This is book No. 29 on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“The book is much more than an artist’s impressions. He is most concerned with human beings. He is very candid; sometimes amused, occasionally shocked, by English ways and customs, but never unfair or unkind.”

—The Observer

“Mr. Chiang is a Chinese who has spent five years in this country. In The Silent Traveller in London he gives us his kindly comments on the people he meets and the things he sees, from the weather to after-dinner speeches. Mr. Chiang does not think much of our restaurants.”

—The Daily Telegraph

“Mr. Chiang Yee compares his book to ‘chop-suey,’ a Chinese dish of mixed up ingredients more highly esteemed here than in China. It may be that, but it is harmonised by a piquant sauce of näive humour and subtle observation.”

—The Guardian

“It has all the qualities of a good bedside book, because it contains the observations, comments and reflections of a highly cultivated man and gifted artist, on a great variety of topics.”

—The Ottawa Citizen

About the author:

Chiang Yee (Jiǎng Yí 蒋彝, 1903–1977) was born in Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province, to an artistic family. He married Tseng Yun (Zēng Yún 曾芸) in 1924, and the couple had four children. In 1925, he graduated from Nanjing University, taught chemistry in middle schools, lectured at universities, and worked on a newspaper in Hangzhou. He then served as magistrate in Jiangxi and Anhui. He became disillusioned with the Nationalist government and left for England in 1933 to study at the London School of Economics. He became a language teacher at London University’s School of Oriental Studies (now SOAS) and worked at the Wellcome Museum (now the Wellcome Trust). During this time, he started his artistic career and took on his famous alter ego of “The Silent Traveler,” writing and illustrating The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland (1936). This was followed by The Silent Traveller in London.

The Japanese attack on China and then the declaration of war between Britain and Germany made it impossible for Chiang to return to China — his sojourn became an exile. He became part of a (then) celebrated group of Chinese intellectuals — including the journalist Xiao Qian (born Xiāo Bǐngqián 蕭秉乾), the playwright Hsiung Shih-I (Xióng Shìyī 熊式一), the memoirist Dymia Hsiung (Cài Dàiméi 蔡岱梅), and the married poets “Shelley” Wáng Lǐxī 王禮錫 and Lù Jīngqīng 陸晶清 — living in Hampstead. Chiang wrote The Silent Traveller in Wartime and was himself rendered homeless during the Blitz, forcing him to move to Oxford (where a Blue Plaque commemorates the 15 years he spent in the city).

After the war, he continued to work on The Silent Traveller series, which came to include Oxford, Edinburgh, Dublin, Paris, New York, San Francisco, and Boston, concluding in 1972 with Japan. He also wrote a series of books for children featuring pandas, wrote guides to Chinese poetry and calligraphy, and illustrated many other books. He moved to the United States in 1955 and became emeritus professor of Chinese at Columbia and the Emerson Fellow in Poetry at Harvard. He returned to China in the 1970s, where he died in 1977 and is buried in his family’s tomb on Mount Lu, near Jiujiang.

The book in 150 words:

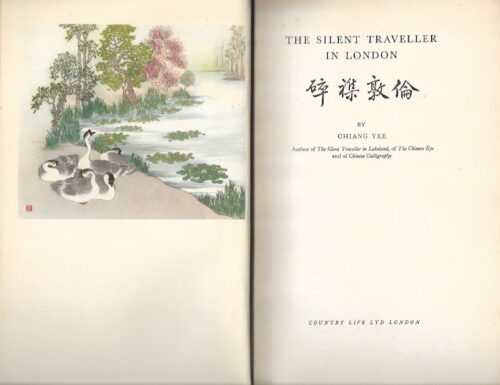

Chiang Yee’s The Silent Traveller in London was originally published by the books arm of the magazine Country Life in London. Second and third print runs were issued in 1938, and a fourth in 1940. The book is illustrated by the author with color and monochrome plates accompanied by his various observations, jokes, bon mots, and scraps of poetry in both Chinese and English.

Your free takeaways:

I am bound to look at things from a different angle, but I have never agreed with people who hold that the various nationalities differ greatly from each other. They may be different superficially, but they eat, drink, sleep, dress, and shelter themselves from the wind and rain in the same way.

In the London restaurant there is always a lively scene, and some places entertain the visitor with comedians and musicians, which I think is the most effective method of diverting the visitors’ attention from the taste of the food. Anyway, I think they (the cooks) are all good psychologists to keep the customer waiting until any food tastes good.

Regents’ Park is another place where I enjoy the springtime. The pigeons seem to flock there most of all. Sometimes an elderly man feeds them with peanuts; and sometimes a mother and her small girl. They light on your hands if you are not afraid of them, and they even take a rest on your head if you do not object. They are the friendliest birds.

Once I asked a young Chinese girl to write a short essay about London fog in Chinese after she had been here six weeks. She wrote that unlike many people who hated fog, she was very fond of it, because it was so mysterious and conveyed a sense of horror too.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Chiang Yee had, in his day, an enormous impact on Britain — his books, prints, illustrations, newspaper columns, and radio appearances on the BBC made him somewhere close to a household name and probably the best-known Chinese person in the country. The Silent Traveller in London was one of the first widely available books written by a Chinese author in English. Though Chiang Yee traveled widely in the British Isles, he lived and worked largely in London before the Second World War. It was a city he came to know well, embarking on long walks across the city from Hampstead Heath in the north to the West End, the Royal Parks, and into the working-class districts of East London.

As well as being about the city and people of Britain he knew best, this was a sad book for Chiang. No other Chinese writer of this time living overseas and writing about his experiences ever expressed the sense of homesickness and loneliness as explicitly as Chiang Yee. This is of course a familiar theme in much global travel writing, and here Chiang Yee reflects it through a Chinese lens. He was in London and did have friends, but was separated from his wife and children in China, and had not integrated into local life as much as his good friend, the playwright Hsiung Shih-I. Additionally, he was unable to return to his native Jiangxi due to the Japanese attack on China, around which time, as he notes in The Silent Traveller in London, his older brother and frequent correspondent suddenly died. Meanwhile, war clouds were gathering in Europe.

All of these factors combine to make The Silent Traveller in London perhaps the most poignant of the Silent Traveller series. Chiang is writing about a place he has come to appreciate and love — his fondness for ordinary Londoners and London life is obvious throughout. But he is a man divorced from his own culture, missing it dreadfully and constantly referencing it. Within a year, London would be at war with Germany; within two years, Chiang Yee would narrowly miss being sent home when a Luftwaffe bomb fell on his Hampstead flat (thankfully, his train back to London from Oxford was delayed!).

Next time:

One more Chinese writer who ventured overseas and wrote a book that has become a classic both in the Chinese world and in English translation. This time, a Taiwanese woman who traversed one of the most inhospitable regions of North Africa and wrote wonderfully about her travels.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.