China is known for its megacities, but 42% of it is wilderness — the barren and primitive, but also pockets of spectacular biodiversity. As the country’s adventurers discover the joy of exploring these places, they are challenging preconceived notions of China’s relationship with nature. They also bring the power to destroy or protect.

Mountain Water is The China Project’s newest monthly column, written by conservation photographer, writer, and filmmaker Kyle Obermann.

In the golden late fall of 2016, after giving up on my first, and last, corporate job, I ascended a 16,000-foot grassy hill just south of Yushu. No map, no trail, no rescue nearby; status quo for China. (I would learn that lesson well as I trekked the same region years later, followed by a pack of wolves.)

But on that luxurious autumn day, strolling through stubbed grass, dry tarns, and blooming Gentiana scabra scattered like purple stars across the yellow hills, I first glimpsed Ganggeqiaji. Hardly anyone outside of Yushu knew about it at the time, despite it being the tallest and most glaciated mountain in this reach of the Yangtze. Ganggeqiaji would change how I viewed China’s wild forever.

Wild China

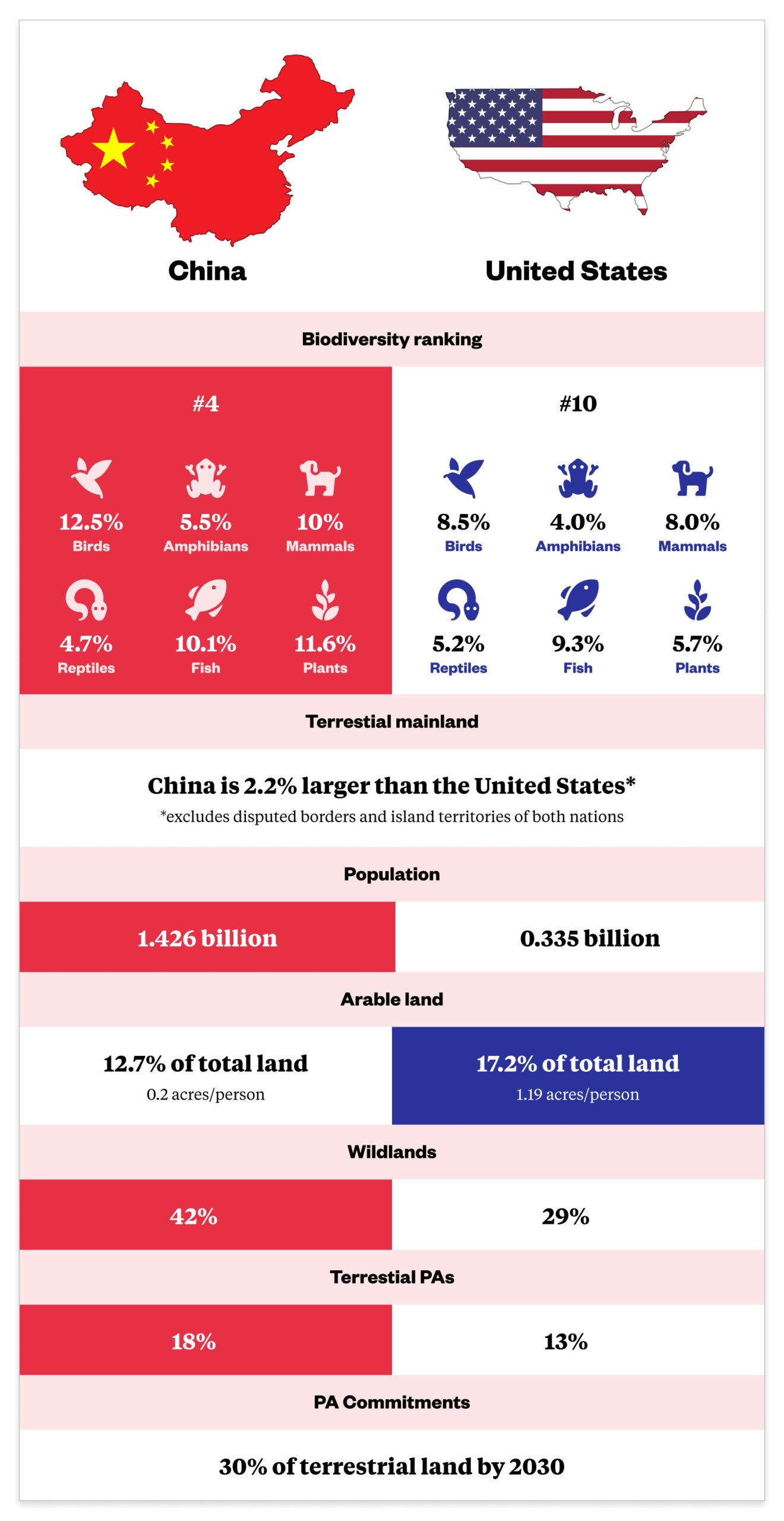

China is the world’s fourth most biodiverse nation. It has more large carnivore species than any country on earth, equivalent to that of the entire African continent. More people, too, but squeezed into only about a third of the land.

China’s mega-biodiversity is due to what Tibetan-Sichuanese writer Alai calls “the earth’s staircase,” the stunning transition from China’s eastern plains, basins, and low mountains to the Himalayan uplift, the roof of the world. Sipping tea near sea level in Chengdu on a clear day, if you gaze above the clouds 75 miles beyond the glittering skyscrapers, you can glimpse Yaomeifeng towering 20,000 feet above the entirety of eastern China. Go a little farther, and there’s Minya Konka (known in Chinese as Mt. Gonga) near 25,000 feet.

