitting on a teacher’s desk, reciting from a book of works by Máo Zédōng毛泽东, with his profile picture hanging over her. “I was already contemplating a new series based on these similarities, but when I saw this image, all my ideas came together,” Shang says.

This is the origin story of My Time, a collection of photomontages that shed light on systemic issues that remained from China’s troubling past, things that have become even more evident because of the COVID-zero policy and its side effects.

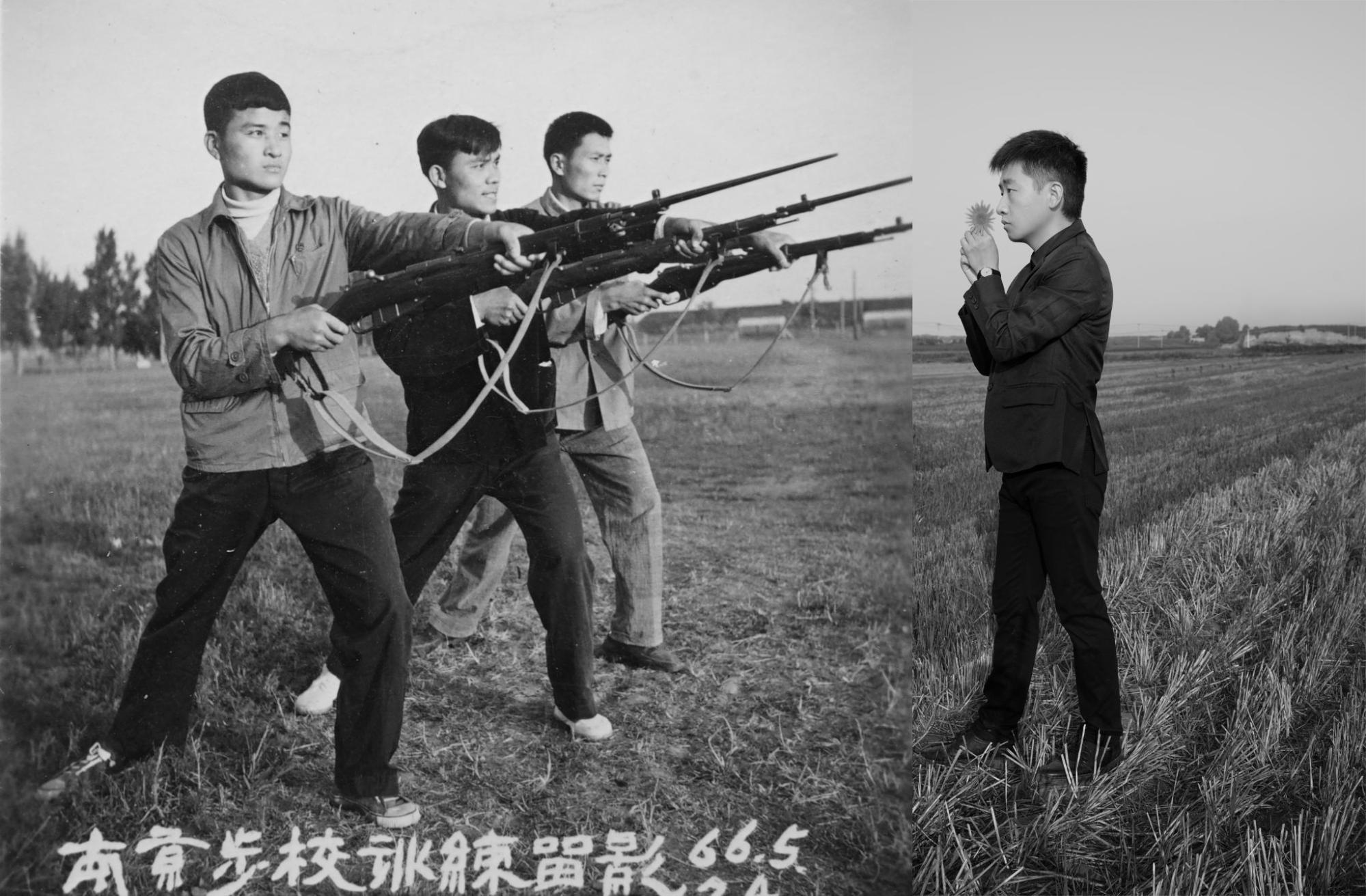

Once again, Shang looked for images of ordinary people, except that this time they appeared along communist slogans and Mao portraits. “I looked for photographs that capture history from the perspective of common people,” he says. “But these often feature individuals with firearms,” he notes. This stark contrast with the previous series highlights how easily a population can be dragged into manic revolutionary fervor.

