Shanhe University is the perfect Chinese college. Except it doesn’t exist.

How a made-up university in China became a viral meme — and revealed education inequality in the country.

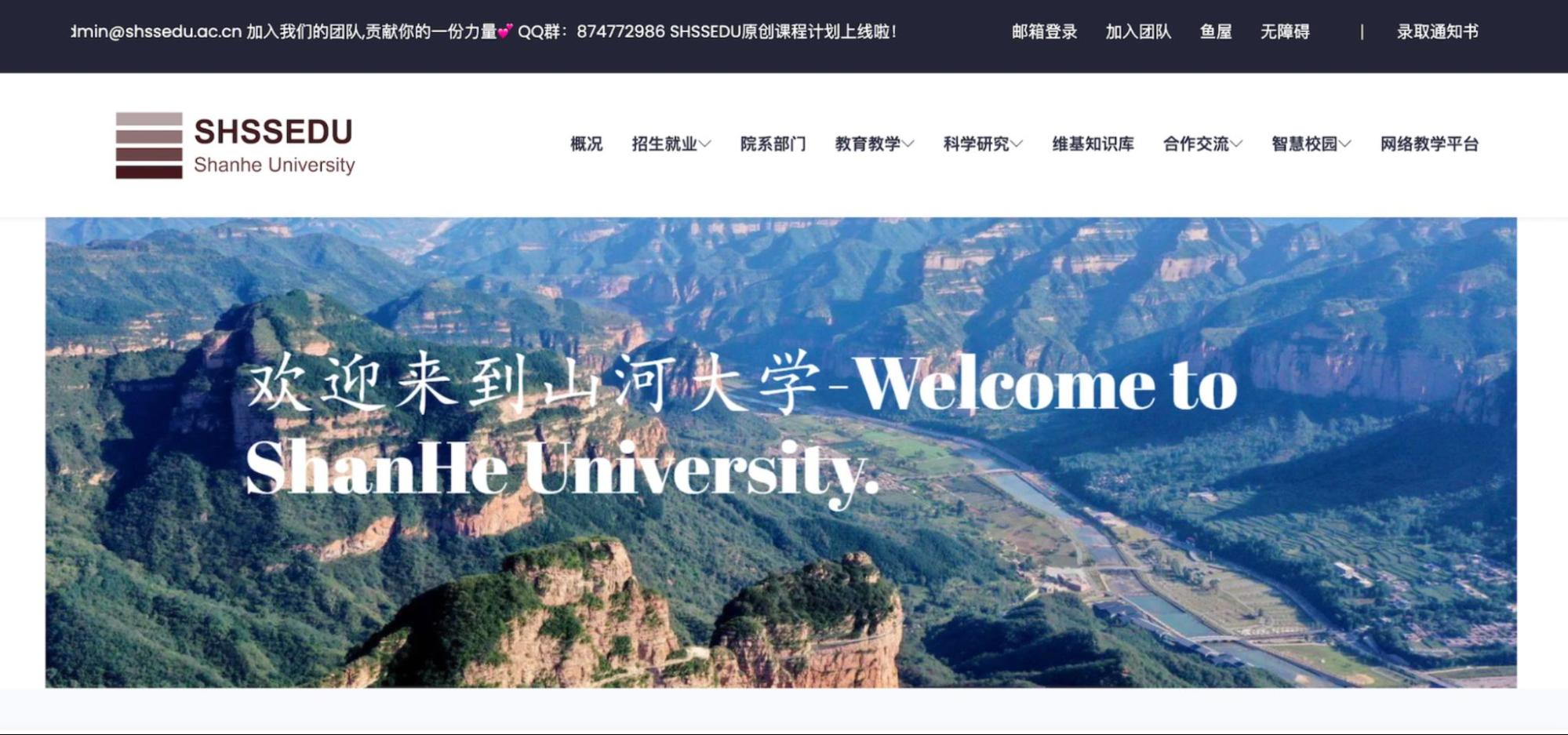

Normally, it takes decades — sometimes centuries — for a college to gain fame and build a reputation. But Shanhe University is an exception. Launched in early June, the institution has already emerged as the ultimate dream school for many students in China, with some showing off their acceptance letters on social media and envisioning a fulfilling college experience at the institution, which boasts an ultra-modern campus, an accomplished faculty, and a roster of well-designed programs, according to its website.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

It’s the perfect college in every way…except that it’s not real. And those who posted about it in the past few weeks aren’t delusional. “Everyone is in it for the joke,” said Xingheng, who asked to be referred to only by his first name. Having posted about the school as part of what he described as a “low-key social movement,” the 20-year-old college student from Shandong Province told The China Project, “Shanhe University is more than just a meme; it is a meme with a purpose.”