Where these peaks scrape the clouds and the earth buckles into ranks of mountains cut by roaring rivers is a biodiversity hotspot known as China’s Southwest Mountain zoogeographical subregion. It’s one of 19 total zoogeographical regions that define the nation’s landscape and biodiversity across tropical rain forest, cold desert, grassland, permafrost, and more. Within these regions hide patches of wilderness, areas of pro tected and unprotected water and land devoid of roads and human settlement. And while many living in China’s megacities fall into the trap of believing wilderness in China to be a misnomer, in 2019 a team based out of Tsinghua University published an incredible, eyebrow-raising statistic: 42% of China is wilderness.

“When we started our research, everyone was arguing whether China had wilderness or even if so how much it had. So this debate needed a scientific answer,” says Cao Yue, an assistant professor at Tsinghua University’s Department of Landscape Architecture and the lead author of the paper that contained the original study and statistic.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a Wilderness Area as “usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, protected and managed to preserve their natural condition.”

In many Western nations, the lines between believed civilization and imaginary wild have long been divided along park boundaries, puny native reservations, and private land. Wilderness etymologically means “the place of wild beasts,” leaving no space for humans in the minds of early explorers, conservationists, and land management officials.

This legacy fits IUCN’s definition best — a clear separation between anthropogenic nature and nature left alone. But, in China, much of the county’s identified wilderness overlaps with traditional use areas. Patches of undeveloped land that would identify via satellite as wildland are frequented by villagers for local resources or used by nomadic peoples across seasons.

Even areas often called pristine, like eastern Tibet, were heavily deforested by indigenous peoples for thousands of years to create south-slope-facing winter pastures for grazing yaks. Native Americans in Yosemite Valley similarly altered the land for agriculture, clearing conifers to create glades of black oaks for acorn harvesting. Vestiges of these oak-strewn meadows and cleared south slopes still exist today.

So wilderness’s definition is globally contentious, dependent on the span of time observed and perspective of the speaker. Given China’s mix of cultures and breadth of history, defining a Chinese version of wilderness that follows the rules is exceptionally difficult.