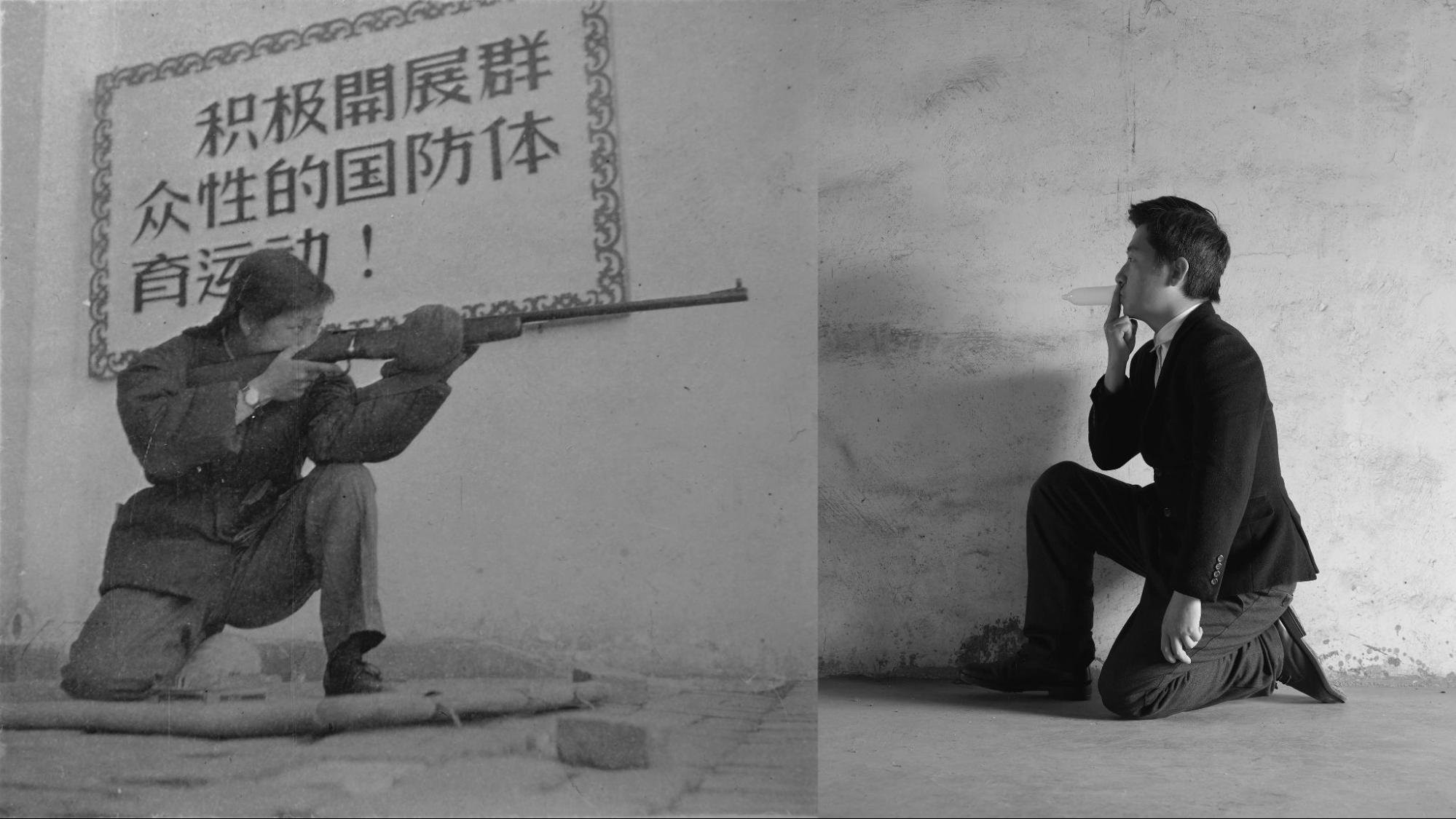

Mostly in black and white, My Time sees Shang juxtaposing the original photographs with re-creations featuring himself, always with a metaphor behind them. The composition Shoot the Condom, for instance, features a young woman posing with a shotgun in hand alongside a picture of Shang blowing up a condom in her direction. This piece is a social commentary on how China’s fixation with birth control went from encouraging large families during Mao to the brutal one-child policy and now to a concern that the declining number of babies will bring economic problems.