From a single comment to an online sensation

The origin of Shanhe University can be traced to a single comment that a Weibo user made in late June, after China’s 2023 national college entrance examination, commonly known as the gāokǎo 高考, concluded on June 9 and students began filling college applications based on their estimated scores.

While the process is nerve-racking for every college hopeful in the country, it’s especially difficult and stressful for those from the four provinces of Shandong, Shanxi, Henan, and Hebei, where the competition to get into decent universities is extremely cutthroat given their large populations of students and a disproportionately low number of prestigious institutions.

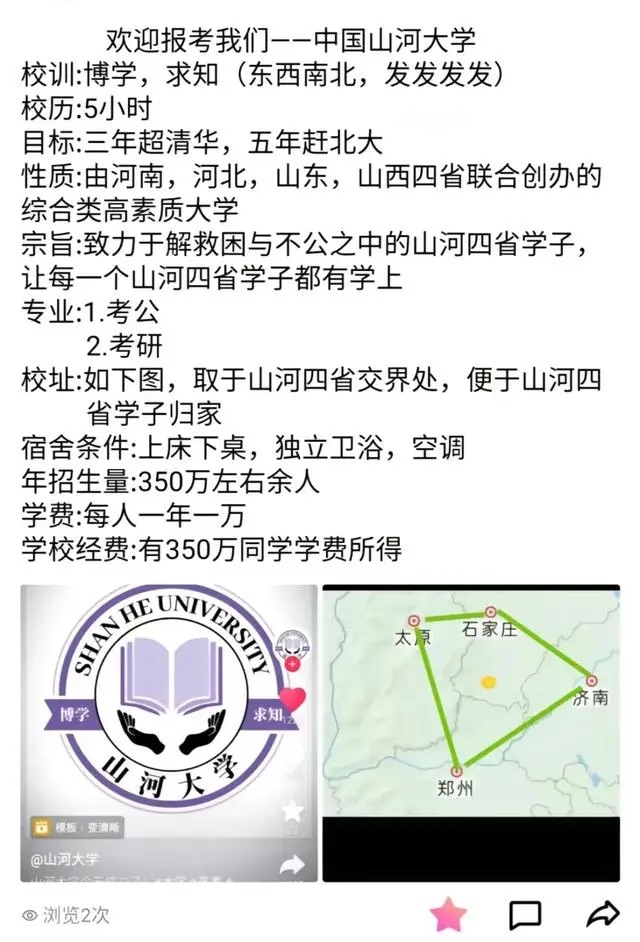

To increase opportunities for students from these regions, the Weibo user proposed the possibility of creating an esteemed university that serves them specifically. If each of the 3.5 million high school students who take the gaokao in these four provinces every year contributed 1,000 yuan ($140), the total funds raised would be enough to establish a comprehensive university that exclusively enrolls local students who are rejected by other schools, the person argued.

Basing its title on a portmanteau of the four provinces’ names, Shanhe University should be located at the intersection of these areas, the person added.

The idea may have started as a joke, but it took off quickly. In the following days, in what appeared to be a loosely organized online movement, a horde of internet users launched Shanhe University into viral meme status as they tested how far they could go to make it a tangible reality.

On the same day that the original joke was made, a recruitment poster for Shanhe University appeared on Weibo, stating that the school’s mission is to “rescue the students from the four provinces who are trapped in unfairness” and “allow each of them to receive a college education.” The college has “a total annual undergraduate enrollment of 3.5 million,” and its objective is to surpass both Tsinghua and Peking University — the top two universities in China — in five years, the poster reads.

Since then, an emblem for the school emerged, along with an architectural rendering of its campus, a design of its students’ cards, and the July menu at its cafeteria. Many proponents of Shanhe University said they would resurrect Dù Fǔ 杜甫, a prominent Henan-born poet of the Tang dynasty, as the principal, because his famous saying captured the essence of the school’s purpose: “I wish I could have a great mansion of a million rooms to harbor needy scholars in this world and put smiles on their faces.”

At one point, an official website for the university surfaced, with a deluge of fabricated acceptance letters from the school circulating online and a multitude of chat groups dedicated to various “programs” at the school being formed on social media apps. As a member of “Shanhe’s magic department” on WeChat, Xingheng said, “It felt like a large-scale role-playing game where everyone in the group was pretending to be a student at this totally made-up college. What we did mostly was just make silly jokes about our imaginary school life.”

