This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

Cosmetic surgery is not for the faint of heart. No matter how you slice it, cutting people open to reshape their features is a gory business. Patients are wheeled home bandaged like mummies to start on a recovery that can take weeks. Once the swelling subsides and the scars fade, patients may well be happy with the results, but it’s a grim irony that a procedure to make you more beautiful can leave you looking — in the short term at least — like an extra in a slasher flick.

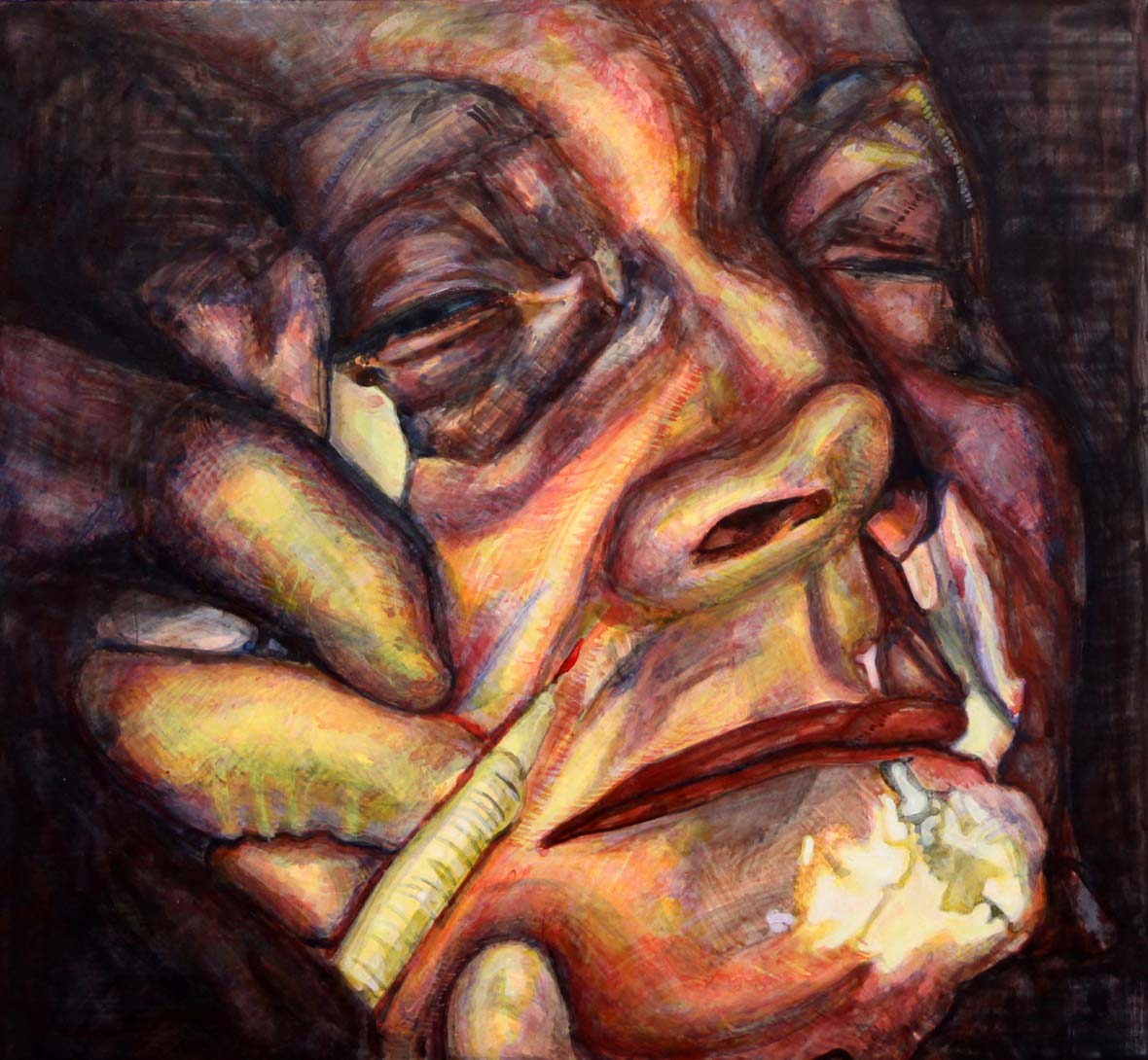

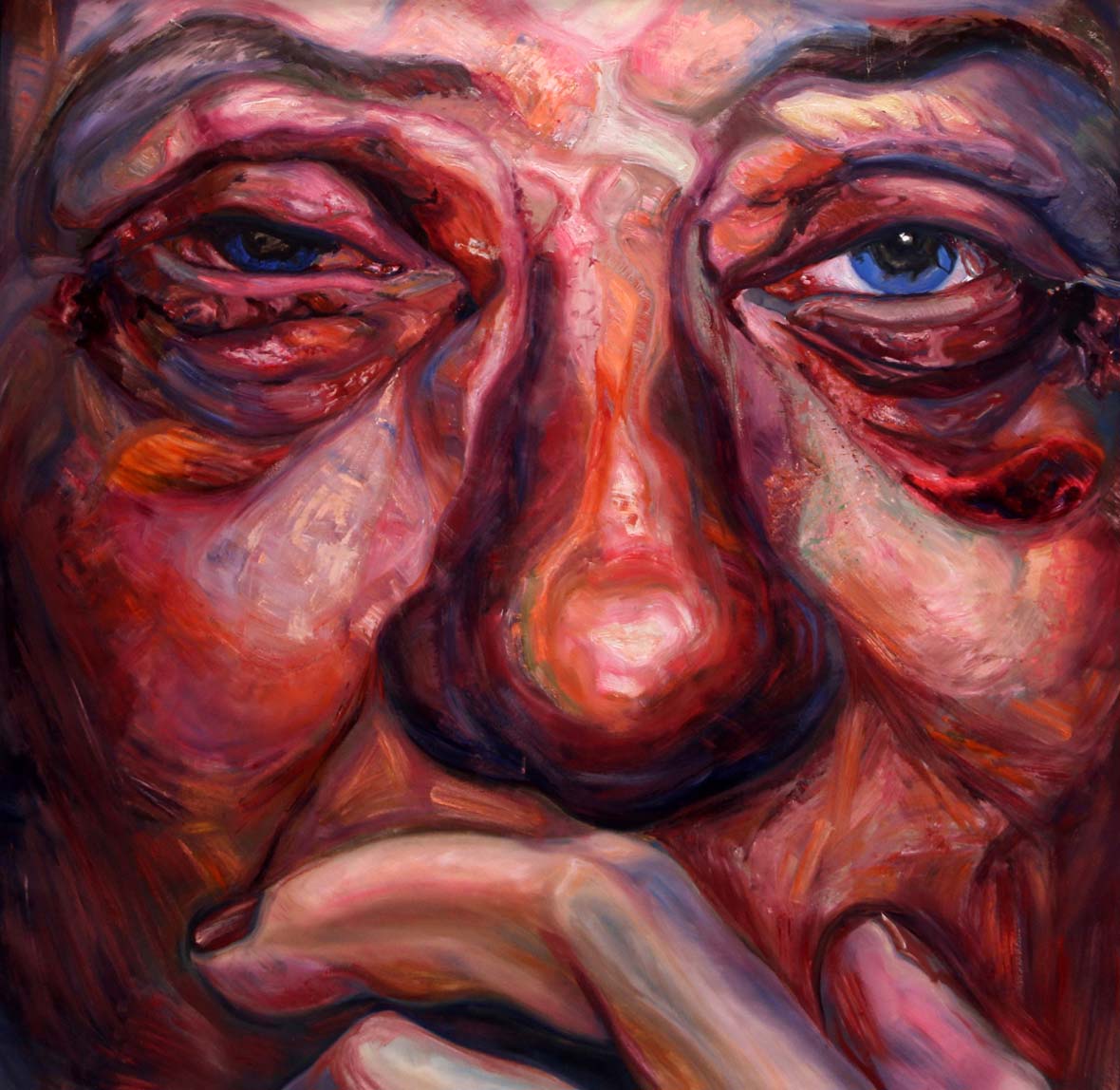

This awkward interim period, when patients have only just emerged from the operating chamber, is the starting point for the work of Sū Yáng 苏杨. Her work portrays in grisly detail the immediate effects of the pursuit of perfection: the bruises, the blood, the gauze, the swelling. She paints in oil and tempera, in garish reds and purples, and her works quite intentionally have something of a horror show about them. Yet the paintings are more than gross-out pics: Yang offers them as a critique of the beauty standards that lead women to submit to traumatizing procedures.

Yang is a scholar and artist from China. She learned to paint and draw from her father, who began instructing her in European techniques at a young age. In college, at Tsinghua University, she continued to paint, and also studied sculpture, lacquer, glass art, and graphic design. While doing a master’s in fine arts at the State University of New York at Buffalo, she discovered an interest in feminism, and since then her art has explored the procedures that women, particularly Chinese women, undergo to make their bodies conform to patriarchal ideas of beauty. She’s now working toward a Ph.D. in visual art at the University of Melbourne, where she uses her art and research to explore the demands women face in the name of beauty.

Are her paintings a condemnation of cosmetic surgery? For Yang, that’s not quite the point. “It’s more that my works emphasize the ideologies that encourage many young Chinese women to become the same single person, without their own features,” she says. In that sense, she views these beauty-enhancement procedures as a symptom of a larger problem: the pressure to conform to uniform, unrealistic standards.

In her academic work, Yang focuses on China, where cosmetic surgery is a booming industry. She notes that the pressures to look pretty are somewhat different in Australia and the U.S. “The notions of beauty are localized and formed by their own cultural and social histories,” she says. “However, I also see similarities in these standards, which are partly formed by a global consumer culture.” Her subjects are not limited to China but seem to show women of various ages and ethnicities.

She also doesn’t solely paint straightforward post-op portraits. Some of her works use cosmetic procedures as a starting point but take a more fantastic turn, with faces within faces, or people peeling off their skin.

Critiques of cosmetic surgery often poke fun at the dead eyes or frozen smiles of a procedure gone awry. Yang takes a different tack, showing a side of the cosmetic industry that’s seldom seen — the seamy underbelly, as it were, that’s surgically tucked out of sight. For many people, it seems, beauty is a bloody pursuit.

Website: suyangvisual.com

Contributor: Allen Young

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li