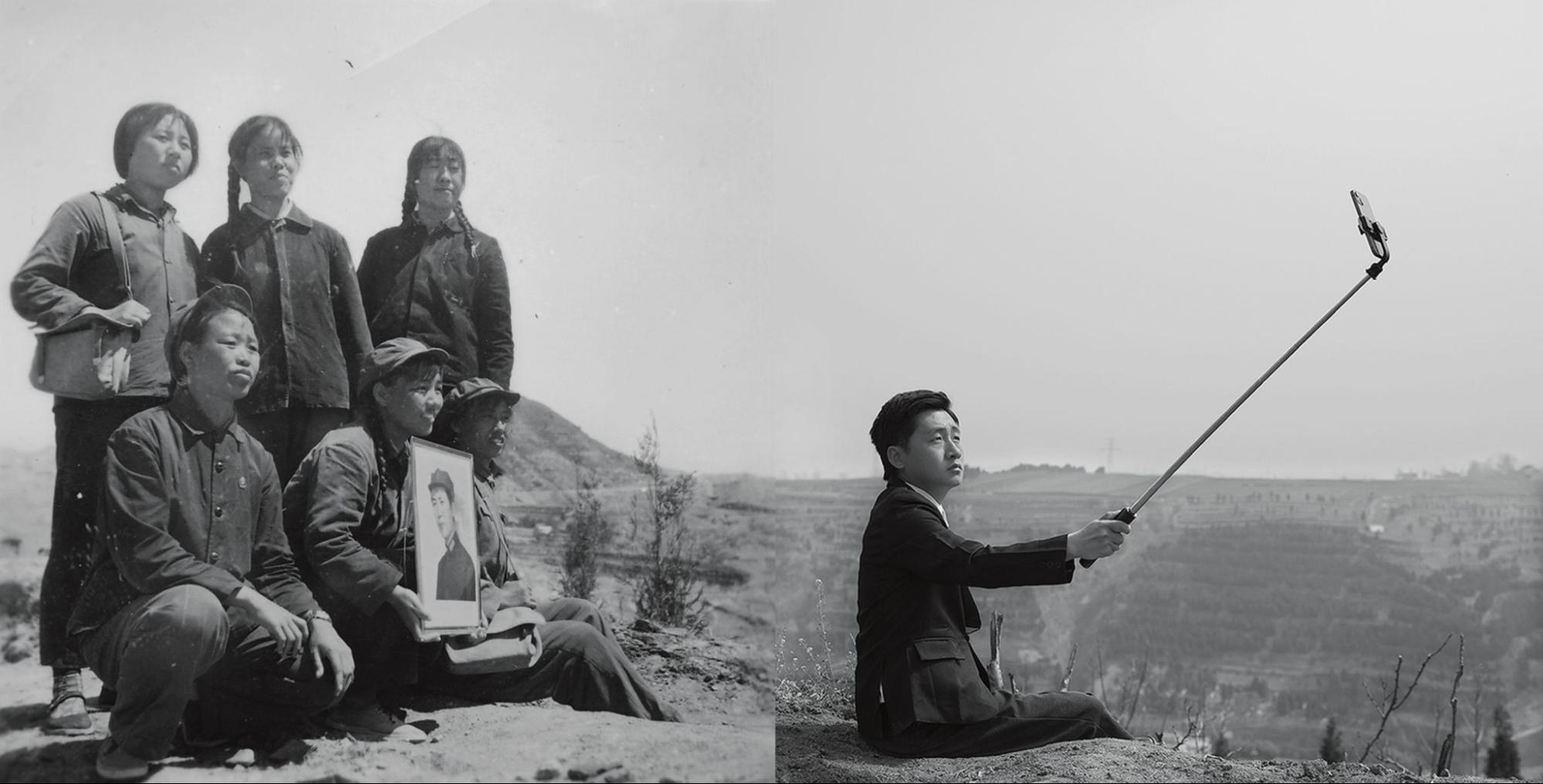

Several compositions also reflect the issue of personality cults. “The movement to create these god-like figures is of much benefit to authoritarian regimes,” Shang says. In iPhone Selfie, he combines a photo of a group of young women proudly posing with a portrait of Mao with one of himself holding a selfie stick. He carefully matched the background scenery of both shots to give the impression that he was the one capturing the moment with his iPhone. More tellingly, for Studying Ideology, Shang reenacted the scene of the woman reciting Mao that prompted him to start the series, except that he holds a book by Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and sits on a teacher’s desk underneath his profile.

In Red Veil, one of the few color, non-montage pieces in the series, Shang appears with a red cloth that flutters above his head and covers part of his face — notably his eyes. This piece relates to his feelings regarding his government and how it shapes people’s lives, a realization that dawned on him relatively recently. “I started learning more about China’s modern history on YouTube during the pandemic,” he reveals. “It was only then that I realized my upbringing was like a blank slate. It was as if I entered the production assembly line of the state machinery the very moment I was born.”

