This Week in China’s History: August 23, 1884

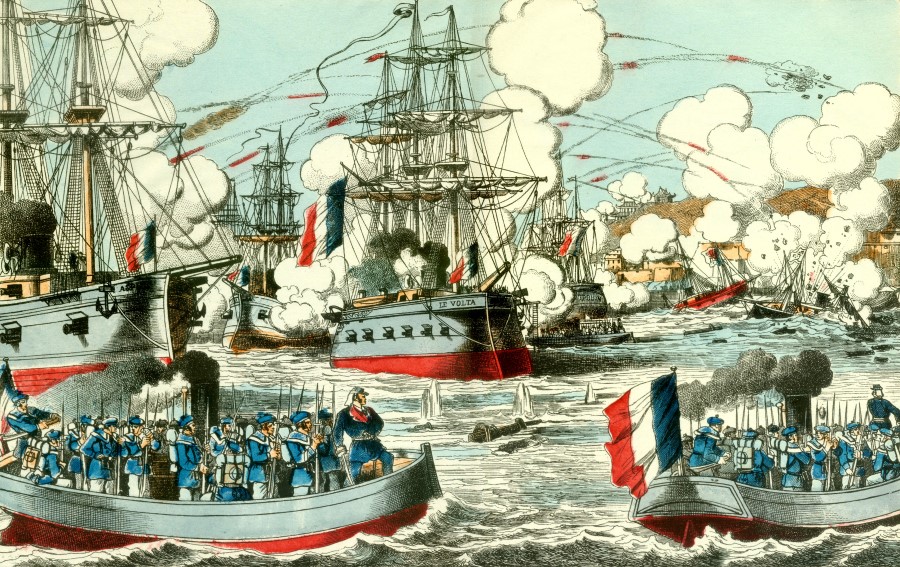

On August 23, 1884, a French fleet steamed into the mouth of the Min River, near the port of Fuzhou. Although tensions between France and the Qing empire were high, the French sailed without incident past the Chinese coastal defenses and approached the Qing empire’s most advanced fleet, docked at its most important shipyard. War, though not yet declared, was very much the French intention, and they had caught their quarry by surprise.

Eleven of China’s newest warships were docked at Fuzhou’s Mawei port, and the French set upon them before they could weigh anchor. Torpedo boats began the assault, and 10-inch guns completed it. In historian Bruce Elleman’s summary, “within the space of less than one hour, naval bombardments destroyed not only the cream of China’s southern fleet but also the Fuzhou shipyard…approximately three thousand Chinese were killed, and damage to ships and docks were estimated at USD 15 million.” Nine of the 11 Qing ships were sunk.

The Sino-French War of 1884–85 was inconclusive. It was hard for either side to claim victory; more plausibly, both sides lost. But the Qing debacle in Fuzhou was undeniable: For decades, the Qing policy of “self-strengthening” had promised to master and adapt foreign technologies. The Fuzhou Naval Yard was one of the policy’s crown jewels. Now both the shipyard and the policy were in ruin.

One of the most persistent myths about 19th-century imperialism in Asia is how China and Japan responded to it. It is “conventional wisdom” that Japan embraced Western technological superiority quickly and was thus able to rapidly modernize, becoming itself an imperial power within just a few decades. China, on the other hand, neither understood nor accepted new technologies, and its refusal to change cemented its decline, leading to the “century of humiliation” that included it being carved up among a half-dozen powers while its last dynasty collapsed and civil war engulfed the country.

To be sure, China and Japan fared differently in the late 1800s, but assigning this to the two countries’ attitudes toward imported technology is, at the very least, misleading. The destruction of the Qing fleet in Fuzhou — framed as the “southern disaster” — came to be seen as a prime example of Chinese incompetence and inability to modernize.

But, predictably, there is more to this story than meets the eye.

Fuzhou was not only one of China’s most important ports — an obvious choice for inclusion as one of the ports opened by treaty after the 1839–42 Opium War. Although trade at Fuzhou may have fallen short of expectations (especially in contrast to its northern neighbor Shanghai), the port became the site of one of China’s most advanced shipyards.