As a Shandong native, Xingheng, who took the gaokao last year and is currently an engineering major at a local college, described the memeification of Shanhe University as a way to “protest a bitter situation with humor and imagination.” The dream of getting admitted into a prestigious university outside his home province has always felt out of reach, he said, adding that “the pessimistic feeling was shared by many of my peers.”

The myth of the gaokao being the greatest equalizer

The humor-charged discourse around Shanhe University “certainly reflects the long-standing dissatisfaction of students in the four provinces with the shortage of government designated universities,” Yong Zhao, an award-winning writer and a Foundation Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of Kansas, told The China Project.

In theory, education in China is broadly framed as meritocratic: If one works and studies hard, one will get ahead in school and life. In this way, the country’s education system has historically been considered an equalizer, a mechanism by which underprivileged students in the countryside get on equal footing with their richer counterparts in urban areas.

But the reality tells a different story. According to Sixth Tone, despite having a combined population of more than 300 million, the four provinces are home to only two of the 39 top-tier Chinese universities that are known as “Project 985” institutions, both located in Shandong. In comparison, Beijing and Shanghai have a total of 12 “985” universities, which make up a third of the 39 such universities across the country.

The disparity means that for students from the four provinces, they have to score significantly higher than their peers in wealthier cities when competing for limited enrollment spots allocated to their regions by elite universities. “China is a decentralized country in terms of certain things like education,” Scott Rozelle, a Stanford University professor who has studied Chinese education for three decades, told The China Project. He explained that because Chinese colleges receive funding from local governments, they in return allocate larger quotas to local students.

In 2022, less than 43% of the students who took the gaokao in Shandong Province were accepted into undergraduate programs, a figure that’s markedly lower than in metropolitan cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin. In the same year, Tsinghua and Peking University recruited a total of 300 students from Shandong, with an acceptance rate of 0.051%, which was one of the lowest in the country.

With 13 million participants, the 2023 gaokao cohort is China’s biggest yet. Nearly 10% of them are from Henan Province, where there’s no “985” university.

“On top of that — and perhaps even more important as a source of inequality — is the unequal opportunities for education and gaokao success between rural and urban children, even between those within the same province,” Terry Sicular, a Sinologist and economist with a focus on inequality and poverty at Canada’s Western University, told The China Project. “Such inequalities in educational opportunities translate into long-term inequality in incomes and life opportunities.”

Chinese education officials tried to reduce regional inequities in the past, but its attempts at reform were met with fierce pushback from those who preferred the status quo. In 2016, after the central government announced it would introduce a national scheme requiring universities in Jiangsu and Hubei Provinces to reduce nearly 80,000 places for local students and give them to those from poorer regions such as Henan and Guizhou, street protests erupted among parents who feared that their children would be negatively affected.

Similar to the demonstrations, memes about Shanhe University served as a chance for people to vent their frustrations over the gaokao, which has come under mounting scrutiny in recent years for its “inherent unfairness” after a major cheating scandal in 2020 and increasing debates about the urban-rural divide. “The gaokao does not really equalize anything in China. It is just one measure that people have been convinced to trust,” said Zhao from the University of Kansas, who provides an insider’s account of China’s educational system in his book Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon?.

The way Shanhe University evolved into an online sensation, according to Zhao, was unique in that it reflected “a Chinese way of expressing such dissatisfactions — no direct challenge to the government, kind of joking, and very unthreatening.”

The jokes were supposed to be lighthearted, but the collective displeasure behind them didn’t go unnoticed by the authorities. Earlier this month, as memes about the fictional school grew in popularity and entered the mainstream, spurring a barrage of opinion pieces by newspapers and leading students from other under-resourced regions to design their own versions of Shanhe University, Weibo censors blocked a handful of hashtags related to the school.

At a press conference on July 7, when asked about Shanhe University, Wú Yán 吴岩, the vice minister of China’s Ministry of Education, didn’t address the question directly. Instead, he stressed that the government would continue optimizing the distribution of educational resources across the country and prioritize central and western regions.

For Xingheng, although the movement was short-lived and didn’t result in anything substantial, he said it was fun while it lasted. “Whatever changes are made in the future, I won’t be able to benefit from them,” he said. “But maybe one day when looking back, people will think of these silly memes as a turning point in China’s educational reforms. I’d feel proud that I was part of it.”