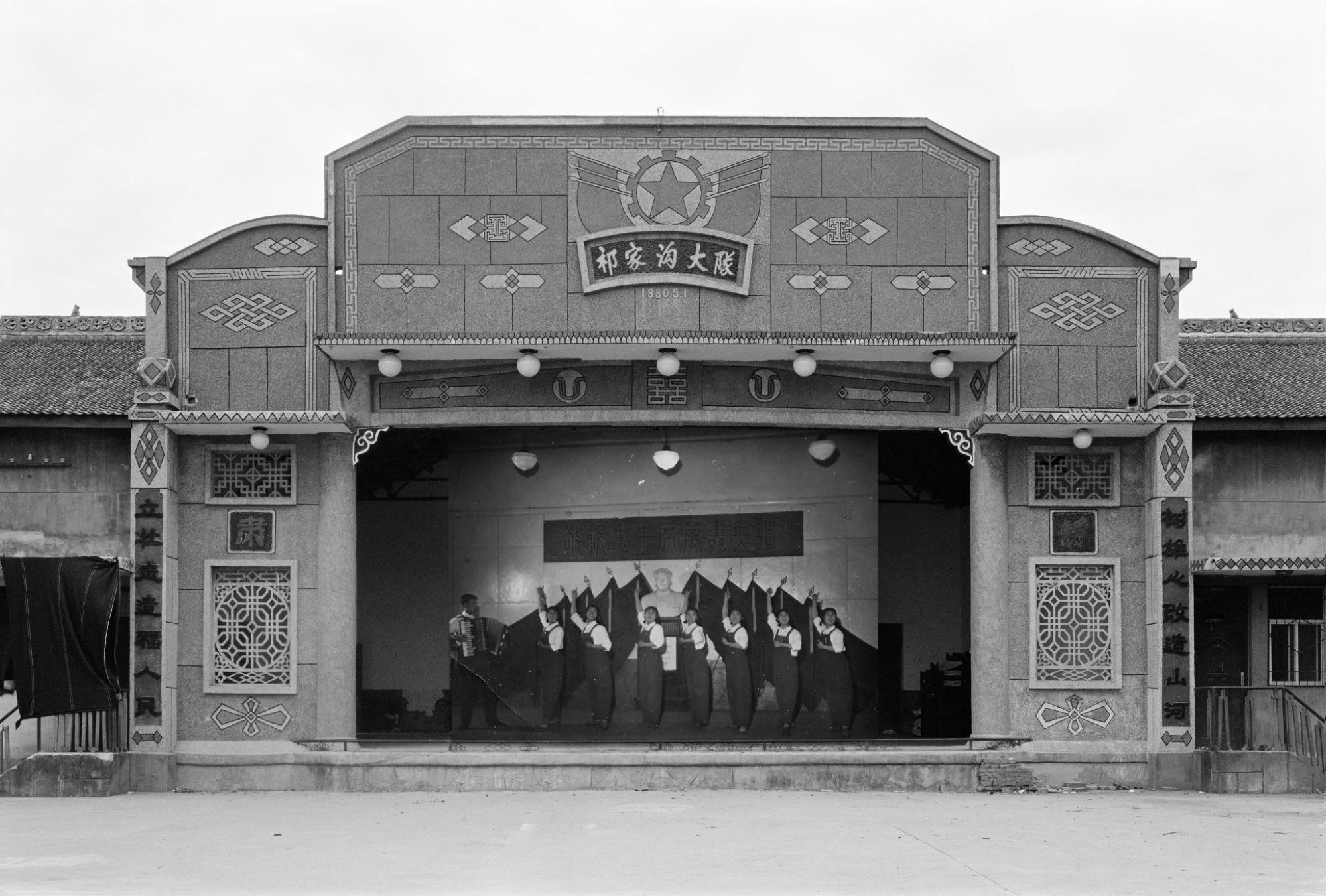

Shang’s latest series, Theater Stage, focuses on the way the state has shaped people’s minds through art and culture. He went on another field exploration and captured old open opera stages across Shaanxi. “The culture of opera stages in China has a history of several hundred years,” Shang says. Still, he notes that the ones he photographed are different. “They feature Chinese-style elements such as painted decorations and totems but also display red slogans and national emblems. These buildings are products of a specific period and hold immense historical value.”

Built between the 1950s and 1980s, the stages Shang portrays were meant for revolutionary model opera productions. The genre was institutionally popularized to transform people’s ideologies and values into something that matched the party’s needs. Shang presented two concepts for this series: “One focuses on the architecture itself while the other incorporates rare performance photos I added in post-edit. The latter approach does a better job in capturing their defining role for political propaganda during that historical period.”

It’s interesting to notice the different levels of decay the stages find themselves in. The vast majority are abandoned, but some have been converted into makeshift warehouses or workshops. One or two have been repurposed as senior care facilities or even themed restaurants. Only a few are occasionally used for performances, but now for traditional opera. “The number of these opera stages is steadily declining. While I was shooting this series, several of them were demolished, which is truly regrettable,” Shang says.

Like Shanghai Scenery, Theater Stage serves as a metaphor for the ever-changing social-political dynamics in China, and it does so by registering the impacts on the built environment through the interlock of time. When he inserts himself in his series with self-portraits, Shang emphasizes the notion that he and his generation are part of a narrative that is still unfolding.

It’s “like an incense that continues to burn, passed on from generation to generation,” he says. Such a sense of historical continuum, and how people dwell in it, is integral to Shang’s work. It gives it a touching quality that’s both epic and ordinary and that hundreds of millions of people on this planet can closely relate to.