“The definition needs to be flexibly understood. I think what is most important is understanding a landscape’s distinctive features,” Cao argues. He points to the holy mountains and lakes in Tibetan culture that qualify as sacred natural sites under the IUCN, which now recognizes such sites as “the oldest form of protected areas.” These sacred sites, Cao says, though sometimes frequented by humans, also contain wilderness features.

Toward a greater appreciation of wilderness

Cao and his team are now translating the IUCN’s wilderness management guidelines into Chinese, which includes the value of traditional indigenous lifestyles and multiculturality into the value of wilderness. Their wilderness data of China is also being used by wildlife conservation researchers and national park planning officials to plan wildlife corridors for endangered species like the North Chinese leopard and new protected areas across the country.

The name Ganggeqiaji came off a scrap of flimsy paper written in Tibetan by a local nomad living at the mountain’s foot and confirmed after days researching at a local Tibetan library. It was the first documentation of the local name. Surprisingly, my photos of Ganggeqiaji’s lakes and glaciers published with Pengpai News were the first that the Chinese internet had ever seen. It opened wide the question that had been on my mind for years: Why didn’t more people, inside and outside the country, know just how wild China is?

The ignorance has two sources, according to Song Mingwei: culture and geography. Song is the former editor-in-chief of China’s largest outdoors magazine, Outdoor (户外探险 hùwài tànxiǎn), and the forthcoming author of the first book chronicling China’s alpine-style climbing history. “Forty years ago, people’s perception of western China was that it was an incredibly remote and even a dangerous place,” Song says.

They weren’t alone. In 1931, botanist Joseph Rock recounted to National Geographic Magazine traveling with trepidation to the now famous Yading Nature Reserve. Rock wrote: “Should any outsider now venture into Konka land he would be robbed and then slain.”

According to Song, if people wanted to go experience nature just after China’s reform and opening up, they looked east, toward the Five Great Mountains, the Four Sacred Mountains of Buddhism, and other famous traditional sites. Thoughts seldomly turned to the snow mountains out west that rarely, if ever, were mentioned in classic Chinese literature. Travelers went to Sichuan to visit the temples of Emei Shan, not to marvel at what Rock described as the “peerless pyramid” peaks of Yading.

The lack of infrastructure also proved an obstacle. In the 1980s, China had just begun construction of highways. Access to wilder places was either incredibly difficult or too close to home. In the 1990s, outdoor tourism churned to life, but mostly in the form of large groups traveling to famous eastern sites. Individual expeditions only started in the 2000s.

“Whether mountaineering or adventure sports, in the past 20 years, it’s come from a novelty into full swing,” Song says. Now, equipped with social media and cameras (phones), it’s those born after 1985 who are pushing China’s outdoor industry and wilderness exploration into a new era. As to whether this means they are in love with China’s wild or just following a social trend, Song remains doubtful.

“They just like to use these landscapes as an outlet, a psychological outlet. But the number of people who actually love these places hasn’t really increased much,” Song says.

“Shanshui” and the balance between humans and nature

Waiting hours for buses to ferry me and hundreds of other families, young couples, and retirees around Yosemite Valley’s famous scenic spots this summer, I wondered if there was really a big difference between Chinese nature tourists and American ones. Only on a 20-mile trail run in the high country was I able to evade the rénshānrénhǎi 人山人海 — an idiom referring to hordes of people, translated literally as people-mountain-people-sea — and pass solitary groups of backpackers finding their way, John Muir style. How many of these American tourists sought psychological outlet, and how many had come because they loved his place? China’s disconnect between people and wilderness, seeing the wild as a utility, not a love, may be more a product of our shared human nature than a special outdoors with Chinese characteristics.

“Essentially, wilderness is a state of mind. It is the feeling of being far removed from civilization, from those parts of the environment that man and his technology have modified and controlled,” writes Roderick Nash, a professor emeritus of UC Santa Barbara’s Environmental Studies Program, in his 1976 essay “The Value of Wilderness.” Wilderness, in other words, is in the eye of the beholder.

