Pink Power: Sijia Ke unleashes her bubblegum universe

Pink-saturated and whimsically defiant, Ke’s art is all about girl power and reclaiming femininity.

The much-hyped, upcoming Hollywood release Barbie — directed by Greta Gerwig and starring Margot Robbie — has stirred a renewed obsession with “Barbiecore,” an aesthetic where hot pink reigns as the official color of happiness.

After a plunge in popularity that lasted at least a decade, the famous doll is regaining the spotlight. In the past, it has been critiqued for perpetuating materialism, unrealistic body ideals, and gender stereotypes, but there are those who never saw her in such a negative light. To them, Barbie’s bubblegum universe never actually died.

Shanghai-based artist Kē Sījiā 柯思嘉 belongs to this group. For years, she hid her interest in all things pink in order to fit in with “the cool crowd.” Today, at age 32, she sees art as an outlet to release the inner passions she suppressed during her teenage years: mostly garish pink stuff, luxury items, and a lot of vanity. She can finally say out loud, “I think I will still love Hello Kitty stickers and pink Maseratis until I’m 80 years old.”

Beyond the fantastic world of Barbie, Ke draws inspiration from anything girly she’s ever come across during her childhood. Her portfolio of sculptures and site-specific installations makes for a kaleidoscopic trip through a whimsical and glittery world replete with characters that marked her girlhood, from Hello Kitty and Sailor Moon to princesses and princes. Just as one expects from Barbie on the silver screen, Ke’s work highlights the importance of embracing one’s true self while demonstrating that a girly aesthetic is not incompatible with female empowerment.

Born in 1991 in Wuhan, Ke enjoyed creating art from an early age, and the motivation was purely selfish. “As a little girl, people always praised me for my drawing skills. So, to get more compliments, I started doing more and more art,” she says, laughing. “Gradually, it turned into a genuine passion.”

Ke’s vanity only grew with time, as did her love for a pink-dominated world. This is perhaps no shocker. She’s a true ’90s kid, growing up in a time when products marketed to children were largely divided by gender stereotypes. Entering a toy store, kids from Ke’s generation would find themselves surrounded by gender-based color coding and segregation: a broader spectrum for boys on train sets, toy guns, racing cars, action figures, and dinosaurs on one side and an onslaught of pinkness for girls on the other, with a much less diverse array of themes revolving mostly around surreal princesses or icy-haired dolls finding joy in performing domestic chores.

But as the 2000s unfolded, various organizations around the world called out toy manufacturers for assigning pink to girls and launched campaigns to urge for more gender-neutral toys. At the same time, youth subcultures were riding high in China, with trends such as streetwear, hip-hop, and skateboarding seen as the definition of being cool.

However, for Ke, there was something paradoxical in joining such subcultures. As she became a teen, she felt she had to curb her true self to fit in and conform with the non-conformists.

“It’s like carrying a backpack with many things you like from your childhood into your adolescence,” she says. “At first, you share what’s inside with others. Then, gradually, you tell others less about what’s inside your backpack. You then discover that youth should have a pattern, cool kids should like basketball and skateboarding. They should like trendy brands and music. You realize that what’s in your backpack is different from the definition of ‘cool’ and then you start to close your backpack and try to play the role of a cool kid like everyone else.”

To Ke, creating art was like slowly opening that backpack in a process of self-exploration and personal liberation. She spent more than a year trying to come to terms with the existence of such desires, but when she did so it was like an epiphany. “I discovered a powerful world, pure and rough, that carries layers of vanity in different forms,” she says. “Inside this world, there was a larger and more diverse version of myself. All this stuff is so superficial and vulgar, yet so precious and lovely.”

The experience was like “descending from her own world to the real world,” she adds. To capture the essence of how she felt, the artist created “Sijia Ke Descends to the World,” a three-meter-high inflatable installation of herself with wings as an ethereal fairy-butterfly creature who looks as if it just came out of a cocoon.