The Fuzhou Navy Yard had been started in 1866, the brainchild of Qing general and official Zuǒ Zōngtáng 左宗棠. Zuo had been approached earlier by two French friends, Prosper Giquel and Paul d’Aiguebelle, about partnering on a shipyard in Tianjin. While Zuo demurred on this first project, he sought out the Frenchman to help develop another one in Fuzhou. In two decades, it had become one of the Qing empire’s most important military and industrial installations, with an ambitious plan to produce an entire flotilla — 19 state-of-the-art warships — by 1875. The sprawling facility encompassed more than 40 buildings across 114 acres, employing some 3,000 people at its peak. In his pathbreaking article on the topic, historian Benjamin Elman describes the yard as “probably the leading industrial venture in late Qing China.”

Despite all this, the workshop was not without its limitations. As historian Hsien-ch’ung Wang described, the yard’s initial contract called for the construction of ships that were just one-fourth as powerful as the current state-of-the-art in Europe — 150 horsepower compared with 750 — and furthermore planned for ships built with wood and iron plating: a decades-old technology that in Europe was being phased out in favor of iron-hulled (and soon steel) vessels.

This notwithstanding, the Fuzhou Navy Yard was producing the most advanced ships in Asia. Even after the debacle of 1884, the shipyard would rebuild and advance to the point that it was producing steel-hulled ships, with advanced propulsion systems, launching five such vessels in 1889.

Moreover, Qing China had more than 50 modern warships at its disposal in 1884 — more than half of which were built in China — making it by far the largest and most advanced fleet in the continent.

Why, then, the conventional wisdom that Qing China was unable (or unwilling) to modernize while its neighbor, Japan, was?

Part of the answer can be found in the events of 1884.

In Elman’s summary, officials in Fuzhou “requested assistance on numerous occasions from the northern fleet,” but the powerful Qing official Lǐ Hóngzhāng 李鴻章 refused to send help. In addition, ships from the Guangzhou fleet made it clear that “Canton was not in the war — this being simply a local dispute — they held completely aloof from us.” Elman’s diagnosis: “Regional loyalties, a focus on provincial defense rather than national defense, and political distrust among the different naval fleets” led to the French attack being successful.

The war itself, on the other hand, proved inconclusive. In fact, after the Sino-French War, China’s reputation increased: Whereas the Opium War of 1842 had demonstrated a clear technological gap between Chinese and European arms, 40 years later, the distance was much diminished. And the ships in Fuzhou were not the only ones at the Qing’s disposal. There were four fleets — besides Fuzhou, they were based in Shandong, Shanghai, and Guangdong — all of which had their own regional sponsors and constituents. The northern Beiyang fleet — based in Shandong and sponsored by Viceroy Li — was particularly formidable. Yet the four fleets did not see common cause in one another.

When war came again, against Japan in 1894, most observers expected the Qing navy to easily defeat its smaller neighbor. When it didn’t — to the contrary, the Qing forces were routed on land and sea — a new explanation emerged, suggesting that the Chinese were poorly equipped and poorly trained, with little support or interest in fighting. In actuality, as Elman demonstrates, the 1895 defeat was much more down to the same internal divisions that were present in 1884, as well as corruption and political infighting that led, famously, to Qing shells being loaded with sand or cannon being filled with cement.

But the explanation that China was unable to modernize lingered for many decades — to a large extent it still dominates, with the period of 1865 to 1895 framed as one of technological failure and ideological reaction. In this version, the story of the Sino-French War was retold: Rather than a stalemate born of Qing advances, French treachery, and Chinese internal division, war was now seen as a Qing defeat that was the result of Qing backwardness. Everything becomes part of a predictable downward spiral leading toward the Qing’s inevitable demise.

Theories of inevitable decline are almost always wrong. Historians are, rightly, allergic to “inevitable” explanations. There is little to learn from the lesson that the Qing was doomed all along. A fuller understanding of the Qing decline shows how political disunity can hamstring development, and how inability to put the greater good over individual interest could lead to mammoth consequences. And, don’t forget that sneak attacks do happen.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.