The most popular modern Chinese word for wilderness is huāngyě 荒野. It conveys a certain sense of barren desolation combined with primitive, even untamable, wild. The more appreciative phrase, yuánshǐ zìrán 原始自然, refers to original, untouched nature, and is often used in a more sentimental or scientific context. But the term shānshuǐ 山水, used throughout China’s ancient poetry and art, predates them all. Scholars who use it to study the roots of Chinese wilderness philosophy often come to a common conclusion: unlike early Protestant settlers’ manifest destiny in the U.S., full of heathenism and battles against savages within, the Chinese wild was traditionally viewed as a place for curious humans to retreat in solitude for psychological and spiritual well-being. There was no schism between individuals and nature, no need for humans to bend natural forces to their will.

“Chinese shanshui art obsessed with portraying huangye,” writes Chen Wangheng, a professor of philosophy at Wuhan University, in his 2020 article “The Wilderness Consciousness in Ancient Chinese Environmental Culture.” “But the huangye isn’t without people, it’s just that the human element isn’t dominant or flourishing.”

A new understanding of outdooring?

The 42% that Cao’s team measured may be free of visible human footprint, but China’s wild, as a state of mind for the elderly summiting Huashan or as a psychological retreat for millennials glamping post-COVID, is expanding in imagination, if not on paper as well. China’s protected 18% of its terrestrial land and is planning an additional 44 national parks to the first five it announced two years ago. But, according to Cao, 70% of China’s wilderness areas still lie outside nature reserves.

A few curious Chinese mountain enthusiasts initially questioned the new name Ganggeqiaji. Some Chinese maps had another name for the mountain — Baosuose — but the origin was unknown and the Mandarin name unrecognized by locals living nearby. Still, every year, some would add my WeChat looking for information about the route or photos of the peaks. During COVID, a group of climbers unsuccessfully attempted a first ascent of its highest peak. Then, this spring, Ganggeqiaji’s name appeared again publicly, printed and highlighted in yellow for the first time on a mountain map of western China. Seeing the Tibetan name printed there was an extraordinary moment.

In the last decade, Chinese people’s wilderness awareness has grown at a rate present-day state economic planners would envy. Once-obscure routes like the Minya Konka western circuit, featured in 2014’s TV series Extreme Treks exploring “the most remote regions on the planet,” are now introductory routes for trekking novices. The start of the trek is anything but remote, reachable within a four-hour drive from Chengdu.

Unfortunately, the wild’s growing popularity has also threatened it. Trash abounds. But a little-known, fascinating case revolving around western Sichuan’s popular Eye of Ge’nyen alpine tarn hints at coming change.

In the summer of 2021, to help facilitate a growing number of visitors, the local government began construction on a raised walkway around the tarn’s perimeter. But, when China’s outdoors community found out, fears that the construction would hurt the tarn’s surrounding fragile alpine environment drove immediate online criticism and pushback. Drone photographers were among the most vocal, protesting that the new walkway would ruin the classic aerial angle the tarn’s symmetry provided. One day after the online protest began, the local government released a statement canceling the project, promising to remove the section already built and restore the grassland.

Chinese government officials reversing the seemingly irresistible pull to develop the wild hardly seems common. But could it be? Guests in Yellowstone were encouraged to feed bears for 100 years before the National Park Service reversed course and brought the practice to an end in 1970. As Chinese people — and the rest of the world — become aware of China’s other half, the fate of one of the world’s wildest countries balances on an edge. Which way will it tip?

When travelers get curious about exploring China’s wild, I only have one suggestion. Leave the English and the expats behind. There are a few exceptions like the Itinerant Climbers Collective and TrekHaba.com, but the list of English sources with reliable instructions is woefully short. Instead, search for inspiration from the Chinese: on mafengwo.cn and Xiaohongshu while cross-checking and downloading routes on 2bulu.com. For objectives with no prior existing information, I planned the Ganggeqiaji circumambulation with Google Earth. And, of course, leave no trace.