Ke says the meaning of the piece transcends her own experience. “This inflatable is not only an embodiment of myself but also a bridge that connects people and worlds. Each of us has a part of ourselves that belongs to this world of vanity and desire. Therefore, this is not only my image but also the manifestation of all fairies,” she says, adding that “these fairies can be anyone who enjoys the value of vanity and honestly accepts and loves the feeling of desire.”

In general, Ke’s creative concepts arise from impulses and mirror the way children create art. “Kitty With Flaws,” for instance, a pink clay piece decorated with resin jewelry, stemmed from her wish to make a small Hello Kitty accessory feel beautiful again. “I found this piece with a dent on Kitty’s face as if it were disfigured. I felt sorry for it and then gave it a pair of wings hoping it would be happy again and still feel like the most beautiful Kitty. Then I glued it to a very central position of a flower vase as if the vase were her stage. When you open the lid, you see a pair of beautiful shiny wings inside the vase, too.”

Ke’s collection of clay sculptures is made mostly of small vessels. But after decorating them with faux diamonds and gems, she prefers to see them as jewelry pieces. She also enjoys the sound of these hard plastic pieces rattling on their inside. These sculptures look like actual playthings, something you would find in a girl’s bedroom.

As a true believer of the idea that a girl’s bedroom is the embodiment of her entire universe, Ke collaborated with NeoBridge Hotel in Shanghai, turning one of the rooms into a space with pink lace curtains and frilly bedsheets.

“Everything is fake. In theory, everyone who checks in this room is a plastic princess,” says Ke, who was one of the artists invited by the hotel to conceive temporary rooms based on their signature style. Ke’s boudoir has two fake windows: One window looks out to Cinderella’s castle, and through the other, there is a prince standing by a white horse.

Not all of Ke’s work centers on passive femininity, though. There’s also a good dose of female empowerment, at least in one particular piece, which, once more, draws inspiration from childhood references, more precisely from the TV franchise that best combined fluffiness and feminine power in the 1990s: The Powerpuff Girls. “Three little girls who could fly and fight for justice? Every little kid in China wanted to be one of the main characters,” she says.

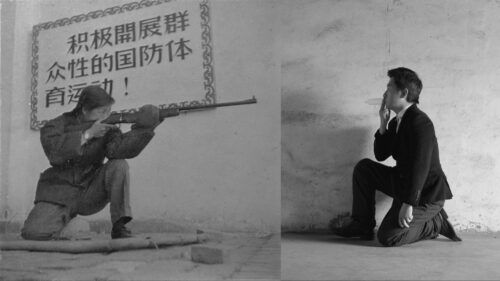

In her homonymous self-portrait series, Ke finds inspiration in the Chinese title of the franchise, fēitiān xiǎonǚjǐng飞天小女警, which translates to “Flying to the Sky Little Policewoman.” She juxtaposed pictures of herself as a policewoman and other signs of power and energy, such as fire flames, thunder, and metal chains with her usual, more adorable iconography, and then printed the result on large fabric kites. “When it’s spring and windy, I can fly. That’s how I became a Powerpuff Girl after 30,” she says.

In Ke’s world, empowerment and femininity are not mutually exclusive. Spiritually, she feels her work partially stems from the very concept of girl power. Meanwhile, from a purely aesthetic point of view, she enjoys the simplicity and authenticity that come with what some would see as “feminine stereotypes.”

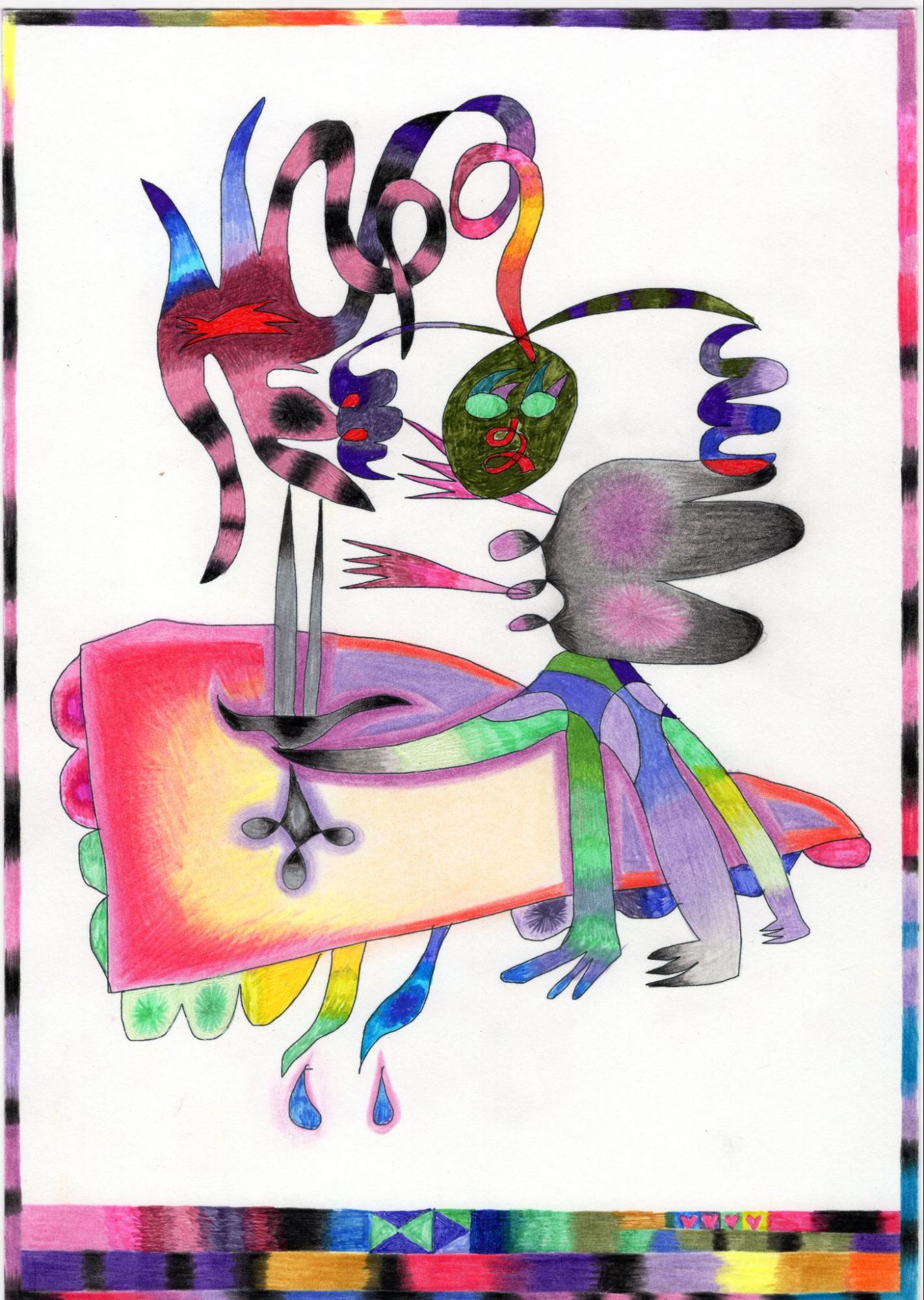

Ke thinks of her visual references as something childlike and pure. These days, she’s working on an ongoing series of pencil drawings that closely resemble the drawings of kids — both in imagination and technique.

Ultimately, Ke’s art tells the story of her turning that backpack upside down. It invites people to challenge and rethink existing concepts surrounding non-conformity, and encourages those with niche interests to live on their own terms.

In her work, there’s also a valuable lesson for girls, boys, and anyone in and outside the spectrum. Even though admittedly feminine in looks, Ke’s art is genderless. “I don’t think my work is marked by gender, but rather by personality and inner desire,” she says. “Crude desire is like a secret garden in many people’s personalities. Some are red, some are green. Mine is very pink.”